The Water Is Wide. I Cannot Get Over.

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Luxury Palace Where Rich and Poor, Men and Women, Swam Side by Side, Yet Far Apart

How Long Is This Post? About 3,000 words, or thirteen minutes, plus photos

Dear Nonnie Friend,

“Wow, here’s an amazing museum, it’s only open one day a month, and tomorrow is it. That’s nuts. I can’t believe we’re here for the right day.”

I showed my phone to Hoosen, my long-suffering spouse. It was May, we were sitting in our painfully hip yet badly designed hotel room in a huge renovated Victorian building in Manchester, UK. Our room had a see-through loo and double bed that was accessible only from one side (no kidding, think about that). We had less than two days to explore this hardscrabble former industrial powerhouse of a city, which, like our room, was pretending to be hip, largely by building chain restaurants, expensive shops, and an IMAX in its downtown area.

I prattled on. “Trouble is, I don’t know if we can do this and Mrs. Gaskell’s house. It’s only open from ten to three. And Mrs. Gaskell’s the priority. Still, it does have a 1 p.m. tour, so maybe . . ?”

Hoosen, being an obliging bloke, or maybe just one who likes peace, agreed.

Did you catch our visit to the very cool home of author/mother Elizabeth Gaskell?

Writing Life at Home

Elizabeth Gaskell: Busy mum, activist, and bestselling novelist. She writes on her laptop while the kids play at her feet. She worries about the dangerous and unhealthy city on her doorstep, and the people who live in it. Her editor is Charles Dickens. Come meet her.

Now I looked at Google Maps and realized, to my joy, that we didn’t have to choose. “Looky”, I said, “It’s less than a ten minute walk between them!”

Sorted. We were very lucky to be in Manchester on the only day the museum was open that month. Which is weird, now I think about it, because, in its heyday, this other destination was a huge attraction in Manchester, open every day. and patronized by thousands.

So let me stop being mysterious, and tell you where we were going:

The greatest public swimming pool in Britain, ever.

But this is Non-Boring History, not the Guinness Book of Records, Ripleys Believe It Or Not, or Trivia-R-Us. So of course there's more to it than that.

Victoria Baths (to give it its proper name) was built in 1906, and that matters: In academic history, context —when and where something happened, and what else was going on at the time — always matters.

This massive building, which you can see at the top of the page (and it’s much bigger than it looks) was built starting at the very end of the 19th century, and opened in 1906. That was the time when the gap between rich and poor in Britain (and America, for that matter) had never been wider.

So who on earth was this luxury water palace for?

Wait for it. . . .

Everyone. Victoria Baths was for everyone.

Just not in the same ways.

A quick note for American readers: Swimming in Britain was called bathing, and swimming pools were called swimming baths. Which seems weird, but bathing doesn’t have to mean slathering yourself with soap and working on getting clean: Think of sunbathing. See?

Visiting the Swimming Pool Without Swimming

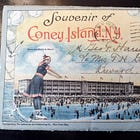

The early 20th century on either side of the Atlantic is a world we normally see only in black and white photos and film, or imagine in shades of brown: People dressed in earth tones living in an earth tone world, of factories, smoke, and grim rows of housing, and that’s not just a myth because of the photography. This was an increasingly secular society, too, one in which fewer and fewer Brits went to church, the place where you traditionally saw lovely splashes of color in stained glass. At the turn of the last century, the churches where people gathered, regardless of religion or lack thereof, were more likely places of entertainment, which came in Technicolor before Technicolor was invented, places like Coney Island, in New York:

Victoria Baths, as we’ll see, is the same idea.

The next day, Hoosen and I entered the museum as directed, as you do, via the door that leads to the ticket sales and gift shop.

But let’s not do that. Let’s start at the top, shall we? Let’s enter in style, at the other end of the building, past the 1906 ticket office, through the turnstile and heavy wooden door, past glorious stained glass, and up the grand original tiled staircase in Wizard of Oz green, all looking just as it did more than a century ago.

And upstairs, we meet the pool!

The pool is empty now, as the photo shows, but it’s not hard to imagine how it looks in 1906, when filled with water, and happy swimmers, or bathers, splashing about. I actually think “bathers” is the better word. They’re not just grimly swimming up and down, to burn calories and prolong their future stays in the Shady Pines rest home. They get plenty of exercise in everyday life, most of them, just getting around on foot, and perhaps aren't so fixated on prolonging life through healthy living (although, I admit, healthy living was also a bit of a theme at this time). For many, then as today, a swim is typically for fun and relaxation.

The pool and building are heated, so it’s lovely and toasty. Go on, have a splash!

Can’t you just imagine yourself having a bit of a dip here?

Or if you are a serious proper swimmer, imagine yourself swimming laps to the echoing roar of the crowd in the balcony on gala (competition) days! How amazing that this is a public pool!

Yeah, well, kind of. See, this pool was meant only for posh people. In 1906, entrance was very expensive. It was like going on a ten-minute space trip or Titanic ogling voyage might be for us today, or even a relative bargain, a visit to the now-defunct, $6,000 for two days Disney Star Wars hotel.

Even if you, a working-class or middle-class person, were daft enough and somehow able to pay a big portion of your paltry income for such an experience, there was an added wrinkle in 1906. You wouldn’t feel comfortable surrounded by local bigwigs of all kinds, even the boss of the cotton factory you very likely worked in. They dressed differently, spoke differently, and didn't even pretend to be your equals.

How did anyone in Manchester get so rich anyway?

Work of Many Hands

What generated a lot of the wealth we still see in Manchester’s grandest buildings was cotton. It came from the American South, because you can’t grow cotton in England: it’s just too soggy.

Raising cotton had been the work of enslaved people until slavery was abolished in 1865, at the end of the American Civil War, and just over forty years before Victoria Baths was built.

Since then, former slaves had not received the compensation they had been promised from the US federal government. There was a brief period of opportunity after the war called Reconstruction (blink and you miss it) that was quickly shut down by elite whites reasserting control. While many formerly enslaved people sought to find a way out, few had yet succeeded: Many were still tied to the land by family ties that were hard to break, by lack of education (although black communities and Northern missionaries were working hard to fix that), and by threats of violence. People were intimidated and attacked when they tried to leave places like Georgia and Mississippi.

With slavery gone, black people on cotton plantations got some control over their daily lives, working independently as sharecroppers. But that independence was an illusion, as they discovered when they were cheated by landowners, who sold food on credit and kept the accounts, and who lied to them at cotton harvest time.

Cotton’s wealth also owed much to the work of poorly-paid factory workers in Manchester, many of them still children by our standards in 1906.

But it was cotton wealth and the people who made it who paid for Victoria Baths.

This pool is very grand. And yet. How weird that there are changing cubicles on either side of it? Yes, all the cubicles have barn doors and curtains, but they seem oddly exposed. 1906 was a time that was more Victorian than the Victorians.

This a time when women still wore long dresses and sleeves. This was when women could only swim in the sea after first changing in head-to-toe swimsuits in cabins on wheels called bathing machines, that horses pulled into the tide, so women could slip into the water without notice.

Why was there less modesty at this pool? What’s up with people at Victoria Baths changing in such a public setting? Hmm.

Well, here’s your answer: This pool was intended only for men. Ah. Ah ha. And, no, you couldn’t gender identity your way out of that, not in 1906! No willy? No admission.

And, of course, even if you were a man, you almost certainly couldn’t afford it. Not happening. Thanks to Downton Abbey and whatnot, people love to identify with the poshoes on both sides of the Atlantic. Look at your family history (and I don’t mean the geneaology charts Aunt Ethel pursued doggedly in every possible direction until she located the one posh person with whom you share DNA) You’ll see how most people lived.

Victoria Baths, in 1906, was segregated, not by “race” or skin color, not so far as I’m aware, but by class and sex. This pool, to repeat, was for rich men only. Uniquely in my family, my great-grandad, then living in faraway Scotland, might have qualified. Nobody else got into this pool, including his wife.

A Diversity of Segregation

But if you’re neither rich nor a man in 1906 Manchester, you are, interestingly, not out of luck.