Hate's Modern Masters 2

ANNETTE TELLS TALES The progressive men behind the racist Atlanta Massacre

Note from Annette

If you're a Nonnie (a paying subscriber to Non-Boring History) , note the voiceover link for this post, above. Yes, I recorded the whole thing in one take. 😂 Don't ask. Just another great perk for Nonnies, the readers without whom my work can't happen.* Join us today for all the great benefits, including meet-ups (online and in person), no paywalls, the searchable database of fresh NBH posts, actual personal letters from me, and now voiceovers. Details here about annual and monthly memberships (it’s quick and easy).

*This is not my hobby: I am a professional historian (PhD and all that), this is my more-than full-time work, and this series took three weeks of hard graft. If you don’t think I should be paid, then perhaps you could explain to the NBH Accounting Gnome how we can pay the bills.

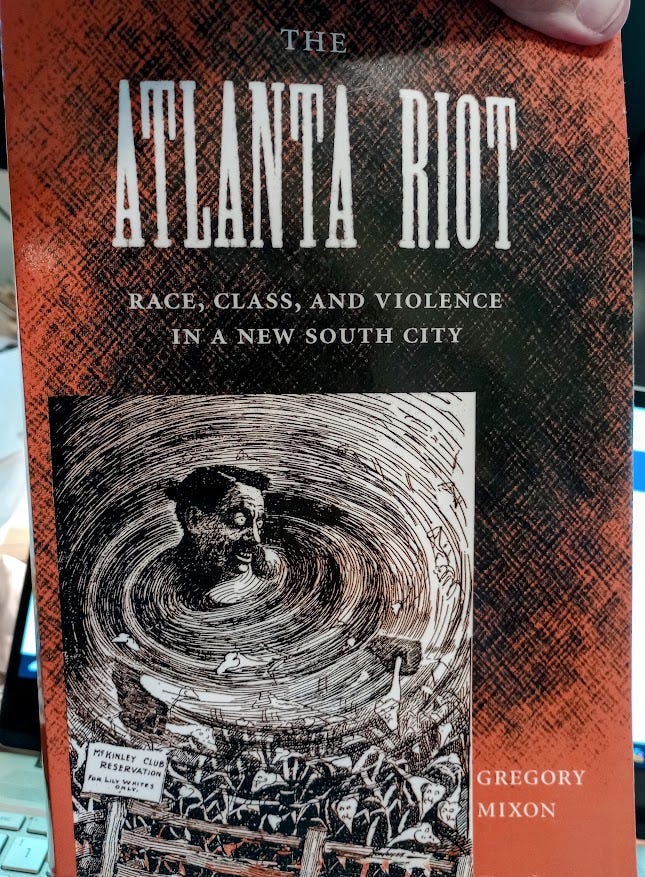

Today, it's Part 2 of Hate’s Modern Masters, my riff on Dr. Gregory Mixon’s The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, and Violence in a New South City (2006)

On September 22, 1906, a mob of white men tore through the modern downtown business district of Atlanta, Georgia, attacking and murdering every black person they spotted.

Dr. Gregory Mixon’s book is about understanding the forces and the men behind the violence, and the devastating impact they had.

I strongly recommend reading Part 1 first:

Hate's Modern Masters 1

The curtain rises on a veritable devil’s cauldron. An atmosphere overhead, usually resplendent with electric lights, blackened by a sheer swirling dust and powdersnake, beneath, the faint glimmer of blue steel, the brandishing of dirks, the dull thud of wielded clubs, the whir of stones, the crash of glass, and the deafening report of guns . . . the dreadful faces of . . . an organized . . . mob.”

Annette

P.S. Yes, again, I know this is unusually long. But I put in a Dukes of Hazzard reference. So there's that.

New Men: The Battle for Georgia

Ruling over early 20th century Atlanta wasn't enough for all the city’s emerging leaders, the white Commercial-Civic Elite. Some wanted power over all Georgia, and even beyond. They wanted to crush the gains and independence of Black people that had happened since the US Civil War. The years before the Atlanta Massacre also saw a growing battle for power among the white elite over which of them would be in charge of their Evil Empire. Sorry. I couldn’t help myself there. These are not men I would care to meet. Running into the Georgians who filled their shoes was bad enough, and while that's only a few Georgians, everyone else in Georgia knows who I mean.

White progressive elite reformers (also described in Part 1) challenged the city and state’s existing leadership, and especially Clark Howell. By 1906, Howell was owner of The Atlanta Constitution, the city’s most influential newspaper, and also considered political “boss” of Georgia. Now he was running for Governor of the state.

In this fight, the reformers —and Howell—were all prepared to weaponize racism, and encourage violence, to reach their political and personal goals.

Let’s take a closer look at them, unpleasant though that is. And let's start with who they were not.

Atlanta’s Commercial-Civic Elite were not the old Georgia slaveowners based on cotton plantations in the countryside. They weren’t even their sons.

The Atlanta white elite in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were mostly Civil War veterans who had been working-class Atlantans before the War, their sons, and ambitious incomers.

These guys wanted to be the heirs to the old slaveowners’ political power. They resented that slavery had ended. They were Southerners, and they had watched angrily as Black Georgians became free, and finally got rights, including the vote.

Atlanta's white elite did not consider Black equality acceptable. And you bet they resented the growing success of the city’s Black elite, in education, politics, and business. The white elite objected to what they called “negro domination”. What did they mean by “negro domination”? Black American men exercising any power or independence, even by voting. They objected to any success among Black people, because that put the lie to racism. In short, they wanted Black people powerless, and limited to working long hours at the worst jobs, or out of the city altogether.

But before the wannabe elite of Atlanta could wage battles against Black Atlantans, they first had to gather up all the wealth they could, because wealth is power. Between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and about 1910, some of these men, the elite of the elite, became very rich from businesses of all kinds. These included railroad development, and especially newspapers, because control of public opinion is power indeed. Ahem. Cough. That’s why Dr. Laing (me) advocates reading a variety of sources, including nonprofit news channels and independent journalists. And books not written to fit today's headlines.

In 1906 Georgia, public opinion could be controlled quite a bit. The US South was a region where public education hadn't existed at all before the Civil War, not even for whites. Then, rich kids were privately educated, often going to colleges in the North.

Something I’ve noticed: The emerging white Atlanta elite, if they had attended universities, seem to have attended Georgia colleges, which were—how to put this?—not as intellectually challenging as the best Northern colleges, and — just a hunch— not as good as the Black colleges emerging in Atlanta, which drew enthusiastic Northern educators.

Hmm.

Working Class in Black and White

White working-class men had far more modest ambitions than the white elite, but their goals were just as important to them.

They wanted better pay, hours, and working condition. They wanted to enjoy their free time. Enjoyment meant the sort of working-class commercial entertainments in which cities specialize: Places to hang out, offering boozing, dancing, and gambling, the kinds of fun things people do when they have hard lives and limited time off. Hey, I'm not going to judge. However, this was the kind of fun at which the elite turned up their noses (unless they were doing it).

But workers wanted and needed a break from always being under someone’s thumb. Working in a city job, like in a factory, with long hours and tight supervision of what they did and when, meant working-class white men had even less power over their lives than they had had in the countryside.

When they changed jobs in protest at pay, hours, and conditions, when they hung out in Black-owned bars and dance halls that offered a good time, when they mingled with black men, white working-class men threatened the power of the white elite. That's because it was super-important to the Atlanta white elite to control everyone, including the white working class. They wanted absolute power.

And working-class black men made the white elite feel even more threatened.

Like white workers, black workers didn’t want to be stuck in crappy jobs with abusive bosses, either. They, too, refused to just tolerate bad jobs with long hours, low wages, unpaid overtime, and jobs that could suddenly end without notice, Challenging white bosses could be very dangerous for black workers. They protested all the same, by taking time off, quitting, and searching the city in search of better gigs.

Annette’s Aside: Sound familiar? At the time Dr. Mixon was writing in the early 2000s, the Great Resignation of the COVID era was far in the future. He did not have a crystal ball. No historian does. Cool, huh? And by the way, the same arguments were made more than a century ago: People who refused to work for inadequate wages and lousy working conditions (like taking a long bus ride to work, only to be told you aren’t needed that day) were accused of being lazy. Especially if they were Black.

White working-class men in Atlanta surely would have tried to unite with black men for better pay, hours, and working conditions, right? That possibility was certainly present. Working-class men, white and black, encountered each other together in Atlanta’s black-owned bars and dance halls on Decatur Street.

But black and white workers uniting politically didn’t happen, thanks to racism having done its job. Black and white working-class men often competed for the same work in Atlanta. Whites had been trained to see Georgia as made up of two bitterly rival racial teams, like college football only more so, not as individual working people who shared concerns.

Raised in racism, white men agreed with accusations that blacks were “lazy” when they quit their jobs. And working-class whites in the city were also angry to realize that elite black people were earning much more money than they were. They saw well-dressed Black people in downtown Atlanta who could afford nice clothes and streetcar fares, when there were white workers who could not. White workingmen found this especially galling because they'd been raised to believe that all whites were automatically superior to all blacks.

And black and white working people uniting didn’t happen because, by 1906, the white Civic-Commercial Elite had worked for more than a decade to prevent such a thing from happening.

As well as stirring up white working-class racism and resentment through segregation and vicious newspaper articles, Atlanta’s white Commercial-Civic Elite also tried to plaster over the huge differences in wealth and power, the class differences, between themselves and white working class people. A single (but far from equal) Team White People was the new white elite’s goal.

That said, it’s fair to say that the Atlanta elite did have one important thing in common with ordinary white Atlantans: They hated black people, too. Racism wasn’t just an act to get power: The white elite of 1906 really hated elite black Atlantans.

