Out of One, Many Marys Again

ANNETTE TELLS TALES Born into Slavery, Raised in Wealth. Meet Mary Church Terrell, because you'll be glad you did

Note from Annette

This is my 500th post at Non-Boring History, so I’m making this one free. When you’re a Nonnie, an annual or monthly subscriber, you get searchable access to all 500 posts, plus every post from now on.

I don’t normally follow the various historical recognition months and days on the calendar when I write about history, for excellent reasons. But today, I feel like giving an encore to a post that blows readers minds, and yes, it fits with Black History Month in the US (In the UK, February is LGBTQI+ month, while Black History Month is in October.)

This is a good moment to mention that Black History Month is not all about slavery and racism, which is what too many Americans think Black history is: Things done to black people. Instead, BHM stresses what historians call agency, that is, black Americans actively doing throughout American history.

Today is about Mary Church Terrell, and if your response is to say “I’ve never heard of her, and so don’t care” or “I’ve heard of her, but I’m not sure I care,” then, hey! This is what NBH is for! The point isn’t to know who Mary Church Terrell was for the sake of knowing, or to win a pub trivia contest (although that’s cool). The point is for me to try to interest you in an astonishing life story that shows so many roads taken—and not taken— in America.

History done right is not for the sake of the past. It’s to provide context—complicated context from a complicated past- for us, living in a complicated present. For our own sakes.

Onward.

This post first appeared at Non-Boring History March 4, 2023. I’ve made a few minor edits for clarity.

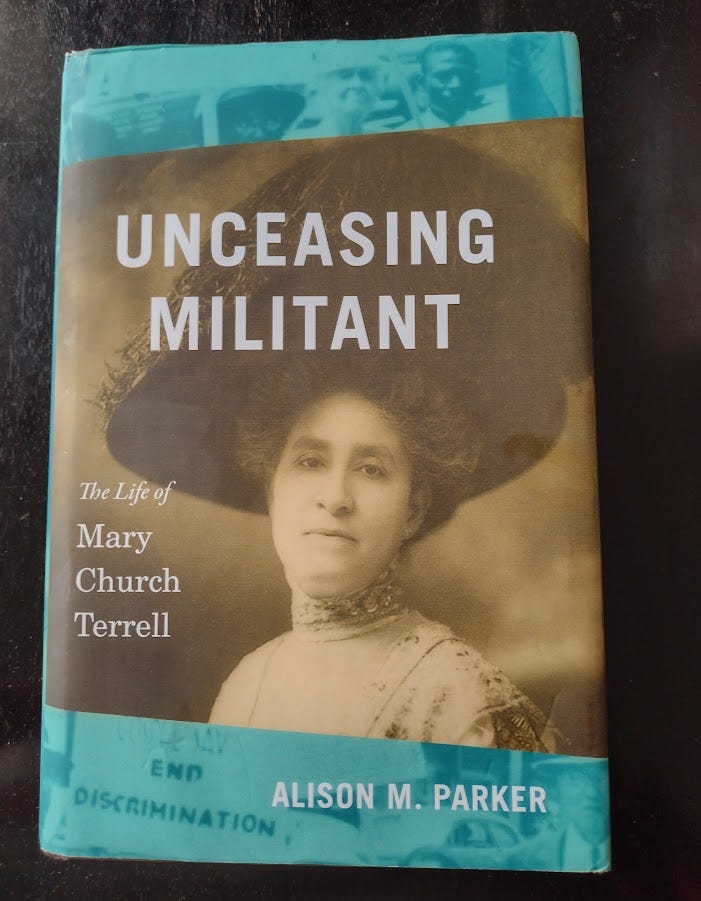

Today, I'm riffing on Unceasing Militant, the totally brilliant biography of Mary Church Terrell by historian Dr. Alison M. Parker of the University of Delaware.

A Family Story

I lived in the Deep South for 23 years. You read that right. Some white Southern families reminisced fondly about how their families “treated slaves kindly”, and considered them “part of the family”.

Blimey. Where to even start with that? I mean to say . . . I could point out to them that people aren't pets, I guess? That family legends are seldom critical? Or I could chain them to chairs and make them listen to my lecture about actual families in slavery. But I would get arrested for the “chaining them to chairs" thingy. So maybe I’ll just give you my response, and ask that you relay it if you get a chance, like if Great-Aunt Virginia visits from Charleston?

And I’ll respond with a story, starting with a family story, my riff on one told by historian Alison M. Parker of the University of Delaware. I’m trying to make it as easy to follow as I can.

Let’s start with the birth of a slave in Memphis, Tennessee. Mary was the child of enslaved parents, Louisa and Robert. Both Louisa and Robert were the children of enslaved mothers and white slaveowners.

Mary’s great-grandmother, Robert's grandmother, was named Lucy. Lucy lived in slavery in Virginia. Lucy’s master/rapist sold her, and their child Emmeline, who would one day be Robert’s mother, and baby Mary's grandmother. That’s a lot of genealogy to swallow at once, and I won’t judge if you need to read it again. Take it in. Gasp. Yeah. I know, right?

Lucy and Emmeline’s new owner, Dr. Patrick Phillip Burton, later gave Emmeline as a “gift” to his own daughter, to serve both as playmate and maid.

When the doctor ran into debt, he sold Lucy to the Deep South, to Mississippi, separating her forever from young Emmeline. The cruelty by these men is truly stunning: Selling children, including their own children, away from their mothers,

Decades later, baby Mary, all grown up, learned the story from her father, Robert, who, in turn, had learned the story in a letter from Dr. Patrick Phillip Burton’s white family. The white Burtons seemed oblivious to the impact of this horrifying story on Robert and his family. They were only concerned with putting a cheerful spin on their patriarch, Patrick Phillip Burton.

