The New York of the US Northwest! Wait, what?

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD No, it's not Seattle. OK, yes, it is, but maybe only because a small city's dream fell flat

Nonnies (paying subscribers): Make the most of your summer! Non-Boring History Summer Museum Bingo is back!

(Ooh, and Nonnies? Don't skip the bit below about subscriber benefits! I have NEW perks for you as a big thank you!)

Note from Annette

A city consciously planned in the late 19th century as the US Pacific Northwest’s answer to New York? Surely that was San Francisco (which autocorrect just tried to change to San Defective, oh dear . . .)? Nope! Not San Francisco! Even if we can agree the Pacific Northwest goes that far south, which we can't.

Seattle, then? Probably, but not what I'm writing about today.

Sacramento? Oh, bless, my American home town, I love it, but . . . Don't be silly.

Okay, here’s the answer: Port Townsend!

Sorry, where?

Louder then: PORT TOWNSEND! In Washington State! Whose famous bright lights are admittedly not famous or even all that bright!

So obviously something went wrong with little Port Townsend’s dreams of glory. But why its ambitions sputtered and died is a lesson in what history demonstrates about urban planning, and historical chicken-counting in general: Unexpected Stuff Happens. This is why history is so much more useful, so much less theoretical, so much more colorful, so much fun, and soooo much less painful than economics (shudder).

That’s my big story for today. Oh, yes! Big, indeed! Unlike Port Townsend.

Things Worth Paying For

Before we go any further, I gotta say something to my free readers. I really do love that you read Non-Boring History. I get that you don't like paywalls. But— nitty gritty —my morale and the NBH Accounting Gnome require more money.

Oh, you think being a Substack bestseller means I'm pulling down millions? Um. No. Sob/Laugh. Honestly, and hard though this is for you to believe in crazy times, nor do I want to. I'm a missionary putting out the begging bowl. But to take the next (and rather exciting step) at NBH, I need more Nonnies. Like you.

So I keep thinking up new perks to persuade you that becoming a Nonnie is worth $5 or $6 a month to you! And that’s why you get these benefits when you join NBH as an annual, monthly, or Patron-level subscriber:

NEW! Random NBH Gifts! Imagine a little gift from me in your real-life mailbox! Maybe a postcard from my travels. Maybe a tiny bit of history. Maybe one of my novels. Nothing to gather dust. Just something small and unexpected to brighten your day. If you're a Nonnie (paying subscriber) , and you want to be included in the random but frequent drawings for these random gifts, it's a one-time registration: Email me at the usual address, or hit reply to this email, with GIFTS in the subject line, and your mailing address in the body.

Free admission to my live online history talks with Nonnies from around the US and the world.

Meet the Nonnie community and join in the discussion on posts. Or just lurk. Either is fine.

Indulge in NBH’s collection of more than 400 evergreen posts I’ve written since 2021 (they don’t expire anytime soon!) Find what interests you.

Meet me online and maybe even in person during my travels. You never know where I’ll pop up! And I love meeting Nonnies!

Get the full insight from posts written exclusively for paying subscribers.

Get a 20% discount on stylish NBH mugs and shirts at AnnetteLaing.com!

Get the warm fuzzies that being a Nonnie brings. You're helping me, Annette, cheerily spread the word about history at NBH.

And for Patron-level subscribers: A free personal online consultation to chat about museums and historic when you’re planning a trip in the US or to the UK.

More to come!

If this list persuades you to join, thank you. ❤️

I do understand that a paid subscription may not be financially possible for you. I do appreciate anyone who gives up just one unhealthy fancy coffee each month to pay NBH, but I definitely don't want anyone to skip a meal. So if that’s you, please don’t worry.

If you want to help anyway, here's how to be ruthless about it:

Print out one of my shorter(!) posts that you love, and give it to friends you think will enjoy it. Printed copies are harder to ignore than emails! They stare accusingly from bulletin boards, desks, coffee tables, and refrigerator doors.

When you have friends and family with you, like in the car, so long as you’re not driving, read aloud a short post, or an extract, preferably one of the funny bits. Then get them to Google Non-Boring History and subscribe. Don't let them out of the car until they do.

Mention Non-Boring History and Annette Laing every chance you get. Friends, neighbors, church members, family members, anyone. Until they break down and agree to sign up. Then get their phone, ask them for their email, and sign them up. With their permission, of course. Please don't mug strangers.

When I Close My Eyes, It Looks Like New York

Visiting Port Townsend in Washington State recently (glancing at Google Maps recommended), I learned that it’s not just a pretty tourist town, but a failed attempt to become New York City.

I almost missed out on the pleasure of that discovery because, well, this major info isn’t exactly posted on a big billboard on the edge of town.

But it should be!

WELCOME TO PORT TOWNSEND, THE NORTHWEST’S ANSWER TO NEW YORK CITY!

YEAH, WE AGREE THAT’S HILARIOUS.

But you don’t get these in Manhattan:

We’re nice!

Ample FREE Parking!

Elk, not rats, roaming our streets!

The Odd Grandeur of Port Townsend

“Wow, this is nice!” I said to Hoosen, my sidekick and long-suffering spouse as we entered downtown. I don’t know what I expected of Port Townsend. A few quaint fishing shacks? A gritty port with loads of crab pots and ropes lying about, and a faint whiff of fish? Tourist traps for my mindless entertainment? Ooh, I love some mindless entertainment! Historians are people, you know, and as my longtime readers know, some of us are positively trashy under that veneer of learning!

I wasn't surprised to see a bit of light touristy stuff, you know the sort of thing: Ice cream and fudge shop, junque antiques place, local artist galleries, charming cafes with a view of the water, that sort of thing. Not as trashy as I like, but very appealing all the same.

However, I was surprised that this beautiful downtown architecture on the main street (actually, it’s called Water Street) looks a teensy bit like the grand Victorian center of my Scottish home city, Dundee.

Port Townsend didn’t look to me like it had anything resembling Dundee’s gritty history, even though they’re both cities with big waterfronts.

Dundee’s Victorian entrepreneurs built hideous factories fouling the air with smoky chimneys, for the purpose of making beaucoup bucks for themselves. But they also spent some of their fortunes on grand architecture for the city, including a concert hall, a museum, and an orphanage. This isn’t something for which locals now like to give them much credit, mind, because, in Dundee’s hard-earned view, the money actually came from the efforts of poor people, toiling in said grim factories for so little pay, even the kids had to work to stay fed on bread and sugar.

Nobody could really imagine the end of Dundee factories until, well, in my early childhood, when they were disappearing fast after a long, slow decline: My dad looked around in the mid-1960s, went “uh oh”, quit his job, and went back to school, then to university. But local industry was on its knees by then, so I can't claim my dad was a brilliant prophet. People's denial about massive long-term change usually ends only as the curtain descends.

So Dundee factories moved to India, and the rich mostly drifted away, I suppose, to somewhere less depressing than Dundee, so they could pretend what happened there was nothing to do with them.

Hmm, but I wondered what happened to Port Townsend? It did not have a gritty Victorian industrial past, not from what I could see: The paper mill (est. 1927) is a relative newcomer. Port Townsend was a tourist town with a street of imposing Victorian buildings. Which was intriguing.

Local Heritage Can Be Deadly

At first, I didn’t even consider visiting Port Townsend’s local history museum. Local museums too often tend to be tedious places, stuffed with glass cases full of random stuff donated by easily-offended local worthies who get ultra-offended if their own donation isn’t on display. These museums are about heritage, about a nice idealized past for local consumption, not about history, which is clear-eyed, critical, and not particularly nice.

And such museums don't often tell visitors (or locals) enough about what makes a community different, much less how it's changed over time: “Ooh, look,” they say. “We have old-timey cooking pots and phones that you can see anywhere in any local museum in America! When are they from, you ask? Why, the olden days! And why are they special? Well, these are very special. They were given to the museum by the Burbles, a prominent local family, and they were used right here in Burblesville!”

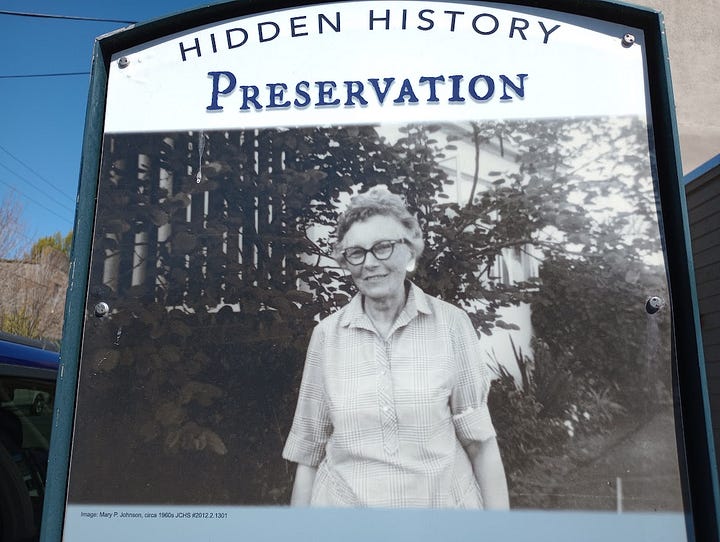

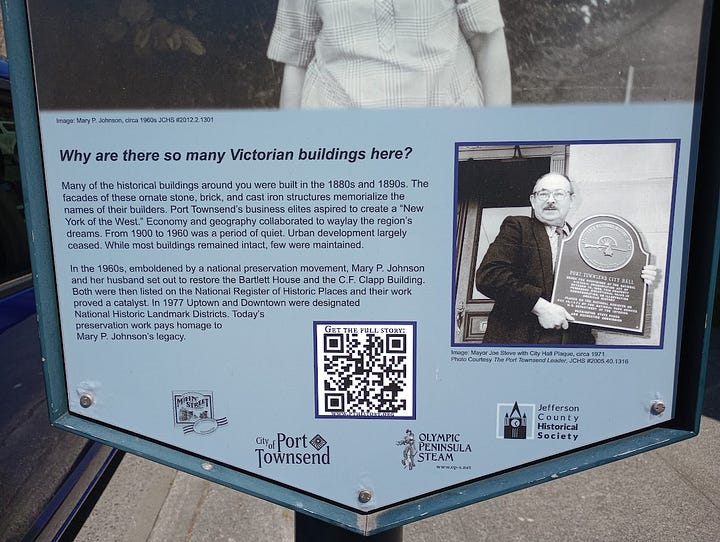

Port Townsend’s museum, as it happens, was not content to wait for us to come through its doors, and that was a good sign. It stepped into the street and came to us. The local historical society, which owns the museum, has put up “Hidden History” info panels around downtown. They’re certainly promising, although a bit uneven. One, which I've already mentioned in a previous post, was about several notable local fires: Every town has fires in its past, but what caught my attention was the mention of the deliberate arson of a S’Klallam Indian village.

I almost didn't bother with this next info panel in downtown Port Townsend, because a quick glance at the top told me the main theme: Let’s Celebrate Culture Lady!

There’s at least one Culture Lady in every community, and no, they aren’t all white. The most daunting Culture Ladies I met in the South were Black. What they have in common? They're all Culture Ladies! They do Cultural Things, and promote those Things. But then my eye traveled down to the text, because, c’mon, I can't be this snarky in good conscience without having read the text:

Here’s what it says:

Why are there so many Victorian buildings here? (Oh, unexpected! Good start!— A.)

Many of the historical buildings around you were built in the 1880s and 1890s. The facades of these ornate stone, brick, and cast iron structures memorialize the names of their builders. Port Townsend's business elites aspired to create a "New York of the West." Economy and geography collaborated to waylay the region's dreams. From 1900 to 1960 was a period of quiet. Urban development largely ceased. While most buildings remained intact, few were maintained.

Oooh! So this is how I learned about the “New York of the West” thing. But the remaining text is about the Culture Lady in the photo. Mary P. Johnson set about saving these grand buildings. Her mentioned but unnamed husband was Mr. Johnson, who I suspect was very quiet and got out the checkbook whenever he was ordered to.

Even if Mary P. Johnson is regarded as a local treasure by grateful Port Townsend citizens, and so she should be, with household altars burning candles in her name, she just isn’t thrilling for the rest of us. Hey, this panel serves as a statue to Mary P. Johnson done on the cheap, and it exhibits a really bad tendency in local history, of urging harmless tourists, as we try to take an interest in the local past, to celebrate locally famous rich people. Yay, Mary P. Johnson! Consider yourself celebrated! Okay, gotta go, ciao. It’s amazing if anyone stops to read this panel, even me.

But New York of the West? That’s what I’m here for!

Annette’s Aside: In all seriousness, I’m not just being flippant or unkind, although I am. Asking visitors to take time to go “ooh!” at local worthies isn't great public history. It doesn’t encourage the reading of other info panels. I should get credit for reading on, trying to figure out why I should give a rat’s patootie about Mary P. Johnson, much less telling you about her.

So Mary P. Johnson got into historic preservation in the 1960s, “emboldened by a national preservation movement”. She inspired Port Townsend’s local worthies to save old buildings.

As usual, despite the irritating tendency of small towns to reserve lavish praise for local worthies who are born and raised in a place, Mary P. Johnson, a woman who actually did something in town, who lobbied, pushed, and put her money where her mouth was, was a transplant from elsewhere. She moved to Port Townsend with her anonymous husband (Harry, I learned from scanning the QR code on the info panel, and reading the could,-be- better web page). She then set about pouring time, attention, and money into a couple of local buildings. Good for her, and well done, but this isn’t unusual in the period.

At least the panel reluctantly acknowledges (quietly) that Mary P. Johnson was “emboldened by a national preservation movement”. A lot of well-to-do people, especially women, tried to save old buildings during the 1950s and 1960s, in large part inspired by the wildly popular historical Disneyland that was the “recreated” (whitewashed) Colonial Williamsburg.

I'm certain there's a much more detailed and fascinating explanation of such preservation efforts in academic books, but our time today — yours and mine— ain't infinite. Sadly. Just know that Culture Ladies (and Gents) were all very keen on making a town look good, and persuading people that we can look at old buildings, and learn history through X-ray eyeball osmosis, which we can't.

But hey . . . Do you think you will ever think of Port Townsend, Washington, without thinking of Mary P. Johnson? See what I did?

But I ❤️ Old Buildings

Look, I’m all for the Mary P. Johnsons of this imperfect world saving old buildings. American towns, including the one I live in, are in danger of turning into Stalingrad, or at least of looking all the same as each other, as developers eagerly agree to build a few “affordable” overpriced flats so long as they’re allowed to throw up tons of exorbitantly overpriced flats and townhouses, and demolish genuinely affordable houses as they go, while ruining the appearance of American cities of all sizes. Bad enough the burbs all look the same: Now they’re coming for downtowns everywhere, and that’s frightening. Wasn’t this supposed to be something Communists would do to America? Yet here come the capitalists.

Yes, that’s an opinion. I’m a historian trained in the 1990s, when another period of museum building and historic preservation took place, and I’m also a Brit, from a nation where Victorian buildings are considered practically new-fangled.

Because of these things, I firmly believe that the sense of place that old buildings provide is important to human happiness. Knocking down old buildings to replace them with overpriced “luxury” apartments is only a solution to the affordable housing crisis in that these places are so badly-built, they will soon morph into cheap — nay, slum—housing a few years after the developers have fled the places they’ve ruined, carrying suitcases of cash.

Another reason I’ve always loved old buildings is because I grew up in a town that had very, very few of them by British standards. The town was developed by the British government to provide truly affordable housing for poor Londoners bombed out of the East End slums during WWII. It offered ordinary people, even those written off as riff-raff, well-built government-owned row houses. The laborers who built them were partly rewarded by getting priority to rent these houses for their own families. No wonder they were well built.

What’s happening now is not that, not well-built homes offered at genuinely low rents. Now, I watch as developers make unbelievable fortunes knocking down Victorian buildings (including those divided into affordable flats) to replace them with skyscrapers. In London, they have done more damage than Hitler did in the Blitz. Oh, and this is a bit of a horror film: Chances are, they’re in your town, too. Right now. Possibly looking greedily at your house and yard. Beware. Where’s Mary P. Johnson when we need her?

Which NYC Does Port Townsend Look Like?

When we look at Port Townsend’s skyline, at top, in my picture with the bird poop, we might think it's silly that the city’s bigwigs ever thought they could dream of competing with New York City.

But maybe we’re thinking about this wrong. We're comparing that skyline with Manhattan today, all skyscrapers and whatnot.

Here’s one part of the New York skyline as it was in 1876, around the time that Port Townsend was launching toward greatness, in the period when cities were booming after the US Civil War ended in 1865:

Compare the Victorian waterfront buildings of Port Townsend that survived to today, in my photo at the top of the post, with those of Manhattan in 1876, above! Port Townsend’s ambitions don’t seem so far-fetched now, do they?

Port Townsend’s heyday began in the go-go-go 1870s, when America emerged from its Civil War having built factories to mass produce things, like soldiers’ shoes and uniforms, and had learned how profitable this could be.

Port Townsend capitalized in being a port, a place of imports and exports, from and to China. By 1880, I learned from the short yet vague page behind the QR code on the Mary P. Johnson info panel, Port Townsend was already a big enough deal as an up and coming city to merit a stop on President Rutherford B. Hayes’s national tour, the theme of which was “Please Forget the Civil War Ever Happened, and Let’s Be Friends, So Long As You’re White.”

Port Townsend, as it happened, had quite a few Chinese residents, many of whom had originally come to America to build railroads. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was America’s first attempt to restrict immigration, and aimed squarely at people who weren't white. But immigration continued because, well, there were jobs to fill. Port Townsend’s local worthies kind of wished the Chinese would just go away, but they also needed them.

While many cities on the West Coast saw anti-Chinese riots in the 1880s, spurred by whites who didn't like competing with cheap immigrant labor, Port Townsend did not. The town and surrounding farms needed their work. So Port Townsend now became a port of entry for smuggling of the two Chinese products Americans wanted most: Illegal immigrant workers to do hard work cheap, and opium on which to get stoned. Whenever customs officers approached a smuggling boat, the Chinese people were chucked over the side, to literally sink or swim. The Chinese community was never truly welcomed in the 19th and early 20th centurie. When fire came to Port Townsend in the 1890s, the local fire company concentrated on saving white homes and businesses, and allowed Chinese -owned and occupied buildings to burn. The Chinese community gradually drifted away.

Still, though. New York of the West! How?

The Mysterious Death of the City

But why did Port Townsend’s boosters’ (rich cheerleaders’) dreams die? The info panel is not a lot of help, and neither is the web page to which its QR code led, which is written in a breezy tone that makes NBH look like heavyweight literature in comparison.

The info panel says only “Economy and geography collaborated to waylay the region's dreams. From 1900 to 1960 was a period of quiet.” Which unfortunately implies that Fort Townsend’s dreams ended because things were a bit slow after the turn of the 20th century. That doesn’t tell us much, does it?

Look, I understand why, at this point, you might be thinking, “Yeah, ok, that’ll do. Never heard of this place, and that’s enough for me.”

Fair enough, but I wanted to know more, and I didn’t have time or books to dig deep. There’s an academic book on the rise of Port Townsend,(Elaine Naylor, Frontier Boosters. Port Townsend and the Culture of Development in the American West, 1850-1895) and a review of it I have read makes the book sound fascinating, but the review doesn’t tell me if the book explains why the town’s New York dreams collapsed.

So I did what I normally do for Annette on the Road posts like this: I looked it up, best I could, on my phone.

That’s when I realized that Port Townsend’s growth came to a screeching halt for many reasons: No railroad came. Seattle was better placed to benefit from growth of all kinds. But there are also clues about timing: Things fell apart in the 1890s, and that matters.

Unregulated capitalism (or, as it was called when I was at school in Tudor England, laissez-faire capitalism, which means, in English,“You can do what you like) met its match in the 1890s. It met reality.

Hey, my expertise is focused on 18th century cultural history, but as I understand it: Unrestrained by government, capitalism inevitably has a boom-and-bust cycle. Or, put more simply, when richies get to charge around doing what they like to make more and more bucks without paying attention to whether what they’re doing is wise, then, eventually, everyone else has to pay the piper— it’s not usually the richies. One reason few saw the 1893 crash coming was that economic growth like this was new to America after the Civil War: Big cities! Factories! Trade! Massive! Money, money, money! How could this economy ever go anywhere but up?

They found out with the Panic of 1893. That doesn’t sound like a big problem, does it? You panic, you get over it. But banks around the world collapsed, along with real estate projects and companies. More than 125 railroad companies folded. There was no Federal Reserve Bank in the US, so hundreds of banks collapsed, ending funding for so many plans. Oh, and the Fed is a product of the 1930s Great Depression, and it's why we haven't had a Great Depression since.

What happened after the Panic of 1893 should really be called America’s Secret First Great Depression. By 1894, more than 40% workers in Michigan were out of work, 35% in New York. Think things are bad now? Think again. In 1893, there was no federal unemployment or welfare, just local government relief and charity that couldn’t cope with a crisis on this scale. For four years, Americans starved, families fell apart, workers went on strikes and protest marches, and finally, William McKinley was elected president because he promised to do something to help. He was shot dead by an unemployed man who wasn’t convinced.

In that context, the failure of Port Townsend to become the Northwest’s answer to NYC is what we might now call a First World Problem. But I still cared!

To see if I could find out more about Port Townsend’s ruined big city dreams, I broke down and opted to go to The Jefferson County Historical Society’s museum, and fork over admission for Hoosen and me. He’s such a good sport, is Hoosen, so I do cover his admission, plus I’m married to him, so it would be a bit rotten of me to leave him outside on a park bench.

The museum itself is the best bit of Victorian architecture in town. It's the sort of grand civic architecture that Victorian richies loved to build, not least because great civic architecture yelled “This is the place to be!: and brought more people and investment to town, and to business-owners’ pockets. This once was the town’s court, jail, and fire station, until the newer Victorian courthouse (even bigger!) was built. Lots of original features inside, including the cells:

Surely, the same museum that had the good idea to have info panels on the streets would be better than most local museums? Alas, it was the usual object-centered local museum, heavy on photos of local worthies and artifacts we might find anywhere. Most of us walk out of such places no wiser than when we walked in, only to write a five-star Google review about how it included “lots of information” so we don't feel stupid.

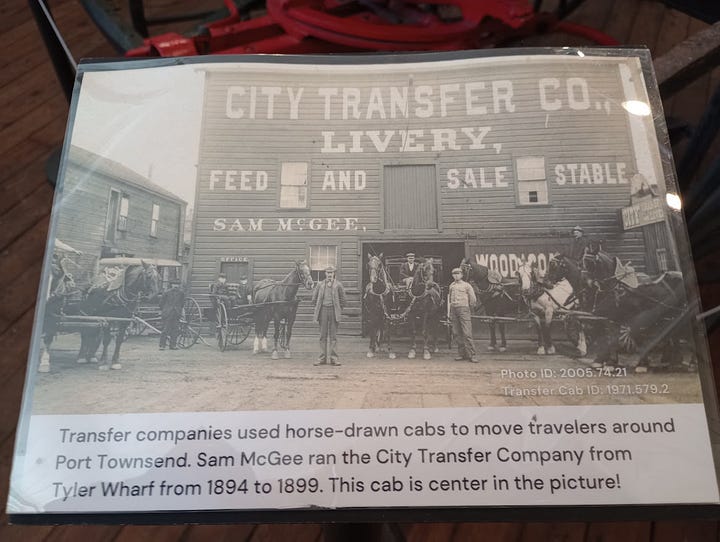

This photo of a livery (think car rental and cabs), plus one of its actual horse-drawn cabs on display, could, I guess, serve as evidence of Port Townsend’s ruined ambition for city glory:

But that’s a bit of a stretch, really. And the rest of the museum was light on story, too: Ok, an exhibit on the S’Klallam Tribe (with hastily added new interpretive material from, um, the S’Klallam people themselves), was encouraging, as was the exhibit on a new graphic novel about the local Chinese community. But, without going on and on about it, this was not a great museum.

Good news, though: The enthusiastic and informative young woman who greeted us at the desk finally revealed under close questioning that yes, the museum is to be redone, and fundraising is underway. She’s very excited. NO, this is, I promise, not something “woke” but something great, something necessary, because otherwise, this museum is really, really dull.

So I didn’t learn more about the New York thing. But the city boosters’ legacy? A little town with a very fancy downtown. Adorable elk do indeed roam in Port Townsend. I don’t think it’s a great idea to pet them, though, any more than it’s a good idea to pet a resident New York City rat.

I think Port Townsend is great as it is in 2024, albeit a bit pricy. I wouldn’t object to living there, myself. But I don’t want to give support to the greedy developers who promise “affordable'“ housing, and yet deliver oddly unaffordable versions of Victorian tenement flats.

Dr. Annette Laing, author of Non-Boring History, is a British renegade history professor in the US, who quit her tenured job at an undistinguished university in the Deep South in 2008. Ever since, she has devoted her life to connecting the public with history—the real public, not blokes in bow-ties who went to Yale. At NBH, Annette writes a wide variety of posts on American, British, and transatlantic history, showing along the way how academic history and museums work, and how knowing more about them is not only entertaining, but life-changing. Thank you for your support.