I mean, W.E.B. Du Bois (PhD Harvard) the learned and intellectually intimidating professor at Atlanta University, alone must have scared the bejeezus out of the white elite.

But the white elite had it in for all Black Atlantans. By living independent lives in the city, even the poorest black people threatened the white elite’s rights, threatened their identity as elite white men, to control everyone, and everything, absolutely.

Who Are These People? Naming the White Elite

Let’s take a closer look at the wealthiest of white men who dominated what Dr. Mixon calls Atlanta’s Commercial-Civic Elite, or as I learned to call powerful people when I lived in Georgia, Good Old Boys (GOBs) (although some of them are girls these days).

The leading. members of the 1906 Atlanta elite were a shockingly small and — this is honestly my take —utterly mediocre group of men who formed alliances to grab power, and then took turns appointing each other—and helping to get each other elected- in powerful positions.

Let’s start with the OG (original) Atlanta GOB himself, Henry W. Grady, the inventor of the New South. Even though he died long before 1906, a lot of what happened in that year, including the Massacre, can be traced right back to him.

The Cold Dead Hand of Henry Grady

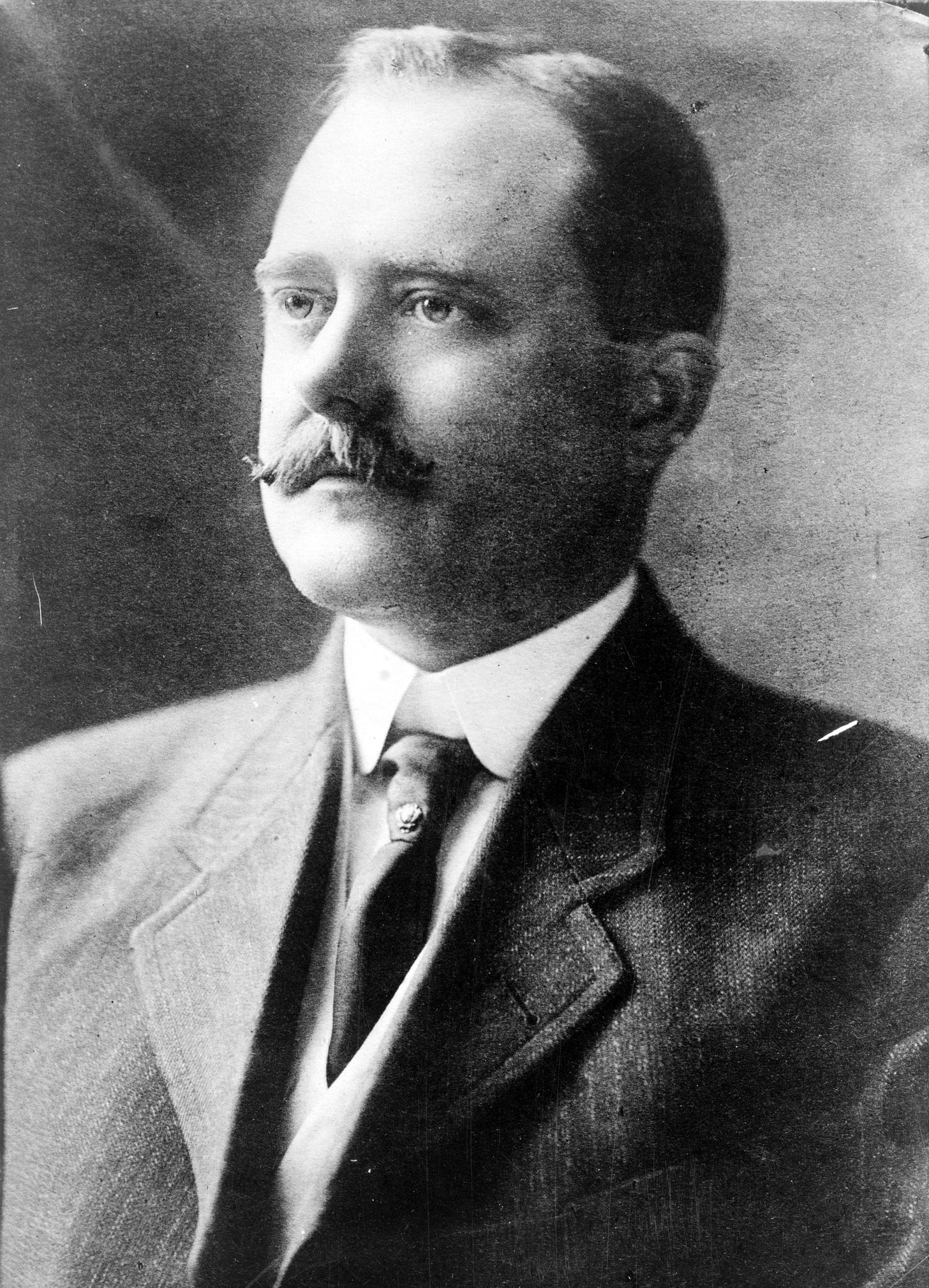

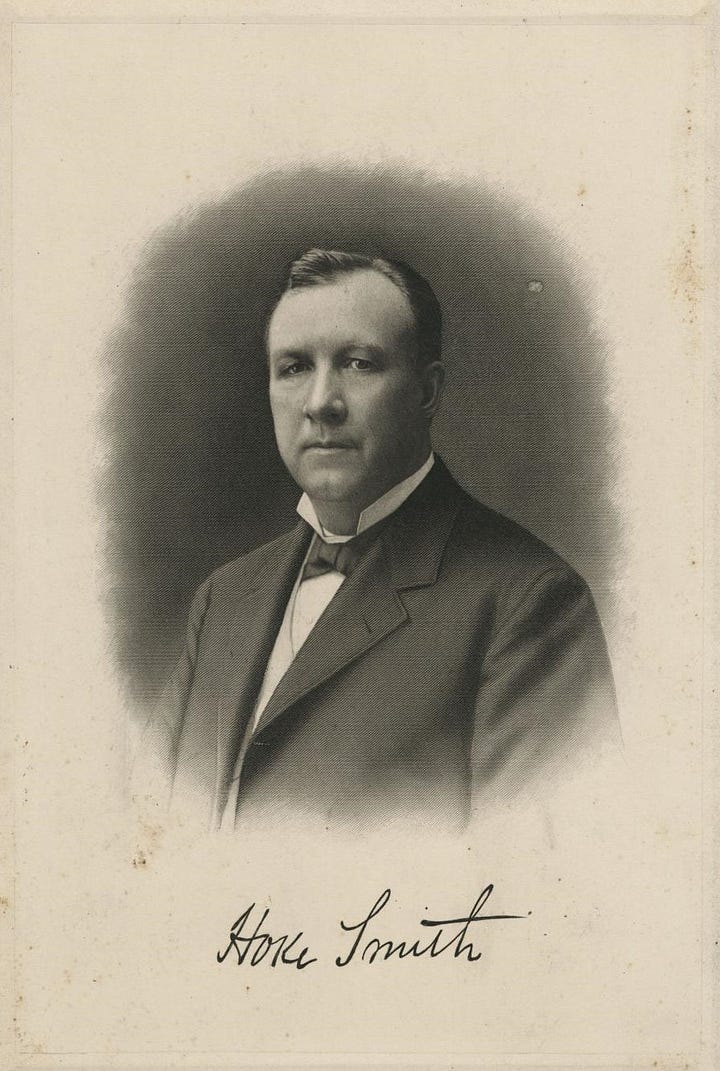

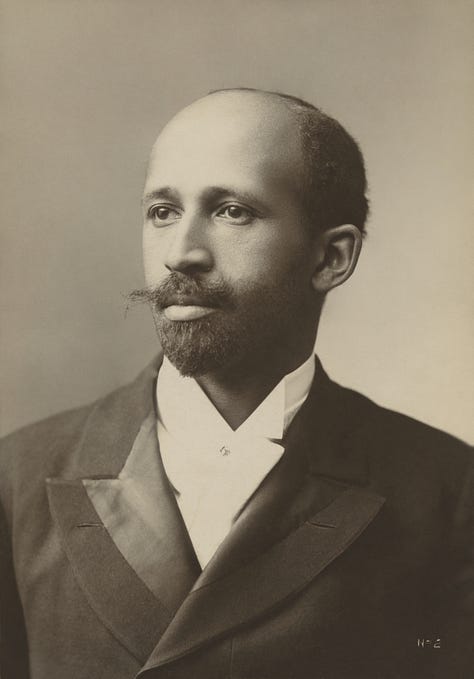

You can see Henry Grady’s photo at the top of the post. Throughout the 1880s, he was the influential and increasingly wealthy editor of the Atlanta Constitution, the city's big daily newspaper, a role that gave him enormous power and influence.

Henry W. Grady was a graduate of the University of Georgia and an ambitious young Atlanta journalist who quickly became part-owner of a small Atlanta newspaper. In an editorial in his paper, 24 year old Grady invented the idea of the New South, a region based not on wealth from cotton, but on cities, with money pouring in from railroads, businesses, and industry. He envisioned Atlanta as the largest, most prosperous city of all.

Grady’s New South article earned him attention from Evan Howell, the editor and part-owner of The Atlanta Constitution newspaper. Howell invited Grady to became a part-owner and managing editor of the Constitution. He also made Grady a member of the Atlanta Ring, the first clique of GOBs in the city. Soon, Grady traveled to promote Atlanta, speaking to Northern investors, and became leader of the Atlanta Ring.

Even as he gave speeches in Northern states claiming that slavery was dead, and that Northern investment (hint! hint!) could help launch the rebranded New South, Grady used the Atlanta Constitution to push white supremacy. He endorsed lynching, a form of violent terrorism meant to intimidate Black people. Grady’s newspaper tried to make lynching sound like a bit of harmless fun, like bowling, even as it reported lynchings in grotesquely sadistic accounts.

