Hate's Modern Masters 1

ANNETTE TELLS TALES Racist massacre in a hi-tech city, and the progressive men behind it

The curtain rises on a veritable devil’s cauldron. An atmosphere overhead, usually resplendent with electric lights, blackened by a sheer swirling dust and powdersnake, beneath, the faint glimmer of blue steel, the brandishing of dirks, the dull thud of wielded clubs, the whir of stones, the crash of glass, and the deafening report of guns . . . the dreadful faces of . . . an organized . . . mob.”

—J. Max Barber, Atlanta, Georgia, quoted in Gregory Mixon, The Atlanta Riot

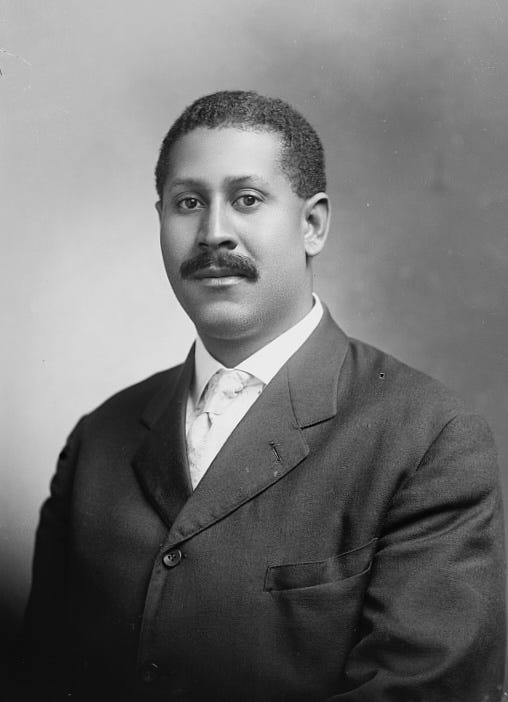

Max Barber Sees Barbarians

Jesse Max Barber just watched out-of-control angry white men rampaging through the streets of downtown Atlanta.

Tonight Max Barber’s life is in danger. That life makes a mockery of the mob’s desperate belief that anyone white was innately superior to anyone Black. Born into freedom, college-educated, and ambitious, Max Barber, at 28, is already editor of The Negro Voice, poised to become the #1 magazine for black Americans. He’s also a political activist. Last year, 1905, he was a co-founder of the Niagara Movement. That's a national group of elite black Americans tired of being denied their rights as US citizens.

Atlanta is a growing modern city, a place for optimism and opportunity. But tonight, Max Barber just saw a nightmare playing out among its tall buildings and under its electric lights. And note: He called it an organized mob. And he wasn’t wrong: Not disciplined like an army, but organized all the same. But by whom?

On this night in Atlanta, Max Barber was not specifically targeted. Anyone black was the barbarians’ target. Anyone. Any black man— or woman— would do. The mob of white men couldn't tell the difference between a messenger boy and Max Barber. In a way, that was their point.

Note from Annette

Without setting out to do this— seriously— I've somehow lined up an entire NBH series of posts involving mobs, all incredibly important, and all very different from each other. First up, this two-parter. It’s about Atlanta, the capital of Georgia, but it's not just for readers who care about Georgia, or even know where it is. This is about modern cities, about division and exclusion. It’s about a city whose elite’s late 19th century big-city ambitions were sort-of fulfilled (unlike those of poor Port Townsend, WA which I wrote about recently.) but at enormous cost to its people and the US.

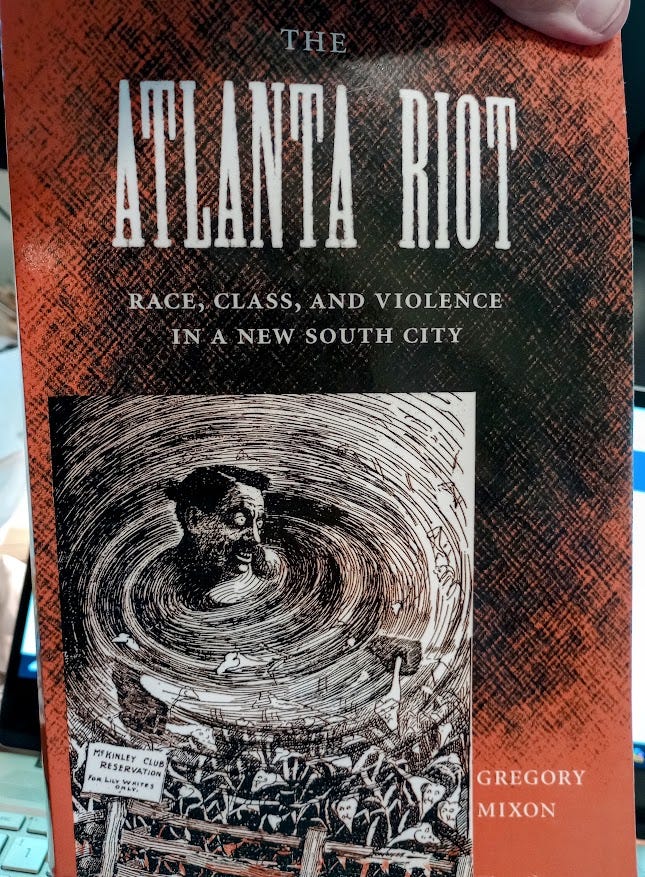

Today, I’m riffing on historian Dr. Gregory Mixon’s The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, and Violence in a New South City.

Since Dr. Mixon’s book appeared in 2006, the 1906 Atlanta Riot has been dubbed the Atlanta Race Massacre. That's a more accurate name for it, but a bit of a mouthful, so in my version of his story, I’ll call it the Atlanta Massacre, and its participants rioters, since massacrers is not a word.

What Happened and Why

Dr. Mixon describes the Atlanta Massacre itself in one of his last chapters. That's fine for a scholarly audience, because academic history is mostly focused on questions, on whys: Why Atlanta? Why 1906? Why should we care?

But I’m starting this riff with the Massacre, based on Dr. Mixon's chapter, because, well, I don’t write for an academic audience. I write for you.* I have to hook your interest first.