By the time they wrote their letter, sickly sweet yet horrifyingly poisonous, Mary was free, comfortably off, and a mother herself. She was aghast, but also fascinated. She was already fighting a war of words with white Southerners about “kind” slaveowners, making speeches and writing articles pointing to the overwhelming evidence of the brutal truth of slavery. This fantasy, the kind the Burtons indulged in, the myth of the kind slaveowner was still very much a thing in 1901.

A thing in 1901? Oh, heck. Look, white people were still talking of '“kind slaveowners” when I arrived in Georgia in the 1990s. I was gobsmacked. I challenged a woman, a teacher, who reeled off this twaddle to me at a party. She fled, thanking me for my “opinion”. It’s not a bloody opinion, I tried to say. It’s facts. But she was gone. I wouldn't be surprised if she was still trumpeting it today, because she wouldn't be alone.

Historian Alison M. Parker tells us in Unceasing Militant that Dr. Patrick Phillip Burton’s white slave-owning acquaintances thought he was a vicious bastard, which is really saying something. Burton often challenged white men to duels. He physically assaulted a white neighbor, and an elderly white minister, beating them both savagely. Huh. Hmm. Well, he sounds nice and kind, doesn't he?

NBH GNOMES’ SARCASM ALERT: The Gnomes of Non-Boring House remind readers that Dr. Laing is British, and can’t help herself.

And that’s what Burton did to white people, so what he did to the people he enslaved doesn’t bear thinking about. But if we’re genuinely interested in history, we should think about it. Nobody who reads real history about slavery can miss that violence and slave ownership went hand in hand. And the violence didn't end in 1865.

Mary was born into slavery two years before the end of the American Civil War. By 1901, to repeat, she was very much free. And she had a lot to say.

She repeated the story of the cruelties perpetrated on her own family, and others’. At a time when racism was at its height, worse, even, than in the time of slavery, she would not be silenced.

She realized that it spoke volumes that even her family, the most “privileged” people imaginable within slavery, light-skinned house servants, the children of their masters, skilled, best able after slavery to launch into freedom, had still suffered such terrible pain.

In rejecting the absurd fantasy of happy slaves living contentedly as one big family headed by nice posh white men with excellent manners, Mollie spoke up not just for herself, but for millions.

Yeah, how could people have believed that self-serving crap about kindly slave owners, you might ask? Let’s see . . . Ever watch Gone With the Wind? One college student of mine in Georgia, years ago, kept talking about the crinoline dresses in the movie, and how she would have loved to have lived then, and I couldn't shift her, no matter what I argued. And anyway, all of us think self-serving crap about something. How can we tell what to believe in the age when we’re bombarded with information, including facts wrenched from context, and outright lies? That's the great challenge of our times.

People listened to Mary in her times because, despite her unpromising start in life, she became a privileged, confident, and well-known woman of integrity, the wife of a lawyer in Washington, DC. She was a leader in numerous organizations, and she didn’t pursue anything just for the money. But, get this, she still had to be paid something, because she needed money to keep doing what she did.

Mary was a graduate of Oberlin College, a fancy college in Ohio. She had studied in Europe. She had taught Latin. She spoke both French and German fluently. She had a wider and deeper understanding of the world than the vast majority of Americans, no matter who they were. And yet she never stopped having to deal not only with sexism, with the assumption that a woman couldn’t know what she was talking about, but with the racism that was becoming worse through much of her adult life.

Speaking of things getting worse, here’s a little more on Mary’s family history: After posh doctor/slaveowner Patrick Burton wrenched away Lucy from her daughter Emmeline, Mary’s grandmother, he handed Emmeline over to his white, slave-owning friend as a sexual plaything. That’s why Mary’s father, Robert, like her grandmother, was also conceived in rape. And like the whole family, he, too, was enslaved, by his own father.

Mary's family story would now take an altogether unexpected turn. But first, get your breath back, and follow me forward to the mid-20th century, to meet Mollie.

An Unusual Partnership In A New Age

It’s Washington D.C. , and World War II has been over for quite a while now. Annie and Mollie have become friends. They make an unlikely pair of civil rights activists, but everyone agrees they are one heck of a team.

Annie is a modern woman, energetic, swears a lot, but she’s not a person you hand a megaphone to, and not just because of the swearing. She prefers to organize behind the scenes.

Mollie is very different from Annie. She is old-fashioned, polite, stately, someone people listen to, and she’s the voice and face of their cause, commenting to reporters. giving speeches, but also turning up for protests, and doing the thankless work, like stuffing envelopes

Mollie and Annie’s cause? Ending racial segregation, everywhere in America.

Mollie’s latest idea, and she organizes it, is to pull together a group to hold a sit-in at Thompson’s Restaurant in Washington, DC. Thompson's doesn’t serve blacks. Mollie invites a local minister to lunch at Thompson’s. He points out that they won’t be served. “I know we won’t be served,” Mollie says, “but let’s go anyway.” They do. The result will be a lawsuit challenging segregated restaurants and stores in the capital of the US. The case will go all the way to the Supreme Court.

Annie adores Mollie. And the feeling is mutual. Annie, 36, is a half-century Mollie’s junior. Yes, Mollie is 86 years old.

Annie is from New York City, the daughter of immigrants, and grew up poor. Mollie is from the South, and grew up in privilege.

Annie is white. Mollie is black.