Grady’s vision for Atlanta was all white. Only white people would benefit from the prosperity he promoted, In his vision, no matter how mediocre white men might be, they would not have to compete with Black people. And he controlled public opinion among his white readers: With his newspaper as his loudspeaker, Henry Grady had huge influence and power over Georgia politics.

So Henry W. Grady is important to our story, even though he died, aged just 39, seventeen years before the 1906 Atlanta Massacre. That’s because he continued to cast a long shadow. I actually mean that literally: Black people fleeing the mob on the night of September 22, 1906, tried to hide in the darkness beside Atlanta’s massive statue of Henry Grady on Peachtree Street. The corpses of black victims were dumped at his feet.

Bastard Sons of Henry Grady

Henry W. Grady’s vision of a New South, his newspaper-led campaign for a prosperous modern Atlanta under the control of elite businessmen like him also cast a long shadow through the men he mentored and influenced. Henry Grady’s political proteges (mentees, if you insist, but I hate that word) were Hoke Smith and Clark Howell. Yes, Clark was the real son of Evan Howell, the guy who brought Grady to power in the first place, and the mentored “son” of Henry Grady.

Annette’s Aside: By coincidence (I think!), I just wrote about a family history of historian mentoring and my place in it in this post.

I don’t like to load you down with names, but Clark Howell and Hoke Smith became two of the three key GOB players in the Massacre story.

I’ll also mention Thomas Hardwick and James R. Gray, who were closely involved, but you’ll hear less about them, so no worries about remembering those names.

Let's meet Clark Howell, Henry W. Grady’s #1 protege, who, after Grady’s death, became the establishment leader from whom the others wanted to grab power, especially his jealous “sibling” Hoke Smith,

Wait, my Atlanta readers are saying, is that the same Clark Howell as the highway? Yup. Almost nobody who drives in Atlanta today has a clue who Clark Howell was. A lot of native Georgians have heard of Henry W. Grady, but were taught about him at school as the Great Man who built Atlanta and the New South.

And it shows. During the Great Awokening during COVID, protestors who knew exactly who and what Henry W. Grady was demanded that his statue in downtown Atlanta be pulled down and put in a museum. The Georgia legislature responded in a very Georgia way: They passed a law in 2022 declaring statue removal illegal.

So without meaning to announce to the world “Why yes, Georgia is indeed the pathetic racist hellhole of your imagination”, that’s exactly the message they did send, and especially to people who do know who Henry W. Grady was. Slow handclap, Georgia Legislature. In soccer, it's called an own goal.

Mind you, I would rather keep the Grady statue and just stick a truly informative info panel next to it, letting the statue stand as testimony to a scary past. So there’s that. Meanwhile, know that Henry W. Grady set the tone for what happened after his early death.

Clark Howell, Big Boss Man of All Georgia, v. the Gang of Four

As 1906 began, journalist and politician Clark Howell was the most powerful man in Atlanta and the whole state of Georgia.

He had long before succeeded his mentor, Henry Grady, and his father, Evan Howell, as sole owner and editor in chief of The Atlanta Constitution, the city’s most important newspaper.

Clark Howell was now also a senator in the Georgia legislature, and head (or boss) of the state’s Democratic Party, by far the biggest political party in Georgia. In short, Clark Howell was the most powerful man in Georgia.

By the end of 1906, things had changed. Henry Grady’s other protege and Howell's fierce rival, Hoke Smith, had stolen Howell’s crown. The two men had battled to become Governor of Georgia, and Smith had won.

Such facts may seem a bit boring, but they’re deeply important to why the Atlanta Massacre happened, why more than thirty Atlantans died, why thousands were traumatized, and why Atlanta is the mess it is today. Yeah, sorry, not sorry. I lived there for the seven longest years of my life. M-E-S-S. Mess.

To get Clark Howell out of power, and himself in his place, Hoke Smith had allied with Thomas Hardwick, James Gray, and most important of all, Tom Watson (don’t panic, I’m getting to him). They all had political ambitions of their own. I call them the Gang of Four. That’s my phrase, not Dr. Mixon’s, so please don’t blame him.

The Gang of Four were rivals, frenemies, who shared several goals:

They wanted to push Georgia into a new, prosperous 20th century and make a lot of money doing it.

They wanted Clark Howell out of power, claiming that political bosses like Clark Howell were bad for Georgia.

And, of course, they wanted to be Georgia’s new political bosses.

Well before 1906, Clark Howell, and the Gang of Four were more than willing to use racism in pursuit of personal power.

Annette’s Aside: Yeah, sometimes it really is that petty and pitiful. Abso-bloody-lutely pathetic, as Brits like to say. Sad, sad boring little men who did enormous harm to everyone else, men and women, white, and especially, black Georgians so they could feel important. Not that I have views.

But of course I have views! I came to Georgia in good faith, and lived there a very long time, and although I was hired by my university to teach early American history, it wasn’t long before I began to think “OMG, where am I?” and started reading modern Southern history. I had thought I knew quite a bit before I got there. I began to realize I knew nothing.

Even then, it took awhile, for reasons I’ll be happy to explain in my Behind the Scenes post coming on Saturday (for Nonnies, paying subscribers.) You know the vast, vast majority of my readers don't contribute a dime, right? Nope. Not kind. Not sustainable. Look, it’s $5-6 a month. If you don’t hesitate to buy a coffee at that price, what’s the big deal? Here you go. Let’s fix it:

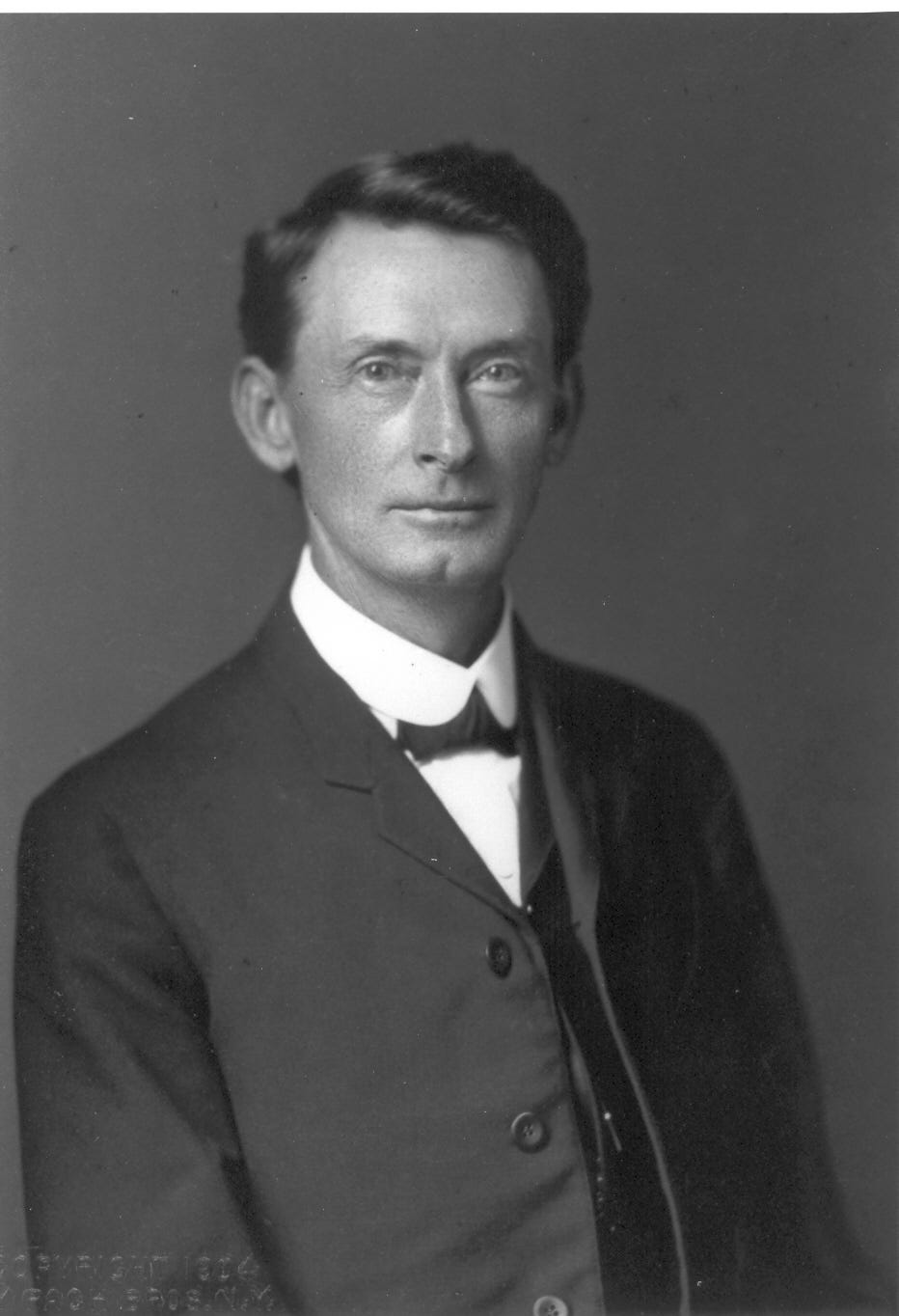

Becoming the (white) People’s Boss: Hoke Smith

“We will control the Negro peacefully if we can, but with guns if we must.”

Georgia politician Hoke Smith, speaking in summer, 1906

By the time the Massacre happened, Hoke Smith was Georgia’s Governor-Elect in everything but name. That’s because he had already beaten Clark Howell in the Georgia Democratic Party’s “white primary”, in which only white voters could participate. Because white voters far outnumbered black voters in Georgia, and the vast majority of whites voted for Democrats. that meant the general election was gonna be a cinch, Yes, Hoke Smith was now as good as elected.