*Mind you, there are historian colleagues reading this. Hi, guys! I see you! Thanks for supporting me as I try to make what you do relevant! Not yet a Nonnie? That was a hint! 😃 Oh, and I welcome your critical feedback, especially if you are Gregory Mixon. You know how to reach me.

Because this is Non-Boring History, I'm also going to pull you into Gregory Mixon's interpretation of what happened, and show you why it matters.

George Blackstock Boards a Streetcar

George Blackstock lives six miles east of downtown Atlanta, in Decatur, a rural town that electric streetcars have transformed into an Atlanta suburb. But tonight, again thanks to those streetcars, he’s in Oakland City, to the southwest of Atlanta.

George Blackstock is an ordinary white workingman. He hurried to Oakland City after hearing false reports from two days ago, that a black man raped a white woman on her farm. Now, he’s about to head downtown. His only reason? To take out his anger on any black person who gets in his way. In his words, his goal is “to hurt niggers.”

It's the evening of September 22, 1906. The US Civil War ended more than forty years ago, A whole new Atlanta has grown up from the ashes of the old, burned to the ground by Union forces in 1864.

Since then, thousands of people have flocked to the Big City for the chance of a better life. Many of them are Black people, no longer enslaved, no longer tied to rural land and to the people who own it. Atlanta offers freedom. Excitement. Jobs. New ways of living. For black intellectuals, there's community and willing students in Atlanta’s rising Black colleges. For businessmen, the city is a huge pool of customers with cash.

And so, in 1906 Atlanta, Black colleges look down from the city’s hills, and Black businesses thrive in the downtown business district, where Black and white Atlantans mingle, even as Jim Crow (a nickname for the new racial segregation laws) tries to drive them apart.

Electricity lights up Atlanta. It powers the city's efficient and flashy hi-tech public transit system, the streetcars in a large and growing network, with overhead wires linking each streetcar to its electric power source. Atlanta’s streetcar network now extends all the way to small towns like Decatur, home of George Blackstock.

Everyone can ride Atlanta’s streetcars in 1906, if they can afford a ticket. But they don't experience them in the same way. Streetcars are segregated by “race”. Race is a bogus concept with huge power in America, from the 17th century to the 2lst.

Now, in 1906, slavery is illegal. But racial discrimination is very much legal. Segregation was confirmed ten years ago by the Supreme Court in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which endorsed racial segregation on public transport. Now, in 1906, segregation is increasingly part of everyday life in Southern cities, even the self-consciously modern city of Atlanta.

Black people in Atlanta are not barred from streetcars: Their money is welcome. But they are otherwise treated very differently than whites, and very much unequally.

Each car is segregated by a moveable sign. As more white passengers board, black passengers are required to move to the seats in the back of the streetcar, and to stand if necessary.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court had said that segregated facilities must be equal. In practice, separate is never equal. The arrangements aboard streetcars are just one more demeaning and daily reminder of even the most successful black Atlantans’ weirdly inferior status in a city where Black colleges and businesses thrive.

Whites, meanwhile, are not happy either. Atlanta’s corporate streetcar companies in 1906 don't provide completely separate cars for blacks and whites. To do that, they would have needed to run more streetcars, and that would have cut into profits. Instead, the compromise is the signs. Whites complain that they are forced to sit next to black passengers so the streetcar companies can make more money. That will turn out to be a really significant complaint if we're going to understand what's going on in 1906.

One of the white streetcar passengers arriving downtown this evening of September 22, 1906, is George Blackstock, who boarded the streetcar as an ordinary workingman. By midnight, George Blackstock will be leading a group of white men as they batter down the doors of a restaurant owned by Mrs. Mattie Adams, a black woman.

What Happened? The Night of Saturday, September 22, 1906

From Dr. Mixon’s Chapter 7, I’ve put together a timeline of most events in the Atlanta Massacre.

Around 6 p.m.

White men gather in the downtown business district, along Peachtree Street, the main drag (later made famous by novelist/Confederacy fangirl Margaret Mitchell in Gone With the Wind), and Decatur Street, home to many black-owned businesses.

By 9 p.m.

The crowd of white men becomes a mob. They begin rioting in the streets, armed with sticks, clubs, knives, rocks, bricks, and guns. For the next several hours, until after midnight, they will attack black Atlantans at random.

Around 9:30 p.m.

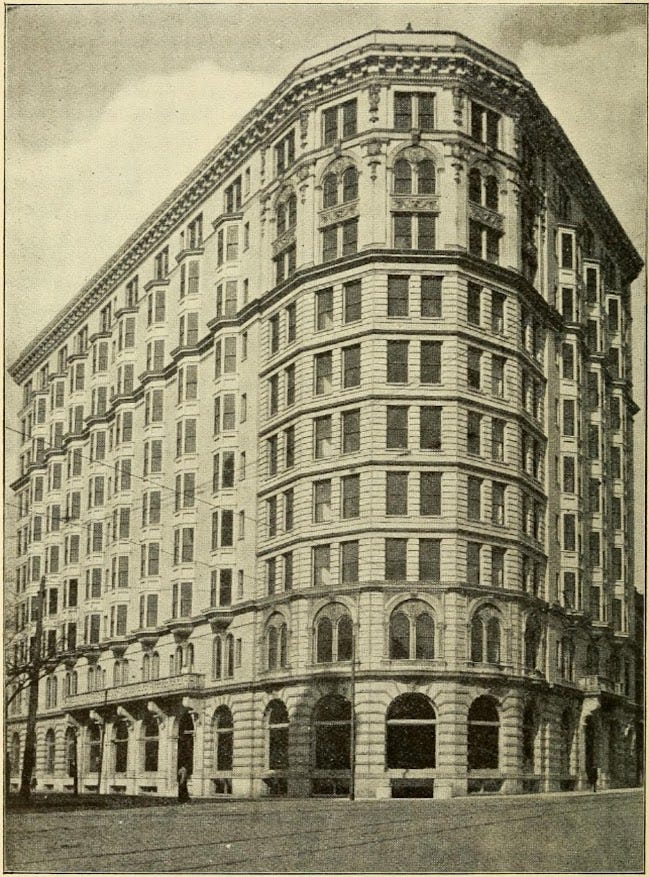

Atlanta Mayor James Woodward and other city bigwigs, like former police commissioner James English, stand in front of a crowd gathered outside the ten-story Piedmont Hotel. Owned by Georgia’s soon-to-be governor Hoke Smith, this is Atlanta’s most modern and glamorous hotel. It was opened just three years ago, and it’s a symbol of the city’s prosperity. Mayor Woodward begs the white rioters to stop their attacks. The mostly working-class crowd replies with a “Bronx cheer” (aka blowing a raspberry, or making a farting noise with lips and tongue). When ex-police commissioner James English tries to speak, they yell that he’s a “nigger lover” and tell him to “shut up”.

Now another fake rumor that another white woman has been sexually assaulted by a black man sends the crowd surging toward Black businesses on Decatur Street.

9:30 to 10 p.m.

Thousands of white men are flocking into downtown Atlanta on electric streetcars, to join the mob. The mob attacks random black Atlantans on the streets, while the authorities struggle to regain control. Perhaps five hundred black Atlantans take refuge in a skating rink, under police guard. However, Dr. Mixon notes, the white mob shows no sign of wanting to confront a large crowd of black men: They instead pick off black people in small groups, or individuals.

A black messenger boy on a bike is attacked by a mob of young whites. He’s rescued by (white) police officers.

The Mayor orders the Fire Chief (who is also Atlanta’s Mayor-Elect) to turn fire hoses on the white mob on Decatur Street. The crowd run away, laughing at the firemen, and yelling that they’re sorry they voted in the Fire Chief as Mayor. Their words lead to an abrupt change in the Fire Chief’s orders: After that, the hoses are turned on the black men who had gathered on Decatur Street to resist the attack. The mob finds a black man hiding in a pool hall on Decatur Street. They shoot him, and he later dies in Henry W. Grady hospital.

Three hundred policemen are now on the streets. While some individual policemen help black Atlantans, most seem concerned largely with keeping the white mob safe by redirecting them away from black neighborhoods where they might meet resistance. Cops also stand by while black passersby are assaulted and murdered, and while white rioters loot hardware stores for guns and other weapons.

10 - 11:45 p.m.

At 10 p.m, bars and theatres close, and ten thousand white men are now on the streets, attacking black pedestrians, including deliverymen and messengers.

Hearing a rumor of a black man knifing a white man, four or five hundred white rioters, led by a coal company foreman, surge back down Decatur Street, toward the Piedmont Hotel. There, they “mercilessly torment” a random black passerby as revenge for the supposed knifing.

And starting at 10 p.m., the mob turns its attentions to Atlanta’s streetcars. Sometime during this hour, the cops give up, and let the white mob get on with it. Streetcars become deathtraps for black passengers.

A white mob unhooks streetcars from their electric power lines, and the vehicles, full of black and white passengers, grind to a halt in Atlanta’s central business district. On Peachtree Street, right in front of the modern Piedmont Hotel, the mob smashes the windows of fifteen streetcars. They drag black passengers out through the broken glass, and passengers who try to defend themselves are beaten across the heads with sticks.

Some of the mob chase a black person down Peachtree Street, to the busiest part of downtown, at Edgewood Avenue. There, they shut down more streetcars, and smash the windows. White policemen cover two bleeding black passengers with their bodies to protect them until the motorman manages to recover power, and drives away. When another crowded streetcar arrives, in which black men sitting near to white women, the mob orders the whites off, and then attacks the black passengers, women as well as men. Six black women and four men are dragged from the streetcar, and battered with sticks and iron bars.

The remaining women passengers on board the streetcar fight back with umbrellas and hat pins, before they and the remaining men are overcome, and dragged out through the jagged glass of the broken windows. The women are stripped, hit across the heads, and some are “allowed” to escape. While some black men are able to run down side streets, a teenager named Evans is cornered. He tries to defend himself against the mob, before being swarmed, beaten, and thrown to the ground. Bloodied, he somehow stumbles to his feet, and pulls a knife in self-defense. The mob beats him to death.

The white motorman of the attacked streetcar at Peachtree and Edgewood manages to climb on the roof of his vehicle, and reconnect the electric wire. He then rescues his surviving passengers by driving away. But, by then, three of his passengers, all black women, are dead.

I’ll let you catch your breath here. I know, right? Hard reading. And, I assure you, hard writing.

From another streetcar, three black men are thrown from a viaduct onto the tracks, a drop of ten feet, and then shot dead. Others aboard are beaten up.

Altogether, the white mob destroys eleven streetcars, and kills at least eleven people.

Brutal assaults continue on the streets: One victim desperately tries to hide next to the Henry W. Grady memorial statue on Peachtree Street. The mob finds him and batters him to death. They chase and catch a well-dressed light-skinned barber on his way home, and cut open his chest. A man has his eye almost “punched out”. Other black men are knifed, pummeled, and left badly injured.

Midnight- 1 a.m.

George Blackstock of Decatur is among between seventy-five and a hundred white men who head up Peters Street, home to many black businesses.

Blackstock leads others in battering down the door of Mrs. Mattie Adams’s restaurant. They beat Mrs. Adams and her adult daughter with spokes ripped from wagon wheels. They shoot bullets at her grandson’s feet to make him “dance.” They smash up the restaurant. As they leave, they run into a black man with a gun, and they kill him. A black person shoots at them from a window with a shotgun, injuring one white rioter.

The Peters Street mob now decides on a revenge march on a black neighborhood where, four years earlier, a black man named Will Richardson had killed several policemen and white civilians. On the way, they loot a hardware store and a pawn shop for more weapons, including guns. One working-class rioter, a machinist called J. W. Briggs, tells the mob they should not be attacking white businesses: The mob, angered by the criticism, turns on him, but another man saves him. Three policemen are trying to stop the riot when Milton Brown, a black passerby, walks out of an adjoining street into a nightmare. He tries to run, but he’s shot in a hail of bullets, and later dies at Henry Grady Hospital. “His sudden appearance,” Dr. Mixon writes, “had diverted the mob from confronting a black community instead of solitary individuals.”

A black pedestrian has just stepped off the Forsyth Street bridge when a white man clubs his skull, “the sound of contact being heard for a block.” Two or three of the mob then shoot the victim repeatedly.

Around midnight on September 22, 1906, streetcars filled with whites are still heading into Atlanta. Some are passing through an African-American area on Edgewood Avenue. when shots ring out, aimed at the streetcars, but nobody is hurt. For that one incident, a group of seventeen Black men are later arrested by white militiamen. Among them, according to the militiamen, are black men who “talked impudently”—in other words, who did not show the groveling respect to white authority that whites expected and demanded from all black people.

There’s no safe place, not even on US federal government property. Black people flee for safety to the downtown Post Office, right next to Henry Grady’s statue, and are refused protection.

And at some point tonight, the white mob smashes the windows of a successful black-owned barbershop. It’s a symbol of black success.

And the barbershop’s success was success that had happened within the limits set by the white South, agreed to by designated national black leader Booker T. Washington (but not by all black leaders, let’s be clear) in his 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech: Leave us to make a living in jobs and businesses that don’t compete with you, he told his white listeners, and we promise not to tread on your toes, not to seek to hang out with you, or marry your daughters, or get political power. This barbershop is what Washington had in mind: Staffed by black men in the humble job of barbers, it serves white male customers.

Tonight, the two barbers working do not resist the mob. One has a brick thrown in his face all the same. Both are shot, and their faces mutilated. Their corpses are stripped for ghoulish souvenirs, before being dumped, alongside a black passerby who was also shot by the mob, near the Henry W. Grady statue. This statue, as Dr. Mixon writes, was “a monument to the spirit of the New South.” So much for the Atlanta Compromise.

Urban, post-slavery, a place of opportunity, modern, a thriving place of business, downtown Atlanta has emerged as a shining capital, not only of Georgia, but of the New South. Tonight, it is a horrific, bloody crime scene, a place of open, violent hate by thousands of white men against all black people.

At least thirty-five people died on this one night. Most were “respectable African-American working people”, in Dr. Mixon’s words. Only one victim was white. The mob had aimed to get black people off Atlanta’s streets. They had succeeded.

On this day, the world had changed. And, no matter how it looks, the Atlanta Massacre had not been spontaneous. It was organized, even though it doesn’t seem that way at all.

Behind the Horror

Please don’t go, now that you’ve read about the awful events of that night in Atlanta. Please don’t draw a snap conclusion, like “Oh, that’s just white people doing bad things to Black people, the usual story, end of.”

That’s not why I write Non-Boring History. That’s not what academic history is about. I don’t want to do more harm than good. I’m not here to affirm what my readers already think, or (forgive me) to entertain you with a horror show that happens to be true.

Academic history isn't entertainment. And it’s not about learning about the past for the past’s sake. It’s not about generalizing about the past, and it’s not just about thinking for ourselves, because just thinking often leads straight into tin foil hat territory. History is about thinking on the basis of as much knowledge as possible.

What you think is happening may not be what is happening—that's one of historians’ mottoes, said in a rueful voice.

So, first, a word on victimhood in a situation in which people clearly were victims: Black Americans have never just been pushed around in history. They have always exercised agency, as historians say. They have resisted, objected, undermined, pushed, stood up, and fought back for their rights as people, against slavery, segregation, and discrimination, and even on the worst of days, like September 22, 1906.

Evidence? Look again at the story above. Yes, there are victims taken by surprise in an instant, like the pedestrian clubbed before he could realize what was happening, who could do nothing to defend himself. But look again. See the women on the streetcar wielding umbrellas and hatpins against a murderous mob. See the frightened young teen known to us only as “Evans”, taking his last stand in a hopeless situation, waving a knife at a mass of armed men bent on killing him. Look at the barbers making rapid calculations in their heads, deciding not to fight back when they’re hopelessly outnumbered, trying to be able to go home to their families. These are all forms of courage, and that is Black American history, centered on what Black people have done, not what was done to them.

The Atlanta Massacre is best understood as American history, and how Americans came to label people, and how “white” and “Black” became not just attempts to describe skin color, but identities: One in the service of exclusion and even hatred, the other in the service of human dignity. And it’s about how powerful people have an impact on the public opinion that influences everything.

Here at NBH, I fight best I can against the revival of what historians call Whig history, the history of Great Men, powerful individuals who are assumed to make everything happen.* I try showing why history is never, ever that simple, and why thinking of history in that way is seldom helpful to understanding what's happened, then or now. But this is also a story about powerful men making things happen, and in this case, I think we should highlight that.

*Reader, you know I love FDR (sorry, conservative readers, but please check out the Living New Deal to see the amazing value taxpayers got from FDR’s programs) But he couldn’t have got anything done by himself. His greatness lay partly in hiring lots of smart, enthusiastic, and decent people, and partly in being inspiring.

We should also want answers to pressing and serious questions like these:

Why on EARTH did this horror show happen?

Why in 1906?

Why in Atlanta, specifically?

Why does it matter now, and not just to people in Atlanta, Georgia, the South, and the US?

It’s time to go beyond the horrors of that day in September, 1906, as I riff on how Dr. Gregory Mixon pulls back the curtain on what and who lay behind the Atlanta Massacre.

Who were the white mob?

Most of the white mob were young. Most were working-class. But don’t stop there: Dr. Mixon says the rioters also included students, businessmen, craftsmen, shopkeepers, and office workers. Lower-middle class men of all kinds. Most of their names, we don’t know.

But don’t stop there, either. Please.

Watch the crowd through Dr. Mixon’s eyes. Imagine him poring over newspapers, over personal letters, over every word. Imagine the horror movie playing out in his head. As some white men repeatedly stabbed two Black men outside the posh and hip Piedmont Hotel, an approving, well-dressed white crowd stood by to watch, Men. Women. Children. They yelled encouragement to the attackers. Respected elite white men joined in the murderous assault, and then strolled back to rejoin the sidewalk audience.

The rioters were staging an audience participation show for the approving well-dressed crowd. They allowed black people a running start, and when the victims took off, white attackers tore after them, waving clubs and knives, as the crowd cheered. This isn't just about ordinary white blokes attacking innocent black Atlantans, although it is.

But still don’t stop there.

What We Think Is Going On Might Not Be What’s Going On: An Example

The Atlanta Massacre has roots long before 1906: Slavery existed around the world, but in America before 1865, it was based on “race”. That’s a bogus concept that goes well beyond skin color or identity, and what a mess it’s made. Every time we're asked on an official form in the US today to give our “race” (not ancestry, not skin color, not identity, but “race”), however well meant, it reinforces our mistaken sense that “race” is real, that races are separate lanes we cross at our peril.

But “race” is a belief, a powerful and convincing belief, you bet, but a belief all the same. It grew out of racism, a convenient notion that skin color and cultural differences are signs of fixed and serious biological differences among human beings. As America changed after the Revolution, as Northern states abandoned slavery while the South retained it, racism became more and more pronounced, more angry, and weaponized to support and excuse slavery’s continued existence in the South. Let me explain.

Back in the 1700s, whites could and did say to themselves, “Sure, Africans are really just like us once you get to know them, but it’s their tough noogies that their God-given fate in life is to be enslaved in America, putting them in an inferior status. Too bad, so sad. Glad it’s not me.” Okay, they didn’t put it quite like that, but you get the idea.

However, racism hardened after the American Revolution, and not by coincidence. When Northern US states (like Massachusetts) began making slavery illegal, Southern states like Georgia were increasingly isolated in allowing slavery.

Southern whites began portraying slavery as a social good, not just a necessary evil, and believing their own propaganda. With a tinge of pride, they began calling race-based slavery the South’s “peculiar institution”, that’s peculiar as in specific to the South, not peculiar as in completely bizarre. White Southerners now also doubled down on the bonkers pseudo-scientific “idea” of people being innately different because of superficial physical appearance.

So their excuse changed. No longer was it, “Shame about that, but someone has to do the crappy work, so it might as well be someone who doesn’t look like me”. It changed to “God intended Blacks to be inferior BECAUSE they are inferior. Obviously. Otherwise, how could I, a good Christian, justify owning another human being and forcing them to work for free? Why, really, when you think about it, I look after them. They’re like children, really. Yes, that’s it! Phew. Thinking is hard work. Caesar, bring me an iced tea. I'm going to lie down.”

That’s a bit of context. But real historians can’t stop with a general sweeping statement about slavery and racism to explain specific events, any more than scientists explaining disease can just say “germs done it”.

We need to know why the Atlanta Massacre happened, and why it happened where and when it happened. Dr. Mixon’s book shows us that the Massacre didn’t happen just because of deep roots of racism and slavery. It was the result of particular things happening in the city, the state of Georgia, and the nation in a few years, months, and days leading up to the day itself.

This is history that really makes sense of then, and helps each of us make sense of now. The historian’s word here is contingency: Nothing is bound to happen, everything that happens depends (is contingent upon) a set of particular factors falling onto place. There are always other ways that things could have gone. And things could have gone differently in Atlanta in 1906, despite segregation, and despite prejudice. Historians’ job is to explain why they went the way they did. Gotta admit, though, contingency is a very useful way of thinking, isn’t it?

Hey, Laing!

Yes?

I noticed some white Atlanta police and some white civilians came to the aid of black Atlantans on September 22. So they weren’t all racists, then?

Thank you for asking! Okay, what you think is going on might not be what’s going on. I trot out that favorite motto of historians not to gaslight you, but because understanding what happens depends on lots of historical context. As I said, what happened in 1906 in Atlanta comes from a long historical legacy. But it also depends on many factors particular to Atlanta in 1906. Just one example, to address your question, 19th century attitudes about race still existed side by side with newer and even more disturbing attitudes among white people in early 20th century Atlanta.

So yes, most Atlanta police officers colluded with the white mob on September 22. And some white Atlantans, including police officers, worked to protect some Black Atlantans. Let’s look at why they did. The police were supposed to be keeping order, so there’s that. But let’s look at whites who were not police, but nonetheless came to the rescue of black Atlantans targeted by the mob. Consider the heroic streetcar motorman, who was —I say this confidently— as racist as the mob, but who wanted no part in the murder of his passengers, who were his responsibility. Or here’s a more clear-cut case: Consider J.D. Belsa, a white theatre owner who locked his black employees in a safe room, and stood guard all night with a shotgun.

J.D. Belsa’s response, as Dr. Mixon explains, reflects that he basically held the same values as the rioters: To restore what he understood to be the values of the 19th century, of the slavery era, as interpreted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy: A white boss should protect his humble and grateful black staff. This wasn’t just a selfless act of compassion and human decency. How am I so sure? It couldn't be, not in Georgia in 1906, where absolutely everyone was marinated in racism. Belsa’s perspective was as much if not more a reflection of the wishful thinking of the old plantation masters: Blacks were like children, and needed protection (unless they stepped out of line, in which case, they were ruthlessly crushed). This was what’s called paternalism, a fatherly attitude, if by “fatherly” you mean one of those deeply terrifying fathers who traumatize their kids.

But J.D. Belsa represented an old-fashioned attitude in a time of change. Modern racism expressed by the mob forecast a future that shut out most black people from downtown Atlanta. And this attitude was also emerging among Atlanta’s elite: The modern luxury Piedmont Hotel employed few black people, the owner preferring white immigrants to serve his posh customers. Yet he protected his few black employees during the Massacre. Both attitudes would persist into the future, all the way to the present, but nobody could know that in 1906. What seems to be happening in 1906 is the rise of an all-white future for Atlanta. This was what, alarmingly, some white writers called “a final solution to the Negro question.” And if that phrase makes your blood run cold, well, it really should. You know what’s worse? It’s not a coincidence. Adolf Hitler took a keen interest in American attitudes toward race, and he took notes.

Annette’s Aside You may be having trouble with my riff on Dr. Mixon’s interpretation of whites helping black people during the Massacre as an expression of something other than human compassion. I get that. I’m not ruling out human decency: The motorman, the policemen who protected black passengers by covering them with their own bodies. But those things don’t rule out the ugly side of paternalism.

Let’s think of very rich people today who are “kind” to their close employees, as if people were pets, helping them in times of personal need, like buying them new glasses when they need them, but who don’t pay them a living wage so they can live independently, and buy their own bloody glasses, thanks.*

*This example is real, by the way, and it’s from Georgia, around 2010. The business owner who boasted to me of helping her employee also couldn’t understand why the same employee wasn’t eager to give up her church choir practice to put in extra hours at work “when we’ve done so much for her.” I tried to explain why that might be. I didn’t get far. I was put on her “enemies list”. Very Georgia. I say that as a Brit who lived there for nearly a quarter century.

Now ask, honestly, if those same “kind” employers care whether people who are not their employees even live or die. Plus thinking in terms of “kindness” implies talking down to people: We are kind—in this sense— to dogs and small children, but it’s not great when we look down on adults. This is not a partisan or racial comment. I’ve seen such attitudes among the wealthy across party lines, and regardless of color. Such attitudes are never as simple as they seem.

Black Self-Defense

Human self-respect had to mean that black people protected themselves, not just relying on powerful whites to serve them human rights when convenient. Many Black Atlantans were prepared on September 22 to defend themselves, their families and communities, from the mob. Afterward, many were themselves charged with “rioting” for simply preparing for self-defense. Among them were three women: Jane Simon was fined for “flourishing a pistol,” or, as many Americans think of it now, openly carrying a gun as a murderous mob stormed through her city. The other two women brought to court had simply been urging black men to fight the white mob.

These women were being told it was not their job to defend themselves, and they were scapegoated. By the way, black men were told the same thing. Think of that poor lad, Evans, waving his little knife at a murderous mob.

Progressive May Not Mean What You Think It Means

Days before the Atlanta massacre, Progressive speakers at the Georgia state Democratic Convention assured their audience, in Dr. Mixon’s words, “that whites no longer need fear federal protection of black rights.”

Laing, wait . . . What? Georgia Progressives said what?

Yeah. They said that. And I’m not about to tell you that Progressive meant something completely different in Georgia in 1906. Noooo. It didn’t. This kind of thing is what makes Dr. Mixon’s book so gobsmacking.

Americans, you remember the Progressive Era [UK Edwardian] from high school, right? Ooh, vaguely, you say uneasily.

Ok, so you may recall learning about “settlement houses” These were large houses built in poor immigrant neighborhoods, and operated as community centers by well-meaning middle-class ladies like Jane Addams, at Hull House in Chicago. [UK readers: Look up Toynbee Hall, or think of Sylvia Pankhurst in the East End]. They helped poor people, especially immigrants, toward becoming educated, trained, and, not coincidentally, middle-class like them.*

*Annette’s Aside: I’m fed up of being preached at by so many upper-middle-class Americans from privileged backgrounds that this sort of thing is unacceptably “bougie” (as in embarrassingly bourgeois, or middle class, not the French word for candle). If I hadn’t been exposed to Brits who thought like the settlement house ladies, I might be bagging your groceries instead of writing for you. So there.

Oh, did you know that black settlement houses were also a thing? Yup, Ida B. Wells, journalist and civil rights activist, and Jane Addams’s friend, was among middle-class Black women who set up settlement houses in Chicago and other cities to serve African-Americans who fled the South. This is another clue that I’m also telling a story about class in America.

Laing, we don’t have class in America. Everything’s about race.

Hahahahahaahahahahahahaha! Oops, sorry. You’re right. And you’re wrong. Stay tuned.

Maybe my American readers remember Progressivism being about improving democracy? Maybe you recall California Governor Hiram Johnson pushing for more people power using the initiative, the recall, and the referendum, new tools to put decisions directly into the voters’ hands.*

*Not saying this is a good thing or a bad thing. But it is a thing.

I agree, it feels weird to lump Hiram Johnson, Jane Addams, and Ida B. Wells with a bunch of raging bigots in Atlanta, but that’s what I’m going to have to ask you to do. Come through the looking glass with me into Georgia, in 1906.

And let’s just say it: The Atlanta Massacre was deliberately stirred up by elite white Atlantans who considered themselves modernizers, progressives, and reformers.

I must have misread you, Laing. These elite white people who you claim caused the Atlanta Massacre considered themselves progressives?

They did. They were. They had lots in common with Jane Addams and Hiram Johnson, and even Ida B. Wells. They wanted to see economic progress in Atlanta. They wanted it to become a modern city, and they wanted ordinary people to have a better life. The difference? The Atlanta elite only wanted that better life for white people. And black rights, they believed, black people got in the way of that economic progress. The elite’s version of Progressivism was what we might now call a zero sum game: Black people had to lose their rights and gains for white people to gain theirs. In fact, this elite hated and feared black people as much if not more than poor whites like George Blackstock.

That’s why racism was not just tacked on to their progressive views. Racism was central to Georgia Progressives’ version of Progressivism, for Atlanta becoming the “city of progress” they wanted it to be. As Dr. Mixon observes, “For African-Americans, the ‘city of progress’ and Progressivism meant the very opposite.”

With slavery long gone by 1906 (at least in law) Georgia’s white progressive elite believed that Atlanta’s success and white people’s prosperity depended on as much power as possible being taken away from black people. It meant rolling back the political, economic, and social gains that black people had made since the Civil War. The white Atlanta elite wanted all this gone. All of it. They had plans for a bright future of growth and profit and prestige. But the few Black people they grudgingly might allow to be present in the city were expected to make themselves as small, humble, and invisible as possible, as much like the false stereotype of slaves (as peddled by the Daughters of the Confederacy) as possible.

And the most powerful men of the white Progressive elite in Georgia saw their vision of a shiny, all-white, modern future as key to their personal political success, as we shall see.

Black Atlantans, including the Black elite, had not yet figured this out by 1906. Of course they hadn’t. The white elite’s vision was incredible to anyone capable of decent and reasonable thought.

So who were the villains of the Atlanta Massacre? I don’t normally do heroes and villains, but when people are deliberately injured, maimed, traumatized, and killed, there are villains. We started with one villainous name standing for thousands whose names we don’t know: George Blackstock, ordinary working man, riding a streetcar into downtown Atlanta with the deliberate goal of hurting black people. But Dr. Mixon shows us that the actual participants in the Massacre were not the only people responsible, or even most responsible, for what happened. Men like George Blackstock were being used. The real villains, the organizers, were behind the scenes.

So who exactly were the shadowy bunch of elite Atlantans behind the Massacre, how did they make it happen, and how did they try to cover up their involvement? This is the most important story of all.

Introducing The Atlanta Commercial-Civic Elite

I’m well aware that you have probably never been to Atlanta, except maybe changing planes at the city’s massive airport that’s complete hell to get around, just like Atlanta itself. Ever wonder why the airport in Atlanta is so busy? Why all roads in the US South lead through Atlanta, and why those roads are so clogged? The answer to those questions starts with the city’s late 19th and early 20th century Commercial-Civic Elite, as Dr. Mixon calls them.

Atlanta has from the start been a transportation hub. Its first nickname was Terminus, the place where the Western & Atlantic Railroad ended. But how Atlanta is now begins with the Commercial-Civic Elite. These were powerful white men who began taking charge of the city after the Civil War. The Commercial-Civic Elite wanted the new Atlanta to be the South’s transportation hub, sure, but they wanted it to be much more than the place where the trains met: Indeed, the new Atlanta was built a level up from the old, so the trains ran below the level of the streets. These men wanted Atlanta to become a major city, what today we would call World Class.

By 1906, the leaders of Atlanta’s Commercial-Civic Elite were actively and quickly moving to control everything, and everyone, politics, society, economic development, not just in Atlanta, but in Georgia. The Atlanta Massacre proved central to that successful power grab.

But who were these men of the Commercial-Civic elite? The answer might surprise you. They were not former slaveowners, who by now were either very old or very dead, and whose power and wealth had been based mostly in rural cotton plantations.

This new generation of men were mostly creatures of Atlanta and of the modern times in which they lived. They were businessmen at home in the city, with trains and very soon with motor cars, living in homes and offices lit by electricity, not men who worked by candlelight, clutching a mint julep on a rural cotton plantation as they did their accounts—even if they liked to imagine they were.

The Men Behind George Blackstock

Let’s return to George Blackstock. Most ordinary people are lost to history as individuals. But we know George Blackstock’s name because he was prosecuted for his role in the Massacre. George Blackstock acted after he had become convinced that there was a sudden massive outbreak of sexual assaults by black men on white women in Atlanta. There wasn’t.

But everything Blackstock had been taught to believe as a working-class white Southern man had primed him and the other rioters to believe there was an outbreak of rapes of white women by black men. Note that they didn’t care if white men raped black women, which was very common in part because it was never punished. They believed and wanted to believe that black people were not only inferior, but “bestial”, and a threat to whites, and especially to white women.

Blackstock was just some bloke, some working-class ruffian, wasn’t he? Some racist redneck?

But why did the likes of George Blackstock decide on this date, on September 22, 1906 to take the very drastic step of getting on streetcars, and riding to downtown Atlanta to attack, wound, and even murder random people because they shared the same skin color as alleged anonymous rapists?

Yeah, I understand that “they were racists, duh” seems like an adequate answer, but it absolutely is not. Everyone, every human being, is bigoted against some group—everyone! After a short residence in Wisconsin, I have already fallen into the state prejudice against visitors from Illinois.* But very few of us take our prejudice to the level of ganging up to go assault, maim, and murder. These men did, and they did it in one particular city, and on one particular day. Why?

*The Wisconsin nickname for Illinois people is FIBs. It stands for “Fucking Illinois Bastards.”

This sort of explosion of anti-black hate surely had nothing to do with the white commercial-civic elite, did it? Nothing to do with the gentlemen steering Atlanta into a progressive future, surely? That’s what the elite wanted us all to think, then and now.

Mostly, hideous examples of racist violence in 19th and 20th century Georgia were blamed on riff-raff, who allegedly did all the beating and torturing and murdering while posh white men wrung their hands or were absent. Yet, in Georgia, many families have gone to great lengths in the past century to cover up their elite ancestors’ involvement in atrocities, rather than coming clean. Don’t for a moment buy into the lie that Atlanta’s poshest poshoes weren’t involved in lynchings, including the Massacre. Indeed, they were very involved, as Dr. Mixon shows, even when they were nowhere to be seen.

The Commercial-Civic Elite who ran Atlanta was dominated by the richest men who wore several hats: Businessmen. Lawyers. Politicians. And most of all, they were newspaper owners. Owning newspapers, controlling the media of the day, gave the tiny group of the wealthiest leaders of the city’s Commercial-Civic Elite massive power over white public opinion in Atlanta, including the opinions of men like George Blackstock. This control of public opinion, in turn, helped these wealthiest members of the elite pursue personal power, over Atlanta, and all of Georgia.

Let’s Take a Closer Look at Their Goals

“The Atlanta riot was part of a regionwide effort to make blacks politically vulnerable, and then to terminate their access to power."

Gregory Mixon, author, The Atlanta Riot

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre wasn’t just a bunch of working-class whites rioting, assaulting and murdering. It wasn’t actually led by men who could easily be dismissed as “trash”. The Massacre wasn’t just an expression of hate, although it was certainly that. And it was not a spontaneous event that could have happened anywhere, anytime. It happened in Atlanta, on September 22, 1906, and there are reasons for that. Historians look small to see large.

The Massacre happened because the most elite white men in Atlanta—in Georgia—were fighting for power, sometimes in alliance, and sometimes against each other. Their goals were personal, and also tapped into a broad movement among elite whites in the South to take back all power from the people—black people, and also other white people.

Some background: After the Civil War ended in 1865, Reconstruction began, This was the US federal government’s postwar program to rehab the defeated South, to promote democracy, and to give black Southerners economic and social justice. It also benefited poor whites, bringing public education to the South for the first time. But Reconstruction had been controversial—some Northern politicians were more enthusiastic about it than others— and it was ended in 1877. By 1906, the white Southern elite was pushing toward totally killing off Reconstruction’s gains. They planned to do this by removing all power from black people, and returning all power to elite white men—to themselves.

To succeed, however, elite whites needed to avoid drawing attention and possibly more military intervention in Georgia from the US federal government. They needed to be careful not to turn off wealthy Northern investors who brought money to Atlanta, and who wanted to believe the fiction that the white South had learned its lesson. To accomplish this goal. ordinary white men were needed to be the foot soldiers, the patsies, the scapegoats. Men like George Blackstock.

What Happens in Wilmington Doesn’t Stay in Wilmington

The Atlanta Massacre of 1906 was not the first event of its kind in the postwar South. It drew inspiration from a similar event in the small city of Wilmington, North Carolina just a few years earlier, in 1898.

The Wilmington Massacre or Coup happened in the aftermath of America’s first Great Depression—no, not the one with Herbert Hoover and FDR, which was actually the second Great Depression. No wonder we’re confused: Unlike THE Great Depression, which is what it says on the tin, as Brits say, we call the first Depression the Panic of 1893. That’s actually the name of the financial crisis that set it off. Calling it that just makes it sound like Americans were running around like headless chickens for a few minutes. In fact, the Panic itself set off this first Depression, which lasted about four years, until 1897. And in the 1890s, unlike the 1930s, the federal government seemed unable or unwilling to fix things for ordinary Americans.

Many ordinary Americans in the 1890s found themselves abandoned when the economy tanked, including the rural majority. The government’s response was pathetic, so people turned to populist political movements. White and Black Americans, both, were drawn to populism. In Wilmington, North Carolina, white farmers and black voters democratically elected a local government aiming for the good of the people. Yeah, populism is not by definition led by grifters for grifters.

However, elite white men in Wilmington, North Carolina, were unhappy with this turn in local politics. So they plotted. In 1898, as the national and local economy recovered, they encouraged and led ordinary whites in literally driving out this democratically-elected local government with violence.

How did they get ordinary people to overthrow a government democratically elected by, for, and of ordinary people? Easy: The elite stirred up ordinary Wilmington whites’ resentment against successful local black people. The resulting mob killed black citizens, destroyed black businesses, and restored to power the elite in the form of the local Democratic Party, which was the party of the white supremacist South.*

*NO, NOT THE DEMOCRATS NOW—Or the Republicans now, for that matter. For anyone to claim that we should expect the modern Republican and Democratic Parties to somehow be the same people, to have stuck to the same values of their 19th century versions, truly blows my mind. Hellllllllo? Things change? Not the same cast of characters at all. Oy.

The Wilmington Riot was big national news in 1898. You bet the Atlanta Commercial-Civic Elite, the white men who ran Atlanta, and who wanted tighter control of the city, and who wanted black Atlantans out of power, or out altogether, were paying very close attention to what happened in North Carolina in 1898. Among them? The wealthiest and most influential men, who had higher ambitions for power over the state of Georgia

Annette’s Aside: During the COVID-induced Great Awokening, loads of white Americans claimed never to have been taught about the Wilmington Race Riot/Massacre/Coup. Maybe you were one of them. But the reality for many Americans, at least those under forty-five, was that they probably just weren’t listening that day, or missed the line in the textbook in the wretched US history survey course that gallops at breakneck speed through one damn thing after another.

Most people learn most of their history as teens, not the best time. And all of us best remember what strikes us as really relevant at the time we’re learning. The rest, we memorize for the test and forget.

The Atlanta Commercial-Civic Elite were an optimistic bunch of city boosters. But they had fears. And the greatest fear of elite white Southerners in 1906 was the fear that drove the Wilmington elite of 1898, and the fear of elite white Southerners all the way back to the 17th century: Ordinary white people and black people joining together to overturn the whole bloody exploitative and corrupt system under which they lived.

Atlanta was not Wilmington. It was bigger, and there was not an integrated Populist city government running things, although members of Atlanta’s Black elite were on some committees. But some in Atlanta’s white elite came to decide by the end of the 19th century that the key to ending the power of blacks and ordinary whites AND achieving their own personal political ambitions, was to do something like the Wilmington elite had done.

They needed to find a way to turn whites against blacks in Atlanta. And they needed to do it without damaging Atlanta’s prosperity, without drawing the attention of the federal government, or turning off Northern investors. Wilmington offered a blueprint: Stirring up ordinary whites against all blacks. Making it seem random, even when it wasn’t.

Didn’t You Say These Leaders were Progressives? I’m confused

I get that this is hard to get our heads around! But yes, I did say that, because it’s true: Many in the new elite were Progressives except on race. And maybe class. And possibly women’s rights.

Progressives often favored extending the vote to women. That was often translated as white women: If black women got the vote, so would black men, and that possibility, white Northern women’s suffragists worried, might stop white women getting the vote.

In fact, Georgia would be one of the last states to give white women the vote. Elite Progressives in Georgia were more interested in taking away votes, specifically from black men, and in resurrecting elite white male rule, which, by the way, included rule over elite white women.

Note that word “elite”. White Georgians would not become equal to each other in the Progressives’ vision. However, elite white Georgians needed ordinary whites to support their power grabs. How would they get that help? One way: Make poorer white men feel that posh men were their comrades, although not enough that they would try to invite themselves to dinner.

In the Georgia envisioned by this new elite, the “best men” as they called each other in their own newspapers, ordinary whites would not be invited to mingle with the rich on equal terms. But they would be reminded to feel superior to all black people. The implication was that they would be free to terrify, intimidate, physically assault, and, yes, murder black people, to get them out of public spaces in cities: Schools, parks, sidewalks, streetcars, everywhere.

But that presented another problem for the elite. In their eyes, the power to control Black people should be theirs alone, not exercised by mobs of white riff-raff. That’s what made encouraging the Atlanta Massacre a very risky move: It gave ordinary white men that kind of power. So the elite allowed them that power just for a moment, and then took it away. That’s why George Blackstock was prosecuted.

Who were the men behind the Atlanta Massacre? Let's meet some of them in Part 2:

Not a Nonnie yet? Join us here at Non-Boring History as a paying subscriber for the complete picture, and so many exclusive benefits, including my read-aloud of this post in my English-Scottish-American accent.