Writing Life at Home

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD To Manchester, England, the Home of the Industrial Revolution, and of Mrs. Elizabeth Gaskell, the Author Who Out-Dickensed Charles Dickens

How Long Is This Post? About 3700 words, or 18 minutes

Dear Nonnie Friend,

As I said last time, I have spent very little time in Manchester, but Manchester women have impressed me all my life. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Mrs. Lewis, a tiny but formidable character in two of my novels, hailed from Manchester.

Speaking of novels and Manchester women, I know that I read Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton at school, and, I think, also North and South, both revealing and critical of the horrendous conditions in 19th century industrial Manchester, with its smog, loud factories, and dire conditions for factory workers.

I most likely read Elizabeth Gaskell’s novels because my English teacher loved Victorian literature, and especially books written by women. I certainly watched North and South on TV, as well as Cranford, another televised version of one of Mrs. Gaskell’s novels. But it’s all been a long time.

When I was at school, she was always known as Mrs. Gaskell, as if she had no first name, and only her husband’s last name. Her real name was Elizabeth Cleghorn. Oh, and she wasn't originally from Manchester: She was from Down South, as they say Up North. She also did a better job of social commentary than Charles Dickens, if you ask me, not least because she was in Manchester, Ground Zero of the Industrial Revolution, unlike Dickens's stomping grounds in London and Kent.

Thinking of all this, I started to understand why her novelist friend and fellow resident of northern England Charlotte Bronte, and Charlotte’s talented sisters Emily (Wuthering Heights) and Anne (The Tenant of Wildfell Hall) had pretended to be men when they tried to get published, calling themselves by the slightly weird pen names of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.

I also understood why, a hundred and fifty years later, a novelist named Joanne Rowling called herself J.K. Rowling when she sent out her manuscript about a boy wizard to publishers.

Honestly, I think I should have called myself Alastair Laing, because I know for a fact that while more people are ok these days with reading women’s work, too many would still rather pay a bloke when it comes to writing. Thank you, my dear Nonnie Friend, for not thinking like that.

Mrs. Gaskell was published, and was read, but then judged by influential critics as a lesser writer because she lacked a willy, although she got points for trying, poor dear. She was certainly thought less worth remembering than Charles Dickens.

Elizabeth Gaskell died in 1865, the same year the American Civil War ended, and her husband outlived her for nearly twenty years. After his death, their two unmarried daughters lived on in the family home in Manchester, and after the last one’s death in 1913, there was an effort to save the famous author's house as a museum. That didn’t work out, because Elizabeth Gaskell was long out of fashion, and the house and household goods were all sold.

The home of Elizabeth Gaskell became the home of a businessman and his large family for the next 55 years. The house at 84, Plymouth Grove could then well have been demolished. Instead, Manchester University bought it in 1968, to house the additional students who needed somewhere to sleep, now that higher education was rapidly expanding.

By the early 21st century, Mrs. Gaskell was being rediscovered: That’s when TV dramas were made from North and South (2004), about a young woman witnessing the horrors of Manchester (“Milton”, like “Mill Town”, hint, hint) in the early Industrial Revolution, and Cranford (2007), about the Industrial Revolution arriving in the 19th century countryside.

In Manchester, a charity (nonprofit) bought the house in 2004, and, after restoration, it was opened to the public in 2014.

Well, of course, Hoosen and I had to visit. In fact, Elizabeth Gaskell’s house was top of my list of places in Manchester I wanted to go.

There’s something about a writer who asks all of us to look around honestly at a time of massive change, to do so with care, compassion, and anger, to stop and think.

Clearly, I’m not the only person drawn to Mrs. Gaskell’s work in our times of change and trouble. Although it was a bit discouraging to see that most of the comments on the YouTube clips of North and South amounted to “Oo, isn’t the ruthless factory owner handsome?” I shouldn’t be so naive, but I suspect naivete (or maybe optimism is a better word) keeps me writing, rather than sitting in a bar somewhere, weeping into a strong drink.

Time was an issue for Hoosen and me: We were in Manchester for one day, on a Wednesday, and it turns out, that’s the only day another fascinating Manchester attraction is open each week, so we had to see them both. I'll write about the other in its own post.

I hate being rushed. But I figured out there was a ten minute walk between the two museums, and since the other place opened later, we took a cab to Mrs. Gaskell’s house as soon as its doors opened.

Once the car passed under the motorway overpass, we were no longer in the gritty/hip Manchester I described last time. Gone were the tall stone buildings, grim graffiti, and touristy shops. Instantly, we were in a modest suburbia. Mrs. Gaskell’s grand house now faces suburban row houses. Touch the photos to see.

Let’s be fair: Not for Mrs. Gaskell the apologetic hypocritical drivel I sometimes hear these days from people who live in privilege, when they bemoan the lack of diversity and urban grit in the places they choose to live! Mrs. Gaskell made no apology for wanting herself and her family to be far from the urban misery and squalor she wrote about. Oh, okay, maybe a little bit.

In her day, the house was not even surrounded by little houses as it is now, but adjoined gardens for flowers and veggies, a play space for the kids, and a large field, where the Gaskells kept a cow, for milk, cream, and butter. She called this “A large, cheerful, airy house, quite out of Manchester smoke.”

When the Gaskells moved into this house in 1850, it was a time of huge contrast between airy luxury, how the upper middle-class manufacturers and professionals and their families lived, and cramped squalor, how the vast majority of working people lived. Yes, Elizabeth did feel guilty about this, as a good liberal, thinking it was selfish for the family to occupy such a big place when so many in Manchester were suffering. Of course, she did it anyway, because who wouldn't?

The best she could do, according to the museum guidebook, was make the place a welcoming home for her visitors, who tended to be other middle-class people who set out to do good. Among them were her dear friend Charlotte Bronte, her editor, Charles Dickens, and her American fellow abolitionist, Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and yes, she came here, all the way from America).

Fun Fact:

If you were a posh person who stopped by another posh person’s house, and weren’t necessarily expected, you brought a visiting card, like a business card but with your name only, and gave it to the maid, so she could check if the bosses wanted to see you.

Those visitors who came through the doors of 84, Plymouth Grove in the early 1860s probably brought visiting cards in the cool new style: With photos as well as names. Charles Dickens certainly did: His card showed him writing at a desk. Mrs. Gaskell’s own card photo featured her wearing one of her favorite Paisley shawls, while pretending to read a book.

The hospitality continues at 84, Plymouth Grove.

The crack team of volunteers at Elizabeth Gaskell’s house are pretty much perfect. Friendly, knowledgeable, relaxed, and welcoming, they are a joy. So between them and the great little guide book, I came away knowing far, far more about Elizabeth Gaskell, or at least, how she lived at home. And 84, Plymouth Grove, Manchester, does, very much, feel like home. On purpose.

We visitors were invited to touch everything we saw, sit on chairs, and make ourselves at home. Items belonging to the Gaskells are staged to look part of the room, but cleverly enclosed in glass, where we can’t get at them. Everything else is reproductions, and we’re all welcome to put our grubby paws on stuff. I loved the box of Victorian toys in corner of the morning room. A morning room is a living room traditionally used in the morning, where a family might eat breakfast, but the Gaskells used it as a nursery/ room where their kids played. Kids visiting the museum are welcome to play with the Victorian-style toys.

Mrs. Gaskell’s desk sits nearby. See, Mrs. G. didn’t ignore her four daughters*. She worked around them, in the same room. That would take some doing, I thought. Even with a nanny.

*Her only son died five years before the family moved into this house, from scarlet fever, one of the many cruel diseases that ended children’s lives before vaccinations. If you detect a slight bias in my work in favor of vaccinations, you bet your ass there is. Any historian even vaguely familiar with the ghastly state of public health in 19th and early 20th century cities, and especially with infant mortality, thinks vaccinations are a good thing, because, duh.

Mind you, Mrs. Gaskell had five servants: A cook to make all the meals and snacks, two housemaids to do all the cleaning, a waiter (to serve at table, but surely he had more to do than that?) a gardener, and a ladies’ maid, Ann Hearn. The ladies’ maid doubled as a nanny and traveling companion, giving Mrs. G more freedom to travel without her husband than women of her class normally got.

On display in the house is Elizabeth Gaskell’s passport, the earliest example I have ever seen of that now-common document. It’s just a handwritten letter, and it’s not only for Mrs. G., but for her four daughters, and even her maidservant. Think of it as a very fancy letter of introduction, and one that together with her being British in the age of Empire, and dressed in fine clothes, gave her the freedom to travel abroad.

The house itself invited in the outside world. It was filled with books, and the sound of music from the piano and singing by the family . . .

Oh, hey, I haven’t told you about Mr. Gaskell! I had never thought about him before. Maybe he was a cotton manufacturer, like the love interest in North and South? Nope. He was a Unitarian minister. That did surprise me.

Unitarianism, minority religion that it is, is relatively big in America, while hardly known in England these days. Unitarians began as Christians who didn’t believe in the Holy Trinity, that is, they didn’t think Christ was God Incarnate. They also thought that people should believe what they like, based on their own reason, which explains why most no longer identify as Christian.

When I first came to the States, back in the early 80s, I lived for a year with a Unitarian family. I was quite alarmed when I first learned that I would, since I had confused Unitarians with Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s somewhat loopy Unification Church, a cult that was popular in those days. Fortunately, I soon learned that the Unitarians were a harmless lot, who met on Sundays to hear secular sermons on social justice, and hang out with each other. Many beards were in evidence. I tend to prefer my religion to have more religion in it, or else I can’t see the point of dragging my butt out of bed on a Sunday. But the many Unitarians I met were either nice, interesting, or both.

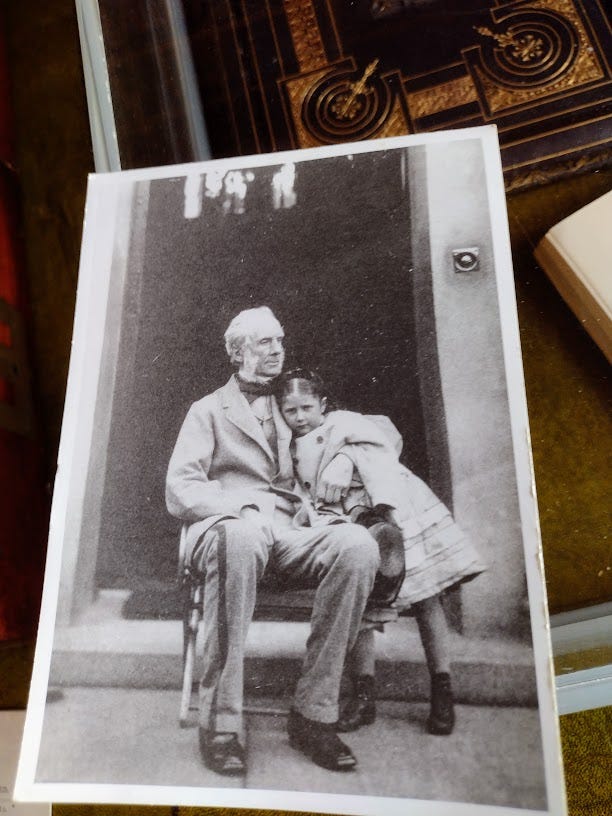

Rev. William Gaskell was popular enough that he served fifty years in the same Unitarian chapel (church). A soiree (evening church gathering) was held to mark that anniversary. The volunteer in what had been Rev. Gaskell's study also directed our attention to a lovely photo, of an elderly Rev. Gaskell with a little girl who was the granddaughter of two couples from wealthy manufacturing families who were also devoted Unitarians.

You may have heard of the kid: Beatrix Potter. When Rev. Gaskell died in 1884, she wrote (according to a Gaskell House blog), “Dear old man, he has had a very peaceful end. If ever any one led a blameless peaceful life, it was he.” By the way, “OMG, all these people knew each other" is turning into a major theme of this trip.

I now felt warm feelings toward William Gaskell. This house did make sense of a Victorian man who didn’t seem bothered that his wife was a famous novelist. Her novels, which were mostly critiques of the state of society, also now made sense. And Elizabeth Gaskell wrote most of those books right here, in this house.

It’s been a very long time since I read Mrs. Gaskell’s work, so I returned to it shortly before I left the States last month. While I’m fascinated by North and South so far, I’m also frustrated by it. Mrs. G. seemed to be pulling her punches in creating the character of factory owner/enthusiastic capitalist Mr. Thornton, who I now realize as I write (holy cow!) had a huge subconscious impact on my own character of Mr. Thornhill in A Different Day, an English lawyer in the American South in 1851, who was up to his armpits in slavery. Good Lord.

Anyhow (cough), back to Mrs. Gaskell. I said something about her soft treatment of Mr. Thornton to one of the museum volunteers, Philip, a delightful retired English teacher who told us all about the drawing room, the main living room. Philip and I quickly bonded over a shared love of Coronation Street, the extraordinary Manchester-based and Manchester-produced soap, although he was a bit shocked that I haven’t watched it much since I emigrated (hey, it never caught on in America). He explained that when Mrs. Gaskell wrote Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life in 1848, two years before she moved to this house, she took the perspective of working-class people, and let the rich manufacturers (and Manchester’s masters) have it with both barrels.