This was a surprise all the same, because Hoke Smith had spent a decade in the political wilderness. Now he was back in a big way: As Governor of Georgia. He had stopped at nothing to get there.

Born in 1855, Michael Hoke Smith was not quite who you might have guessed. Yes, he was born and raised in the South. Yes, his mum was the daughter of a North Carolina plantation slaveowner elite family (a real-life Scarlett O’Hara). But Hoke Smith's dad was a New England college professor who taught at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, until he got fired, and the family moved to Atlanta, so dad could get a job teaching in public school.

So Hoke Smith grew up in Georgia. He became a lawyer, an ambulance chaser a personal injury attorney, making a fortune representing employees and passengers who were victims of railroad companies’ casual attitude toward safety.

In Atlanta, Hoke Smith was ideally placed to profit from the city’s role as a major transportation hub, what with gazillions of trains passing through the city. Meanwhile, as Smith grew richer, he got noticed. He became Henry W. Grady’s political protege, although Clark Howell remained #1 son.

Since Hoke Smith didn't stand to inherit The Atlanta Constitution from Grady.(Howell got that, of course) he instead invested $10,000 of his fortune from his law practice in buying his own newspaper, The Atlanta Journal. Within a few years, he had turned the Journal into the Atlanta Constitution’s biggest rival.

Hoke Smith used his newspaper to push his political ambitions. In the Journal, Smith adopted Georgia Democrats’ racist language and ideas, and used them to try to unseat Clark Howell as boss of Georgia.

But Smith’s ambitions went well beyond Atlanta, and even beyond Georgia. He aimed for power and influence on the national stage. However, in 1896, he messed up. He backed the wrong horse, when he supported William Jennings Bryan, US presidential candidate for the Populist Party, and Bryan’s Georgian running mate for VP, Tom Watson, who was Smith's frenemy, ally, and rival.

After that election disaster, Hoke Smith turned away from politics, and returned his attention to his businesses in Atlanta. In 1903, he built the state-of-the-art Piedmont Hotel, which would serve as a backdrop for some of the most horrific events in the Atlanta Massacre.

To show the public how modern the Piedmont Hotel was, Smith hired only white people as chambermaids and bellhops (luggage porters), just like hotels in the North. This was one indication of the role he saw for black people in Atlanta’s future: Only present in the very lowliest jobs that whites wouldn’t take. Like other white Progressives in Atlanta, Hoke Smith saw this as progress.

By the time of the Atlanta Massacre, Smith had defeated Clark Howell to become Governor and Boss Man in Georgia. In the process, both men had done much to make the Atlanta Massacre happen. More about that, shortly. First, let’s meet Tom Watson.

The Two Faces of Tom Watson

Like Hoke Smith, Tom Watson was a Georgia lawyer, a politician, and a publisher. Unlike Hoke Smith, he wasn’t typical of the Atlanta Commercial-Civic Elite. His political base was not in the city, but in rural areas. He was the son of a pro-Confederacy plantation family who owned slaves, and who lost everything after the Civil War. At first, Tom Watson had joined the Democratic Party like all other white politicians: He was elected to the Georgia legislature back in 1882, with some help from black voters.

But Tom Watson shocked the Georgia elite by joining the Populist Party in 1890. To get elected to the US Congress, he embraced the cause of ordinary rural people, including black people. He promised his black supporters that he would address their concerns, like the awful convict leasing system. This was a horrendous official scam, in which mostly black people were arrested for whatever, and rented for cheap as temporary slaves in everything but name to businessmen who had no investment in them—hey, they could always get a replacement convict!—and so often worked them to death.

Watson and the Populists promised more to black voters than they delivered. When the Populists gained control of the Georgia state legislature in the early 1890s, they promptly passed Georgia’s first laws segregating public transport. But Watson always made sure to put black people on the stage with him at his political rallies.

Meanwhile, Georgia Democrats, threatened by the rise of the Populists, and (just my hunch) likely offended by Tom Watson’s disloyalty to Team White People, worked to get Watson out of Congress, by using voter fraud and intimidating black men who tried to vote. Not surprisingly, Watson lost re-election in 1892. He tried again in 1894, and lost again for the same reason.

Yet by 1896, Tom Watson was not only back in politics, but nationally famous as running mate to William Jennings Bryan in the Populist campaign for the US presidency. This was a great time for Watson’s populist message: The nation was deep in its first-ever Depression (the so-called “Panic of 1893”) Ordinary people in the countryside were looking for men to represent them, as they blamed corporate interests in America’s growing cities for the economic mess.

Bryan lost to William McKinley, who later went on to champion culture wars causes dear to rural people’s hearts. like the prohibition of alcohol, and opposing evolution.

A bitter Tom Watson, meanwhile, had decided that his future lay in taking away votes from black Georgians. So he returned to Georgia state politics, and adopted rabid racism as his new calling card. He started demanding that black men lose their right to vote.

By 1902, Tom Watson also had a low opinion of the white working class as voters. In a letter to a friend, he wondered if what Dr. Mixon paraphrases as “the eager and easily manipulated lower classes” were, in Watson’s own words, “the real evil.”

So well before 1906, Tom Watson, while he still thought farmers were great Americans, had turned against all black and poor white voters. He thought they were all fools, easily manipulated by wealthy white politicians. He claimed that Wall Street investors and bankers were using black voters and what he called “white trash” voters against the farmers. He came to think that only well-off and educated white Southerners should be allowed to vote—so, not even most farmers.

None of this stopped Tom Watson from himself manipulating white voters to get power. He was happy to help convince ordinary whites to hate black Georgians for his own political goals, and the goals of Hoke Smith, and their less prominent allies, Thomas Hardwick and James Gray (sorry, these guys do keep popping up, don’t they? Think of them as people with mostly non-speaking parts in this play).

By 1905, the Gang of Four aimed to knock out Clark Howell as “boss” of politics in Georgia.

Yes, these men were all wannabe Boss Hawgs off Dukes of Hazzard, only less silly! They wanted control not just of the fictional Hazzard County, but of the entire state of Georgia. Both Smith and Watson had their own publications to boost their racist messages: Smith had the Atlanta Journal, and Tom Watson had his own national magazine called, um, Tom Watson’s Magazine.

The battle between Smith and Watson to succeed Clark Howell as Georgia boss escalated in late 1906, after the Massacre. Before they could be rivals, though, Smith and Watson were allies. Think of them as frenemies. And by 1905, they saw how they could use anti-black hate to get Clark Howell out of power, and Hoke Smith into the Georgia Governor’s office.

By 1905, Tom Watson, in his national magazine, was promoting a “people’s revolution” for whites only, a rebellion against black people leading independent lives.

When leading Black clergyman Henry McNeal Turner pointed to the strides that black Georgians had made in education and wealth, Watson shot back that they had only made progress because of white “charity”, through bank loans and philanthropy. Blacks getting the same opportunities as white people was, in Watson’s argument, only happening at all because whites were nice enough to give them those opportunities. Blacks like Turner were “ungrateful” for claiming that they played any part in their own success.

Tom Watson now shamelessly led his national audience into his racist Georgia fantasy, claiming that black federal officials in America’s big cities used their power for sex, and kept white women as sex slaves. In Georgia, these were fighting words: White Southern men had been taught to believe, wanted to believe that black people and white women were properly the property of white men. And that black men abusing white women, who supposedly had the protection of their men, was an attack on the honor of those white men, who had the right and the duty to retaliate, with violence. I think you see where this was going.

The idea of white men as those most harmed by attacks on white women seems bizarre to us. But not to white men in the early 20th century South. Tom Watson defended the honor of white men by slamming Northern critics for objecting to lynching. Let me mention here that typical lynchings at this time were even worse than most people imagine: They went well beyond Black people being hanged in the woods without trial. Lynchings were often large public parties, to which whites brought popcorn and their children, to witness a fellow human enduring death by slow torture. And Georgia was the capital of Southern lynching.

Many of those lynched were black men, accused (practically always falsely accused, and yes there’s evidence) of raping white women. Watson argued to his readers that Northern critics should not waste their time sympathizing with lynching victims, or even women rape victims, but instead should consider the feelings of the male relatives of the white Southern women who had allegedly been raped.

These white men, Watson argued, stood ready to commit violence for their womenfolk, who needed constant protection. Talk about the power of suggestion: His readers around the country were paying close attention, and his white readers in the South were already primed to believe it.

And anyway, Watson suggested, ALL black Southerners—elite and working-class— provoked white violence whenever they treated any whites as their equals. How very dare they!

So, to sum up, this was Tom Watson’s message: Black men accused of raping white women deserve to be assaulted, tortured, and murdered. Oh, and black men are uppity in general, and whatever happens to them is their fault for not accepting their lowly place in life. And, Watson claimed (falsely), black writers like Max Barber [see part 1] promoted anti-white hatred, presumably by objecting to dreadful things that white people actually did.

This is what psychologists call projection. Tom Watson was accusing Max Barber of what he was actually guilty of himself: Racism. And Tom Watson argued, in another bit of projection, and with memories of the first version of the Ku Klux Klan still very fresh, that whites needed to unite against black self-help organizations. These harmless clubs were the kind that help widows and orphans. Watson labeled them sinister “secret societies” , which is actually a spot-on description of the terrorist Ku Klux Klan of the post-Civil War period. Black societies, Watson implied, were plotting against white people. He even imagined black Atlantans planning to kill whites in retaliation for lynching. These spectacular claims were all projection: Black people were busy getting on with their lives and pursuing their goals as best they could despite the terrorism of lynching and Jim Crow. Nobody sane wanted to risk a nasty death by attacking whites.

