How Long Is This Post? Around 4,000 words, or 20 minutes

Today’s post belongs to my occasional Bits of History series, in which this academic historian riffs on curious objects from her random collection of junque valuable antiques.

I dunno, maybe it was being reduced to incoherent babbling when a hotel desk clerk held me up at camerapoint in the American South, for the terrible sin of being a middle-aged woman who grew annoyed (not angry, not shouting, just irritated) when he was rude to her at check-in, but . . .

Today, I realized, was a good time to pull myself together and remind myself that I am not Hotel Karen (with sincere apologies to Karens everywhere, because this meme especially sucks for you, and no, it’s never used about men, and no, “Ken” is not used instead, good try).

I am a mature woman from the UK (originally from Dundee no less, the home of terrifying working-class women). I remind myself that I'm the sometimes a bit daunted heir to an extraordinary British tradition of dauntless women who stick up for themselves.

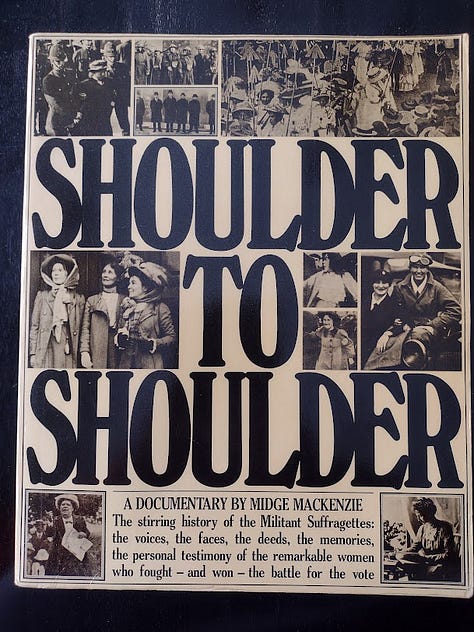

What better way to make this announcement, indeed, than with a Bit of History about my copy of Shoulder to Shoulder?

This hefty book, about the same size and thickness of an old telephone book for a small city (UK large town) is a treasured possession.

And yet I’ve never read it from cover to cover or, indeed, read much of it at all.

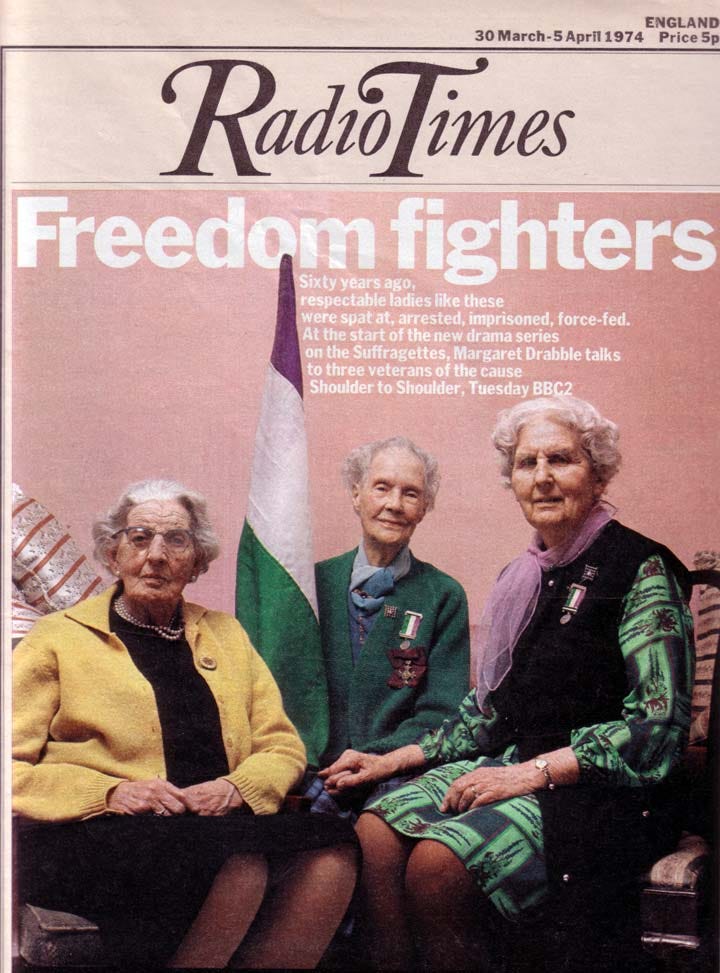

Shoulder to Shoulder was a gift from my parents for my tenth birthday. I was delighted. I have to hand it to my parents: They may or may not have shared my enthusiasm for the very serious BBC drama series which I had seen in the spring of that year, for which this was the companion book, but they knew how fascinated I was.

