Democracy in Deep Doo-Doo 💩 (2)

ANNETTE TELLS TALES Kansas Goes From Bad to Worse to John Brown's Bodies, Part 2

Notes from Annette

New to Non-Boring History? This is an Annette Tells Tales post, in which I chat about stories from a work of academic history in plain English, while giving full credit to the historian, and doing as little violence as possible to the author’s argument.

The latest from NBH for Nonnies (paid subscribers) is this “interview” with the Bank of England about its shocking history with slavery:

Oh, and if you’re reading this post in your email, please do yourself a favor. and always click on the headline to be taken to the website. I fix things even after I publish: I’m my own researcher, writer, editor, chief cook, and bottlewasher. This is a newsletter, very much a personal project in partnership with Nonnies, paying subscribers.

FLUB ALERT: Before we go any further, I must point out that in Part 1, thinking of my non-US readers, I gave a quick explanation of the Louisiana Purchase, and mentioned that Alabama and Mississippi were part of it. Brain fart. They weren't. I've corrected this on the online version of the post, and thanks to the readers who pointed it out. Nah, this “gotcha” doesn't mean I have to give back my PhD in early American history! 😂 Not how these things work, and obvs I need a whole series dedicated to why that is . . . Rabbit hole alert . . .

Today, I'm wrapping up Democracy in Deep Doo-Doo, my absurdly huuuuuuge riff on Dr. Nicole Etcheson's book Bleeding Kansas.

Didn’t read Part 1? Here it is, and it’s a free post:

HUGE thanks to the Nonnies, my paid subscribers, for your supporting my work, even (or perhaps especially) when it's HUUUUGE.

The Story So Far

So, in Part 1 of Democracy in Deep Doo-Doo, we saw how there was a race between white Northerners and white Southerners to settle Kansas in the mid-1850s, and that the main issue in that race was slavery. This was really a contest over the meaning of freedom. I don't mean over the freedom of black people not to be enslaved, like we might reasonably assume, given that, yes, slavery was the issue leading the entire US toward civil war. But that doesn't mean white people settling Kansas, even the majority who opposed slavery ,were concerned for enslaved black people in the 1850s. Most of them were mostly worried about slavery making slaves of them.

How's that then, you might ask? Indeedy! This contest in Kansas was about two clashing meanings of American freedom for white people. Northern whites saw voting rights and representative government as their guarantee of freedom, of not becoming unfree (or, as they put it, enslaved) themselves. Being free included being able to earn a decent income, and not having to compete with slave labor. Freedom also meant the opportunity to become independent from bosses by owning their own land, rather than being shut out of land ownership by slaveowners who could afford big bucks for real estate.

Southern whites, however, thought more in terms of individual freedom, and especially their rights to own people and get rich from their work. Please note: The right to be a slaveowner remained theoretical for the vast majority of white Southerners. They tended to be dirt poor by Northern standards, because they had to compete with slavery. They were persuaded, however, that they too could be rich, if they worked hard to buy an enslaved person. For practically all of them, that didn't happen. The right to enslaved “property” was so essential to white Southerners’ freedom, they believed, that not even a white majority vote in an election should be allowed to overrule it. Anyway, most elections (outside New England) were pretty informal, indeed, often corrupt affairs, so no big deal if they interfered in one.

That's why many people who lived in the slave state of Missouri saw no moral dilemma in popping into the Territory (emerging state) of Kansas to vote in elections that would ultimately decide whether Kansas would be free or slave. Kansas was in a fluid situation: It was just being settled. Why, the Missourians reasoned, should a few randos (there for political reasons, they assumed) get to decide something so important to so many white citizens?

Hey, did you see what I just did? I did my best, based on my reading of Nicole Etcheson’s work, to explain how proslavery whites in the South thought in 1855. Look, anyone who thinks that Dr. Etcheson or I favor the white South in 1855 needs their head looking at! But historians don’t just try to understand only the dead people we like. We have to try to grasp everyone’s perspective, to get into their heads. That’s because the pursuit of historical truth requires historical empathy—not just empathy for those we feel close to, but even more crucially, for people we don’t sympathize with at all. Even though I have spent many disturbing hours reading slaveowners’ letters and diaries, I always feel most for my colleagues who study Nazi Germany. Which genuine historian wants to be in Nazi heads? None of them, but duty calls. (Fan girl shout-out to the amazing and (I trust) lovely historian Sir Richard Evans). Nobody can understand why Germans became Nazis without getting into their heads. Likewise, nobody can understand proslavery people in Kansas without doing the same.

BTW, half the point of NBH isn’t the historical content. It’s explaining what history is. I give no toss how easy this looks. It’s bloody hard work. If you’re not a Nonnie, please join us. You’re funding the work, not someone’s luxury lifestyle.

The two sides in Kansas—proslavery and free-soil/free-state, were both complicated. We're gonna stress that, because this is why you read NBH, not just a simplistic rehash of a textbook. The details are the important bits. And here is also my latest reminder to us all (me included) to keep an eye on our own confirmation bias, not to be quick to assume we're reading the present—and what we want to see—into the past. I'll come back to this shortly.

What the Missourians didn’t factor in was that only a minority of Kansas settlers were New Englanders, people from the most anti-slavery area of the US. Nor did the Missourians realize that only a minority of New England settlers in Kansas were abolitionists who believed in ending slavery throughout the US.

Even in Lawrence, the most abolitionist settlement in all of Kansas, the vast majority of New Englanders who had moved here did so first and foremost to make money, no matter how many Black Lives Matter signs they proudly put up in their front yards.

Yeah, I'm joking about the signs, but otherwise that's what Dr. Etcheson is arguing. Note the story I told in Part 1 of how, when three white Missourian men came to Lawrence to kidnap a black woman, nobody but her lifted a finger to stop them. These were not white people who put a priority on tackling racism.

Many Kansas settlers were not from New England anyway. Many were from the US Midwest (part of the free North), and were free-soilers (opposed to slavery where they lived), at least as far as Kansas and the Midwest were concerned. They didn't give a toss about slavery in the South, or black people in general. The Midwesterners in Kansas were led by Jim Lane, who reflected their views: pro- free white labor, and vocally racist.

AND . . . a small but interesting minority of Kansas settlers were poor white Missourians who had no objections to slavery, so long as they didn't have to live with it: They, too, were free-soilers who came for the cheap land and the lack of competition from unpaid workers. Most Missourians who settled in Kansas hoped to own lots of slaves, and get rich: They were not already rich, because most brought no enslaved people. Those who did only brought one or two, some of them children, which means these slaveowners were not rolling in dough, although they hoped to. You could not get un-poor in the South without somehow earning money from slavery.

Fact is, most white Southerners could not see the point of moving to Kansas. Cheap land was still available in states where the right to own slaves was enshrined in law, including in next-door Missouri. From their perspective (which—again— we don't have to like, but we do have to understand if we're to understand what's going on), why would they move all the way to the Kansas Territory? Plus, if a majority of settlers now voted to make Kansas a free state, they would lose their human “property” and see their land value collapse. Why go?

That’s why the only white Southerners who were willing to gamble on moving to Kansas were those who were not rich, but desperately hoped to be. Efforts to persuade other white Southerners to move to Kansas on principle, to defend Southern slavery and the national power of slave states, were not successful.

And if people in western Missouri were worried that Kansas could become a free state, and provide a tempting refuge to enslaved people? They realized they didn't have to settle in Kansas in order to vote in it. They could just take a day trip!

Sure, their voting was fraudulent, and their intimidation of actual settlers who tried to vote for a free Kansas was technically illegal. But the shambolic state of the US voting system assured Missourians they would get away with it—and they could even pay some poor man to take the risk instead, the so-called “Border Ruffians”. Plus, just like the free-soilers, proslavery Missourians saw themselves as the heirs to the values of the American Revolution, and that was worth breaking rules for!

You may be wondering where John Brown is in this story of Kansas. I promised you John Brown, and gosh darn it, I'm gonna deliver him, dead or alive, okay, dead. In fact, that commitment is part of why this riff on Bleeding Kansas is so bleedin’ long: Dr. Etcheson’s context for John Brown comes first, and it’s beautifully expressed in details I was reluctant to omit, lest I not represent her work properly.

But we’re heating up high-quality historical cuisine here, not collecting drive-through junk for the brain. To quote prominent Kansas Oz resident Miss Wicked Witch of the West, “All in good time, my pretty. All in good time.”

Long though this post is by NBH standards, I’m only offering you an on-ramp in my familiar voice to Nicole Etcheson’s book. My goal at NBH is to platform and promote my fellow historians’ work. All the more reason, if you’re captivated by this story, to go grab yourself a copy!