But that truth didn’t matter to Tom Watson. He had figured out that, by supporting Hoke Smith’s run for governor, he himself had a real chance to be Boss of Georgia. Pretty ironic ambition for a man who once claimed to be a representative of ordinary people, and who had once courted black votes.

Moving to Massacre: 1905-6

DING! DING! In 1905, it was time for the showdown between Hoke Smith and his archrival. Clark Howell, when both men ran for Governor of Georgia. They pushed their campaigns in their respective newspapers, the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution. And they did so by spurring white men to hate black people

Hoke Smith was as much a city guy as Clark Howell, his opponent. But with Tom Watson in his corner, Smith aimed to use racist anger to stir up white working-class voters in rural areas as well as Atlanta, to vote for him. He dreamed of the Georgia Governorship propelling him to a national leadership role as a Progressive. His progressive vision just happened to include crushing black people.

The race between Smith and Howell was tight. In their newspapers, and in their political speeches, the two candidates didn't hesitate to use racism to rile up working-class white voters. They both proposed taking votes away from black people. They accused black Georgians of being ungrateful economic failures, “savages” incapable of contributing to the New South, and unsuitable for any social contact with whites. Both candidates also made false allegations that black men were raping white women.

In short, both Howell and Smith, who was aided by Tom Watson writing in Tom Watson’s Magazine, provided a widely-read rationale for the Massacre in their publications, two of which were Atlanta’s biggest newspapers, and the other a magazine with a national readership.

The Atlanta Massacre wasn’t a spontaneous event. And by the time Hoke Smith won the election for Governor of Georgia, by the time he and Clark Howell had finished a brutal campaign dedicated to stirring up white anger and violence against black people, the Atlanta Massacre had happened.

It wasn’t just Smith and Howell, either. Their words were not even the most racist language used during the campaign. The entire Atlanta Commercial-Civic Elite, the white men who ran the city, and smaller newspapers eager to stir the pot, were right behind them.

But theirs were not the only public voices in town.

The Black Atlanta Elite

Black people saw opportunity in Atlanta, and among them was an emerging Black Elite. They did not share the racism of their white counterparts. That said, they didn't lack sexism or patronizing classism, because they lived in a time of great economic inequality, and an age when masculinity (manliness, it was called) was a big theme in the US*

*UK readers: Also in Britain: Think Rudyard Kipling and Robert Baden-Powell, who founded the Boy Scouts in 1907, the year after the Atlanta Massacre. Canadians, you got Scouting later, because of course you did, but the Girl Guides were founded first (1910) with the Boy Scouts turning up in 1917.

Many of the black Atlanta elite were highly-educated men with no personal memory of slavery. Let’s start with a Big Name.

Nobody in Europe had heard of Hoke Smith or Clark Howell, but many people around the world knew of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois. A Harvard-educated Northerner from a long-free family in Massachusetts, Du Bois was a professor at Atlanta University, the first Black college founded in the South. He argued there was a “talented tenth” of black people, of whom he was one, of course, which is a bit elitist. However, he also believed, like others in the Black elite, that he had a responsibility to “uplift” the other 90% of Black Americans.

Max Barber, who we met in Part 1, was born free to two former slaves in South Carolina, and his writing made him a major influence via his own magazine The Negro Voice, and other publications.

John Hope, the first Black president of Atlanta Baptist College, later to be known as Morehouse College, was the son of a free black woman in Augusta, Georgia, and her common-law husband, a white Scottish businessman (from Langholm, in the Borders) (you know I’m thrilled about this) Despite laws forbidding them to marry, they lived together as husband and wife.

Black Atlanta’s elite included not only educated leaders like Du Bois, Barber, and Hope, but practical businessmen, most notably the wealthy barbershop owner and, starting in 1905, insurance company owner Alonzo Herndon. He was the formerly enslaved son of an enslaved mother and a slaveowner father. By 1906, he was employing black barbers to cut the hair of rich white guys in three luxury barbershops, while starting to serve black customers (and their interests) via his insurance company, which would prove wildly successful.

All three men, and others, were ambitious to share power with Atlanta's white elite, men whom they considered their partners in social class. At the same time, they also wanted to help ordinary black people to become property owners and full citizens.

This was not exactly what conservative Black educator Booker T. Washington had promoted back in 1895. In his Atlanta Compromise speech, Washington assured his white audience that blacks would not seek political and social equality with whites, so long as they could make a living. Booker T. Washington did not speak for Barber, Du Bois, Herndon, or John Hope, who said outright that what Black Americans wanted was equality with whites as US citizens, not as second-class citizens.

In Atlanta, as early as the 1880s and 1890s, Black leaders seemed to be making gradual progress toward their goal of acceptance as class partners with white leaders. They were also working to reform working-class blacks—whether they wanted to be reformed or not— to make them more acceptable to white people.

What kind of progress was the Black elite making? In the 1880s, Black leaders like Henry Rucker joined Atlanta’s Committee of One Hundred, an influential group of citizens. These Black leaders were outvoted much of the time, but they did try to reduce discrimination in jobs and public education. They even put together an all-Black slate of candidates for mayor and city council in 1890, all small businessmen, like grocers.

But the gains that Black Georgians had made since the Civil War were under attack by the time of that election in 1890. Elite whites, learning of the all-black electoral slate, came up with a slate of white candidates, and successfully appealed to white working-class voters on the grounds of white solidarity and supremacy. This was a sign of things to come.

Six years later, Henry Rucker and other black Georgian Republicans helped make William McKinley US President. But, by then, 1896, the national Republican Party had lost interest in Black Atlanta, and that made black citizens vulnerable to white violence. Another warning sign, ten years before the Massacre.

Now please don’t think that everyone black in Atlanta had the same vision of what equality meant, and how to get there. The Black Elite had their own plans for Atlanta’s Black working class. John Hope wanted to train clergymen as leaders, to lead working-class blacks to respectable middle-class lives, just as Jane Addams and Ida B. Wells and other settlement house leaders were working for much the same goal among migrants to Northern cities.

Yale-educated Black minister Henry Proctor led a campaign against black dance halls, calling them “cesspools of vice” that encouraged crime.

This sort of thing didn’t please working-class Black Atlantans, but it earned elite whites’ encouragement, and funding for black churches and schools.

Clark Howell praised Proctor in the Atlanta Constitution for his campaign against black dance halls, and for associating them with crime. But while Proctor’s ultimate goal was for blacks to leave off dancing and become respectable property owners, Howell wanted dance halls closed so blacks would stop mingling there on friendly terms with each other and with whites.

Clark Howell wanted working-class blacks to spend all their time on what he insisted was their only proper role in life: Working every waking hour for white people in the lowliest and most miserable jobs, under strict supervision. Just like slavery!

Rev. Henry Proctor, however, wasn’t about to have his concern about black crime used against black people: In a report he co-wrote with Du Bois in 1904, Proctor pointed out that while some black Atlantans had turned to crime, this wasn’t because they were black. He pointed out that other black citizens were building businesses, churches, and educational clubs.

Proctor blamed “historic circumstances, not inherent biological faults” for black crime and for what he saw as working-class immorality. Slavery was gone, but it had disadvantaged people within living memory, including by limiting literacy. And peonage (practically slavery, widely practiced after slavery), convict leasing (ditto), and the lack of the vote to change things were ongoing problems. Anyway, he reported, black crime was decreasing: Indeed, only one man in Atlanta, according to the city’s own statistics, had been arrested for rape in 1904. He was white, and his victim was black.

Such arguments and evidence was not what the white Civic-Commercial elite wanted to hear. Such words fell on deliberately deaf ears.

Georgia’s White Elite avoided engaging in reasoned debate with members of the Black Elite. Why? Simples: They would have lost. This was not a battle they intended to win in a fair fight.

There were other warning signs for Black Atlantans in the lead-up to the Massacre. The Black elite continued to push for more government say-so, especially over their own affairs. Black citizens had donated land for a black public library in Atlanta, because Black people weren’t allowed into city libraries otherwise. Scottish philanthropist Andrew Carnegie had put up the money for the building. Now, Henry Proctor and W.E.B. Du Bois protested that the all-white committee overseeing the building of the library had to include black members.

The Atlanta Constitution now blasted Rev. Proctor and Dr. Du Bois, two highly educated professionals, as if they were rude children, calling them “impudent”. Howell went further, effectively accusing the two men, neither of whom was from Georgia, of being outside agitators. That would later be a common complaint against civil rights protestors in the 1950s and 60s. Du Bois and Proctor were finally appointed to the committee, but only with great reluctance. Look, if Georgia’s white elite really thought the Black elite was inferior, they would not have made it so clear how threatening they found them.

By 1906, Booker T. Washington’s promise that Black people would humbly accept their lot in life was fading fast. In 1905, W.E. B, Du Bois, John Hope, and Max Barber were among the African Americans who gathered in New York, and founded the Niagara Movement, a national Black civil rights organization.

And in February, 1906, just months before the Massacre, black leaders from throughout Georgia met in the city of Macon, south of Atlanta, to demand action on segregation and discrimination:

How did Georgia’s white elite respond to this civil rights conference? They ignored it.

Propaganda and Power: 1905-6

Black and white Atlantans of all classes were involved in building the city that Atlanta had become by 1906. But they pursued goals that were incompatible, until in Dr. Mixon’s words, “violence, race, and class collided.”

That collision ended in the Atlanta Massacre, a mob of ordinary white men attacking all the black people they could. They did this supposedly on behalf of white women, and strongly urged on by the most influential members of the white elite.

More than anything else, accusations that black men had raped white women had the potential to inspire white Georgian men in 1906 to riot and murder. Such accusations were not just an excuse for a riot: The white mob believed such rapes had happened, because that was what they wanted to believe, and what they had been led to believe in the city’s mass media, its newspapers. It was easy to get these men to believe, thanks to what we now call confirmation bias, a tendency to believe evidence that supports what we already think.