BBC’s Shoulder to Shoulder (1974) was a series of television plays, mostly covering the same period, from around 1905 to the start of the First World War. They were all about the battle for the vote for British women, and specifically about the women who became known as militant suffragettes.

Militant suffragettes (again, to remind my American friends, the correct term) were not content to write letters and petitions. They vandalized property, were arrested and imprisoned, went on hunger strike, and were forcibly fed. And that’s just for starters.

These TV plays covered mostly the same chronological ground, from the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) from 1903, to the beginning of the First World War. But they told stories from different perspectives, and especially the redoubtable Emmeline Pankhurst, WSPU founder, and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia, who were very much unalike. One play was focused on working-class suffragette Annie Kenney, a union leader used to cultivating working-class solidarity. Another traced the movement role of aristocrat Constance Lytton, whose participation severely damaged her health after she was arrested.

To emphasize: These women, supported by awesome men like Scottish Labour MP and former miner Keir Hardy (NOT to be confused with his namesake, the current leader of the Labour Party) and posh lawyer Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, were not like other suffragists. They were not safe, respectable letter-writing women like Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who recently was awarded her own statue in Parliament Square in London, a curious choice of subject.* These were militant suffragettes (yes, again, this is the correct term for those British women who broke windows and were imprisoned). The suffragettes were so celebrated in my youth, that a house at my all-girls school was named Pankhurst in 1976.

*I never heard anything much about Millicent Garrett Fawcett until years later, and I strongly suspect she gets her own statue now because, well, she never chucked rocks through windows.

In recent decades, even as Britain has became more diverse, even as more women were elected to office and emerged as leaders in business, the nation shifted to the political right. Margaret Thatcher was elected five years after Shoulder to Shoulder was first televised. Since then, the WSPU and its leaders seem to have faded into the background: The already largely hidden statue of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst in London was threatened in 2018 with being moved to behind the gates of a private university, where it would never be seen again by the general public. Honestly, it’s hard not to be a conspiracy theorist when you read something like that.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. This is old, cynical Annette. Let me summon young confused Annette.

Inappropriate, 1974

I was nine. Even before Shoulder to Shoulder appeared on TV, I was learning to love the past, despite (or perhaps because) I was growing up in a very modern town. I cheerfully drew little Anglo-Saxon people, and labeled and shaded in their clothes with my brightly-colored pencils. I loved our school trip to see the remains of Verulamium, the Roman city that once lived where St. Albans is now.

But when I saw Shoulder to Shoulder, everything changed. Despite what my war-hardened elders thought, life for a child in 1970s Britain wasn’t always a picnic. For one thing, my teacher in third grade (UK Year 4, or, in old money, second year in junior school) had been absolutely terrifying, a creature straight from Roald Dahl’s books. I was just getting over her when I discovered I faced another year of her in fifth grade.

Today, Pretendy 21st century Roald Dahl* would probably encourage us to be kind to this woman, explaining that she had WWII-induced PTSD, and he probably wouldn’t be wrong. But that’s small comfort when you’re eight years old, and she’s shrieking at you, and you’re terrified of being beaten in front of the whole class.

*The latest news in the brouhaha over rewriting Roald Dahl’s books to be more “sensitive”: Puffin Books will indeed commit this act of sacrilege by publishing Wokey Wonka. But its parent company, Penguin, will release a “classic” uncensored version that I expect will be called the OK, Boomer edition. Good try, Penguin and Puffin. Slow handclap. Hope this turns into a Classic Coke moment for you. Oh, the younger staff don’t get the reference? Google can help with that.

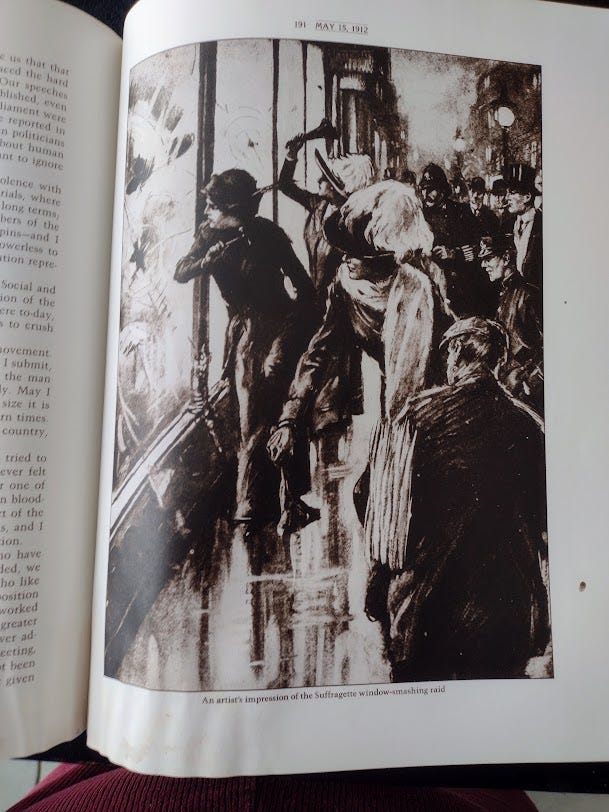

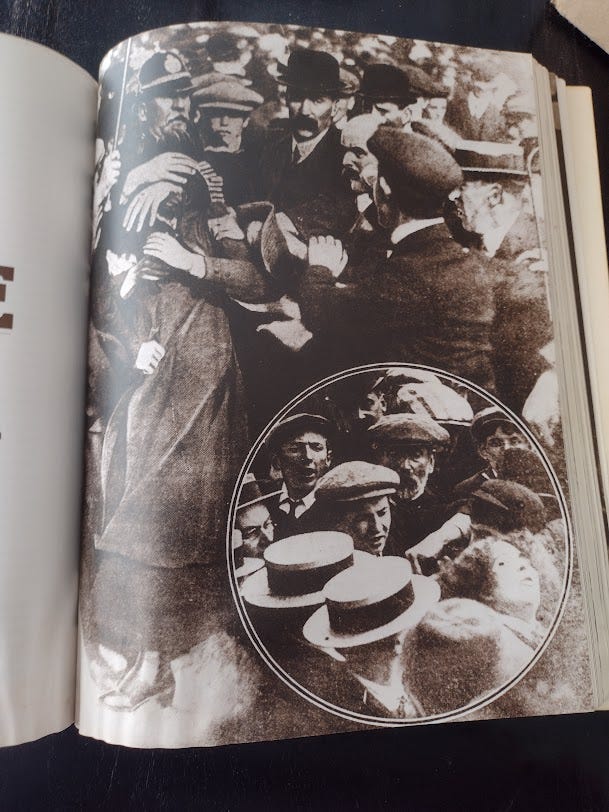

And then Shoulder to Shoulder popped onto the TV screen. My fears and hardships now appeared as nothing in the face of the historical horrors unfolding before my astonished nine-year-old eyes. I watched as posh women with impeccable Victorian manners chucked stones through shop windows, as they were brutally roughed up and humiliated by men (including the police), and arrested.

I followed the suffragettes into the Victorian nightmare that was Holloway Prison, with its cruel guards, and miserable dank cells. Agonized with them as they suffered hunger strike. And then (jaw hit floor about now) watched in horror as they were held down on their prison beds, as a doctor forced their mouths open with cruel steel gags, and forced hideous rubber tubing down their throats or —dear God—up their noses, and into their stomachs for what was called “forcible feeding”, but was unmistakably torture, painful and degrading, and ending in their piteous groaning and vomiting.

I realize this doesn’t make for pleasant reading, but, hey, history. This also is a tough subject to write about, even now, as I’m at the tail end of middle age, and especially knowing that these women, undeniably brave by any rational standard, were mocked as harridans and crazies at the time and for years thereafter. But I wasn’t then in my fifties, not in 1974.

I was nine years old.

I knew that I was watching acting, but, like most adults, I didn’t really understand, and really couldn’t: I also knew that this series was about as close as drama could get to what happened. My ability to differentiate between fact and fiction was permanently affected by Shoulder to Shoulder. Don’t worry, I’m not delusional, at least not all the time: The best history and the best literature aren’t as far apart as we like to think. Historical novelists (and I am one) have a huge luxury compared to historians (I am one of those, too): No matter how hard we try to be “accurate”, writers of historical fiction aren’t wearing facts and evidence and footnotes like a ball and chain. We can imagine what’s not documented, hopefully based on what is. Novelists often get at vital details that historians can only hint at.

Despite the complaints of some former suffragettes that Christabel Pankhurst was misrepresented as a selfish bully, and later allegations of elitism, Shoulder to Shoulder really did make a good-faith effort to get things right in 1974, sixty years after the events it portrayed, and before historians took the WSPU seriously. You can read a brief take on the series from 2014 by historian June Purvis, author of a very good biography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Watching the series more recently, I was impressed by the emphasis on conflict within the movement. That went over my head in 1974.

The project leaders were filmmaker Midge Mackenzie, actress Georgia Brown (who was fed up with crap roles women typically got in TV), and BBC producer Verity Lambert (mother of Doctor Who). Lambert hired Waris Hussein, the posh, gay Indian-British man who was Doctor Who’s original director. This was diversity in 1974. For whatever reason, they couldn’t get women as writers, but Brown, Mackenzie, and Lambert edited the scripts. I always imagine the writers as typical 1970s BBC scriptwriters, longish hair, cigarettes drooping from lips, tapping with two fingers on their typewriters. Not bad blokes, talented, meant well, just a bit clueless about women.

They did not write Shoulder to Shoulder, the book. Midge Mackenzie got the byline, but I daresay a team of researchers made it happen. It was not a work of history, exactly. It was a collection of primary source documents, the words of the militant suffragettes themselves, plus lots of pictures. It was definitely a coffee-table book, to be dipped into, rather than read cover to cover.

But, after all, I opened it for the first time on the day I turned ten. This was a book intended for adults. Today, there are far, far too many classrooms here in the US (and maybe in the UK?) in which I would have been told it was “inappropriate”, and not just —or even primarily- because of the searing subject matter.

No, the bigger problem we would have today? This book was not my “reading level”. It had not been approved for children’s rudimentary abilities in reading and comprehension. Today, had I somehow, miraculously, found it in a school library, many teachers would have told me to take it back to the library, and get something in accordance with my reading ability, even if I couldn't find anything I was so keen to read.

How do I know this? Because I have met an awful lot of school librarians. I know that school librarians, who are qualified teachers, have had a very different training from teachers in classrooms, and are fierce advocates for reading books, rather than, say, filling out worksheets. Too often, they are the only keen readers among the adults in the school. Oh, are you in California? Yeah, they fired all your kids’ school librarians a long time ago. Sorry about that.

“Reading levels” as applied to books are, let me be clear, corporate crap, “Levels” are decided by corporations which make vast sums of money by telling kids and teachers what kids should be reading. My son’s “recommended reading” , from one of these corporations, appeared on his school reports, and every book recommended for his “level” was awful tripe. I mocked this nonsense, and told him to ignore it, to read what he wanted. I don’t for a moment think it a coincidence that Hoosen, Jr., as a young adult, reads philosophy for fun.

I should say that this book wasn’t all that was available to me. Once I fell in love with BBC’s Shoulder to Shoulder, in spring, 1974, I popped down to the end of our street on the day the mobile library visited, parked next to the shopping center a hundred yards from my house, and cleaned out its surprisingly large collection of books on the suffragettes, at least some of which were for children.

But when, months later, I unwrapped my very own copy of Shoulder to Shoulder, this was the best of all. It was mine. I used my very own stamping set (before computers, this was thrilling, it really was) to place my name inside. This book belonged to me. Even now, kids prefer books in real copies, not ebooks, and especially books they own. You can understand why. It’s why I wince when I hear parents who could afford to buy their kids books insist they should get all of them from the library. It’s why I am so grateful to retired Georgia librarian Dusty Gres, who generously buys copies of my books to be given to kids in schools, so they can own their own copies.

I did try to read Shoulder to Shoulder. I couldn’t understand it. So I looked at the pictures instead.

That’s right: I looked at the pictures. You see, I couldn’t rewatch the series. No home VCRs yet, not in 1974, no way to review the bits I had had trouble understanding. I did own a one-off magazine featuring color pictures of the BBC production, which was also issued by the BBC (and is somewhere in my belongings, tatty but alive and well).

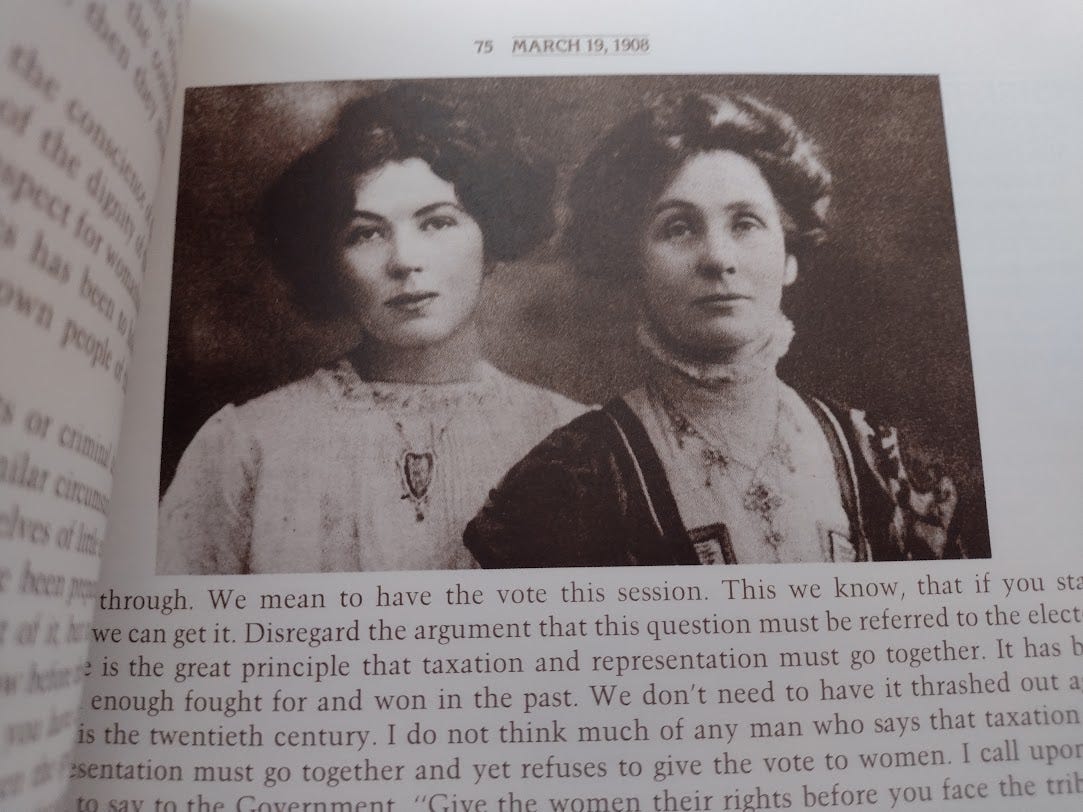

The pictures in the book, however, weren’t of the TV actors, but of the people they portrayed.

Actress Siân Phillips was taller, I think, than the tiny Mrs. Pankhurst (I still have a hard time calling her Emmeline: She was and is “Mrs” to me, forevermore), but she looked like her, and, I now think, Phillips likely captured her formidable presence. That’s Mrs. Pankhurst on the right, with Christabel on the left.

I was especially fascinated by a photo of Constance Lytton (properly, Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton) in her persona as working-class “Jane Warton”. As Lady Constance, sent to prison, she had been given close medical attention and preferential treatment. Determined to be treated as other women were, she assumed a disguise. As “Jane Warton”, she suffered the cruel treatment that was ordinary suffragettes’ lot in prison, and was repeatedly forcibly fed, which almost certainly contributed to the stroke she suffered after her release.

Having seen Constance Lytton's story dramatized in Shoulder to Shoulder, that photo fixed her story of enormous courage in my mind. Had I known she had lived just five miles from me, first in the grand stately home of Knebworth House, and then in the less grand but still posh Homewood in the village of Knebworth (where I went to the dentist), I would have been astonished. She would still have have seemed a million miles from me, and not just measured in time: The (by now) Lytton-Cobbolds of Knebworth were very posh, I was not. As close as I ever got to Constance Lytton was when Lady Cobbold, a relative, and a current inhabitant of Knebworth House, opened a summer fete (US festival) at my children’s club (US Think Boys and Girls Club).

And it wasn’t just the recognizable personalities that caught my attention in the book. It was images like these:

I never forgot this, either, the photo from the cover of the Radio Times (US TV Guide), of these oh, so respectable old ladies who, the caption pointed out, had once been imprisoned and forcibly fed.

One Woman’s Freedom Fighter . . .

Historian June Purvis has argued that the series focused too much on the WSPU aiming for the vote, and not enough on the WSPU’s goals of full social equality for women, which the series suggests was mainly the department of Sylvia Pankhurst, who split with her family’s organization and started a group in the poor East End of London. What also wasn’t mentioned in the series, and I now find striking, and I know Purvis has downplayed this, too, is some of the more gobsmacking reasons why they were imprisoned in the first place. Yes, the series showed them committed acts of violence against property, including popping a Molotov cocktail in a mailbox.

But what I wouldn’t grasp until quite recently was that the suffragettes planted bombs. That would have stunned me, because another thing I recall vividly from 1974 was my absolute terror at the Irish Republican Army's campaign bombings of train stations, cars, even historic sites, within forty miles if my home.

But even knowing what I did know then about the suffragette’s militant actions—the yelling, the vandalism of paintings, the setting fire to mailboxes— I don’t know how to reconcile these things with their heroic status. History, done properly, teaches us that unreconcilable things often co-exist, including in our own minds. My most profound early lesson in thinking historically came not from instruction, but from watching high-quality television, and looking at pictures. This was also an early lesson in how to teach history. But let me be clear: To really understand the past and its relationship to the present, you have to listen, write, and, above all, read. And I did.

My nine-year-old imagination was fired by a TV series not intended for kids, and sustained by a much-treasured inappropriate book. For the first time, history wasn’t just curiosities from the past. It was about real people, complicated and often contradictory people. My interest in the suffragettes soon faded into the background, satisfied for now, but my love of history —and reading non-fiction—was ingrained. And more recently, Shoulder to Shoulder has floated back into my awareness, even before the suffragette colors of gold, purple, and white were nailed to the mast of the gender-critical movement, and a woman wearing a suffragette scarf was kicked out of the visitors’ gallery of the Scottish Parliament.

Today

As I write, I’m listening, for the first time, to Dame Ethel Smyth’s comic opera, The Boatswain’s Mate (1916). I’ve come to enjoy Dame Ethel’s work, which makes sense, since I’m a fan of Edward Elgar, Vaughn Williams, and other early 20th century English composers. Dame Ethel was a suffragette, and a composer who had studied in Leipzig, Germany.

I am sitting here astonished, as I hear a familiar tune. Dame Ethel incorporated into The Boatswain’s Mate the tune of The March of the Women, the militant suffragettes’ battle song for which she wrote the music, and which was also the theme tune for BBC’s Shoulder to Shoulder. Dame Ethel was portrayed marvelously in Shoulder to Shoulder, by actress Maureen Pryor, who depicts her conducting suffragettes singing The March of the Women in Holloway Prison, waving a toothbrush from her cell window.

That actually happened. Dame Ethel was a larger than life character. In Leipzig, she met Brahms, Dvořák, Grieg and Tchaikovsky. She was a lesbian who dressed in the more “mannish” clothes of the period, and smoked like a chimney, at a time before women smoking was accepted. None of that helped her get taken seriously, because she wasn’t judged by her “gender identity”. She was judged by her sex. She was a woman. And thus, it was decided, she could not possibly have been any good at writing music. At the time, she did earn the friendship and admiration of Arthur Sullivan, as in Gilbert and Sullivan, so well done him. But then, for decades, she was ignored and forgotten. Even when I started listening to Dame Ethel’s music in recent years, I was astonished by how good it was.

In 2021, Dame Ethel Smyth finally got the recognition she was always due as a composer: She won a Grammy, seventy-six years after she died.

The Medal

Many, many years later, forty-four years after Shoulder to Shoulder, to be exact, I visited the Museum of London for a special exhibition.