Rosa Parks and Friends

Rosa Parks, a Cast of Thousands. Plus Annette Misses the Bus in Montgomery

How Long Is This Post? About 4,700 words or 22 minutes

Note from Annette

Still on schools tour! So I wrote most of this post originally in May, 2021, early in the life of Non-Boring History. I've abridged it, edited it a little, and ended it with a quick chat about my sort-of return to Montgomery last weekend, after nearly thirty years of avoiding the city. Last time I was here was in 1995, forty years after the Montgomery Bus Boycott, for a gobsmackingly awful academic job interview, a festival of ghastliness (not my doing, I swear) Until last weekend, that cringeworthy memory kept me away from Alabama's capital, although my feelings toward the state have been eased in recent years by one delightful gig as an invited lecturer at Athens State University, and another speaking to Birmingham's Doctor Who fan club. None of which has anything to do with Rosa Parks. . . . Onward.

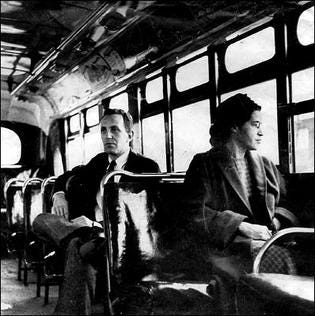

Rosa Parks, December 1, 1955

A bus in Montgomery, Alabama. A seamstress, a working-class black woman, refuses to give up her seat to a white man. She is tired. Is this how you recall the story of Rosa Parks? This is how most people do.

But no. This familiar story is about to take an unfamiliar turn. Even if you think you know where I'm going, even if you think you know the “true” story, prepare to be surprised.

1985: Will The Real Rosa Parks Please Stand Up?