Annette’s Aside: Before anyone decides these ordinary white guys in Georgia were just idiots, let me just gently point out that we are all susceptible to confirmation bias. That’s why historians have to go through a rigorous training of six or seven years beyond the BA (and sometimes longer) to help us battle that urge to believe only the evidence that fits our research thesis, our working argument, or, put another way, our human tendency to jump to conclusions based on what we want to think.

But most people, of course, don’t do PhDs in history. Americans take sweeping US history survey classes in elementary school (when they’re too young to fully understand the political history they’re fed). They take them again in high school. And for those who go, they take them in college.

Teaching surveys is a job that college administrators increasingly hand off to cheap labor. But real historians who still teach college US history surveys try to teach students to at least have some humility in the face of evidence. Most often, we do this simply by showing them that the stories they were taught in elementary school (and often in high school) hide a far more complicated story.

The vast majority of the public, college-educated or not, is barraged by propaganda from the media sources of our choice. I am proud of the journos who fight this every single day, but they are few and very underpaid: A rich journo is not a good journo.

Often, the only other context people typically have is to measure what they are told against their own beliefs and experiences. When those don’t line up, they think critically. When they do, they believe what they’re told by authority. So let’s not be too quick to pooh-pooh the ordinary white men of Georgia in 1906.

In 1905-6, the rivalry between Clark Howell and the Gang of Four came to a head when Hoke Smith ran against Clark Howell for Governor. How were Hoke Smith and his allies “Progressive” as they claimed to be? They were Progressives. They shared Progressive ideals, such as increasing government regulation at the state and local levels, and limiting corporate power. This also made these city politicians popular among whites in the countryside, as farmers turned to them after they saw their autonomy and money whittled away by big companies. The Gang of Four, and the entire Commercial-Civic Elite, were Progressives. They were just Progressives who hated black people.

Don't imagine white Southerners were automatically conservative. Just as white Southerners later loved FDR and the New Deal, this Southern white racist version of Progressivism was popular among white Georgians.

In the summer of 1905, a newspaper in Waycross, a small town in rural Georgia, was already pointing this out. White people in Waycross wanted the prohibition of alcohol, which wrecked (white) family life. They weren’t comfortable with (white) child labor that staffed the factories of the New South. They wanted limits to railroad corporations’ power over the farmers whose goods they shipped. They wanted many of the same things that ordinary people, white and black, across America wanted. Except that they also wanted the vote to be taken away from black Georgians.

Before 1905, Clark Howell had not taken a public position on any of these important issues. He was not a Progressive. He was not a reformer. He was the Establishment in Georgia. The boss.

So Howell, as he prepared to run for Governor of Georgia in the summer of 1905, took note. He announced that he was a reformer, too, just like Hoke Smith! And he had much more experience than Hoke Smith!

And Howell wasn’t wrong, at least on race issues: As head of the Georgia Democratic Party, he had supported taking away black Georgians’ votes in the primary, and the implementation of “Jim Crow”, strict racial segregation. His newspaper, the Atlanta Constitution, had called for limiting black votes (and some white votes) in the general election.

By the time the election rolled around the following year, Howell’s and Smith’s commitment to reform came down to one issue: Controlling black Georgians, and whether taking away their votes was the best way to do that.

Howell thought that blacks were controlled enough by the white primary of 1896, and that stripping all blacks of their votes, which Smith proposed to do, would lead to white violence against black people. That, in turn, could lead the federal government to intervene in the state, the last thing elite whites in Georgia wanted.

Clark Howell was pretty sure he would win the race for Governor: As Democratic Party Boss, he already had a lot of power. But to make sure he won, Howell (via his campaign staff) accused Hoke Smith of being a “negro lover”, as they put it in print, although I’m sure they used a less polite word in conversation, and that's certainly how readers read it, and were meant to. “Negro lover” was the most polite version of the most powerful and racist insult the Howell campaign could wield against Smith.

Howell’s campaign also charged that Hoke Smith didn’t want reform for its own sake anyway, but to achieve his own personal career goals. According to Howell’s team, Smith was trying to frighten white voters with black power, to unite them around hating blacks, purely and simply to promote himself.

Laing, I’m having trouble keeping up with this.

Aren’t we all, darlin’? Look, basically, Clark Howell, running against Hoke Smith for Governor of Georgia, was accusing his rival of being inexperienced, personally ambitious, and a secret supporter of black people, while he said Smith was also using anti-black language to advance his own political career, and risking Georgia’s prosperity by inciting white violence against Black people. Why, if it weren’t for Hoke Smith, according to Clark Howell, black and white Georgians were getting along famously!

Howell’s campaign (waged in his own newspaper, remember) also alleged that Hoke Smith’s campaign against corporations would damage the rise of Atlanta and other Georgia cities, and cost jobs, as did Smith's allying with Populist Tom Watson.

But let’s cut the crap: Clark Howell was also doing his part to stir up white anger against black Georgians. He tapped into the white fear of the “Menace of the Educated Negro” (oooh nooo! Nothing damages white racism like figuring out that black people are smart.). He claimed that Smith would use literacy tests to disenfranchise black voters, and that the need to be able to read in order to vote would encourage “every negro in Georgia . . .to get out of the cotton patch and into the negro college.” Okay . . .

Howell then pointed out that the top of every hill in Atlanta was “crowned with vast negro colleges, whose combined endowment from Northern philanthropy far exceeds the total endowment of every white college in Georgia.”

Of course, the big reason educated black people scared elite white Georgians was that elite whites knew, in their heart of hearts, that black people were not their inferiors. Heavens, if we give blacks good public education, they thought, how will dim little Pulverington Gossidge III ever compete with Black boys for a place at the University of Georgia? Oh, right. The University of Georgia and its all-important fraternities (for networking) are strictly for whites only. Phew.

Wait. How will we make sure that after Pulverington III graduates, he won't have to compete with black people’s businesses? Oh my Lord, next thing you know, they’ll be running everything in the state!

Yeah, so now you see how that goes. Went. I meant went. Cough.

This kind of tortured thinking was also how Howell could argue successfully that disenfranchising black voters would hurt working-class white people’s advancement by giving working-class black families a big incentive to educate their sons.

Raising the specter of working-class Black people becoming educated was such a powerful political campaign tool that not only was a college-educated young black man like Max Barber a threat, so was a barber, a messenger boy, or anyone black, really. Any moment now, thanks to Northern philanthropists, and black churches and families, blacks would all be literate and educated! EEK!

And anyway, Howell said, if Smith won and took the vote away from black Georgians, the next thing you knew, the Yankee Army would be marching through Georgia again. Howell proclaimed “This is a white man’s country, and it must be governed by white men.”

The Gang of Four, plus their elite supporters, fought back against Howell’s argument, including in the pages of Smith’s Atlanta Journal, and Tom Watson’s Magazine. Taking the vote from blacks, they argued, would solve, in Dr. Mixon’s words, “all of Georgia’s problems.” They pointed to the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 as evidence, claiming this “revolutionary reform” (i.e. actual war on black people) was a win for all whites in North Carolina.

But Hoke Smith wasn’t content with using racist arguments. He also claimed to support the interests of the white working class.

One Atlanta Journal columnist, called on behalf of his boss, Hoke Smith, for a “spontaneous uprising” of white people (or, as he called them, the people). They would be rebelling against government controlled by corporate interests that allegedly used black votes to stay in power. Smith was leading, he said, “a great revolt against Wall Street”.

Tom Watson’s Magazine sounded much the same note. It portrayed Hoke Smith as part of the national movement of ordinary people toward Progressive reform. This was more than populism! This was revolution! It was a people’s rebellion against “the tyrannical suppression of individuals and classes”!

Hey, reader, would you like some tea? Maybe a British biscuit (cookie)? A nice sit down? Sure you would.

Look, I know it’s a real shock to most of my readers to now read ordinary white Southerners in 1905 being portrayed as American Revolutionaries, or maybe as Communists. Or both. But that’s what makes Gregory Mixon’s The Atlanta Riot so very fascinating.

Tom Watson’s Magazine, which was aimed at angry rural people around the nation, also took aim at city people (white as well as black). Those people who drank too much and got into street fights, and got arrested! Them! The city riff raff who hung out in bars, they were easily controlled by bosses, and they voted. Next thing you know, black people will be running everything in America! What’s happening in Georgia won’t stay in Georgia, mark my words! Actually, those aren’t Tom Watson’s words, but you get the idea. My take: If you lack decency, and have a thirst for power and influence, you do everything you can to get your supporters to be afraid of and hate other people, and to get them to trust you.

Hoke Smith summed it all up when he announced his campaign for Governor in June, 1905. He claimed that “the people” had insisted he run, to save them from the power of corporations, “boss rule” and “negro domination.”

To show how tough he was, Hoke Smith made this racist case to an audience of three thousand people in McIntosh County. This was a predominantly Black rural county near Georgia’s southern border with Florida. This was where black men served as local government officials. This was an audience with a lot of Black people in it. What could possibly go wrong?

In case things went wrong, Smith kept a bag at his feet as he spoke: It contained a gun. Hoke Smith was prepared to take down black power by violence, even all by himself, apparently, and he made sure the press knew about that gun. Meanwhile, his speech must've been quite the Springtime for Hitler moment for his audience.*

*If you don’t get the reference, you need to know about The Producers, a brilliant bit of satire.

In his campaign for Governor, Smith praised the Georgia legislature for disbanding the state’s black volunteer militia companies in 1905. That action meant there were no black militiamen to help protect Black citizens or restore order in Atlanta in September 1906.

Smith told Georgians how Alabama, North Carolina, and Virginia had also ended their black militias, installed a white primary, and disenfranchised black voters, while threatening black people with white violence.