The year these two women meet, the year all this takes place? Not 1960, but ten years earlier. It’s 1950, five years before the Montgomery bus boycott, in which a mass movement challenges segregation. Four years before Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that makes segregation illegal. More than a decade before the “first” lunch counter sit-in, in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960.

These events I just listed are all considered important starting points for the modern civil rights movement, and if you’re American, you were taught them in school, or at least they were mentioned in that tedious textbook you tried to avoid reading.

And yet, here we are, talking about real black history, about civil rights activists in 1950, part of a history of black resistance in America that goes back to the 17th century, in an unbroken line. And Mary “Mollie” Church Terrell is no late bloomer: She’s been an activist for African-Americans’ rights since the 19th century.

This isn't the first time and won’t be the last time at NBH that what we think we know isn’t quite what happened. And it’s not even the last time in this post. As ever, its the details that make the big picture.*

*And that, dear friends, is why our kids need to be reading books, and especially books of their choice to follow their interests, not filling out worksheets to comply with standardization.

Four years of activism, working together, starting in 1950. Annie and Mollie had at least four things in common: They were women. They were friends. They cared passionately about civil rights. And they both knew what it meant to be hard up for money.

And if you think this is already mind-blowing, I’m only getting started.

Annie Stein, interesting though she is in her own right, drops out of our story here. This isn’t a story of black women and white women working together on civil rights, because that really had not been Mollie’s experience for most of her long life.

Look, long though Tales posts are, I can barely touch the surface of Mary (“Mollie”) Church Terrell’s impossible life (yet it happened). This is just the best I can do, riffing on Dr, Alison M. Parker’s Unceasing Militant, which I really hope I can entice you to read. Ooh, look, here’s a big hint..

Hey, Laing, you say, didn’t you aleady write about women suffragists in big hats? And Rosa Parks? Aren’t you writing kind of a lot about protesting women? Where’s the variety we know and love?

Chill, it’s here! Anyway, I reserve the right to get hung up on subjects. Hey, at least this post isn’t about FDR! Okay, well, yeah, he and Eleanor are in this book. They’re hard to avoid. For a decade at least, they were everywhere in American history. FDR doesn’t come off well in this story, but you’ll have to read the book to learn more, not because I’m dodging the subject, but because I don’t have room.

What Dr. Parker has done in this fab book is to take us behind the usual boring mini-biography that’s usually reeled off when Mary Church Terrell’s name comes up, a listing of organization presidencies and committees. Instead, Parker takes us to the place that Terrell really didn’t want us to go: Into her personal life. This isn’t just gossip. It matters. We come away from it, not with less respect for or interest in Mollie Terrell’s work, but with so, so much more.

Meeting “Mollie” Terrell

Mary Church Terrell is one of those B-list names from Black History Month. You may have heard of her. You may recall that name from a silly test, and with a shudder. You probably weren’t sure (until now) what she looked like. You—like me— almost certainly don’t know what she did. I mean, in contrast, the Black History Month “A” Team is pretty easy to recall. Think Harriet Tubman, rescuing enslaved people from the South. Frederick Douglass, big bushy beard, great speeches, etc. Check. But Mary Church Terrell? Um, let’s move on to Maya Angelou. Poetry! Poetry, we get. Committees? Not so much.

Some years ago, I read something longer than a sentence or two about Mary Church Terrell for the very first time, when I tackled her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World. Any historian will tell you that autobiographies have problems as sources. You only learn what the subject wants you to learn, in the way she wants you to know it. That can be enormous fun, but it’s dangerous if you’re seeking truth. I came away from this unthrilling memoir mostly with a very strong sense of poshness: Mary Church Terrell, educated at Oberlin College, one of the first black women to earn a B.A., and then one of the first to earn an M.A. That was cool. But a bit dull.

Terrell’s story after that seemed to me a very long, very worthy, and very boring string of leadership roles in black women’s organizations with long names. But either in that book or later, I forget, a Mary Church Terrell story caught my eye. It was about what happened when white women’s suffragist Alice Paul organized a women’s march on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration as US president in 1913. He opposed votes for women (and, by the by, was a massive segregationist). Alice Paul, worried about offending white Southern women and politicians, asked Black suffragists to stay home.

Remember, I’m a historian of early America. This isn’t my field. I thought I grasped this story well enough (and I did, according to what most historians knew of Terrell at the time) And then I translated it for a schools’ presentation. I imagined this as a really awkward telephone conversation between Alice Paul and Mary Church Terrell, and Terrell repeatedly responding to Paul asking her and other black women to stay home with a very polite, quiet, and insistent, “No, we’re coming to the march,” in my best posh American voice, until they reluctantly agree that black suffragists would march, only separately, and in the back. Black reporter and activist Ida B. Wells wasn’t having that, I told the kids. She single-handedly integrated the march, joining the white women of Illinois, her home state, who, in fairness (and to the surprise of my young audiences in the South) didn’t protest her presence.

Now I learn from Dr. Parker that this is not quite how things happened. I learned that black women, not just Ida B. Wells, did indeed march with white women that day. It wasn’t just that I had got this wrong. Everyone had got it wrong, she shows us, journalists and historians.

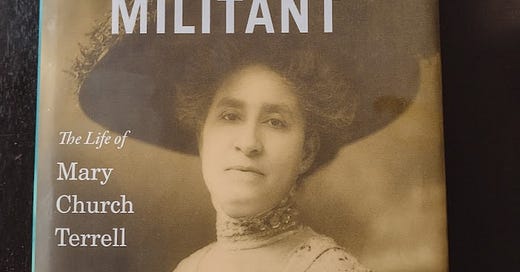

But what about the polite, ladylike Mrs. Terrell? Had I got her wrong? I mean, just look at the fabulous hat! And as for the word “militant” in Parker’s book title . . . That was a bit much, I thought. When I think of the word militant, I think of militant suffragettes in the UK. Well-dressed posh women who threw rocks through windows! They horsewhipped Churchill!!! They set fire to buildings!!! I’m sorry, but American suffragists wrote letters and made speeches, and that didn’t sound militant to me. I wondered where Dr. Parker was going with this.

Before I started this book, I looked doubtfully at that photo of Mrs. Terrell in her enormous hat, looking like one of those British suffragettes. C’mon, this woman never chucked a stone through a window.

I have had to adjust my thinking about what militant meant, and I resisted through most of the book. I was right to be skeptical about the rock-chucking thing, but not about the word “militant”.

But I didn’t have to adjust my thinking about what makes poshness, in the case of Mary Church Terrell. Well, except for the “being born into slavery in the American South” part. She was undeniably posh. I would have been afraid to be invited to tea at Mrs. Terrell’s, lest I put down the wet teaspoon on the tablecloth. Or washed my nose in the finger bowl. Or something.

Relative Privilege

So let’s start with the obvious question: How did a girl born into slavery become a posh person, and early in life?

Mrs. Terrell . . . Okay, I'll call her Mollie. Look, I have this total hangup about calling posh Victorian women activists by their first names (see Pankhurst, Mrs.) I feel like I'm violating their dignity. But since historian Dr. Parker calls Mrs. Terrell Mollie throughout, I am going to go with it.

Update: What I missed is that Dr. Parker refers to Mary Church Terrell as Mollie in her personal life, and Terrell in her professional life. Oops. My bad.

So. Mollie. Cough. Mollie was born into slavery, but into a family in which her parents were about as privileged as it was possible to be in slavery. Which is a very, very qualified statement, and I will explain why.

Their ancestry made baby Mary, and her parents, Louise and Robert, very lightskinned. But even when enslaved people were so white they looked like an inbred white person (like, er, me, in fact), they were not given a “get out of slavery and racism free" card. Lightskinned slaves, as white as they might be, were categorized as black by the law that “one drop of African blood” made someone eligible for slavery. Yeah, blood doesn’t work like that (and oh, Americans, you do love to talk about blood like this, and I cringe). A known African ancestor counted. That meant a person could be owned, sold, exploited in work, and used for sex.

Privilege within slavery is hard to measure. It's all grim. To illustrate, let's take a look at Mollie's dad, Robert. After the death of his mother, Emmeline, Robert Church, then aged 12, was sold to Charles B. Church, who was—to remind you— his biological father, his mother’s rapist.

Robert was not allowed contact with his father’s white wife, or his white half-siblings. He did not live in their home. Instead, Robert’s father employed him on steamboats he owned on the Mississippi River, in menial jobs like dishwashing, Later, he promoted Robert to steward, coming into close contact with white male passengers as a personal servant. This will matter.

Four years before the Civil War, Robert married Margaret (unofficially, since slaves were not allowed to marry in law). She was an enslaved woman who lived in New Orleans. They never lived together, but did have a daughter. Soon after she was born, Charles Church’s steamboats were captured by the Union Army, and Robert was stuck in Memphis, never able again to visit his wife and child in New Orleans. This was 1862. Slavery still existed, and its end was in doubt. Aged 23, and now valet to his own white father, Robert could not and did not see a future with his family. Instead, he unofficially married again, this time to 23 year old Louisa Ayres, an enslaved woman whose father and owner was a white attorney. Margaret, Robert's first wife, had also remarried by the end of the war and legal slavery in 1865.

When Louisa and Robert “married” (still not officially, still enslaved) their white father/owners stood as witnesses. Louisa’s father/owner paid for the dress.

So that was nice, wasn’t it? I can hear a posh Southern voice saying hopefully.

ACK!!! Don’t be absurd. No, it’s not “nice”. Good God. What is wrong woth you?? I mean, it’s all bloody bizarre. All of it. No wonder so many white Southerners clutched Gone with the Wind to their hearts, a fantasy brought to life, a pretendy history that never happened, and global publicity for their make-believe. There are white Southern people to this day who try to get me to pretend along with them that slavery was all nice and kind.

And truth? I’ve always tried to be friendly, but I’m fed up with this “kindness” crap in general, which increasingly means people (and women especially) being told to shut up about facts, just to be kind. I never, ever was going to pretend for one minute that slavery was basically just a bit of fun costumed roleplay among friends. Never.

The reality of slavery is just plain ghastly. This, folks, is why we need to talk truth, not just about slavery, but everything. This is why we mustn't agree on a stance at odds with overwhelming evidence, just to avoid giving offense.

Let's talk again about relative privilege when it comes to slavery (and racism), because understanding what that means, and doesn't mean, is key to understanding Mollie Terrell's life. And if she were standing right next to me, she would know what I’m on about. So let's talk now about Mollie's mum.

Louisa was the enslaved maid to her father’s daughter, Laura, her own half-sister. Weird though this situation was, it gave Louisa opportunities. Laura taught Louisa to speak French. Somehow, Louisa also became a skilled hairdresser and wigmaker while living in the Ayres’s house.

Now unofficially married, Robert and Louisa Church lived together in a room in the white Churches' home. And it was here that their daughter Mary (“Mollie”) was born, into slavery.

If the family's circumstances seem cushy by the standards of most people in slavery, they were. But do, please, consider this: While she was pregnant with Mollie, Louisa tried to commit suicide.

Mollie knew about this, as an adult. She worried about it, because she suffered from depression all her life. But Louisa and Mary had advantages that most enslaved people did not. They were lightskinned, which, given that racism permeated American culture, made them instantly more respectable, even in the black community. They had skills. And when they were free, thanks to the 13th Amendment (not their white relatives) Louisa’s white father/former owner set her up in business. selling wigs to wealthy white women in a store on the poshest shopping street in Memphis. This is not typical. Not even slightly.

Louisa was soon successful (not just because of hard work, please note, you can’t start a business without capital, aka money), and she bought the family’s first house, and first carriage (think car). Louisa also splashed the cash about.

Robert also went into business. Remember how he met wealthy white men on his dad/owner’s steamboats on the Mississippi? Now he hit them up for loans to open a bar and billiard hall in Memphis. He couldn’t get a billiard hall license because he was black, but he opened shop anyway, and he was arrested for operating without a license. Fortunately, just days before Robert’s trial, the third Civil Rights Bill of 1866 became law, making such discrimination illegal, and he won his case.

But hold on. In a terrible, horrible irony, being a successful black business owner made Robert Church—indeed, every successful black man in the South in the decades after the Civil War ended— a target for racists. A few days after Robert was cleared in court, on May 1, 1866, a white mob, led by police, attacked the city’s black community in what historians call the Memphis Massacre.

As Dr. Parker writes, “The mob murdered 46 black citizens, raped at least five women, and burned many African-American churches and schools to the ground.” Robert tried to save his business, which was looted and trashed, mostly by policemen. He was shot in the head, but, miraculously, survived. Weeks later, he was a witness at a Congressional hearing on the riot.

After this, Robert began carrying a gun, and Mollie remembered him waving it around when she was a kid, once when a train conductor called her a “little nigger” and tried to make her use a segregated carriage. Only the gun and her father’s white skin allowed her to stay put. This wasn’t the only incident in which Mollie witnessed racism, and her father’s defiance.

Robert continued to take Mollie to visit her white grandfather, who died when she was fifteen years old. Charles Church had not freed his son from slavery (the law had done that), and he didn’t leave him anything in his will, either.

This isn’t supposed to be Robert’s story, is it? Consider: Mollie was a child, but she was there. Her grandfather left her nothing, either. And I am often astonished by people who underestimate children, and don’t grasp how much they take in, and start to process.

Mollie also saw her father become a powerful man in Memphis. She saw how he worked with white businessmen. How he became a big wheel in Republican politics: The Republican Party was the Party that ended slavery, the party of Lincoln and of progress, while the Democratic Party in the South was the party of slavery and segregation. Later, things changed for both parties, big time, and that made life tricky for Mollie, who remained a Republican all her life.

By the time Mollie was seven, her parents were both successful businesspeople, and she lived in very comfortable circumstances in Memphis.

By the time Mollie was eight, her parents had separated, en route to divorce. Mollie was sent to school in Ohio, funded by her mother. It was a long way from Memphis. But her parents knew that the only school for black children in Memphis was underfunded. Mollie would never again live year-round with either parent. She lived instead with a middle-class black host family she adored, who ran a hotel and a candy store, and her father sent her a large enough allowance that she could buy all the candy she wanted, and that was good enough. She knew why she was there, what it was costing her mum, and she was glad to have parents who cared about her future. She was competitive and clever, and she worked her butt off.

Mollie’s education wasn’t just in the classroom. She experienced racism, white classmates denying that a girl could be both black and pretty, and she witnessed her white and black playmates taunting a passing Asian man. She told her black playmates that racism hurt them, too. And she told the white children that she liked the Chinese man’s skin color more than she liked theirs. You will not be surprised to learn she got into a fight, then and later.

By the time Mollie was twelve, her mother, tired of racist harassment because she was successful in business, had left Memphis forever, and moved to New York City. Mollie had done so well in school, her parents sent her to a more advanced school near Oberlin College, also in Ohio. She graduated high school at age 15, and enrolled at Oberlin, which was a progressive and integrated college. There she had a blast, and made good friends, black and white, and among the white girls was Janet “Nettie” McKelvey Smith, who was her friend for life.

Mollie did not take the two-year degree course for women, but the demanding four year course for men. Sometimes, she was the only woman in class, black or white, in subjects like Latin and Greek. Her friends told her that her intellect would scare off potential husbands. Mollie wanted to marry one day, but she also loved languages, and it’s testimony to her confidence that she cheerfully ignored such advice. She dealt with sexism as she dealt with racism: She treated them both with the contempt they deserved.

In summers, as an Oberlin student in the 1880s, Mollie stayed with her mother in New York, where she struggled to find a summer job: Whites told her she was qualified, but wouldn’t employ her because she was black. This was her first experience of finding it hard to find a job because of racism. It was not her last. Far from it. She also became one of the first black women to earn a B.A., and and M.A., and she did both at a highly-regarded college that was mostly white.

And then she left formal education, and went out into a world that expected her to submit to the will of her male relatives.

Robert Church told Mollie to come home to Memphis, and she did, only to discover her father was about to marry again, this time to Anna Wright, a school principal, who was only seven years older than she was. Mollie wasn’t shocked, and didn’t mind at all: She had known Anna for years, and she was very fond of her. But she had no interest in hanging around the house until she found a husband. Robert, however, was terrified at her suggestion that she pop out and get a job.

“Naturally,” she later wrote, “my father was the product of his environment. In the South for nearly three hundred years, ‘real ladies’ did not work, and my father was thoroughly imbued with that idea. He wanted his daughter to be a ‘lady’”

Mollie had run headlong into the gendered and class expectations of young women. Robert was far from alone among men freed from slavery, wanting the women in his family to stay home and live leisured lives, just like privileged white women. But Mollie wasn’t having this, either. She pointed out that she had been raised in the North among “Yankees” (Northerners) since she was eight, and that she “had imbibed the Yankee’s respect for work.”

Quick round of applause for Mollie from Annette: Other non-Southerners I knew often noticed when I was living in Georgia how the goal of many small businesses seemed to be to hand off the work to minions asap, so the owners could sit at home and nibble bon-bons, or at least sit in the back office feeling important, having delegated all the actual work.

This was very different from small businesses I have observed elsewhere, including in my own family, where the owners operated the business, and not from behind the scenes.

Going Her Own Way

As soon as Mollie’s dad remarried, she packed her bags, and headed for New York, to stay with her mother. Soon, she popped up in Ohio, teaching at Wilberforce University, a college for black students, most of them former slaves, and named for British abolitionist William Wilberforce. Only once she was settled in did she tell her dad she had taken a job. He wrote her a furious letter, and then refused to speak to her for months. Mollie was extremely upset. But, she wrote, “my conscience was clear, and I knew I had done right to use my training in behalf of my race.”

Still though, she was young, she was deeply hurt, and she took her father’s anger to heart. She sent pleading letters, she sent gifts, and, in short, she tried desperately to “appease his wrath.” She also knew by then that her dad had changed his will to accommodate his new wife, which meant that she and her brother would have a smaller legacy than they had expected.

It’s important to note again that, unlike Mollie’s mum, enslaved people almost never got money or property when they left slavery. They had zero opportunity to build wealth over generations. Let’s not exaggerate how easy it is to do that for the vast majority of poor free people, either. But for enslaved people, the key phrase is zero opportunity, zero money or property, zero advantages. The Churches were rare exceptions. They were lightskinned, which made them more acceptable to well-off whites who were their clients. Louisa Church came out of slavery with skills (literacy, fluent French, wigmaking) started in business with money from her white father/former owner. Robert Church didn’t get any money from his father/former owner, but, like Louisa, he also had what we now call social capital: He had the opportunity to meet rich white men as a steamboat steward on the Mississippi, and he grew up with the speech and manners of wealthy people. Fun fact: He taught himself to read, but he could not write, and throughout his life, he dictated his letters to others.

When Robert and Louisa did put their advantages to work, when they did start to make money, their consciences and their commitment to the shared community they had with the poorest of black people, required them to share their privileges with their community. I am reminded suddenly of Aneurin “Nye” Bevan, the Welsh coal miner and politician who founded the British National Health Service, who advised working-class Brits, “Rise with your class, not out of it”. Only, among African-Americans, the word was not class, but race, meaning skin color or, sometimes, just identity.

Like most—maybe all—members of the black elite, Robert, Louisa, and especially Mollie, rose out of their class, but took this responsibility to their “race” very seriously. As we’ll see, Mollie’s encounters with white people throughout her life did nothing to deter her from continuing her family’s commitment to the Black community, no matter how high up the social ladder she went.

Mollie decided to take another chance. Uninvited, she headed home to Memphis in the summer, and sent a telegram (today it would be a text) to let Robert know she was on her way. He met her on the station platform, holding out his arms. From then on, they were never estranged again.

After two years teaching at Wilberforce, Mollie was invited by a rich white woman to travel with her in Europe. She would be an equal travel companion, not a servant, and the trip would be expensive. She needed money from her dad, and he offered to pay. But then she got a great job offer she couldn’t refuse: Teaching Latin at the Preparatory Colored High School in Washington DC. She turned down European adventure for a job offer. And that’s how she met the man who would be her life partner, fellow teacher Robert Terrell.

Power Couple

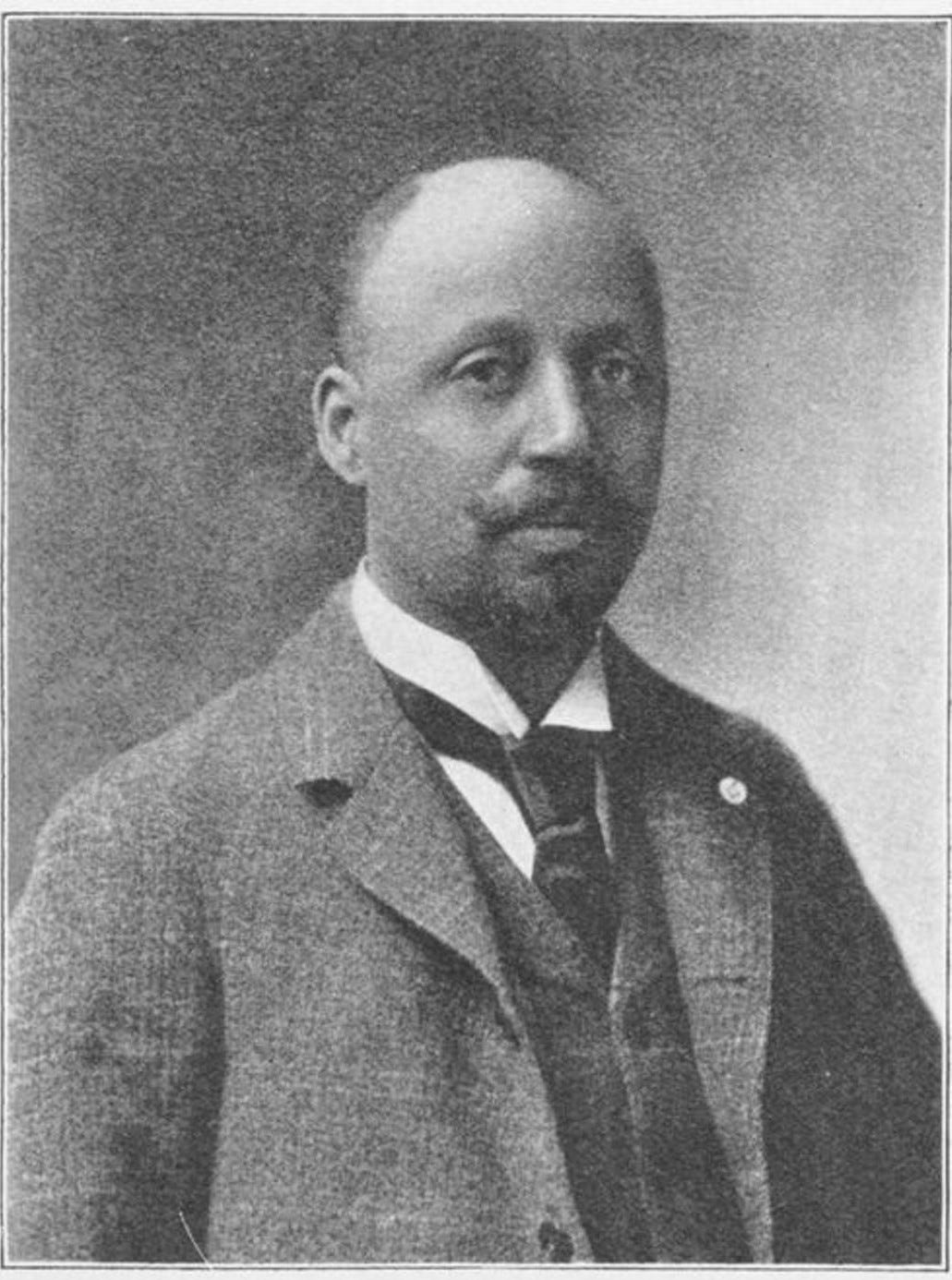

Robert Terrell (“Berto”) and Mary Church (“Mollie”), were both born into slavery, both well educated, both, independently and as a couple, successful in their professions, and in their elite social lives. They achieved what Americans call “prominence”. They were well known. And throughout the decades, historian Dr. Parker writes, they “supported each other intellectually, emotionally, and professionally.” By all accounts, Berto was a lovely bloke, laidback, kind, and sociable.

Berto was the product of elite Massachusetts boarding school Lawrence Academy (UK readers, think Winchester) and Harvard, where he had once worked as a waiter, and now was the third black graduate, and one of only seven students in his class to graduate magna cum laude (with high honors), the same year, 1884, as Mollie graduated from Oberlin, which was nothing to sniff at, either.

In short, Mollie and Berto were a power couple. Berto wasn’t jealous of Mollie. He didn’t feel threatened by her. He cheered her on, and that, she needed, because her confidence often deserted her, and she was prone to depression. Berto was, in short, a fantastic husband.

But wait a second! They weren’t married yet. Mollie wasn’t ready to marry. She took a leave from the school and her romance with Berto, and with the other Robert, her dad, she set off for Europe in 1888.

After three months of travelling, Robert (dad) left Mollie in Paris, and went home to Memphis, from where he continued to fund her travel and studies. Mollie traveled and studied throughout Europe for the next two years. She and Berto, meanwhile, exchanged letters, and each hinted at possible rivals.

Mollie had one serious suitor on her stay abroad: Baron Otto von Devoltz, a white Jewish aristocrat and lawyer. He offered her a life in Europe, far from American bigotry, discrimination, and segregation. She was tempted, but Otto blew it when he wrote to her father for permission to marry Mollie, without consulting her. Anyway, Robert disapproved of “interracial” marriages and he didn’t want his only daughter to live so far away.

Regardless, Mollie knew herself too well to take up Otto's tempting offer of a quiet and happy life. She knew she would be happier fighting the good fight against racism in the US, than living contentedly in Europe. If she did that, she wrote, “I doubted that I could respect myself.”

That decision would take Mollie back to America, and to Berto. They married in 1891. But not before Mollie hesitated again, even after the wedding invites went out, when she was offered a prestige job as registrar at Oberlin College. She even proposed delaying the wedding so she could take the job. Berto, understandably, was upset, having waited two years for her. So Mollie offered to end the engagement, which didn’t help at all.

She wanted to have it all, the man she loved and a high-flying career, as a woman, and as an African-American, in the 1890s. She made her sacrifice for her marriage, not without regrets. And Berto was her rock for life.

But despite their deep love, their marriage was never easy, and it got off to a very rocky start. This would be the background against which Mary Church Terrell became a major figure in civil rights history.

Jumping Ahead

Five years after she married Berto, Mollie Terrell was founding president of the National Association of Colored Women*, an organization dedicated to supporting and advancing all black people. That organization likely won’t mean much to any of my readers: It’s not the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), a household name in America, which was founded thirteen years later, in 1909.

*It will probably surprise you to know that NACW still exists, known today as NACWC, National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. Both organizations retain “colored” in their names in deference to their history: At the time they were founded, there was nothing offensive about calling black people colored. Times have changed, that’s no longer a preferred moniker, and members of both groups know that perfectly well, cheers, but history matters.

For now, instead of just reciting facts about groups with long acronyms, and making your eyes glaze over, let me try to get across what a big deal the NACW was in 1896: First national organization run by black women. First national African-American organization that was secular, rather than religious. And most of all, the NACW, writes Dr. Parker, was “the foundation of black political activism in the late 19th century.” So a very big deal. And, again, Mollie Terrell was its first president.

Not that it was easy. Despite the impression the public gets from the national determination to focus on a handful of leaders in black history, there were many ambitious, talented, and determined black women competing for too few leadership roles. Mollie Terrell won because she was a combination of upper-class charm, determination, decency, and a certain amount of steely ruthlessness or, better, strong competitiveness. She had many frenemies, including Ida B. Wells (kick-ass journalist and activist) and Mary McLeod Bethune (kick-ass educator, activist, and, later, leader of FDR’s Black Cabinet). The battles were fierce. But in the end, it was Mollie Terrell who, by 1901, was NACW President for life.

There’s so much more to this story, and Dr. Parker takes us through a fascinating blow-by-blow version, but this quick glance should give us a pretty clear picture of who we’re dealing with. How did Mollie get so much power? While her frenemies (and enemies) grumbled about and attacked her ambition (something, she noted, they didn’t do to men), the rank and file of the NACW loved her. They invited her to speak around the nation, in local, state, and national meetings. Molly Terrell was who they wanted to represent black women. She inspired them with her effortless posh gracefulness, her powerful speaking ability, her commitment, and her confidence.

Being part of the black elite after the end of legal slavery after the Civil War depended on many factors, but formerly enslaved people certainly could and did qualify. Higher education and business success were definite qualifiers. Money, jobs, activism for economic justice and/or civil rights also qualified. And (this part shocks a lot of white people, so steel yourselves, white people) so might skin color. Light skin was definitely considered an asset, and colorism didn’t vanish in a hurry. A white colleague of mine at Georgia Southern University (which had about 27% black students) once lectured about colorism. A shocked and impressed black student tackled her after class. “Dr. So and So,” she said, “You know about that?” Yeah. Well, historians. All that reading books and stuff. You know.

But any and all of the factors above could propel someone into the black elite, even if their social position was lowly by white standards. White elite members sometimes didn’t work at all, depending on investments and property for income. If they did work, they had access to occupations like law and banking. Black men rarely had such opportunities: They were starting from the ground, and in the face of fierce racism. Even being a barber or a post office worker might qualify you to be a member of the black elite.

And if you were successful as a Black American, you were expected (and expected yourself) to raise all boats with you, to work for the betterment of all black people, whether through politics, education, or economic opportunity. Black leader W. E. B. Du Bois (PhD, Harvard) coined the term “Talented Tenth” for the black elite, which I’ve always found a bit cringeworthy, because it’s elitist as all get out. But it did catch on, and Du Bois’s motives were good: The “Talented Tenth” were to use their advantages to the good of all black people, to battle racism.

Hard Times

Berto and Mollie Terrell, as members of the Talented Tenth, needed not only to be successful, but to ensure that their children were even more successful than they were, and to work all the while to help other black people achieve success. No pressure there, then. And they were expected to do all this when they started out as a married couple in the 1890s, a time of national economic depression without a safety net for anyone (that safety net came later, in the 1930s, with—what else—the New Deal).

This was also a time of rising racism and segregation.

In 1896, the same year that Mollie became president of the new National Association of Colored Women, the US Supreme Court declared in their Plessy v. Ferguson decision that separate public facilities for black people were just fine, so long as the facilities were equal. Of course, they weren’t equal, not even close. But it took another half century for the Supreme Court to admit that, in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1954. And meanwhile, Berto and Mollie were trying to navigate around racism that was more vicious than ever.

Two years after Mollie and Berto married, he lost his job. He had been working in the Department of the Treasury in Washington DC, a good-paying federal job that he got because he was a Republican. Don’t be so shocked: Political patronage, getting a job because of who you know, is still alive and well in the nation’s capital. But Berto’s fortunes changed when Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, had come to the White House, and Republicans like Berto were fired to make way for Democrats.

The timing was terrible: This was 1893, and the US had entered a horrendous economic downturn.

Fortunately, Berto was not unprepared. He’d been taking law classes at night at Howard University, Washington DC’s pre-eminent black college. He now started a law firm with his old boss from the Treasury Department. Their work included loans for black businesses and homes (white banks wouldn’t loan to black people), and handling real estate transactions in Washington DC, including those of Robert Church, Berto’s wealthy father-in-law in Memphis, Tennessee.

Loans and real estate were risky businesses at the best of times. In the midst of national economic disaster, Berto’s firm was soon in big trouble. Berto was making a great salary by any standard, but he was also stuck in business debt, and within a few years, Robert Church had to come to the young couple’s financial rescue.

During these years, Mollie had three failed pregnancies, and nearly died twice, before she finally gave birth to a healthy child, Phyllis, in 1898. She suffered from depression. Her mother Louisa, who was not nearly as well-off as she had been, moved from New York to live with the couple, and help care for the baby. Berto, needing a steady income, returned to teaching. If Mollie and Berto hadn’t had anxiety during these years, they would have been super-human.

The worst was yet to come. So was the best.

Plus my interview with author and historian Dr. Alison M. Parker:

Join us as an annual or monthly subscriber, or become a Patron, for access to all my work, online and in-person meet-ups, and (truly!) much more!

Fascinating and well written. Annette! Thank you for this deep dive into someone whose name I knew but whose story I didn’t.

Amazing story - such a challenging life and times. I'd never heard of her, but WOW, she had grit!!