Thinking Historically

I know a lot of readers made your minds up in Part 1 that my interpretation of Etcheson’s book confirmed what you have already decided to think about the current state and future of the US. I can see why. But that is never my goal (not a fortune-teller, not a guru) and that's why I ask you to keep an open mind as much as possible.

Open mind, you may be asking with raised eyebrows? Yes. Historians, as people, are not amoral. We agree that piles of the bodies of innocent people are bad, so is slavery, and so is Nazism. But we are, if we’re doing this right, cautious in passing judgment on the past as historians, and most of us are cautious: That is what historians are trained to be. Look, like anyone else, we jump to conclusions, but we're taught to always remind ourselves that that it’s something we all do, and then we are obliged to reconsider, to examine evidence, to keep thinking and keep reading, to remain open to the possibility that we're wrong.

After several years of Americans calling other Americans Nazis because they disagree with them on issues that have nothing to do with, erm, actual Nazis and actual Nazism, I ask you to keep an open mind (hard though that is) on past Americans’ beliefs and motivations, which were often fluid. Otherwise, we can't explain historical change: How did the US embark on the Civil War? How did freeing enslaved people become the Civil War’s goal (and during the War!), when, in early Kansas, just a few years earlier, we see that abolitionists were a tiny minority among white free-soilers?

If we're going to understand anything about the past, then rather than simply list goodies and baddies and assume that’s enough, we have to be alert to nuance, to gray areas, to stuff that surprises, and be prepared to revise our assumptions. If any historian is offering up historical facts and interpretations without telling you that, then that really bothers me, as it should. Democracy depends on an educated citizenry, and “educated” does not mean being told what to think, but being taught how to think.

Hand on heart: I had both parts of this post drafted before Part 1 appeared, and thus before your comments. In reading Atcheson’s book, I, too, was struck by parallels between 1855 and now. But what got my attention was difference. I was struck by how these people in Kansas associated with each other, how they affected each other, and how almost none of them were as easily categorized as heroic or as villainous as we might hope.

Look, I could make this all much simpler and shorter, and thus make myself more popular and richer, but, alas, that's not my destined role in life, it seems. I would try to persuade you that fame ‘n fortune are not my goals, either, but I find that Americans tend not to believe me, unless they know me. A pity. I wish they'd met the British WWII ladies who got their claws into Annette at an impressionable age.

But without further ado . . . Back to Kansas.

The Governor’s Dilemma

The chaotic and corrupt March 30, 1855 election for the Kansas territorial legislature didn’t just shock free-soil settlers in Kansas. It even shocked a few proslavery Southerners, who saw the Missourians’ invasion as lawless mob rule, no matter how important the cause (i.e. defending slavery).

The complaints about the March 30, 1855 elections were piled high on Kansas Territory Governor Reeder’s desk. He got reports on the intimidation of voters and judges, and on fraudulent voting, mostly by proslavery Missourians, most of whom still lived in Missouri. They had come on day trips to ensure that proslavery men were elected by any means necessary.

Gov. Reeder threw out results in six districts’ elections (almost certainly far fewer than had actually been corrupted), and he ordered special elections in these six. All six special elections went off peacefully in May, 1855, and free-soil candidates won.

But Reeder had done too little, too late: The new Kansas territorial legislature was overwhelmingly proslavery. Proslavery men nonetheless called out Reeder as a tyrant for intervening at all against what they saw as the people’s will. By “people” , of course, they meant blokes who had popped over the border from Missouri to vote, and to terrorize actual Kansas settlers from voting. They considered these day trippers (many of them paid to go vote) as true patriots, as revolutionaries defending American freedoms (slavery) from idiots and corrupt abolitionist New Englanders who (they thought, wrongly) were themselves in Kansas only to vote.

After all, proslavery Missourians reasoned, rich abolitionist New Englanders had paid for migrants to come to Kansas specifically to vote. Except, of course, we already know most people came primarily for the same reason as everyone else who moved west in America: Economic opportunity.

That's the problem with thinking for oneself without knowledge of facts, and lots of them: The New England Emigrant Aid Society (NEEAC) did indeed offer support to some New England migrants, but it wasn't much, and certainly not enough to justify people moving on principle.

Again: Most New Englanders who came to Kansas weren't keen abolitionists. They came, like everyone else, to make money.

Oh, and most free-soilers who moved to Kansas from the Midwest had never even heard of NEEAC.

The same proslavery men were now claiming that Gov. Reeder was violating their rights. They were the victims here, they cried. I don’t know about Gov. Reeder, but I feel like a stiff drink just reading all this stuff. Gov. Reeder obviously wasn’t feeling too confident in dealing with it, because he responded by heading in person to the City of Oz Washington, DC to appeal to the Wizard President for backup, not an easy journey in 1855. There, he asked President Franklin Pierce for authority—and troops—to hold a new election for the legislature.

But President Pierce was a northern Democrat, and we know what that means from the hopeless situation of Senator Stephen Douglas, the Northern leader of an increasingly Southern Democratic Party. It means President Pierce was a bit of a humbug, a fraud. Instead of thinking of what was best for Kansas and the nation, he was worried about ticking off the white Southerners on whose support he depended. When he met Reeder, they mostly chatted about how to manage Reeder’s resignation as governor of Kansas, which didn't actually happen . . . Yet. He sent Reeder went back to Kansas, to try to deal with a witch legislature that didn’t represent the people of Kansas.

Free-soil Kansans, unlike Reeder, were not content just to go along with a corrupted election. In June, 1855, they held a convention in Lawrence, to discuss how to respond to what they considered an illegitimate legislature. The convention called on the free-soilers elected in the May special elections to resign in protest.

Proslavery legislators, meanwhile, doubled down on their dodgy victory in the March 30 election. They rejected the legitimacy of the free-soil winners of the May special elections. They denied Gov. Reeder’s right to overturn any election results. All the free soil representatives now resigned in protest, which I can't see the proslavery legislators minding much, but hey.

The proslavery Kansas territorial legislature now went even more rogue. They decided not to join the Democratic Party, even though the Democrats were the party of white Southerners and a declining number of white Northerners, among whom was the increasingly nervous Northern Democratic President of the United States, Franklin Pierce. Instead, they formed their own Proslavery Party.

To make things absolutely clear, the Kansas legislators explained in an official resolution:

“That it is the duty of the Pro-Slavery Party, the Union-loving men of Kansas Territory, to know but one issue, Slavery; and that any party making or attempting to make any other, is, and should be held, as an ally of abolitionism and disunionism.”

In other words . . . According to the dodgy proslavery legislators, if you were a Kansan active in politics, and you were not 100% focused on the single issue of promoting slavery, you were a damned abolitionist-lover AND an unAmerican who supported the breakup of the US, so you should pretty much be cancelled.

Yet Another Bloody Aside (sorry)

Now is the time to remind you I chose Dr. Nicole Etcheson’s Bleeding Kansas because (a) I promised to write more for you about John Brown and (b) The book looked interesting. Turned out, it was so interesting, that I found myself going down the rabbit hole early, to understand the context for John Brown,

The book was published in 2004, not 2024, so Etcheson didn't have one eye on the politics of right now.

Everyone has a different take on what they read. I now know that many of my readers are understandably trying to use this two-parter as a template for understanding what’s happening in current US politics and political life, in a confusing and concerning time. But I want to gently push you to be calm and cautious, because my goal isn't to tell you want to think, but to help you think as historians are taught to do, habits of mind that I happen to believe are incredibly useful for everyone.

Historians aren't entirely comfortable (or shouldn't be) when the public tries to spot history repeating itself. As historian Dr. Jennifer Goloboy said in our recent chat at NBH, we're trained to see differences in the past, and things are always different. We are trained to see change over time, and not settle for similarities. We are trained to keep minds open to evidence, and especially when the evidence challenges what we thought we knew.

This way of thinking isn't easy (or even possible) to master, and I know because I've been trying and failing all my life: I'm 100% certain that today's headlines influence how I read history, despite my best efforts. We're all. products of our lives and times. But trying to think like historians is more fun, far more useful, and, I think, more important than playing a matching game between past and present, as I hope to show.

And this is also why your paid subscriptions matter. What a dilemma I have. My impulse to keep prodding everyone (including myself) to approach knowledge with humility, to keep jumping around, trying different perspectives, is why I'll never be popular or rich, as I said to Hoosen recently, unlike historians and journos who tell you what you want to hear. “But if you did,” Hoosen said, “You wouldn't be Annette Laing.”