Smith claimed that taking away black votes was necessary because the national Republican Party in 1905-6 had pushed “class legislation” that politically divided rich and ordinary whites in national elections. Members of the Democratic Party elite voted to support corporate interests. That’s what happens, Smith was saying, when whites don’t all vote together around America.

Smith ended up talking less about reform that might benefit ordinary Georgians, and more about the importance of white supremacy in Georgia, and, well, everywhere in the US. Everywhere, really.

Smith was not interested in elite Black Georgians’ arguments for sharing power with the white elite, including in managing working-class blacks. He said, “the wise course is to plant ourselves squarely upon the proposition in Georgia that the Negro is no respect the equal of the white man.”

He preferred uneducated Black people: “the uneducated Negro is a good Negro; he is contented to occupy the natural status of his race, the position of inferiority.”

Uneducated Black people, Smith insisted, were better than “the educated and intelligent Negro, who wants to vote, is a disturbing and threatening influence. We don’t want him down here; let him go North.”

Annette’s Aside: Hoke, let me quote your own words back at you. I bet you were “disturb[ed] and threaten[ed]” by “educated and intelligent” Black people, because they put the lie to your crap that a black person “is in no respect the equal of the white man”.

At the end of the day, Hokey, if I might call you that, this goes beyond racism, a mistaken belief that superficial differences are innate, doesn’t it? It’s hate.

You didn’t really think Black people were inferior to whites, did you? You were just afraid that you, a grifter, did not measure up to the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois. And you know what, sunshine? You were absolutely right. You were a nasty mediocre little man. Or maybe you were just saying what it took to win votes? That, too. That, most of all.

Sorry, but not sorry, readers. In case you haven't figured it out, this is both a professional judgment, and a personal one, and one I worked through in my novels, especially the last in the series. But I'm still angry, and so I should be, because these men have caused so much trouble and misery for all of us.

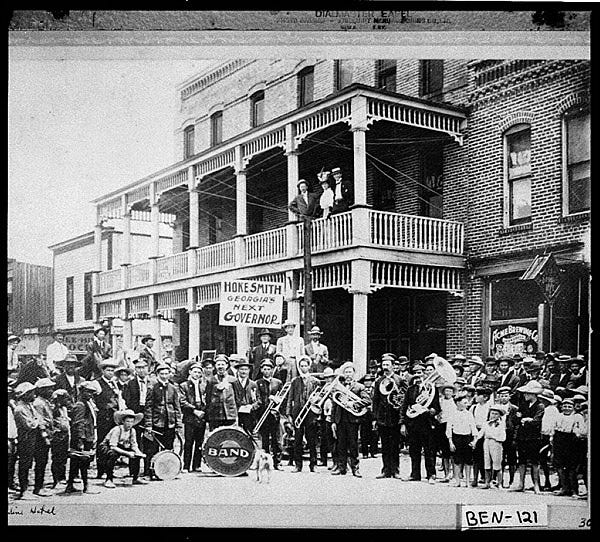

In his commitment to white supremacy (which has a very real meaning, about power and deliberate racism, and should not be thrown around casually), Hoke Smith also went beyond words, to petty actions: While Clark Howell hired a black band in Savannah to play at one of his rallies in rural southeast Georgia, Hoke Smith threw black people out of his rallies, or sent them to sit separately in balconies.

And then, starting in October, 1905, Hoke Smith’s campaign ran a media blitz in the pages of his Atlanta Journal. The paper ran a series of editorials aiming to alert readers to the dangers of not moving fast enough to take away votes from black voters now that the idea was in the air.

The delay gave blacks time to organize, the Journal claimed. After all, this had happened in Baltimore, Smith’s Journal warned, where Black voters, threatened with losing their votes, had formed alliances with Polish and Jewish voters to vote down Black disenfranchisement.

A better model for Georgia, the Journal argued, was Wilmington, North Carolina, where whites in 1898 had used violence to overthrow the integrated local government. According to white North Carolina officials, disenfranchisement had made black people “submissive” and that made them “much better off”, i.e. because white people were less likely to attack and kill them if they pretended to be invisible.

A stable, peaceful society without pesky black people insisting on equality was more likely, the Journal claimed, to attract investment, industry, and jobs!

And there was more! Black people, if they were scared into staying in crappy jobs anyway, would be tempted to return to the plantations to grow cotton, like in the good old days! Yes, according to Hoke Smith’s campaign, white violence brought many, many benefits!

Pretty clear where this was all headed, isn’t it?

Taking the vote from black people, and pure race hatred, were issues that helped bring together whites who hated corporate abuses, like the companies that wouldn’t pay for totally segregated streetcars in Atlanta, and elite men who wanted to take power from Clark Howell, and ordinary city whites like George Blackstock who felt threatened whenever black people—any black people—were more materially successful than he was.

So, to sum up, reformers like Hoke Smith and Tom Watson were determined to take power from black people. They also wanted to take power from ordinary whites like George Blackstock. Indeed, they had already taken away much from the white working class: Through racism and segregation, they had taken from them the rights and the benefits of getting to know people regardless of color or identity, the loss of choices of friends, partners, and even bosses.

George Blackstock didn’t notice his losses, because he now saw his future as one in which his interests were united with those of wealthy powerful whites who he thought cared about him. Honestly, though, they didn’t give a toss about him, except when he did their bidding.

But the George Blackstocks of Georgia were persuaded that the biggest threat they should worry about was not something so abstract as black voting rights. It was what to them was the ultimate attack on their power as white men: Black men coming into their homes, and raping “their” women.

Black Men/White Women

In July, 1906, two months before the Massacre, the editor of a little rural newspaper in Georgia suggested that white violence had an important goal: Fighting back against black rapists, arsonists, and murderers who attacked whites because they hated them. This wasn’t what was happening. But that didn’t matter: Perception is reality.

White violence was the only answer, the editor wrote, and he repeated his argument in another editorial that was then reprinted in Hoke Smith’s Atlanta Journal. Between the summer of 1905 and the day of the Massacre, Atlanta’s white-owned newspapers wrote of a string of about twelve sexual assaults that black men were supposed to have suddenly committed against white women.

Max Barber responded with his own investigations. There was a black man, named Jim Walker, who had recently raped a white woman in Atlanta, he wrote. Walker was executed in December 1905. But, Barber argued, the remaining cases involved white women who were trying to distract family and friends from their personal issues, and while that argument sounds cringy today, there's evidence: White women tried to cover up forbidden affairs with black lovers, for example, men who treated them with care they didn't get from white husbands. One woman claimed a black man had attacked her to cover up her suicide attempt: That was according to white Northern journalist Ray Stannard Baker, who came to Georgia to investigate lynchings, and now investigated these rape allegations. Baker found that only two of the reported sexual assaults happened, including the one to which Jim Walker had confessed.

This was a very serious matter. The results for a black man who was accused of raping a white woman were catastrophic: On July 31, 1906, Frank Carmichael in rural Fulton County was lynched after a mob, in search of a black man who had allegedly raped a white girl, was led to his home by an untrained tracker dog. Although Carmichael did not fit the attacker’s description, he was shot dead.

The accusations continued. Two days before the white primary election on August 22, 1906, two sisters, Mabel and Ethel Lawrence, were alleged to have been raped.

James R. Grey (one of the Gang of Four and co-owner of the Atlanta Journal. with Hoke Smith), wrote in the Journal that white women should be armed with guns, and that every white man in Fulton County should be made a deputy sheriff, empowered to thwart rapists. He even envisioned these men doing their supposed duty in mobs. This suspicious timing persuaded Max Barber that the rape report was not a coincidence at all, that these accusations were concocted as part of Hoke Smith’s campaign. And once again, the stage was being set for the Atlanta Massacre.

The panic over rape continued, driven on by the elite and by newspapers. But the Journal and the Constitution were not the most shrilly racist papers in the city. Those were small papers that needed the sales.

In late August, 1906, just a few weeks before the Massacre, a small Atlanta newspaper ran a series of editorials on what it called “The Reign of Terror for Southern Women”, about the rape allegations, treating them as fact. Under the headline “The Way to Save Our Women”, the paper strongly hinted that the “reign of terror” should be ended by violence, if necessary. It asserted that whites were running out of patience for action, and that black men found guilty of rape should be castrated.

The Atlanta News and The Atlanta Georgian were both new publications, but they were run by men who got their start at the Atlanta Journal. They had learned how to sell papers with sensationalism. They went even further than the Journal, expressing anti-black views through their news and editorials, and completely ignored the Governor’s race to focus on sensationally racist pieces. Both these newspapers got full support from the Atlanta Commercial-Civic elite, including funding.

These two new newspapers became more and more focused on the harm that black men allegedly raping white women allegedly did to white men: Women were white men's property, and they had a duty to defend them. White women were even blamed for not making sure they weren’t seated well away from black men while riding on streetcars.

Anti-black violence was clearly around the corner. Atlanta’s Black Elite, panicking now, pointed to their own respectability, while they called on working-class black Atlantans to be “sober, industrious, and economical”, i.e. Guys, please stop drinking, go to work, and don’t splash around your cash. The desperate hope was to make black working-class people acceptable to the white elite, overnight. Meanwhile, the white press demanded more stuff the Black Elite couldn’t deliver, like the closing of every black-owned bar and dance hall in downtown Atlanta.

With Hoke Smith’s election as Governor, the papers argued, Atlanta’s authorities could work for a Progressive Atlanta. No booze, and a crackdown on bars and dance halls. Owners would have to show they were controlling the behavior of their black patrons.

Yet the press also claimed that Black people might already be beyond the authorities’ control. And this debate in Atlanta came during a national debate in the US on the place of black people. Now that black disenfranchisement was around the corner in a Hoke Smith administration, Black Atlantans were about to lose all power.

The Atlanta City Council chose this moment to ban Black people from buying guns. Under the circumstances, the council’s sudden enthusiasm for gun control was deeply disturbing to the Black community. John Hope, respectable college president, now turned gun runner: He got out-of-state friends to ship him weapons in coffins and laundry baskets.

In letters to the editors of the Atlanta News and Atlanta Georgian, working-class whites praised the small papers’ rabidly racist coverage. Some suggested changing the US Constitution to cover only the rights of white people. Others called for black Americans to be deported. And then there were letter writers who called for the genocide of Black Americans.

In the weeks leading up to the massacre, Atlanta’s white newspapers campaigned against the city’s black-owned entertainment businesses, bars, dance halls, and restaurants, mostly on Decatur Street,

The press attacked the customers of dance halls as “vagrants” and criminals, and claimed that black-owned places of entertainment were places where allegedly lazy people hung out instead of working. Clark Howell’s Atlanta Constitution demanded that there be a “relentless war” on these businesses, and that underemployed blacks (i.e. those enjoying recreation instead of working most of their waking hours as enslaved people had) be arrested and sent to join chain gangs (aka slavery under another name).

The Gang of Four, meanwhile, kept up the drumbeat for black disenfranchisement: Good times for all white people, and especially working men, that was their promise. Thing was, Howell, Smith, and Watson had been promising this for a long time. To make it happen was going to take what one white Georgian journalist called “an illegal revolution.”

And that, Dr. Mixon tells us, was the Atlanta Massacre.

After the Massacre

For the details, I suggest you get Dr. Mixon's book. Your public library can help you, or you can buy a copy. I will just sketch a few notes.

Scrambling in the aftermath, city authorities were concerned to make sure that black Atlantans did not stage a counter-revolution the very next day. Or any day. And that Atlanta not lose its reputation as a modern, progressive city.

That’s a very different set of goals in the aftermath of the Massacre than that of the Black Elite. Black leaders aimed to restore order to protect Black Atlantans, and especially the “respectable” Black elite to which they belonged. They were prepared to make all sorts of concessions for that goal, including accepting untrue and harmful white narratives about what was going on. But they did not yet realize—no decent, reasonable person would— exactly how much the white elite were now lined up against them.

Atlanta’s Commercial-Civic Elite had deliberately stirred up white violence through the city's newspapers. What the Massacre made crystal clear in 1906 was that Booker T. Washington’s attempt to “compromise” with white Atlantans in 1895 didn’t matter, assuming it ever had. Every black success was an insult to whites. Every black accomplishment risked sparking white violence. No matter what they did, black people were risking their lives in Atlanta.

Not even taking menial jobs, like messengers and barbers, working for powerful white men, would keep Black Atlantans safe, that was the lesson. They certainly weren’t safe owning their own businesses; Alonzo Herndon, the city’s most successful black businessman, did not take comfort from the fact that his shops survived the night of September 22. His windows were smashed, while the competing barber shop right across the street was a savage crime scene, where barbers were brutally murdered.

While the Commercial-Civic Elite wanted to restore order, these men also believed that the Massacre ensured their goals would be achieved: Most Black businesses were no longer welcome downtown. So Auburn Avenue, far from the center, would soon emerge as a ghetto for black business and entertainment, and while black Atlantans took much justified pride in the success stories that emerged from “Sweet Auburn”, this was not equality.

Max Barber, who wanted real equality, who hoped that a biracial elite could now rebuild Atlanta, was soon disillusioned in a way that’s familiar to anyone who has stepped out of their lane and raised a dissenting voice in the Deep South (do I sound like I’m familiar with this? Oh, hell, yes.) Barber wrote an article arguing that the rape allegations were concocted, that the newspapers were responsible, and that Hoke Smith’s campaign had done much to enrage the “riff-raff.” It was true, but truth wasn't a defense in Georgia. This attack on the Governor’s honor could not be tolerated.

James English, the former police commissioner whom the mob on September 22 told to “shut up”, and called a “nigger lover” was now chairing a commission on the Massacre. He sent for Max Barber. Alone together in his office, English told Barber that he needed to “straighten [himself] out . . . with white people at once.” He was told to leave Atlanta for good, or he would be arrested and put on the chain gang. Barber fled to Chicago, and he never came back.

Indeed, hundreds, maybe thousands, of Black people left Atlanta. Much of the rising black middle class was among them. Those who could not afford to leave, like Black street sweepers and garbage men, withheld their work, demanding the city government ensure their safety. Their reward was to be threatened with their jobs being given to white people.

Despite serious efforts to be part of the conversation, the Black Elite, including W.E.B. Du Bois, were shut out, and segregation was tightened. From now on, Du Bois kept a shotgun in his home. In his 1906 essay, "A Litany at Atlanta", Du Bois concluded that the Massacre had wiped out Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Compromise. It was dead.

Finally, Du Bois left Atlanta for New York in 1910 to take a leadership role in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which had grown out of the Niagara Movement, and which he had also founded. Rev. Henry Proctor moved to New York in 1919.

With the strongest leaders of their generation gone after 1906, and the vote taken away, Dr. Mixon notes, the Black Elite for decades would simply agree to whatever the Commercial-Civic Elite did. Things improved only with the start of a new voting rights campaign led by postal clerk John Wesley Dobbs in the 1940s. And only then did the white commercial-civic elite begin to work with the black elite.

The Atlanta Massacre, even more than the Wilmington Coup it had imitated (which was covered up as a “black riot”), became a blueprint for anti-black attacks in cities around the nation, not just the South. Springfield, Illinois, 1908. East St. Louis, Missouri, and Houston, Texas, 1917. Chicago, 1919. Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1921, and in various cities during WWII. Only in the 1960s, did “race riot” come to mean black people rioting in most Americans’ minds, as working-class black people protested the apparently never-ending racism that denied them good education and opportunity, and kept them in never-ending poverty.

And as for the Gang of Four who fought to unseat Clark Howell as Boss of Georgia? Who claimed they didn’t want a state run by “bosses”, but were happy to become bosses themselves? Frenemies Tom Watson and Hoke Smith battled each other for power until 1920, when Tom Watson won the election for US Senator for Georgia, defeating the incumbent who was . . . Hoke Smith. By then, junior Gang of Four member Thomas Hardwick was Governor of Georgia—but Hoke Smith remained boss, the power behind his throne.

Annette’s Aside: Buggin’s Turn

One thing I thought about: There’s a British expression that has no equivalent in American English. It describes a system in which people are put into power not because they’re the right person for the job, but because they’ve patiently waited, kissed up to their superiors, formed alliances, ruthlessly outmaneuvered their rivals, and now they’re at the head of the queue. Who shall we put in the job? I think it’s Buggin’s turn, don’t you? He’s waited patiently.

The Bugginses of this story are Hoke Smith, Tom Watson, and Thomas Hardwick. They made sure that no Black man, however clever, talented, educated, qualified, and full of integrity he might be, could threaten their claim to power.

Hoke Smith knocked Clark Howell off his perch, so it could be his turn, Buggin’s turn, and then that of other Bugginses, his allies and proteges, and their proteges. Georgia government was a very small club, and practically no Georgians were in it. Even the man who was by far Georgia’s most famous resident, the internationally-respected W.E.B. Du Bois, had been pushed out of any chance of power. But not before a Good Old Boy on an Atlanta Committee, having met Du Bois, had expressed amazement that such a black man existed.

So now came a new generation of white Georgia Good Old Boys to take power. Now they could achieve their goals: A progressive, modern Georgia in which white working-class people saw enough benefits to keep them quiet, and in which Black people had no meaningful role.

As Governor, Hoke Smith now turned to his Progressive agenda: More government oversight of railroads. A juvenile court system (he, unlike we today, at least understood that kids are not adults. Well, white kids, anyway). More funding for (white) public schools. Surprisingly, he ended the notorious convict lease system. I wondered about that, and he had many reasons that didn’t include a concern that this selling of prisoners’ labor disproportionately affected black men: I suspect that the unpopular competition prison labor gave to free white jobs had more to do with it.

Oh . . . and Hoke Smith took away the votes of Black voters, in 1908. In the New South that Henry Grady had planned, progress was to be for whites only.

Tom Watson ended up as US Senator for Georgia in 1920, but died just two years later.

Thomas Hardwick, who was Tom Watson’s protege, had previously been appointed US Senator for Georgia to replace another senator who died. He only lasted one term, but was soon elected Governor of Georgia, where he pushed progressive policies like prison reform and opposition to the revived Ku Klux Klan.

But the seeds of violent racism that had been sown in 1906 were now flowering: In 1923, Hardwick lost the governorship to a pro-KKK candidate, a Klansman himself, who invited Klan leaders to share power with him. Of that, white Georgia approved. More and more Black Georgians, meanwhile, continued to head for the exits, to Chicago and elsewhere.

As Dr. Gregory Mixon’s editors put it in their foreword to The Atlanta Riot, “The modern Atlanta that later boasted that it was “a city too busy to hate” was built on hate.”

Postscript

I often have a hard time persuading readers who love NBH to jump into my novels. Historical time travel about three middle schoolers? Nope. I get that. But it is a shame, because some of you, I know, started out as fans of my books. In hopes of persuading you to give them a go, I will tell you that, in the final book, one of my heroes ends up in Georgia, and Atlanta, in early 1906. He travels on streetcars. In ways that I made plausible, he meets John Hope, Alonzo Herndon, W.E.B. Du Bois, and even the family of restaurateur Mrs. Mattie Adams, who would be attacked, months later, in the Atlanta Massacre. And Brandon (for that is his name) experiences it all very personally, as a Black middle-class kid from Georgia. But don’t just take my word for it. Here’s what hard-to-please Kirkus Reviews had to say: