Podcast: 22 minutes. Listen Now, or Download to Your Favorite App for Later, by clicking on “Listen in Podcast App” above right.

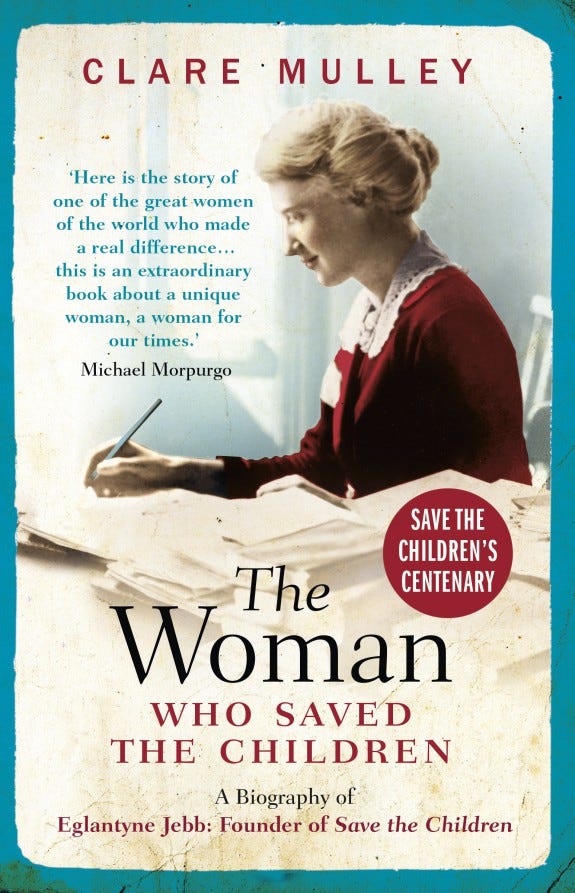

A few days ago, I had a great video chat with Clare Mulley, and here it is for your mobile listening pleasure as an audio podcast! Clare is the bestselling author of critically acclaimed biographies The Spy Who Loved, The Women Who Flew for Hitler, and, our subject today, her first book, The Woman Who Saved the Children.

Eglantyne Jebb was an upper-middle class Victorian Englishwoman, but she was also a pioneering modern: She was among the second generation of young British women to go to university, she engaged in groundbreaking social science research, and, above all, she founded a charity that was ambitious and international from the beginning.

My chat with Clare is also available in transcript (at the end of this page) and as a video, which is in this post:

I introduce The Woman Who Saved the Children in my longform retelling of Clare’s story in Annette Tells Tales, which you might (or might not!) wish to read first (spoilers!). This post and the interview aim to thoroughly whet your appetite for this book, and all of Clare’s biographies:

TRANSCRIPT

I’ve lightly edited this for clarity. Annette

ANNETTE LAING: I'm Annette Laing. I write Non-Boring History on Substack. I'm delighted to have with me today Clare Mulley, all the way from the UK. Clare is an award-winning, bestselling author, writing meticulously researched historical biographies.

Among her books is The Spy Who Loved, which is about Krystyna Skarbek, otherwise known as Christine Granville, a Polish noblewoman who was reputedly Churchill's favorite spy during World War Two, and who really out-Bonded James Bond.

She's also written The Women who Flew for Hitler, about two women who flew airplanes during WWII for the Nazis, but ended up having two very different stances on the War. Clare is also a book reviewer for various august publications in the United Kingdom, including The Spectator, The Telegraph, and History Today. She's also familiar to British viewers for her frequent appearances on television, including BBC's Rise of the Nazis, Channel 5's Secret History of World War Two, and Adolf and Eva. All of her books, so far, are optioned for television and movies. These are all books with Incredible popular appeal that also complicate our understanding of her subjects. But the book I'm going to discuss with Clare today is her very first, and it's on quite a different subject. It is The Woman Who Saved the Children and this is story of Eglantyne Jebb who, as the title suggests, founded the charity Save the Children

Clare, by the way, holds a master's degree from the University of London, in social and cultural history. But unlike most of the authors that I write about and talk about at Non-Boring History, Clare wisely did not go into academia, which gives her a really terrific opportunity to connect with the public in very, very thoughtful ways. Welcome, Clare. Thank you for taking the time from your very busy schedule. I do appreciate it.

Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children, upper-class Victorian woman, very much a woman of her times, and she founds this charity. And yet she's very blunt about it: She didn't like children. You are a very modern person and the mother of three. What led you to write about her?

CLARE MULLEY: Yeah, I love this seeming contradiction. I don't think it actually is a contradiction. But it is true that she'd been a teacher early on in her career and she really found children very stressful, exhausting, too loud, noisy. And yeah, I've got three. But she kind of respected them. You said she was a woman of her times. I think perhaps she was ahead of her times in many ways. So she saw children as human beings. I think she said the idea of closer acquaintance [with children] appalled her, and it was a dreadful idea, so she didn't beat any bones about it. In fact, in the year she set up Save The Children, she told her best mate, her very close friend Margaret Keynes, that, she said, it's appalling I have to give all these talks about Save The Children and, you know, the common love of humanity towards children. It disgusts me. So she really didn't particularly want to spend time around children. She wasn't particularly maternal herself. She didn't have any children of her own. She never, in fact, married.

There could be a number of reasons for that. But I do think she respected children. What she saw was young adults. She saw people, at a time when most people didn't think that children actually were humans enough to have human rights. Human rights were only for people of the age of 18, and below that, there were parental rights, and the state had rights over children as well, but children didn't have individual rights.

So one of the things that she did was she pioneered the idea of children being human beings, and being party to human rights.

ANNETTE LAING: I noticed she laid the groundwork for the the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child.

CLARE MULLEY: There's a wonderful story about that. Apparently, there was a sunny summer Sunday. [In] 1924, she climbed up Mont Salève. And in fact, I went out to Mont Salève. I was actually pregnant at the time, doing my research for this. And I went out and I thought, well, I'll climb up as well. This was my third child. So I'd had two. And I'd been watching The Sound of Music, and I thought these mountains might be, you know, filled with daisies in the fields, but, no, it's sheer, vertical rock for thousands of feet. It's incredible. And so I went up in a sort of ski lift that takes you up to the top, and it had black and white photographs in it of ladies in cloches, but it turned out that had only been put in place a couple of years after Eglantyne died. So she actually did go in her long skirts and tightly laced boots and climb up this mountain. She settled down at the top, and looked down over Geneva, which of course, is the international city. The lake of Geneva at that point was full of barges with building materials to build what is now the United Nations building, which was then the League of Nations. It's where Esperanto was formed, and the International Women's League was there. So she settled down and cracked a square of chocolate. One of the many things I take from her is my love of chocolate. And she looked out over this view, and she was inspired to come up with this idea that every child, everywhere in the world, should be party to the same universal, human rights, and she penned a statement. It was just five things, quite basic, initially, about healthcare, food, education, a safe space to play. All those sorts of things. And she marched down the mountain and got it pushed through the United Nations, the League of Nations as it was then. She was actually the first adviser for women and health care to the League of Nations.

ANNETTE LAING: She was a very practical person. And one of the things that came out in the book, is that it is experience that pushes her to work for children, as opposed to with them. What were her pivotal experiences or influences that drew her into this work?

CLARE MULLEY: She had already had . . . I don't want to go into cod psychology. You can go back to her childhood and the death of her younger brother, which affected her very deeply. She refers to him a lot later on in her life. I think he's this sort of representative of the potential abuse of the value of life. Another commitment she took at that point was to live a life of social purpose. And she was inspired by her parents. Her mother set up a national organization in the creative industries, to give people artisanal skills, and so on. So she had a wonderful example of a compassionate idea being turned into a national movement, through her mother's work. She was one of the second generation of women in Britain to get a university education and she went to Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford, which now has a bronze bust of her in their library.

And so there are a number of inspirations. But of course, it was the First World War. Just before the war, she went out [to the Balkans] for her brother-in-law. She was very close to her sister Dorothy, who had married a Liberal MP, a Quaker. And he went out to the Balkans and saw what was really, we now know, the rumblings towards the First World War. But then, it was sort of seen as a civil conflict in that part of Europe. He sent out [Eglantyne] because she'd already done good work in charities in Cambridge. But she had never really considered doing international development work, or help. So she went out and set up soup kitchens, and family tracing, and things like that. She realized then that this is really important work, but it's ambulance work, relief work, and what you need to do is try and stop some of this from happening [in the first place]. So she's taking a very progressive view, even very early on. Then she came back [to England], and her work is completely swept aside by the First World War which is very depressing.

But [during WWI] she takes an active role, translating the [European newspapers] with her sister Dorothy. Eventually, at the end of the war, she's really appalled, because the British then-Liberal government decided to continue the economic blockade against Europe as a means of pushing through harsh peace terms, or really to get better reparations for Britain. Eglantyne felt if people knew the human cost of that policy, they'd be as appalled as she was. Because, at this point, there were about 800 children dying in Germany every week.

ANNETTE LAING It's interesting that she had this sort of early grasp of the power of propaganda. So that during the First World War, she and Dorothy, and others, Dorothy's husband, were working to translate the foreign press, articles showing a very different perspective on World War One, which really walked a fine line, didn't it, in terms of legality? Because the British government had strict censorship, but you know what? They're showing that maybe the news you're getting isn't the news. And then after the war when she, when she was arrested for distributing pamphlets . . .

CLARE MULLEY: Exactly. You have this wonderful leaflet. She had become part of the planning council to try and change that legislation. That was getting nowhere fast. You said she was practical. She was.

She gets up and produces this leaflet with a very upsetting photograph of what looks like a little baby, can't stand, massive head, tiny body, but it's actually a two and a half year old girl who's suffering from malnutrition and whose body hasn't developed sufficiently because the nutrients are needed for the brain. [Eglantyne] started taking that around, distributing it, mainly in Trafalgar Square, the sort of traditional site of public protest in the center of London, where the suffragettes often were, and she was using suffragette tactics.

So she was chalking up the pavement, saying, "Fight the Famine, End the Blockade". And she was, of course, arrested pretty much immediately. Well, she managed to get rid of eight hundred leaflets, but she was arrested and taken away. But they made a bit of a mistake. She's not the sort of person that you can quietly sweep under a carpet.

So, when her court case came up, she actually insisted on presenting her own defense. And she knew that, legally, she didn't have a leg to stand on, because her leaflets weren't cleared by the government censors. So she focused on the moral argument, and she gave the court reporters up in the gallery at the courthouse plenty to fill their columns with.

The crown prosecutor, Sir Archibald Bodkin, he didn't spare her in his condemnation. But once the case was closed, she was only fined five pounds, and it could have been five pounds for every leaflet, or she could've been given a prison sentence, you know, so it really was the minimum. Once the case was over, he came up to her, in front of everyone, including the reporters, and took out his wallet a five-pound note, you know, they were quite big in those days, and pressed it into her hands. You know, it's the sum of her fine. He's clearly saying, as far as I'm concerned, you know, morally you won your case. And she said, no thanks. I can pay my own fine. But she took his five pounds. She said, I'll put this towards a new cause, to help save the children of Europe. And that was the first donation ever to Save the Children, from the crown prosecutor at the founder's arrest.

ANNETTE LAING : Lovely, lovely story. And, you know, what you said earlier. that she was a woman ahead of her time, I do think you bring that out in the book that Save the Children rapidly becomes, not just a local little charity in London, coming out of this one little group. She meets the Pope! There are branches of Save The Children all over the world, in pretty short order.

CLARE MULLEY: That comes from meeting the Pope, yes. She actually wrote first to the head of the Church of England, who was Archbishop Randall Davidson at the time. And because she was a Christian . . . Her faith was kind of unique and spiritual, but it was within the Christian fold, in her mind.

And so she wrote to the head of the Church of England, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for support. And he thought, well, actually, this is quite political, wasn't she arrested? You know, he didn't even bother writing back.

So she just wrote to the Pope, and he was much more interested, and invited her to meet him. So she went over to the Vatican. She had to wear a mantilla over her face, and then the door burst open, and an emissary called out in Italian.

She spoke many languages, but, sadly, not Italian, but he kind of turned and ran on his heels. She said he looked like an Indian rubber ball in a purple dressing gown, kind of bounding down this corridor. And she's holding onto her mantilla, and pulls up her skirt, and pegs after him.

And she went into this big hall. It was full of gold and big pillars, and there, she said, was a little figure at the back, standing still like a ghost, and suddenly remembering, you know, Popes tend to wear white, look a bit ghostly. She bobbed down on one knee, and it was the Pope, and he came and raised her up.

And instead of the 20 minute appointment, he gave her over two hours, making notes in what she called a grubby little notebook. And he was so inspired by her. I mean, she commissioned some very early research, but her passion as well, her knowledge [came across]

He said, I won't just ask Catholic churches in England, as she had requested, to give their collections one day for Save the Children's cause, but I'll ask Catholic churches around the world.

And because of that, these individual congregations overseas then said the need hasn't gone away, and they became the early Save the Children overseas.

So, you have this very interesting and very modern organization, that not only raises funds in Britain and sends it overseas, but raises funds all over the world, and sends it wherever it's needed.

Reciprocity like that is at the heart of what [Eglantyne] believed. So for example, one of the first donors to the children of Vienna after the First World War were the mining unions in Wales. They came together and all their members put some money in to help these children who were starving to death in Austria, in Vienna. And then about four, five years later, there was terrible poverty in the Welsh valleys, because there were miners' strikes, and a collapse of the industry. And there was real suffering among the children. And the City of Vienna got together and raised funds, and sent aid and, you know, funding support back over to Wales.

That's how it's always been. It's not about you know, what we now call the developed world, or the Western Hemisphere or the North helping the South or whatever. It's about wherever there is need and wherever there is opportunity to help, it's reciprocal.

ANNETTE LAING: Right, she had, in that way, a very modern perspective, very egalitarian perspective. And yet, you know, at the same time, when I think of her as, here's this woman with this incredible upper-middle class confidence that is sort of developed, particularly, I imagine, at Oxford. And so, you know, in that sense, a Victorian woman who has such a short life, dies at 52.

You know, the world of nonprofits, as we say in the US, or charities today, is a very different place from in Eglantyne Jebb's time. Would there be a place for an Eglantyne Jebb in the world of nonprofits or charities today?

CLARE MULLEY: There are some, and we need more, there's no question of it. Yeah, and she was very ahead of her time. It wasn't just that. I mean she was the first person to use cinema photography, cinema footage, to really bring home to people what was going on. She used, you know, "skip lunch" for the first time, donate your lunch money. She did all of these things. Sponsor a child was part of that initial team. So was fundraising use of branding, it's absolutely fantastic. You see her wearing Save the Children hats. I've looked everywhere in people's attics for that hat. If you come across it , Annette, please let me know.

ANNETTE LAING: I will, I will!

CLARE MULLEY: She using all these very modern ways, and her language we're talking about, it's not patronizing, it's very modern. And so, yes, of course, we need much more people, you know, working along those lines.

And, you know, there's other things that she brings as well. So, I mean, her closest relationship in life was with a woman, and for a long time, this wasn't talked about because people are worried, you know, about the sensitivities around that. Thank goodness, a lot of the world has moved on now, and this is something discussed much more openly. In fact, Save the Children does a huge amount of work around LGBTQ+ issues, which is fantastic. So how wonderful to have a woman like that who was pioneering the way, back in the day.

ANNETTE LAING: Fantastic. And you did yourself work for Save the Children when you began this project, which brought you into contact [not literally— A.] with Eglantyne Jebb. And all the royalties, I believe, from this book go to Save the Children, which is fabulous and marvelous.

So from your first project, then, to your most recent. You're writing a book, I believe already under contract with Weidenfeld and Nicholson, called Agent Zo. So can you give us a little preview what that's going to be about?

CLARE MULLEY: Lovely question, thank you. Agent Zo's the working title. Hope it'll be called that, we'll see, and it's about this incredible [woman] in the Second World War. She's basically a special agent in the Second World War, and she was the only Polish woman to manage to bring contact between their commander-in-chief in occupied Poland, the first of the occupied countries. She gets through Germany, through France, over the Pyrenees, this extraordinary journey, and being shot at in the mountains and all the rest of it. [She] eventually reaches London, where she reported to the Polish commander-in-chief, Władysław Sikorski and had to go through working with SOE [British intelligence during WWII]. And then she's there, and the Poles are just amazed that a woman has achieved this. Some of them say, can't we just kiss your hand, you're a goddess to us, I mean, how did you manage it? You're so wonderful. And she's just like, oh, stop all that lip. Where are the files? Why aren't you answering the ciphers quickly enough? She tries to improve all their systems, and they can't stand it because she's a woman. So one of them tries flirting with her. He thinks, oh, maybe, if I talk about silk stockings, that'll, you know, get the feminine side out. She's just like, oh, come on.

So she's just sort of given all these extra hurdles, and in the end they say, okay. thanks. We've got all the information. She brings this incredible stash of information about persecution of the Jews, about some of the V1 missiles, the Vengeance, you know, that's the buzz bomb, troop movements, everything. They go, okay, thank you. That's been fantastic, Zo. Now, where do you want to relax? Do you want to spend the rest of the war in Scotland? She said, don't be ridiculous. I'm going back to Poland. And they're like, well, how? You know, you can't parachute. And she said, why not? The men are parachuting.

So she becomes the only female member of the Polish Special Forces, paratroopers, the Cichociemni, or Silent Unseen, to parachute back behind enemy lines into Warsaw, and then fights in the Warsaw Uprising. And that's not the end of her story.

I mean, she's just this amazing, amazing woman.

ANNETTE LAING I detect this theme in your books, being drawn to these to these exceptional, extraordinary women. Or maybe they're not exceptional. I mean, that's the other thing. I often talk to teachers, and one of the things I chide everybody about is, don't assume you know everything about a subject. Just don't, you never will, and much of it still remains to be written. Most of it still remains to be written. There are just so many stories. And right now, and this is just my own personal comment that you need not endorse, we have just seen a very concerning uptick in misogyny in the last couple of years, this thing about Karens that I find very, very strange. It is so good to see you complicating people's understanding of women's role in the past.

CLARE MULLEY: A gray area.

ANNETTE LAING: Yeah, and you're dealing with stories that academic historians, and I think it's fair to say in Britain particularly . . . It's a more conservative field. They're going to attack me for this, but it is a more narrow field, and you've been able not only to do work that they haven't, but also to bring it to this enormous audience. So for that, thank you so much, Clare Mulley.

Once again folks, you can get this and any of Clare's wonderful books from the source of your choice. And of course, I do encourage folks, to, you know, avoid the dreaded Amazon if you can, but either way, do get ahold of Clare's books. Don't forget libraries and independent bookstores. Clare, it's been an absolute pleasure having you today. Thank you so much for your time.

CLARE MULLEY: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

Clare Mulley’s The Woman Who Saved the Children is available from libraries and booksellers.

Share this post