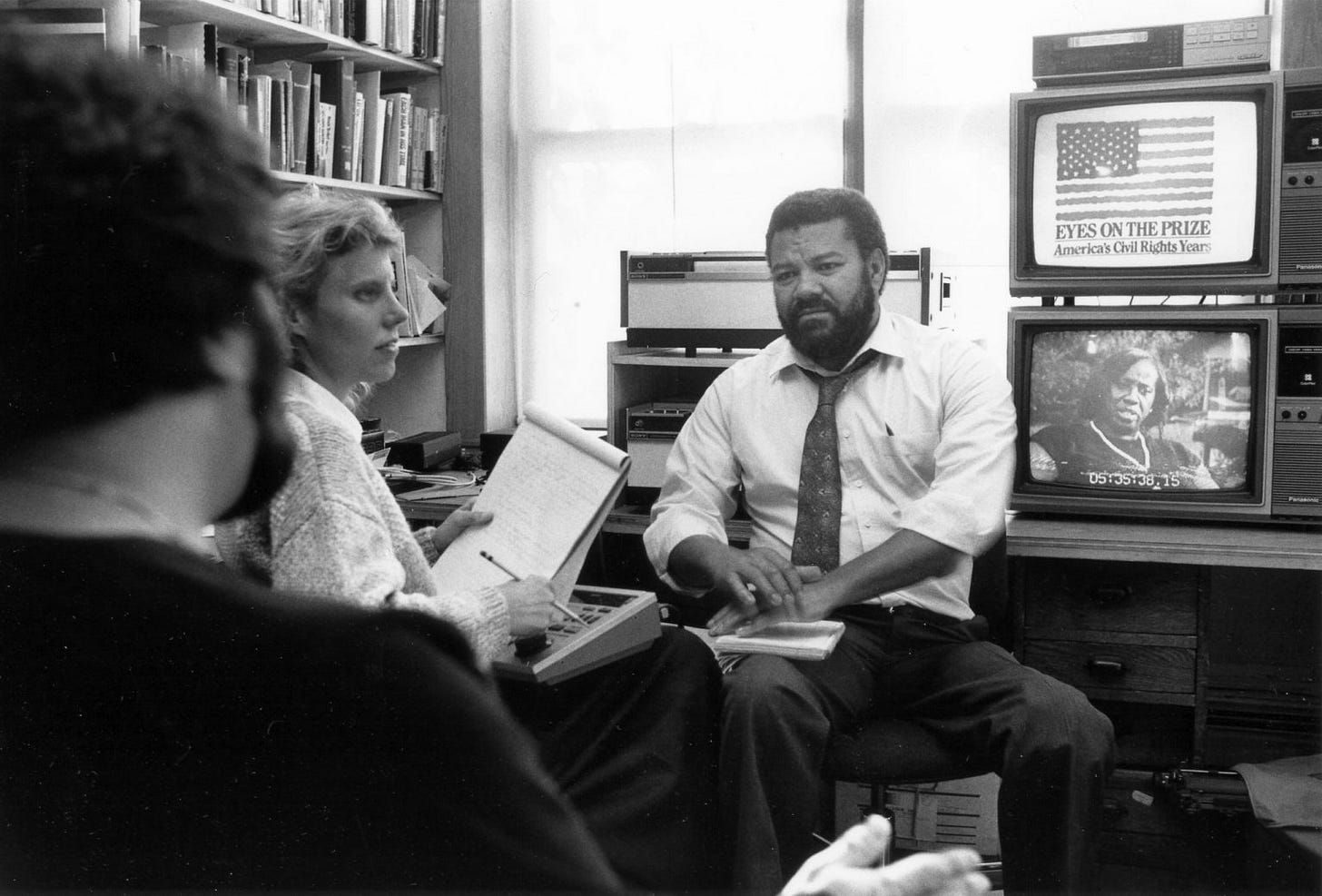

BEEP. The film crew is from Blackside, a black-owned film production company with a young multiracial staff. It’s been thirty years, and Rosa Parks has never been interviewed for TV before. She's soft-spoken, hesitant, tetchy at times. The film editor will have his work cut out for him. And then . . . .

Rosa Parks: I had been active much farther back than 1954, I had been working with NAACP since 1943. And I worked with uh, the uh, we set up registrations, __ meetings for people to start becoming registered voters. Very few of us were registered in the early 1940's. And, it was practically impossible to for a black person regardless of the intelligence to become registered except for a very few selected by the white community.

Wait . . . What’s this about the early 1940s? Rosa Parks was active in the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and as early as 1943? I thought she was a simple seamstress.

INTERVIEWER: WAIT, HOLD ON. OKAY, NOW YOU GET A CHANCE TO TELL ME HOW MR. NIXON, HOW YOU WORKED WITH MR. NIXON BEFORE THE BOYCOTT CAME ABOUT.

And who is this Mr. Nixon?? Not Richard, apparently . . . Another Mr. Nixon. Let’s hear Mrs. Parks explain:

Rosa Parks: Mr. E. D. Nixon was the very first person who told me the importance of registering and uh, becoming a voter. We uh, he and quite a few of the community people, my husband included, organized a Voters League we called it, we met in each other's homes and uh, a __ Madison, Mayor of Montgomery . . .

The transcript has this last bit wrong. Mrs. Parks says “Attorney Madison Nabrit of Montgomery,” civil rights attorney James Madison Nabrit Jr. Anyhow, some dude . . .

had come down from New York City to help us with our registration. His aim was to get people, get us registered without having to be approved by some white registered voter. We worked with that as well as with the NAACP. And Mr. Nixon at that time was the President, and when he wasn't President, he was the Chairman of the Legal Redress Committee and whenever any incident or anything happened in the community, we always called on him. So, he was the very first person who was notified by a friend of mine that I was in jail.

Let's be clear: This story doesn’t begin on December 1, 1955.

Rosa Parks: The call that I was permitted to make was to my home and I spoke with my mother and my husband and told them I was in jail. And my husband did find someone to give him a ride to jail to release me.

Wait. I know she was Mrs. Parks, but we never hear much of her husband.

But in the meantime, Mr. Nixon, [A]ttorney and Mrs. uh, Clifford Durr were there and they made bonds for me before my husband arrived.

There was nothing spontaneous about what happened that day. Mrs. Parks was allowed only one call from jail, and it was to her family. Meanwhile, E.D. Nixon, the head of the Montgomery NAACP, had swung into action. He arrived at the jail with a white lawyer, a native of Alabama named Clifford Durr. That’s surprising enough. But why did Cliff Durr’s wife come along for the ride?