There was a moment’s pause while I fleetingly considered how it would feel to not be Annette Laing, but own a Maserati. And then I felt my inner Calvinist kick in, and felt a breeze of frosty disapproval from the British WWII ladies who influenced me in my youth, as they reached out from the grave to smack me upside the head.

Ah, well. I'm fond of my old Toyota, and lucky to have it. And as my old history teacher said, “All trouble in the past is caused by money…” You know the rest. Well, the Nonnies do. After all that, I hate asking, and I won’t be buying a posh car, because the Toyota is staying. But it always needs gas to get to museums.

Freedom?

The proslavery Kansas legislature, elected March 30, 1855, passed laws relating to slavery, which pretty much made clear that slavery was coming to Kansas. They made clear that they intended to gag critics of slavery itself, with draconian punishments promised for abolitionists who didn't mind their own business and keep their mouths shut. Some important highlights:

Anyone who wrote or distributed antislavery materials would get two years imprisonment at hard labor (like breaking rocks).

Anyone who “stole” slaves (helped enslaved people escape) could be punished by imprisonment with hard labor, or by death.

In trials of people accused of any of the above, critics of slavery were not allowed on the jury.

Paper ballots were no longer allowed. In an old practice largely abandoned elsewhere in America, but still common much of the South, Kansas voters would now announce their votes aloud at the polling place, nice and loud, so everyone at the polls could hear them, because, according to proslavery leader Benjamin Stringfellow, paper ballots were for cowards. 😬

Spoken votes, of course, were meant to silence not only the handful of abolitionists in Kansas, but all free-soil voters. Stringfellow saw no shame in this. He told an Alabama newspaper that Kansas now had the best state laws in the nation for protecting slavery, and that abolitionists had been “silenced”. You see his priorities: Slavery as an American value trumped free speech hands down. At the same time, Stringfellow, like most proslavery people, either didn't understand, or didn't think he needed to care, that most free-soilers weren't abolitionists.

But here's where things get more complicated, and even more interesting. A Kansas postmaster refused to deliver the antislavery newspaper Herald of Freedom, the official publication of the NEEAC, which was published in Lawrence. He returned it to editor George Brown with a letter telling him to keep “your rotten and corrupt effusions from tainting the pure air of this portion of the Territory”. In other words, the postmaster was telling Brown to shove his antislavery newspaper where the sun don’t shine.

But as Dr. Etcheson notes, Brown was not prosecuted and imprisoned, which he certainly should have been under the draconian new Kansas anti-free speech laws. Maybe the postmaster didn't rat out Brown. Or the authorities decided not to prosecute. Either way, there was reluctance to go after a neighbor they likely knew. Dr. Etcheson also points out that there is evidence that some members of the proslavery Kansas legislature were disturbed by the attack on free speech. In other words, the divide between people was not total.

I want to stress this. There weren't a lot of people in Kansas as a whole, and certainly very few in each settlement. I don't think any settlement was entirely made up of proslavery or free-soil settlers. None was exclusively abolitionist, and actual abolitionists were few. People in Kansas were getting to know each other as neighbors. Again: It's harder for most people to be draconian to individual people they actually know in person.

Meanwhile, free-soil forces were just starting to get their act together to push back against the legislature, in what was a fluid situation. One man warned Sen. David Atchison, the proslavery Missouri politician with a keen interest in Kansas, that free-soil settlers were NOT enthusiastic abolitionists, but they would be soon if the legislature didn't knock off its oppressive measures.

Free-soilers, including abolitionists, were indeed becoming more outraged by how white people in Kansas were losing American freedoms (and they actually were, specifically free speech and voting rights). In Lawrence, where the city planned Fourth of July celebrations to be a protest against being “subjects of Missouri”, a woman named Sara Robinson wrote “We in Kansas already feel the iron heel of the oppressor, making us truly white slaves.” Exaggerated? Of course. Slavery in 1855 involved a total loss of freedom that Sara Robinson would not have been able to wrap her head around. But slaves was the word she used, and she wasn't alone among Kansas whites in using it, regardless of their politics. As one of my old professors liked to say, “Perception is reality.” No, Sara Robinson was not enslaved. But she thought she was, and that shaped her beliefs, her assumptions, and her actions.

Sara Robinson was the wife of Dr. Charles Robinson, the man who gave the speech at Lawrence’s July 4 picnic, quoted near the start of Part 1, in which he riled up the crowd of free-soil New Englanders. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, he said then, “is made to mean popular sovereignty for them, serfdom for us.” So much for self-government in the United States of America, he implied. The potential for white Northerners to be deprived of American freedoms, not the actual enslavement of black people, was their biggest issue in Kansas. Look at the laws passed by the legislators to restrict their free speech. But consider also that even these laws were not carried out, and what that might have meant.

The proslavery Kansas legislature, meanwhile, worried about Governor Reeder. Would he veto their laws?

But Gov. Reeder had his own problems: Although grifting was normal for mid-19th century politicians, the Pierce administration was concerned that Reeder’s land investments in Kansas would open him to attack as a corrupt politician.

Wait, Laing . . . What land investments?

So Gov. Reeder insisted the legislature meet in Pawnee, Kansas, on land that he had bought with a view to building the state capital on it. It was land he had bought and owned personally.

So he was a grifter? But I already wrote his name in my good guy column, and in ink . . .

Ah, facts go in ink in history (although leave room for more yet to be found, and know that sometimes we get things wrong, especially in the details, and sometimes we find facts that we didn’t know were facts!) Interpretations should always be written in pencil.

So, as I was saying . . . Governor Reeder owned the land on which he wanted to create the state capital. He had even started construction on a capitol building, but it was still a windowless, doorless shell. Legislators, who were having to camp outside, were not pleased. They voted to move their meeting place to Shawnee Mission. Reeder vetoed their proposal. They overrode his veto, and moved anyway.

Reeder did not give up on Pawnee. He had too much personal money at stake. He vetoed every bit of legislation the Kansas legislature now passed, on the grounds that the legislators weren’t in Pawnee, the non-existent capital, and therefore the legislature was not legitimate. So there.

At the same time, Gov. Reeder hinted darkly to his wife that the legislators might have him killed. They didn't, but Benjamin Stringfellow did challenge the governor to a duel. Reeder declined, so Stringfellow jumped him, and the men struggled on the floor, guns drawn. Both survived.

Wow, Laing, I thought things were uniquely messed up now! Lol!

They are uniquely messed up now (however and whyever you think that is). They were uniquely messed up then. Every bit of history is unique, every context different, every era. That’s why I cringe every time someone concludes that a historical phenomenon was “just like now”, and tries to make a template for understanding the present from selective reading plus confirmation bias. We all do it, mind, including me, but it’s best to do as historians: Stop, count to ten, think, and read more.

I’ll say it again: Every mess is its own thing. The past isn’t as tidy, isn’t as simple, isn’t as bloody nicey-nicely predictable as it appeared in the textbook you probably had at school, unless, maybe, you were very expensively educated at an elite boarding school, or got lucky (as I did in England)

What was that textbook called? Triumph of the Republic, something like that? Conservative friends, I am NOT advocating the opposite (America Sucks!) There’s another way altogether, it’s what the vast majority of academic historians do, and, in the end, we upset everyone, because people want neat and tidy and authoritative, when we would, I gently suggest, all be better off if we embraced complication in a spirit of humility, at least considering that we might be wrong.

Now the legislature demanded Gov. Reeder’s firing, and President Pierce fired him, but not for bias toward the cause of free-soilers, the charge his enemies would have preferred. He was sacked for an ethics violation, i.e. arranging to build the Kansas state capital (and capitol) on his own land.

Reeder’s response? Now he wasn’t Governor, he took a side and gave its partisans what they wanted: He began making speeches supporting free-soilers. And he was widely expected to have a warm welcome in the East, when he returned from Kansas. He was already being considered as a candidate for Governor of Pennsylvania, because disguising grift and ineptitude in attitude and fancy words and saying popular things worked for him. Imagine that.

Meanwhile, Kansas free-soilers were no happier that the proslavery legislators were: They were portraying popular sovereignty as a joke, since majority rule was clearly not happening.

It was in this climate of low confidence in the Kansas Territorial Governor’s office that Gov. Reeder was replaced by Wilson Shannon of Ohio, who was a bit useless, and described by one unimpressed Kansas settler as “an old fogey”.

New Gov. Shannon had already made up his mind to accept the proslavery Kansas legislature as legitimate. He was thus alarmed that free-soilers were moving toward creating their own alternative government. The legislature, meanwhile, was determined to declare this move illegal and crush them.

Free-soil New Englanders met in Lawrence in August, 1855, and Dr. Charles Robinson, thanks to his July 4 picnic speech a few weeks earlier, emerged as their leader. Remember: Kansas fee-soilers were already thinking of themselves as the heirs of American Revolutionaries in 1776, which is also how proslavery Kansans thought of themselves. Both sides were convinced they were being oppressed.

Free-soil New Englanders, meeting in Lawrence, and led by Robinson, declared the Kansas legislature illegal, and called for a constitutional convention that would meet asap, within two weeks, write a state constitution, and apply for statehood. In their view, this was an emergency. The convention would meet at Big Springs, a crossroads hamlet near Lawrence, and would include Midwestern free-soilers, who weren’t as enthusiastic about abolition as some of the New Englanders were. They all came to the convention armed to the teeth.

Free-soil Midwestern settlers (from places like Ohio and Indiana) were not abolitionists, but they were increasingly thinking on the same lines as the more anti-slavery Lawrence New Englanders. Exhibit A of this shift in thinking was Jim Lane, Kansas settler, Midwesterners’ leader from Indiana, and racist.

Lane had first tried to jumpstart the Democratic Party in Kansas, and persuade free-soil settlers to support the legislature. If that seems surprising, consider that Lane didn't care about the legislature passing laws declaring that abolitionists would be silenced or arrested: He wasn't an abolitionist, and he was a racist. Jim Lane opposed slavery in Kansas because it hurt non-slaveowning white people in Kansas, like Jim Lane. I'm assuming his support for the legislature was based on what the legislature had not done, which was that it had not yet made slavery official. But Lane now saw that, politically, his support of the legislature was not the way the wind was blowing.

Lane decided to compete with the abolitionist Charles Robinson to lead Kansas settlers in a grassroots campaign toward statehood. So he did an about-face, and by October, he was speaking against the legislature. Like I said, things were fluid.

Clearly, the free-soil movement was taking off in Kansas. And whether from the Northeast or Midwest, abolitionist or (much more likely) not, free-soil supporters in Kansas were pushing back against the proslavery legislature, first peacefully, but prepared to use violence if need be: They. Were. Armed. To. The. Teeth.

This does not mean that Lane and his supporters now became interested in abolition of slavery throughout the US. They weren’t. Or that they had decided to stop being racist: They had not. They hated African Americans even more than they hated slavery. At the Big Springs convention, the Midwesterners got the delegates to agree to support a future law preventing black people from moving into Kansas. Their biggest concern, true of almost all of the delegates, was to create an effective opposition to the Kansas legislature.

The delegates who came to Big Springs agreed to form the Free State Party, made up of men of different national party identities, and named to make clear that they weren’t abolitionists: Most didn’t care that slavery was established elsewhere. They only wanted Kansas to be a free state, and they only wanted people who lived in Kansas to vote on this. With a new election coming up for Kansas Territorial delegate to the US Congress, they took up ex-Gov. Reeder’s suggestion to pretend the territorial legislature didn’t exist, and send their own delegate to Washington DC.

Remember, only actual states can have senators and congressmen, so a delegate was the next best thing in Washington for a US Territory like Kansas. The Free State Party decided to nominate Gov. Reeder himself, even though, ironically, he had never moved his family to Kansas, and so, technically, he didn’t actually live there, even when he was Governor. Plus Reeder was a disgraced grifter. But he was also a free-soil celeb hero.

The Big Springs convention also agreed to meet again in September, this time in the town of Topeka. There, they agreed to set up an alternative government in Kansas, and to meet again in Topeka the following month, October, to draft a constitution.

This was all radical stuff, and the Free State Party leaders didn’t take it lightly that they were doing something dangerous, going against the official Kansas government. They were at great pains to point out that they had no choice. And they had to move fast, before the Kansas legislature and the proslavery men in Missouri had time to react and prepare. Too late. Missouri newspaper were already dubbing them “revolutionists” (read: crazy lefties).

The Free Staters decided to ignore the legislature’s election for the Kansas delegate to Washington DC, scheduled for the first Monday in October. They decided to hold their election the following Tuesday. The candidates were J. W. Whitfield, the proslavery incumbent delegate, and grifty ex-Gov. Reeder. This was a clear choice: Kansas with or without slavery. Kansas as an independent state, or Kansas as a colony of Missouri. I can imagine bumper stickers on wagons reading “Vote for the Grifter. It’s Important.” (Yes, I stole that, more or less, from a Louisiana election in which a crooked politician ran against a Klansman)

On the official Monday election day arranged by the legislature, Missourians again crossed the border into Kansas to vote, and some dropped by Lawrence to threaten the New Englanders with violence. The Missourians did not realize that the New Englanders were armed and ready for them: Fortunately for all, and thanks to everyone’s restraint, no violence broke out.

Unshockingly, the official winner for Kansas territorial delegate to Congress was the proslavery guy, Whitfield. Also unshockingly, Reeder won the following' week’s alternative election. Whitfield was declared to have the most votes, but, as you can imagine, the Free Staters made every possible objection to him, arguing he had not been elected properly. But, and this really did surprise me, most ultimately accepted Whitfield as the winner. So they weren’t quite as revolutionary as their opponents claimed. Or were they?

Meanwhile, the Free Staters were still planning their meeting in exciting exotic Topeka, Kansas, for two weeks starting in late October. There, they drafted a Constitution that sounded less like the calm and slightly boring US Constitution, and more like the shouty American Declaration of Independence of 1776, with lots of emphasis on the power of the people and their right to abolish their own government. They also agreed to keep slavery out of Kansas, of course.

And yet, the Free State Party delegates disagreed on a lot of things. Charles Robinson led the minority of radicals who wanted black people and white women to have the right to vote), while Jim Lane wanted free black people to be kept out of Kansas. The compromise? When the voters voted on the Kansas constitution they proposed, they would also vote whether to allow in black migrants. Even asking this question of white voters could be seen as a form of progress. No, hear me out: Voters would have to think about it, however briefly. Each voter would have to consider, however briefly, whether free black people could be considered Americans. And, if so, whether they would have the rights of Americans.

The Free-Staters’ biggest compromise in Topeka, however, as Charles Robinson noted, was putting white political rights before supporting the abolition of slavery. But they could at least agree on keeping slavery out of their proposed state. Again, it was something they could agree upon.

Put to a popular vote in December, 1855, the Topeka Constitution was approved overwhelmingly. Voters also agreed 3-1 to exclude free black settlers. This is your reminder that, despite this, the black founders of the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, would arrive 22 years and a Civil War later. Things change. Oh, and make that TWO civil wars. The first would be fought in Kansas.

They’re Not 'Armless

“That a revolution must take place in Kansas is certain . . . When farmers turn soldiers, they must have arms.”

—Amos Lawrence, Kansas settler and New Englander

When you think of white people in Kansas at this time, maybe you’re now thinking of a proslavery Missourian: Big beardy murderous-looking bloke with two pistols and a rifle, and a quart of whiskey at his side, chewing and spitting tobacco. You may not be entirely wrong, or you may be thinking of the Border Ruffians, hired voters. If you’re thinking of a Free Stater as a weedy little chap with a Boston accent clutching a Bible and looking scared, you may also be right. Or not.

Back in February, 1855, free-soilers had launched the Kansas Legion, a combination fraternity (UK: Like freemasons) and army. They used secret handshakes, passcodes, and black ribbons attached to their shirts to identify each other, as well as signing by rubbing an eye with the left pinkie, which must have led to some tricky misunderstandings. The Kansas Legion’s goal was to make sure Kansas became a free state, and, quoting them here, “to protect the ballot box from the LEPROUS TOUCH OF UNPRINCIPLED MEN”.

Speaking of unprincipled men in Kansas, or at least a man with flexible principles, consider an ordinary guy named Patrick Laughlin who joined the Kansas Legion. He was an Irish immigrant, who had started out as proslavery, but was so shocked by the shambolic elections, he became a Free Stater.

However, Patrick Laughlin, it seems, was deeply shocked by violence, which seems a bit odd for someone who had joined a paramilitary group by choice. He saw a delivery to the Kansas Legion of boxes marked “Dry goods” (which typically meant products like cloth), only to see them opened to reveal rifles. He was also shocked to hear George Brown, editor of the Herald of Freedom, talking about fundraising for guns among supporters in the East.

Laughlin was so appalled, he went back to supporting the proslavery side, and, no, I don’t get that either, except to say that he maybe had a very rosy view of what slavery was, OR, more likely, didn’t care about the enslavement of black people at all, but did worry about law and order. Or getting in trouble. Or something.

Laughlin now spilled the beans to proslavery men on what he had seen and heard as a member of the Kansas Legion. Later, to show how much he objected to violence, Laughlin murdered a free-state man who had confronted him about his shifting loyalties.

The Kansas Legion wasn’t the only free-state group preparing for armed conflict. Rifles began pouring into Kansas, starting in May 1855, and continued through most of the following year. Among the major New England donors who paid for rifles, ammo, cannons, and a howitzer, were thugs like pioneering landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (who later designed parks including Central Park in New York City, and parks in Atlanta) and abolitionist clergyman Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (father of recent bestselling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, also a popular stage play, which was as close as you got at the time to making a major motion picture out of it).

Students at Grinnell College, founded in Iowa by devout New England Congregationalists, descended from Puritans, clubbed together to buy fifteen rifles, and, Dr. Etcheson coyly notes, “perhaps thereby began [Grinnell’s] long tradition of supporting radical causes.” Yup, Berkeley in the cornfields, that’s Grinnell.

NEEAC (the New England Emigrant Aid Society) claimed not to be funding weapons for Kansas, but that was a total and utter lie. They sent, for example, a hundred rifles in boxes labeled “books”, maybe the most New England disguise ever, and figuring that this would deter illiterate Missourians from any interest in the contents. Eli Thayer, director of NEEAC, personally donated $4,500 for weapons and ammo, while claiming that NEEAC “do nothing of this”.

Oh, and Free Stater J. B. Abbott returned from a weapons-gathering mission in the East with the blessing of Amos Lawrence, who wrote him a letter of introduction. He brought in rifles, a howitzer, shells, hand grenades, rockets and (for that romantic 19th century touch) swords. Abbott boasted that news of how well-armed the free staters were had already convinced a half dozen proslavery settler families to flee Kansas. Abbott and other free staters made the weapons sound a bit like how in the 20th century we decided to think of nuclear bombs, only intended to deter the enemy, but not to actually be used, which always sounds very optimistic about how reasonable every individual person involved can be expected to be.

Dr. Etcheson writes, “But clearly the free-soil movement now sought to do exactly what free staters condemned the proslavery party for doing: achieve its ends by the threat of violence.”

Yup. But violence wasn’t the only way to go. Now, proslavery men were keen to win the propaganda war, and were presenting themselves as the forces of law and order. Meeting at Leavenworth, they formed the Law and Order Party and accused the Free Staters of sowing “anarchy and confusion” by denying the authority of the legislature (which, just to remind you, was elected by proslavery forces in anarchy and confusion). And then, meeting again in November, the Leavenworth group accused the Topeka (Free State) movement of treason and rebellion.

Free state men saw themselves as revolutionaries, rising against tyranny in defense of their voting rights. Proslavery men, afraid of losing their rights to property (in people) saw them as rebels against lawful authority. Anything at all could be seen as political, and trigger open conflict. And anything did.

Bits of Violence

One of these anythings that triggered violence was an argument over who owned a bit of land in Hickory Point, Kansas, a free-state settlement. White men from Indiana had claimed the land, and, as land speculators, not done anything with it, intending to make a profit without actual work. It suddenly occurs to me that this “not doing anything with the land” argument was used for shoving American Indians off their land, but I digress, because arguing against this only works when those who hold the land and don’t do anything with it are white and/or land speculators.

So a proslavery settler called Franklin Coleman moved onto the land the Indiana men didn't use. Since he didn’t have a formal claim, this made him a squatter. The Indiana landowners, however, now sold this same land to another guy from Indiana, Jacob Branson, a free-soiler. Branson notified Coleman of his ownership, and gave him notice of eviction. He then tried moving into Coleman’s house, but Coleman waved a gun at him.

Branson, however , also had a gun. And he now invited others to come live on his land, like Charles Dow, a fellow free-soiler. When Dow was returning home one day, he ran into Coleman, who shot and killed him. Coleman claimed self-defense, saying that the two had gotten into an argument, and Dow had physically threatened him. Convinced he could expect no justice in a free-soil settlement, Coleman fled to Missouri.

An argument over who owned a bit of land would, before now, have simply been understood as what it said on the tin: An argument over who owned a bit of land. Now, however, in Kansas, this small conflict would be given new significance as a confrontation between the two sides, free state and proslavery. First, though, people had to frame it as a political issue. That happened immediately.

Local settlers in Hickory Point, mostly members of the local free-state militia, met and formed a vigilante committee to hunt down Dow’s murderer or murderers. Some had already taken justice into their own hands: They threatened witnesses, burned down the home of two proslavery families, and ordered other proslavery men and women to get out of their houses. The group then torched Coleman’s abandoned house.

Now the authorities arrived in the form of a posse of men led by Samuel Jones, who just happened to be (a) Local proslavery leader and (b) Sheriff of the county. He arrested Jacob Branson.

Sheriff Jones, with Branson as his prisoner, went in search of other culprits and he found them, in the form of fifteen members of the local free state militia who blocked the road he was on. One claimed to be Branson’s attorney, and when someone nervously suggested that the Sheriff and his men might shoot, said, “Let them shoot and be damned! We can shoot, too.”

Arguments continued for about an hour, without shooting, until the Sheriff ordered his men to leave, and without Branson. The free-state militia hustled Branson to safety in Lawrence, the free state stronghold, and to leader Charles Robinson’s home, no less.

Lawrence men held an impromptu nervous meeting at which, Robinson later reported, they were at least as worried about the potential threat to the town as about Branson’s fate. Hard to blame them. They had not invited him to take refuge in Lawrence.

Sheriff Jones reported the incident to Governor Shannon, who called out the territorial militia. Later, Gov. Shannon asked the commander of the US Army in Kansas for assistance from his professional soldiers (didn’t happen). He also notified the President.

Gov. Shannon was well aware that Kansas was on the verge of civil war, but he didn’t help matters by calling for Kansas men to help Sheriff Jones fight the men who had rescued Branson.

Now, a thousand proslavery Missourians, including college students as young as sixteen, and a grandfather with his son, grandson, and the ancient flintlock his father had used during the American Revolution, grabbed their guns, and headed for the Kansas border, into an emerging state in which they didn't live, to rescue the cause of slavery. Not states’ rights. Slavery. Take note.

More violence threatened, but by whom? As Missourians headed in the direction of Lawrence, free staters converged in the town. One man wrote in a letter to this wife that there were 2,000 men ready to fight in Lawrence, and about the same number of Missourians waiting to attack them. He told her he wasn’t sure he would survive.

At night, free-state men crowded into every house in Lawrence (there weren’t many places to stay). During the day, they dug four or five earthworks for defense, seven feet high and a hundred feet around, connected by trenches. Women filled cartridges with gunpowder and ammunition, and practiced shooting. But the free staters weren’t exactly spoiling for a showdown. A lot of people in Lawrence blamed Jacob Branson for the peril they were in, and within two days, not being popular, he quietly left town.

In an effort to avoid violence, free-state leaders opened negotiations with Gov. Shannon, and contacted the President. While Missourians blockaded Lawrence, some arms shipments were still smuggled into town, including a howitzer (modern cannon) stashed in a packaged buggy. When the buggy got bogged down in mud, a group of passing Missourians, unaware of its contents, helped the owner free it. Aside: Reminds me of a liberal young friend who got lost on a deserty trail, and was rescued by lads of his own age wearing “Let’s Go Brandon” (anti-Joe Biden) shirts. They were very kind, and insisted. I’m not sure they didn’t realize he was a liberal, either.

Two women from Lawrence, Lois Brown and Margaret Wood, smuggled rifle caps and cartridges in their dresses and underwear, handing off other ammo to a nine-year-old boy who hid them in his trousers, and traveled separately.

The women and the boy were all stopped by Missourians, and the boy was searched, but Dr. Etcheson points out that, while free state propaganda depicted Missourians as scum who, if they broke into Lawrence, would rape every woman and murder all the men, the Missourians who stopped the three arms traffickers on the road were civil to them all. “The Missourians did not make war on women and children,” Dr. Etcheson writes, “even when women and children preparing to make war on them.”

Darn it. Look, I don’t want to give proslavery Missourians any credit for being human. I want to hate them. Interlopers on behalf of slavery? Yes. People who corrupted elections then demanded everyone bow down to the phony legislature they “elected”? Yes. But maybe not as murderous as we or the free-staters thought, or more violent than the free-staters? Huh. Grumble. OK, maybe.

Before you suspect Dr. Etcheson of being an agent for the Daughters of the Confederacy, may I remind you that she’s a historian? This is why we don’t get invited to parties. We don’t just tolerate information coming to light that messes with our heads, our preconceptions. We feel a little taken aback, we think about it, and then we welcome the news with a weird glee, we say “Ooo!” whenever things don’t turn out to be tidy. We insist on pointing to surprises, contradictions, complications. The American public (love you, mwah 🥰) has a very hard time with this sort of thing. No wonder, when history teaching is so often so very bad, so very black and white, so all about memorizing, and not about discussing and thinking, and not the gray it should be.

If, regardless of your politics, you’re taking your history from someone who only writes stuff that gives you warm uncomplicated feelings, and it’s all terribly straightforward? That’s not history. And it doesn’t prepare us at all for reality.

Having said all that, invading Missourians did not treat free state men so carefully as they did women and children. In December 1855, a proslavery patrol made up of Missourians, officials, and Kansas militia, came upon three men coming home from Lawrence. The travelers were brothers Thomas and Robert Butler, and their brother-in-law, Thomas Pierson. Two of the Missouri men, including one called George Clarke, interrogated the three about where they had been, and about the situation in Lawrence.

Thomas Barber asked Clarke why they were being stopped. Clarke responded by instructing Thomas to come with him. When Thomas Barber said no, Clarke drew his gun. Robert Barber now tried to draw his own pistol (which his brother had earlier asked him not to carry) and got it caught in the holster.

Clark shot at Thomas Barber, who did not carry a gun. Clarke, his colleague, and Robert Barber now shot at each other, but didn’t hit.

The three men from Lawrence galloped off, soon pursued by the proslavery patrol. But Thomas fell off his horse: Clarke’s first bullet had hit him in the abdomen.

Pierson, the brother-in-law, wanted to surrender to the Missourians, but Robert Barber thought they would be killed if they did, and since his brother was dead, suggested the two of them get away while they could. They galloped off, leaving Thomas Barber’s body behind.

Thomas Barber was, in fact, still alive. A woman from a nearby house brought him water where he lay, but he was unable to drink, and forty minutes later, he died.

Is This It, Boys? Is This War?

In Lawrence, Charles Robinson soon got the news about Robert Barber, and tried to keep it quiet. He didn’t want to trigger anger among his followers, especially because he might not be able to control them.

Governor Shannon, meanwhile, was worried that he could not control the Missourians whom he (technically) commanded.

So Shannon invited Robinson and other Lawrence leaders to meet with him. From them, he learned they were terrified that the Missourians would wipe Lawrence off the map.

Now Gov. Shannon, wearing his diplomacy hat, set off on a tour of Kansas with heavy support: Together with proslavery Senator Atchison of Missouri, and Albert Boone, the Missourian grandson of the late American celebrity hero Daniel Boone, Shannon visited the Missourians’ camp for discussion. The three men then went into Lawrence, to meet with the free state leaders at the Free State Hotel.

As they arrived in the hotel’s conference room, Gov. Shannon and his companions were shocked to see the corpse of Thomas Barber laid out in a room across the hall. Awkward.

They spent the day in Lawrence, at the end of which Gov. Shannon had dinner with Charles Robinson, and assured him of his concerns over Thomas Barber’s death and the Missourians’ aggression. A Lawrence committee then drew up a written statement of what they and Gov. Shannon had agreed. That same night, Shannon persuaded members of the Kansas militia not to attack Lawrence. That’s quite an impressive day’s work for an “old fogy” as Shannon had first been described!

The negotiations continued the following day between Albert Boone and Sen. Atchison, representing the Kansas Territory government, and Charles Robinson and Jim Lane for the free-staters. Within five hours, they had signed a joint statement: Lawrence’s citizens were not held responsible for rescuing Jacob Branson, and they promised to cooperate with the law in the case of any future criminal investigations, although, as Atcheson notes. they made it clear they didn’t accept the legitimacy of the Kansas legislature or its laws.

Both Gov. Shannon and the free-state leaders continued to worry for the safety of Lawrence, and no wonder. Two thousand Missourians still surrounded Lawrence. And this was not a disciplined professional army. Many Missourians did indeed want to destroy Lawrence and its newspapers, and to capture the town’s weapons stash.

However, Sen. Atchison, even though he was a hawk compared to Shannon, thought that the agreement made the proslavery side look good to the American public, and that an armed attack on Lawrence would waste that propaganda advantage.

Gov. Shannon ordered the Missourians to disband, and a lucky winter storm helped persuade them to go home. There was much celebration at the Governor’s house, and over in Lawrence. A ball at the Free State Hotel was hosted by the ladies, and among the invited who showed up was— get this—Sheriff Jones, the proslavery county sheriff who had arrested Jacob Branson. The free-soil New England ladies of Lawrence were much impressed by the Sheriff’s good manners.

Celebrations extended to the US North, where people admiringly noted how the Lawrence men had stood up for themselves. See? Yankees weren’t wimps! Lawrence had shown the South that Northerners were made of steel! And they had stood up against the forces of slavery, which threatened freedom throughout America!

Not shockingly, many white Southerners held a different view of what just happened in Kansas. They saw what was now being called the Wakarusa War (even though it had stopped short of war) as a victory for lawlessness, and they felt let down by the Missourian “border ruffians”, who had embarrassed the South by allowing the Lawrence men to “win”. Yet other Southerners worried that the Missourians had overstepped, especially in the murder of the unarmed Thomas Barber, who was buried a free state martyr.

On the day of the celebrations, a slightly drunk Gov. Shannon, who had been pre-partying, was surprised to find Charles Robinson at his door. Robinson reported that the Missouri men— still outside Lawrence at that moment—had threatened to invade, and asked him for permission to fight back. Gov. Shannon signed the document Robinson shoved at him. This piece of paper allowed the free staters to remain an organized military force, on alert, and ready to fight.

In fact, Robinson had lied to the Governor. There had been no threat from the Missourians.

Shannon wrote to President Franklin Pierce, warning him that amateur militiamen and volunteers (the Missourians) could not be expected to be peacekeepers. Shannon wanted the President to authorize him to alert the US Army, if necessary, to keep order in Kansas. President Pierce, however, declined to step in at all. Things in Kansas were in hand, he declared to the American public. Uh huh.

This Is It, Boys. This Is War.

The people of Lawrence spent the stormy winter of 1855-6 wrapped in buffalo robes, huddled by their woodburning stoves. Occasionally, they popped outside to practice their shooting skills. Since shooting ranges with printed paper cutouts of outlines of people were a thing of the future, they shot at pictures of Sen. David Atchison.

The Lawrence people knew the Missourians were determined to make them bow to the territorial legislature. While Charles Robinson and other free state leaders wanted to stick to non-violence, this was not the view of everyone in Lawrence.

The goals of both the free state and proslavery sides were political, Dr. Etcheson writes, But when they turned to force to achieve them, the result was Bleeding Kansas, the title of Etcheson’s book, and the name given to what happened next.

Missourians on the Kansas border felt disappointed and disgraced by the result of the Wakarusa “War”. Now another election was coming to Kansas, another chance to bring the free starters to heel.

Wait, what election, Laing?

Okay, cast your mind back to before the Wakarusa Non-War, when the free staters met in Topeka, and concluded that their only choice to oppose the proslavery legislature was to write a constitution (which they did) and form an alternative government.

Now, January 15, 1856, there was to be an election for officers for that government, which gave everyone something to talk about while they froze in their homes that winter.

In Leavenworth, a proslavery stronghold, the mayor had banned voting in this alternative election organized by the Free State Party. So free-state voters instead set up polling places in homes, and waited three days to vote, trying to head off violence.

It didn’t work: Proslavery men threatened wannabe voters and their ballot boxes. But I don’t want to sound like a textbook here. What did this look like on the ground?

After voting, Stephen Sparks, his son Moses, and his nephew, set off for home from Leavenworth. Passing Dawson’s store, the three men were surrounded by Missourians who threatened them. As it happens, Stephen Sparks, although a free-stater, was from Missouri, and he appealed to the men to be respectful to a fellow Missourian.

What Stephen Sparks didn’t know was that a proslavery group of militia men who called themselves the Kickapoo Rangers (taking the name of a Native people) had already visited his house while he was out voting. They had pointed a gun at his twelve year old son, and issued his wife with a written warning to pass along to Stephen, ordering him to leave the community-as Dr. Etcheson points out, the same community whose members he was now trying to appeal to on the road outside the Dawson store. The men shot at Stephen and Moses Sparks. Moses managed to get away, and ran back to the polling place for help.

Free-state men quickly organized a rescue party, led by Reese Brown, a man with experience defending Lawrence, but who was currently drunk along with his mates. They managed to free Stephen and the nephew, and all returned to Leavenworth, but shots had been fired, and one had hit a proslavery man named Cook.

When Reese Brown and his buddies tried to go home the next morning, they were arrested by a proslavery company of Kickapoo Rangers, led by a man named John Martin, and charged with shooting Cook.

As Martin, his men, and his prisoners approached Dawson’s store, which Martin planned to use as an impromptu jail, he began to lose control of his men. They were drinking. One of them, Bob Gibson, started hitting one of the captives with a hatchet, while his proslavery comrades and the free staters tried to stop him. In the store, they found Cook dying on the floor, moaning loudly. This did not improve the mood of the Kickapoo Rangers.

While Martin questioned Reese Brown in Dawson’s store, his men twice broke into the room. The second time, they were led by Gibson, the lieral hatchet man, who chopped at Brown in what was clearly becoming his signature move.

Martin left the room, quickly told the free state captives he had lost control of his own men, asked them to pop their names on a bit of paper, and then urged them to run like hell, while Brown was being beaten up by twelve men plus Gibson.

The Kickapoo Rangers soon realized this was not a fair fight, and decided that Brown and Gibson should instead fight each other. But Brown was bleeding heavily from a hatchet chop to the head, so I’m not entirely sure how that was fair, but whatever: Brown apparently reached the same conclusion, because he tried to make a run for it.

Apparently deciding enough damage had been done, the Kickapoo Rangers took Reese Brown home, and dumped him on his own doorstep, where he was found by his wife and toddler daughter. The neighbors fetched a doctor, but Brown was beyond medical help. His last words: “They murdered me like cowards.”

Otherwise, it was an uneventful alternative election on January 15, and Charles Robinson was elected alternative governor. But the murder of Reese Brown put a damper on any celebrations. Worse, US President Franklin Pierce issued a public special message (today, it would be on TV) in which he declared that the proslavery Kansas territorial government was the real one. He blamed the election on New England abolitionist propaganda, and labeled the Topeka movement a fake. He then threatened to set the US Army on the free-staters.

These were the sort of moves that routinely put Franklin Pierce on lists of “crappiest presidents ever” and “most utterly forgettable presidents,” and why there’s a pretty good chance you never heard of him before now. The new free-state attorney general described Pierce in his diary as a “ninny”.

Now that Pierce had made his position clear, the free staters, far from being dismayed, reacted with defiance, even as proslavery newspapers argued that the new alternative government was treasonous, and should be prevented from meeting. The free-state government did meet, though, gathering in Topeka. Sheriff Jones stood by with a clipboard, writing down their names. Everyone expected them to be arrested.

Regardless, Charles Robinson made his inaugural speech in which he called for an organized militia (as opposed to the disorganized volunteer kind that could easily get out of hand). He asserted that his was the real government, based on real popular sovereignty, because free staters were the majority among actual settlers in Kansas.

Robinson also called for the proslavery territorial administration to be suspended, and for Kansas to be admitted to the Union immediately. And he accused President Pierce of being complicit in “squatter sovereignty” , of supporting the Missourians who only came to Kansas to vote, harass, threaten, and abuse actual Kansans. Robinson made a nonviolent moral argument, and declared that the free-staters would not physically resist the US Army.

The free staters, keen to avoid appearing traitorous, moved carefully. Their alternative legislature passed laws, but said they would not be enforced until Kansas became a proper state.

But the proslavery forces were now deeply alarmed. Clearly, slavery and the government that supported it in Kansas were in deep trouble. Sen. David Atchison warned Amos Lawrence that the free staters “are the aggressors upon our rights. You come to drive us and our “peculiar” institution[slavery] from Kansas. We do not intend, cost what it may, to be driven or deprived of any of our rights.” Atchison made clear his view that free staters, just by migrating to Kansas, were attacking the white Southern right to slavery.

Missourians now harassed people who were on their way to Kansas. People like William Clark, traveling by steamboat, who managed to create a kerfuffle at an on-board bible study group. He told the group that Genesis showed that all “races” started with Adam and Eve.

This reasonable suggestion led his fellow Christians to immediately label Clark an abolitionist. He admitted to them that he believed Kansas should be a free state. Nobody actually said anything scary, but Clark decided it would be best to lock himself in his cabin with a good book for the rest of the day.

The next morning, it became obvious that offense had been taken: During breakfast, another passenger hit Clark with a chair. The boat’s captain decided to kick off the unruly passenger: Clark himself.

He was supposed to be ejected at the next town, but, afraid that the proslavery passengers might stand on deck and point him out to locals as an “abolition Yankee”, Clark jumped ship while the boat made a quick stop for fuel (wood, in case you’re wondering).

This wasn't all. Missourians searched packages addresessed to Kansas. Stagecoach drivers in Missouri dumped mail they didn’t like the look of. But before we think they were paranoid, weapons were headed for Kansas: Nine boxes of rifles were found on board a steamboat on the Missouri River.

Clubs encouraging proslavery Missourians to move to Kansas were hastily formed and started fundraising, warning Southerners that what was happening in Kansas could lead to the end of the United States, or slavery itself. Soon, Kansas settlement clubs were springing up throughout the South, in places like Gainesville, Mississippi and Macon, Georgia. They weren’t wrong in their forecast, as we can see from, um, the Civil War, but that's getting ahead of the story.

But while some Southern state legislatures considered using tax money to aid Kansas migration, none did. And very few people from the Deep South actually moved to Kansas. It didn’t help when proslavery settlers sent home letters saying things like “Kansas Territory is worse than nowhere, and has been greatly overrated.” (Yes, that’s a quote)

Meanwhile, Northern migrants continued to pour into Kansas. Yale students and professors funded the purchase of rifles for a group of migrants leaving Connecticut. And one free-state man in Kansas advised other New England migrants to “come thoroughly armed with the most efficient weapons they can obtain and bring plenty of ammunition.” His name? John Brown, Jr.

No, not that John Brown. His son.

Now Congress spoke up. A Senate Committee on Territories, led by Democratic Party leader, Illinois Senator, and political toast Stephen Douglas, still desperately trying to hang on to his leadership role in a party of angry white Southerners. The majority on his committee, Democrats, firmly sided with the President and against the free-soil Topeka government.

Douglas blamed NEEAC for everything, and called for a new constitution to restore order in Kansas, plus admission of Kansas to the union under the current proslavery government.

The minority on the committee (Republicans, but forget the modern labels, ok? They don’t help) issued their own very different report, supporting the Topeka Constitution and movement. Like other Republicans, they believed that, in Kansas, white men’s rights were being crushed to support slavery.

Republicans in Congress moved to admit Kansas to the United States under the free-state Topeka Constitution. Senator William Seward spoke in Congress, comparing the Kansas free staters to the revolutionaries of 1776, and portraying President Pierce as pretty much the King George III of the moment, the tyrant preventing a free Kansas.

Democratic Senators pushed back. Heated words happened. But this spat was nothing compared to what happened next. And I’m betting this next event will ring serious bells with my US readers, who get so excited when you remember stuff from high school history, I don't want to rain on their parade.

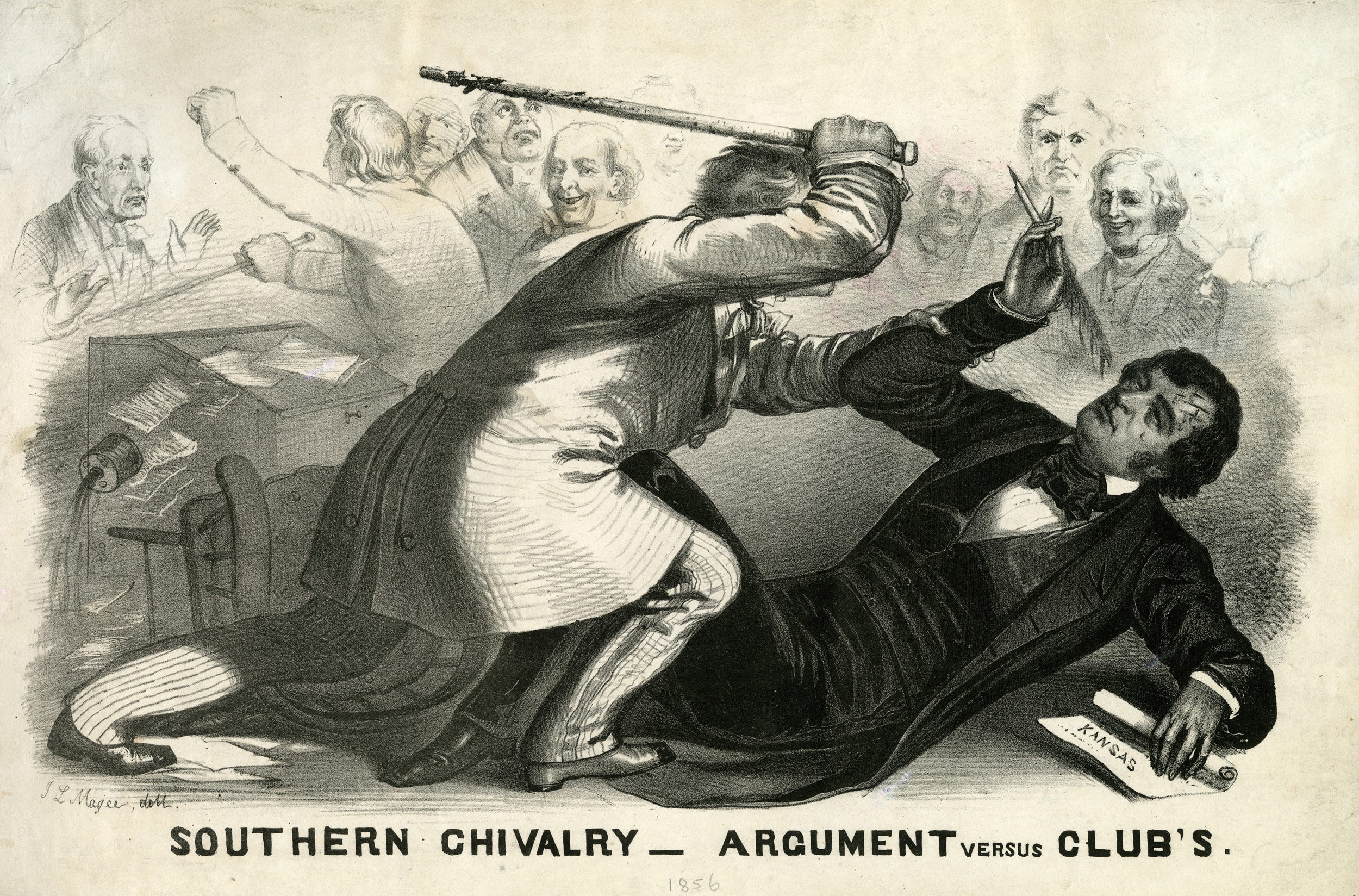

Assault in the Senate

Massachusetts Republican Senator Charles Sumner was fed up with the delay in admitting Kansas to the US under the free-state Topeka constitution. So fed up, in fact, he gave a speech lasting two days. He blasted the South for its “depraved longing” for Kansas to be a slave state, for the taking of Kansas by force as the “rape of a virgin territory”.

And if you think that was strong language, consider what Sumner said about his colleagues in the Senate. He described Senator Stephen Douglas as a “noisome [stinky], squat, and nameless animal.” Ouch.

Sumner didn't spare the feelings of Senator Andrew Butler, an elderly slavery-supportin’ Good Ole Boy from South Carolina, who was seen as nice by his colleagues. Sumner dismissed Butler as an upper class snob who acted all high and mighty in defense of slavery. Sumner portrayed slavery as Butler’s tarty mistress.

Douglas condemned Sumner’s language, and especially his attack on “the venerable, courteous, and the distinguished Senator from South Carolina.” Hoo, boy, this sounds familiar to me after the decades I spent in Georgia: No matter how evil a powerful white Southern bloke might be, nobody is supposed to insult him or call his character into question, because he's nice to friends, family, fans, and people who know their place. Puhleeze. Right now, I’m rooting for Sumner despite knowing that this isn’t going to end well for him.

Three days after Charles Sumner’s speech about Butler, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina, Senator Butler’s cousin, walked into the Senate chamber, and came up behind Sen. Sumner, who was sitting at his desk, working.

Rep. Brooks raised his heavy walking stick, and repeatedly hit Sumner over the head and shoulders. Sumner, taken by surprise, could not get up and defend himself: His knees were trapped under the fixed desk. In his desperation, he wrenched the desk from the bolts holding it to the floor.

It took a while before other senators took in what was happening in front of them, and rushed to Sumner’s aid. By then, the Senator had serious injuries, and he couldn’t work afterward for two years. Massachusetts people honored him by re-electing him anyway, even knowing he couldn’t represent them in Washington DC.

Preston Brooks resigned, but South Carolinians re-elected him anyway, and many sent him walking sticks to replace the one he had broken on Sen. Sumner’s head. One was inscribed “Hit him again.” Har. Har. Har. Charming.

While New Englanders were shocked by this violence, white Southerners reserved their anger for Charles Sumner, who, in their view, had dishonored Senator Butler, and got what he deserved. That, friends, is Southern “honor culture”, and the rest of us look on agog.

Who Shot The Sheriff?

Fights in Congress were surprisingly common, like politicians were ice hockey players or something, but this one seemed to Northerners to be beyond unacceptable, and I trust we can see why. Plus people were concerned that Brooks’s assault would put a chill on free speech and open debate, and perhaps we can understand that concern, too. Hold those thoughts.

Meanwhile, Southerners accused Sumner (yes, Sumner) of being a coward (um, hello, he was sitting at his desk with his back to Brooks when he was violently attacked), and also of faking his injuries. Um, no.

Brooks they praised for “coolness and courage”. I can't help noticing this was exactly the kind of language that Southern newspapers, decades later, used to describe white men who slowly tortured black men to death in the name of “justice” at horrific public lynchings.

Meanwhile, back in Kansas, the proslavery government was asserting its authority. Sheriff Jones came to Lawrence and tried to arrest S.N. Wood, one of the men who had rescued Jacob Branson. Jones was prevented from his task by the crowd that gathered in Lawrence, and he left town without his prisoner. He tried again the next day, with a few helpers, and with the same result.

Third try was the charm: This time, Sheriff Jones brought US soldiers on horseback for support. While the crowd booed and yelled insults, they did not resist the US Army, and the sheriff arrested six men. But he did not find S.N. Wood. So Sheriff Jones camped outside Lawrence, intending to continue his investigation.

Late that night, as the Sheriff sat in his tent, someone shot him in the back.

The proslavery media went wild. One headline read simply “TREASON!!!” Others blasted the Sheriff’s “murderers” as traitors and abolitionists.

In fact, Jones had not been murdered. He wasn’t dead. But the shooting threatened to push Kansas over the edge into civil war. Free-state leaders, eager to prevent violence, condemned the shooting, labeling it the work of a lone gunman. Charles Robinson even claimed that proslavery forces had deliberately shot the sheriff to push the moment to crisis, especially because a committee of congressmen had just arrived in Lawrence to assess the situation in Kansas.

The Congressional committee, not surprisingly, found proslavery witnesses reluctant to show up in Lawrence.

Delegate Whitfield (yes, the proslavery dude who went to represent Kansas in Washington, DC) eager to help, now dropped by proslavery town Leavenworth to chat with people there.

However, the Committee, which interviewed people for ten hours and more every day, found the free-staters’ version of events most believable.

The proslavery Kansas government was not impressed: A judge now ordered a grand jury to indict free-state officials and close the newspapers and Free State Hotel in Lawrence. This was indeed a crisis.

The Flight of the Governors

Free-state Gov. Charles Robinson was sent east to get help, while former Gov. Reeder agreed to be arrested to draw attention to what was happening in Kansas.

When a marshal showed up with a warrant, however, Reeder appealed for help to the Congressional committee. They didn’t think it was their job, so they refused to assist. Rather than bravely be arrested, as planned, Reeder now fled Kansas in disguise, staying at safe houses during the day, and walking at night. Charles Robinson and his wife, Sara, meanwhile, were headed by steamboat in the general direction of faraway Washington DC. But as the boat passed through Missouri, Robinson was arrested, and sent under guard to Leavenworth. His guard in Leavenworth? Our friend Captain Martin of the Kickapoo Rangers! The same guy who had failed to save the life of his last prisoner, Reese Brown from his own men!

Luckily for Charles Robinson, he survived Martin’s care. And Mrs. Sara Robinson, who had not been arrested, made it all the way to Washington DC, where she handed documents from the Congressional committee to Republican politicians.

It's all terribly exciting, that story. I half expect John Wayne to turn up. And it gets better. A posse led by a federal US marshal, and aided by Sheriff Jones (who was feeling a bit better after being shot), assembled without the knowledge of Gov. Shannon. The posse entered Lawrence to arrest more free state leaders, while hundreds of Missourians surrounded the town, and gave every impression of preparing to invade, including shooting their guns in the air.

Fearing mass murder, terrified Lawrence citizens prepared to surrender to the Kansas Territorial government. When Sheriff Jones demanded their weapons, the city’s representatives meekly handed them over. Jones then led his men in destroying the Free State Hotel, which they suspected of being a fort, the same hotel where, months earlier, Sheriff Jones had impressed the ladies of Lawrence with his good manners.