The Free Love Commune That Sold Out (1)

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Meet romantic Christian socialists who traded the promise of heaven on earth for silver. Or did they?

How Long Is This Post? 4,900 words, or about 25 minutes.

This is an Annette on the Road post at Non-Boring History, from my travels, reflecting my role as historian as tourist!

A Mansion in the New York Countryside

“I didn’t even know it was here.” “I never knew what it was.” I heard that sort of thing several times from the locals who work at, or near, this Victorian mansion. And those who got curious were completely fascinated to discover what the mansion was all about. The housekeeper told me she was learning everything she could about it. “I hated history in high school,” she said apologetically to me, “I’m sorry.” I tried to tell her that there was no need to apologize at all, but I don’t think it registered with her that a historian could sympathize with her about high school history. “But this place is really interesting,” she said.

The mansion is in a rural area that’s been devastated by a factory closure. People lost jobs. Pensions. Healthcare insurance. It’s a complicated story involving outsourcing, foreign competition, purchase by a private equity company that picked over the remains, and corporate greed. The bottom line, though, is that 1,100 jobs that actually gave people a decent living are gone, and haven't been replaced.

The bitterness with which one local spoke to me of the impact of the factory closure, not to mention the worn look of much of the area, like small towns across America, was my tip-off that all is not well in a region in which Americans once dreamed of utopias, perfect societies.

But now, let’s talk about a culty commune!

Heaven on Earth

The charismatic leader emerged at a time of great turmoil* in America. He offered an exciting message: Perfect people were possible, and he knew that, he said, because he was one of them. Mr. Perfect quickly began to attract followers for his dream of heaven on earth. They started a commune, living together and holding property in common.

*Honestly, I’m hard pressed to think of a time without great turmoil in American history. I think 1976-1978 might be our best bet, but those years were in Jimmy Carter’s presidency, followed by his landslide loss to Ronald Reagan, so what do I know?

The Leader arrived at a time when Americans were deeply divided into hostile camps. A time when a new economy was starting to enrich a few. But it was also making many middle-class people feel irrelevant. Modern life increasingly dictated that you were either fabulously rich and successful, or a poor and miserable loser. There was no middle in this vision.

This was also a time when middle-class people were thinking very differently about sex (as in naughty activities) and gender (gender meaning what it did until five minutes ago, the roles assigned to the two biological sexes to which practically everyone belongs) than they had in the past. Middle-class women were expected to give birth to lots of kids and stay home with them, withdrawing from the world, while men went out to graft (or grift) as hard as they could in pursuit of a big house filled with goodies.

And then a tidal wave of religious enthusiasm swept the US, offering relief: A chance to escape this earthly torment, since Mars was not yet an option, by either awaiting the arrival of the Messiah (expected soon!), or, in some cases, not waiting, and setting about building perfection here on earth.

This was the complicated and troubled America in which the Leader unveiled his unique ideas. He proposed “complex” marriage. This involved equality of men and women, sex with multiple partners, practice of birth control by men, communal raising of kids, and a simple life of joyful work, with every commune (or “family”) member choosing what they wanted to do. Everyone was aiming for spiritual perfection. They would live in a beautiful, even luxurious setting. Education, the arts, and life would be lived together as a family in a huge Victorian mansion. The mansion above, in fact.

I lost you, didn't I? You're still back there with furrowed brow, wondering when on earth I'm talking about. Hold on. Let’s chat.

I mean, this story could be set in the 1980s, with the rise of Wall Street, a focus on the individual, and massive job losses in the Rust Belt. . . . This was also the time of yet another religious revival, with TV preachers like Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker preaching prosperity gospel, which promised health, happiness, and most of all wealth to anyone if they would only believe. That belief in prosperity gospel is still very popular by the way, although Jim Bakker changed his mind about all that in prison: He’s now back on TV, only selling survival rations in tubs for the coming apocalypse. Or maybe you recall the 80s commune in Oregon, led by Bhagwan Shree Rashneesh, with his fleet of golden Rolls Royces?

Or am I talking the 1960s, when Americans were also deeply divided, and when some started communes to reject mainstream life after World War II, with its focus on large suburban families, women as homemakers, and men as breadwinners who competed for material wealth? Or maybe today is about the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

Don't give up on me. I'll let you into my little deception.

I'm not talking about the 20th century at all. I'm talking about the 19th century.

The Oneida Mansion in Oneida, New York, was built during the Gilded Age. For my British readers (or my American readers who struggle to remember anything from the textbook and worksheets distributed by Coach Grunt in high school), let’s recap what that was.

The Gilded Age is the name we call 1870-1900 in the United States, and it comes from Mark Twain’s 1873 novel, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. This was an era of stupendous wealth, but also of great poverty: Beneath the thin and flashy golden layer (gilding) lay much suffering and discontent. Massive economic growth that had begun before the Civil War accelerated during and after it, and created amazing wealth in factories, mines, finance, and railroads, as the American Industrial Revolution came into full swing. (BTW, Britain was the first industrial nation).

Immigrants from Europe, pushed by poverty and discrimination, came to the US to work in factories, and lived in slums and on low wages. A tiny (and I do mean tiny) handful of Americans, many newly wealthy, built huge houses, and presided over it all. They were the gilt of the gilded age.

So this enormous house (above) is typical for its time. Except that it was built by and for a Christian socialist commune.

Maybe you remember the Oneida Community, Americans, from the ten seconds you heard about it in high school? It was one of several utopian movements, aiming for a perfect society, that arose (or gained followers) in the 1840s, in the aftermath of the Second Great Awakening, the religious revival that swept America. I taught—briefly— about the Oneida Community in my US history survey class at Georgia Southern University. I didn’t say much about it, because I didn't know much. I'm an early American historian. Now I wish I had known more.

The Oneida Community in upstate New York broke every Victorian rule. Victorian culture promoted individual pursuit of material success. It encouraged families to create—or aim for— comfortable middle-class homes cluttered with possessions. Women, in big impractical skirts, were to be concerned with home and kids. Men were in charge. These were the ideals.

By being none of the above, the Oneidas, never more than 300 people, show us what mainstream Victorian culture was. They, like other 19th century Utopian movements (including the Shakers and the Mormons) help show us that at least a few people aimed for alternative ways of being.

But, in the end, like so many utopian movements, trying to create a perfect society on earth, the Oneidas threw in the towel. Even then, they quit differently than we might have expected, as we’ll see. It’s complicated. It’s fascinating. It’s going to need more than one post.

The Oneida Community started as a slightly culty commune. I say “slightly”, because there was a revered leader, but nobody was forced to stay. The community's practices cause uneasiness, even in the supposed “anything goes” early 2020s, when, in fact, rather like the Victorians, we’re terrified to discuss anything at all. Especially sex (she says mysteriously).

We live in strange times, just like the Oneidas. But because history never repeats itself, despite that cliche about those who don’t learn from history being doomed to repeat it, we don't even grasp the actual lessons of studying it. The greatest lesson of history, according to Annette, anyway, is not learning specific tactics for avoiding the same problems, but knowing that, if you wait, those problems, like everything else, will end eventually, even if only in a massive pile of corpses (historians always hope it won’t come to that).

Look, historians tend to hide during periods of change when things get scary. We don’t have all the answers to the riddle of human existence. Most of us don’t even like talking to the public. You want quick answers to big questions, and we don’t have those.

You know who did have all the answers to life's big questions? John Humphrey Noyes, that’s who. And that's why he was able to gather enough people to start the most unlikely of all Victorian communes.

The Mansion

“What did you say this place is?” Hoosen asked. Even arriving after dark, we could see how big the Mansion was.

“A Victorian Christian socialist free love commune,” I said. Being my long-suffering spouse, Hoosen took this in his stride. I rang the bell, and a gangly kid named Zach, in a tie-dye shirt, showed us to our room.

Before I forget? The Oneida Mansion is now a museum. That's right. Night at the Museum was about to become a stay in a historic commune. We were renting a room in the Oneida Mansion, a huge complex that once housed up to 300 people in spacious comfort. The museum sections of the building were locked after hours, of course, but we were welcome in the large modern library, and the vast common room, which was added much later, in 1914. It was quite a treat. Hoosen entertained himself playing lord of the manor in the library, before both of us explored the museum the next day. I’m no expert. Much of what I am about to tell you, I learned from the museum. But it’s a start I want to share, because, wow. Utopian communities in America go back to the Puritans, and this one’s a doozy.

The Man Himself

Oneida Community founder John Humphrey Noyes was not what you might call classically good looking. But he made up for that with bags of charisma.

Noyes and his associates offered people a chance to escape Victorian conformity. The Community's men and women, and soon, children, would be free to live a life in which possessions didn’t matter, but learning did. Family members (as they called themselves) were to love each other. If a community member became a mother, but wasn’t all that fond of child-rearing, that was fine: All the children were raised together by the family. You chose the work you preferred to do, for the most part. A woman who liked accounting? Accountancy in Victorian Britain and America was for men. But at the Mansion? No problem. A woman could be a bookkeeper in the Oneida Community.

And Oneida women wore trousers, long before Katharine Hepburn! They cut their hair decades before short hair went mainstream! Those radical Oneidas believed women were men’s equals. How equal? In the large balconied hall where the Community met, dined, listened to sermons, lectures, and music, and celebrated, hangs a gallery of leaders’ portraits.

There are two men, one of them John Humphrey Noyes, and two women. I was suddenly reminded what a thrill it was to dine at Newnham College, a women’s college at Cambridge University, surrounded by portraits of distinguished Victorian women, not just the usual blokes in beards. Oh, and the Oneida Community started in 1848, the same year as the first women’s rights convention at nearby Seneca Falls.

Life at the Mansion included lots of work, but work was often done as a social activity, in what were called “bees”.

And it wasn’t all chores: Community members were always coming up with new ideas for items to produce and sell. Life wasn’t all work, either. There was entertainment. Art. Games. Classes. Music. Lots of social activities. Lectures, sermons, and spiritual development. A full library, which was well-used, as you see in the drawing below:

The Oneida Mansion was designed to encourage everyone to be social, to elevate each other spiritually toward perfection. That’s why a family member’s room looked like a monastery cell. As a 19th century Oneida Community member, you got your own room with a very narrow twin bed, a desk suited to letter-writing, but not research (that’s what the library was for), a washbasin, a chest of drawers, and your very own pot to poop in. Nah, I’m being flippant. Seriously, all Victorians had chamberpots, but not all Victorians had baths, heating, and the kinds of modern comforts the Oneida community enjoyed.

The whole point was that you spent as little time in your room as possible, and that you instead relaxed and built spiritual relationships with everyone else in the communal living areas, which were much more inviting. You were not expected to talk all the time: I’m sure there was plenty of companionable and contemplative silence. Here’s one of the original common rooms. You can see doors to members’ rooms around the ground floor and the balcony:

And at a time when a growing (but still tiny) class of the super-rich were starting to build mansions best described as over the top, and many Americans lived in tenements and shacks, people who were accepted to the Oneida Community could live in airy spaces with high ceilings, good food, good company, plenty to do, and lots of room to live and breathe.

Ready to move in? You can tell I found it rather tempting. Reading? Gardening? Room to grow? Maybe a job making cakes for everyone? Sounds lovely.

But the more I learned, the more complicated the Oneida Community turned out to be. It’s a great example of how hard it can be to assign naughty and nice labels in history. “It’s complicated”, the historians’ motto, absolutely applies to the Oneida Community.

Sex! Now I have your attention . . .

John Humphrey Noyes was keen for the world to know that his “complex marriage” did not mean free love in the way most of us understand it. This was very Victorian hanky panky. Everyone loved each other, at least in theory, but not everyone got to have sex with each other. There were no orgies. Instead, there were rules, interviews, and, I think, committee meetings. Both parties had to consent, and the only couplings we know about were conventional in one way: They were heterosexual.

Noyes had very definite views on birth control. He believed that women should not have children they didn’t want, and that they needed an alternative to abortions. Abortion was legal in North America until the mid-19th century: Even the strictest laws in the British colonies said abortion was permitted until “quickening”, when the baby could be felt moving in the womb, at about 16-20 weeks. After 1860, laws against abortion were tightened. But women continued to obtain them (or do them themselves) anyway, as they had through human history.

In his 1872 pamphlet on birth control, Male Continence, Noyes quoted a letter that a woman in the Community had received from a friend elsewhere. The word “operation” refers to abortion:

I must tell you a sad story. Two years ago last September my daughter was married; the next June she had a son born; the next year in July she had a daughter born; and if nothing happens to prevent she will be confined for the third time in the coming June; that is three times in less than two years. Her children are sickly, and she is sick and discouraged. When she first found she was in the family way this last time, she acted like a crazy person ; went to her family physician, and talked with him about having an operation performed. He encouraged her in it, and performed it before she left the office, but without success. She was in such distress that she thought she could not live to get home. I was frightened at her looks, and soon learned what she had done. I tried to reason with her, but found her reason had left her on that subject. She said she never would have this child if it cost her life to get rid of it. After a week she went to the doctor again. He did not accomplish his purpose, but told her to come again in three months. She went at the time appointed in spite of my tears and entreaties. I told her that I should pray that Christ would discourage her; and sure enough she had not courage to try the operation, and came home, but cannot be reconciled to her condition. She does not appear like the same person she was three years ago, and is looking forward with sorrow instead of joy to the birth of her child. I often think if the young women of the Community could have a realizing sense of the miseries of married life as it is in the world, they would ever be thankful for their home.

And it gets more interesting. Noyes believed in birth control. And get this: He believed that birth control should be the responsibility of men. And that’s where his ideas, well, start to get a bit, well, out there.

I’m a bit Victorian, honestly. So there will now follow a quick discussion of sex that may be slightly embarrassing to you, and certainly is to me, but also pretty fascinating. Noyes believed in what he called “male continence”. But he didn’t mean withdrawal. Oh, no. He meant that men should not ejaculate at all unless he and the woman agreed to conceive. And he didn’t approve of masturbation, so . . Um. Yes. Well. Ahem. But the sexual complication doesn’t end there. Oh, nooo. We’re just getting started.

Community members needed permission to have sex. And it was just sex: They didn’t “sleep together”. Couples’ romantic attachments were frowned upon, and they were expected to return to their own rooms once the deed was done.

They also needed permission to have babies. Only certain members of the community, those judged spiritually and physically superior, were given permission. They developed a program of eugenics (selective breeding of people) that they called stirpiculture, and the resulting children were known as stirpicults, which sounds straight out of science fiction.

If this is ringing alarm bells, it should. This is not quite the eugenics of the Nazis. But it was definitely headed in that direction. And let’s be clear: Eugenics developed in the United States, not Germany, and led to all sorts of horrors (including the deliberate sterilization of people of color) that I simply don’t have time to describe today. Only when it reached its fake-science zenith was eugenics exported to Europe, where Hitler, Joseph Mengele, and other Nazis took it to its hideous conclusion: The horrific experiments on children. The deliberate murders of millions.

But—here’s the thing— I don’t think this outcome is at all what Noyes or the others in the Oneida Community had in mind. And that’s what’s so scary about it. The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

This is where cultural historians like me take a deep breath before talking to the public. Look, all of us modern people tend to assume the world didn’t really begin until we were on the scene. Or at least that people were getting things wrong until we showed up. The historian’s job is to dig into the past, to confront the past as a foreign country—which it is—and seek to explain it on its own terms, not get out our wokey hammers and smash it, because honestly? That’s not helpful in understanding what was going on.

You will not be shocked to know that the Oneida Community believed that men in the community judged most spiritually advanced —its leaders—were those most likely to have been given permission to conceive. You will also not be shocked to know that John Humphrey Noyes was among them. In the end, there were 58 children at Oneida, and Noyes fathered nine of them. The children were raised together by the community, and parents were discouraged from attaching specifically to their children, which was clearly a struggle for some, and not just mothers.

But you may be shocked by this next bit. As the children of the community grew, teenagers were assigned “mentors” to initiate them into sex, and that sex with more spiritually advanced elders was believed to impart that spirituality to the younger partner: Women over forty, less likely to get pregnant, had sex with teenage boys. Older men (steel yourself), including John Humphrey Noyes, initiated sex with young virgins, and there’s evidence to suggest that Noyes reserved the 12 and 13 year olds for himself.

I know, right? Not a surprise to 21st century people. But here comes the thinking that historians are trained to do, and that’s to look at the historical context of behaviors we may find repellent today (or may not, giving the truly appalling statistics on child sex trafficking). Oddly enough, older men taking much younger partners was one of the few ways in which the Oneidas did not clash with mid-Victorian values.

Today, the age of consent for sex in many US states is not always 18 as most Americans assume, but sometimes 16 or 17 (and often younger in cases where both partners are closer in age). It’s a confusing situation. I actually found conflicting information for the states I looked up. And ages 17 and 18 are high when compared with other countries. In the UK, the age of consent is 16, as it has been since 1885, when it was raised from 13.

Note that British date for a raise in the (heterosexual) age of consent: Things were changing, and that was also true in America. For much of the 19th century, the age of consent in the US was between 10 and 12. That started to change in the late 19th century, and by the 1920s most states had raised the age to 16 and up—even so, to repeat, there is still much confusion, as I found when I tried to look all this up.

The point here is not to argue what the age of consent should be, or should have been, but to make the point that when the Oneida Community was formed, this part of what they were doing wasn’t illegal, and wasn’t even considered immoral. By the time the Community ended, however, it was both. Ideas and values change over time, and not all in one direction. I’m willing to bet that when, in 1963, Paul McCartney wrote the words “She was just 17, you know what I mean”, he never expected this would lead to awkward exchanges with American interviewers. And John Humphrey Noyes didn’t expect when he first started his commune that the authorities would try to arrest him for statutory rape. But that’s exactly what they tried to do in 1879. Noyes escaped by making a run for the border, and he died in Canada a few years later, having told his followers by letter that he no longer thought complex marriage was such a great idea.

But by then, the Community’s fate was no longer in Noyes’s hands. Soon, it would be in the hand of its children, children who had fond memories of the community they grew up in. And that’s where things become—surprise!—even more interesting. And why I need a Part 2 to this story. And even then, we’re barely scratching the surface.

The Oneida Community’s Legacy is About To Get More Complicated

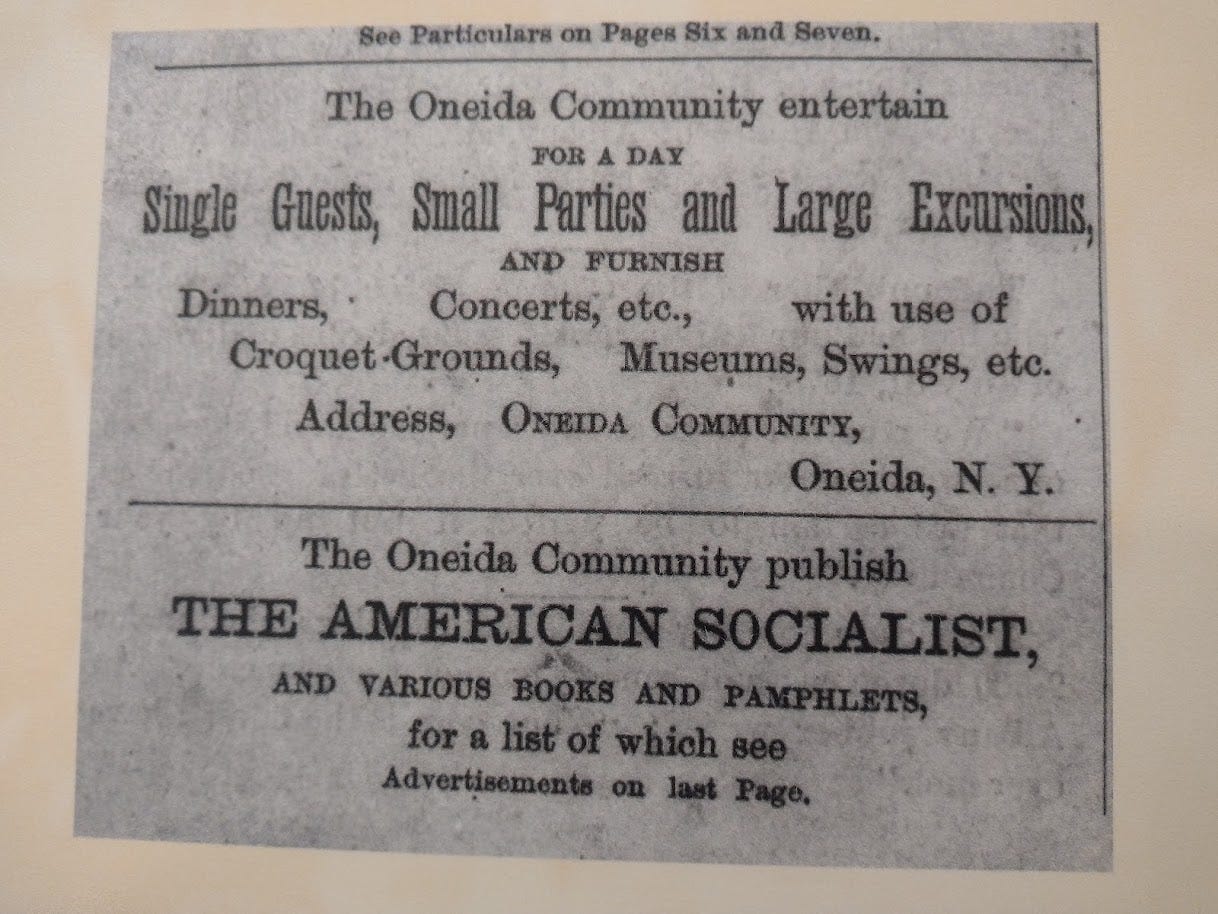

In the 1870s, every summer, shocked and horrified respectable Victorian New Yorkers flocked in their thousands by train to Oneida to make absolutely sure they were shocked and horrified by the Oneida Community. The family did not hide from their curiosity, not least because they always needed income. They invited the visitors with ads, and met (and charmed) the curious with their hospitality. They laid on entertainments, and served bountiful meals for nominal fees. The Community worried that the 75 cents they charged per person in 1872 for a lavish repast of homegrown and homecooked food was too expensive for their guests: They lowered the price to sixty cents, and even offered a cheaper alternative “plain” meal, because the Community worried that the full dinner experience was too pricy for some visitors.

The story of the Oneida Community is not just the story of one man. It is not an uncomplicated story. And it would be lazy and misleading to wield it as a political weapon in the 21st century, whether from right or left. The Oneidas, even as they rebelled against the Victorian age in which they lived, were very much a part of it, as we shall see. What happened to the Community after their leader’s hasty departure is another astonishing story I will relate soon at Non-Boring History. Because there is so much more to this community than who slept with whom. If you are currently a free reader, please join us for the cost of less than a cup of coffee a month for everything I write. You’ll even get a free trial period, and a fascinating bonus story below!