Hold that thought. Now, come with me, because we’re flying to Boston in 1979.

The Marvelous Ms. Richardson and the Not-Yet- Marvelous Mr. Hampton: Boston, 1979

1979: Henry Hampton is disorganized, dedicated and (did I mention?) all over the place. His disability, the result of polio, is probably the last thing you think of when you think of him. He lives and works out of a huge, ramshackle ten-bedroom mansion built in 1834 in what is now a poor and violent Boston neighborhood, raising funds with the rental fees from the 24 (yes, 24) garages on the property (from which a chop shop once needed to be evicted, possibly at gunpoint). This man draws a steady stream of talented, skilled, and devoted people to orbit around him. And once Henry Hampton gets into your head, you are his.

Don’t worry, he isn’t operating a cult. He’s creator and owner of Blackside, a media production company, and he is executive producing a documentary about the civil rights movement. Or he wants to. Like everyone else at Blackside, he has never actually made a documentary. As he scrambles for experience, money, credibility, and connections, he knows the clock is ticking: As he tries to get his show on the road, the people who could tell the story of the civil rights movement first-hand are dying .

Henry Hampton has made great hires, and Judy Richardson is the best of the best. She’s researching, in an age before the internet, cell phones, even faxes, when research, to quote Blackside producer Jon Else, means

Library card catalogs, paper archives, newspaper morgues, letters, postcards, phone calls, and face-to-face talking.

As a young woman, Judy Richardson was herself part of the civil rights movement, a member of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee). She has credibility, contacts, and a winning personality. Henry Hampton wants to find the local leaders, the people overshadowed by Dr. King and the national figures, and especially women. Judy Richardson makes phone calls coast to coast, and, in Los Angeles, she finally tracks down Jo Ann Robinson, whom Jon Else describes as

the most important woman organizer of the Montgomery bus boycott, [and she] was an unknown . . .

Judy interviews Ms. Robinson, and she tells a vivid story. By 1992, she will be gone. But thanks to Judy Richardson and Henry Hampton, Jo Ann Robinson lives on.

America, We Loved You Madly

The interview with Jo Ann Robinson was recorded for the first documentary that Henry and his team produced about the civil rights movement, a two-hour job with the awful title of America, We Loved You Madly. They had shot some great footage. But then Henry flaked on writing the treatment (the description you give to the higher-ups at TV and film companies you hope will take on your project), and when he admitted this to the Blackside crew, with tears in his eyes, some walked out in disgust.

That same day, Henry huddled with Steve Fayer. Steve was his chief writer, a working-class Jewish New Yorker who once said “Henry had confidence in me when I had no confidence in myself”. They pulled an all-nighter at the typewriters, and they got the treatment done. The final documentary did not impress anyone: It strayed from Henry’s vision of civil rights movement participants speaking for themselves, and became more like other documentaries of the time, telling the story through the narrator.

Give Henry Hampton and Blackside credit, though: America, We Loved You Madly was the first attempt to do a documentary on the civil rights movement that wasn’t just all about Dr. King, as if talking about one black person meant you talked about them all. Henry and Judy knew better. Even before you start talking to the foot soldiers, who have their own stories, there is never just one leader. That's really not how it works.

Boston, 1985

Six years on. The bills pile up. But Henry Hampton won’t let go. He once said breezily,

I’ve never worried about being able to make a living. That’s part of the middle-class confidence that your parents gave you.

Blackside was never a non-profit. It was a for-profit (in theory), and it trundled along making corporate training videos and the like, running on fumes and Henry’s confidence. And he’s getting better. And collecting more and more of the right people, and telling them they are. That’s leadership.

Henry had loved the title America, We Loved You Madly. Everyone else hated it. Judy Richardson, back in 1979, had sent round a memo listing alternate titles from freedom songs, like We Shall Overcome, This Little Light of Mine . . . . and Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.

Now, six years later, over dinner in Boston, Steve Fayer and others try to persuade Henry to dump the title he wants for the new series. He won’t.

And that’s how the finest documentary series ever made became known as Eyes on the Prize.

Wait, Laing, what happened to the story of Rosa Parks?

This is the story of Rosa Parks. Henry Hampton and Rosa Parks and so many others made it. So many others? Meet some of them.

Jo Ann Robinson and the Mimeo Machine, December 2, 1955

It’s four o’ clock in the morning, and Jo Ann Robinson can hardly see straight. Ever since she got the news from Mr. Nixon about Mrs. Parks, she’s been churning the mimeograph machine at Alabama State University, the segregated college for black students in Montgomery. She’s been waiting for this moment for a long time. The Women’s Political Council of Montgomery, Alabama (Jo Ann Robinson, President) has been planning a bus boycott for years. This is the time.

Thirty-five thousand flyers are stacked and tied, announcing the boycott. Now, Ms. Robinson sits down and plans how the flyers will be distributed. She makes calls to her phone tree: She calls people, they call people, and those people call people. It’s what you did before the internet.

By 8 a.m., Jo Ann Robinson is standing in front of her first class of the day. She teaches English in a segregated college. The bureaucrats who run the place would be horrified to know of her use of the mimeo machine, because that's the kind of people they are. You don’t ask permission from people like that. Jo Ann Robinson has no qualms: she is president of the Women’s Political Council, an organization of middle-class Black women in Montgomery dedicated to political action against segregation. Jo Ann Robinson knows what really matters, and it’s not nicking a few reams of paper and some ink. Remembering the sight of empty buses on a cold and cloudy day, she later said, “I think that people had reached the point that they knew there was no return, that they had to do it or die. It was the sheer spirit for freedom, for the feeling of being a man and a woman.”

E.D. (Edgar Daniel) Nixon, Organizer, December 1, 1955

E.D. Nixon is former president of the Montgomery NAACP, and runs the show, whether in or out of the top office. A brilliant man with a grand total of 16 months of schooling, thanks to the system that deliberately denies any sort of education to most black people. On the railroad, he worked his way up to Sleeping Car Porter, one of the most prestigious jobs available to black men in the South. Then he became a union organizer. Like many middle-class Black men of his generation, he goes by his initials, E.D., so that white people won’t know his first name, and address him by it, at a time when white people are always called Mr. or Mrs. The bus system is just one of the many, many humiliations that segregation piles onto black people, and crushes them. It, they, didn’t crush E.D. Nixon.

Now, when Mr. Nixon confirms Mrs. Parks’s arrest, he contacts Clifford and Virginia Durr, and they accompany him to the jail. Bringing along a posh white couple of native Alabamians will speed things up, and of course, Clifford is a civil rights lawyer. This was planned. Mr. Nixon contacts Jo Ann Robinson and the Women’s Political Council. This was planned. He contacts a local minister, a young man who relocated from Atlanta to his first ever pulpit in the past year, and who hasn’t yet been convinced by other, done down clergymen to go along to get along. Mr. Nixon asks him to allow an organizing meeting in his church. Young Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. says yes, of course.

Clifford and Virginia Durr, 1955

White people? I’m bringing posh white Southern people into this story? Yes, I am. Listen to me, do. I’m a novelist who once forced my unsuspecting white readers to empathize with black characters (in One Way or Another), by giving them no choice.

And keep listening: The Durrs aren’t white saviors, or distant “allies”, and they aren’t just on the sidelines. The Durrs need their own post at Non-Boring History, and Virginia especially. Let’s just say for now that they are not typical native white Alabamians, not even typical white Southern liberals, and that’s why they’re so important. Virginia was raised a racist, like every white person of her generation in Alabama, but unlearned that as a student at Wellesley, the liberal arts college in Massachusetts. When she married Clifford, he expected her to be a posh housewife. Nope. While Cliff worked for the FDR administration in DC, Virginia was hanging out with Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune, leader of the President's Black Cabinet of advisers.

By 1955, the Durrs are back in Alabama. Clifford is a civil rights lawyer, and Virginia is a civil rights activist, convinced that life under segregation is just plain wrong. They’re under FBI surveillance. They aren’t Communists: In fact, Clifford once punched a man at a Senate hearing who accused Virginia of being a Communist. They are simply educated and decent people. They are principled. Courageous. Moral. And an unsung part of our story.

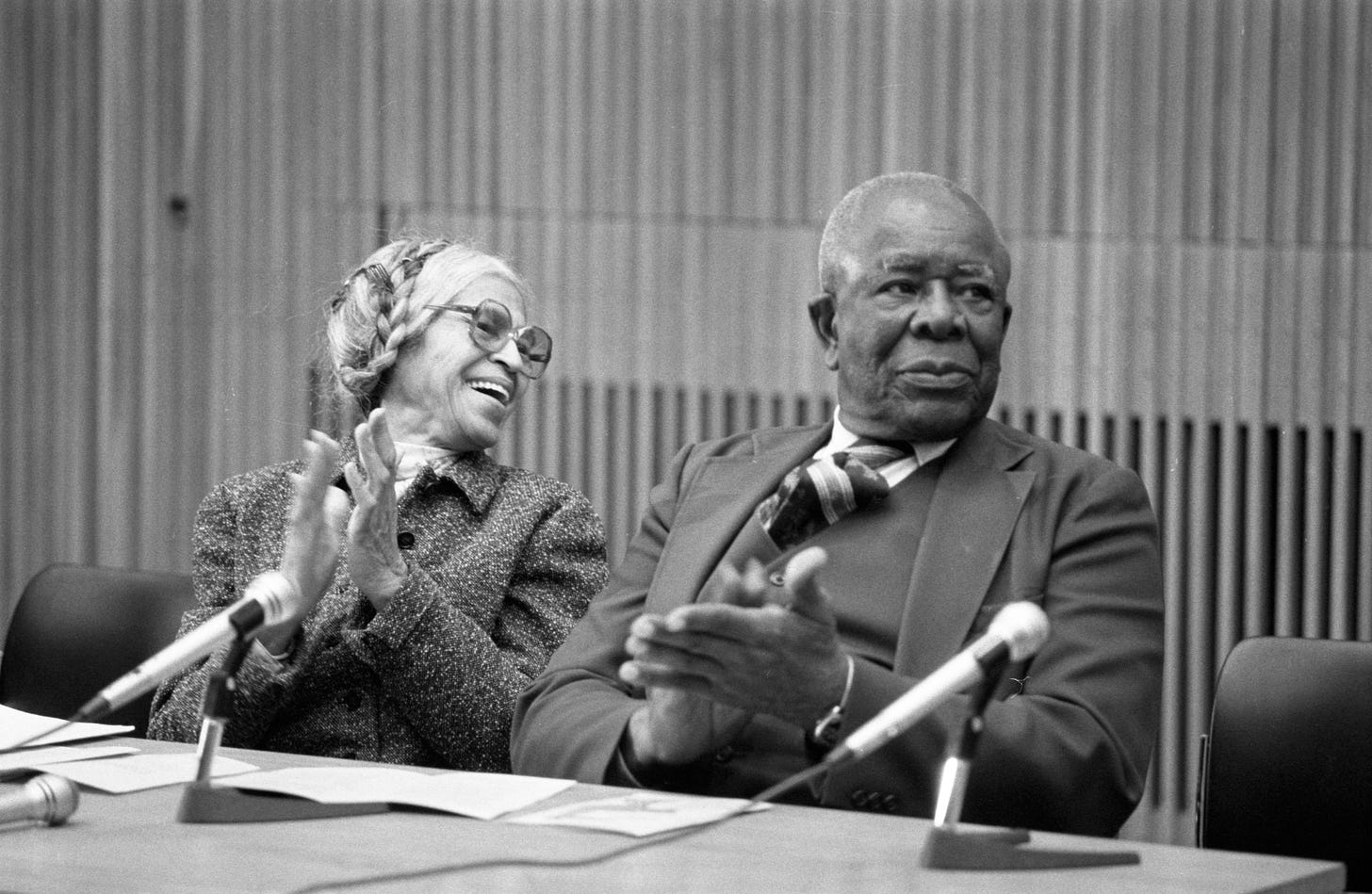

Oh, and yes, Virginia Durr and Rosa Parks become lifelong friends. Real friends. Having a laugh on the sofa together friends. Like this: