Reading the Abbey

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD English abbeys start to look alike . . . Until we look closer, and read a bit

Note from Annette

Join us as a Non-Boring History member today for full access to one of the few newsletters that is:

Written by a proper qualified historian (who thus feels comfortable being silly, because she doesn’t have to pompously pretend she’s something she’s not)

Actually about history, not current politics (Look, there are plenty of people writing about the US presidential race, mostly in uninformed ways, and all without the gift of clairvoyance, i.e. seeing into the future, while preaching to people who already agree with them. I refuse to participate on principle, which is why I’m not rich.)

Aims to show you why historical knowledge and thinking inform and enliven life, from someone who walks the walk, as a historian with a PhD (early America and modern Britain), publications, and experience in both doing and teaching academic and public history (phew!)

Join us!

Today, we look at a big church in small ways . . .

Watch Out for Flying Buttresses!

Ooh, I said to Hoosen, as we approached Tewkesbury Abbey (yes, in England), isn’t that a flying buttress?

Hoosen, who is, to remind you, an engineer by profession, was happy to confirm that I was correct! I was thrilled with myself. I don’t think I’ve thought of flying buttresses since I first learned of them, long ago in the mists of time, probably as an elementary schoolchild in England in the late Middle Ages.

So, the idiot’s (i.e. my) version of how flying buttresses work: To prevent the walls of a very large stone church from bulging out and collapsing, they would have to be very, very thick. This would be a problem for adding windows, and especially lovely stained-glass windows that were the audiovisual aids of churches in the Middle Ages. So flying buttresses add support that allows for thinner stone walls, and thus lovely stained glass windows.

Flying buttresses were purportedly first used in Europe at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris in 1180. They are rare in England. Yet here they are at Tewkesbury Abbey, which was built between 1087-1121. Okay, I have my suspicion that the flying buttress on the right is a Victorian addition (you would be amazed how much vandalism the Victorians did to churches and castles and whatnot in the name of “restoration”: If a medieval building looks too good to be true, it probably is).

But the flying buttress on the left seems to be the real deal, completed no later than 1121. So there, France! Oh, wait. Tewkesbury Abbey was built starting only 21 years after the Norman Conquest, when England was invaded and taken over by the Normans who were basically, um, French.

Anyhow. Let’s just be impressed by medieval engineering, and stop thinking of medieval people as “ignorant” and “dead people from Back Then.”

Unless we think we could have come up with the flying buttress, or understood the need for it? I bloody couldn’t. Annette’s Abbey would have collapsed long ago in a cloud of dust.

I’m ‘Enery the Eighth, I Am. ‘Enery the Eighth I Am.

So the name Tewkesbury Abbey suggests a monastery is attached, right? Well, there was, once.

But then King Henry VIII, keen Catholic that he was, nonetheless decided to divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon. That’s because she had only delivered a daughter, Mary, and not a son. And only boys made good monarchs, right?

Boy, (no pun intended) Henry would have been surprised by how well Elizabeth I, his second daughter (by his first trophy wife, Anne Boleyn) would do as England’s ruler!

But Henry couldn’t have known that, of course, because Elizabeth wouldn't (and couldn't) be Queen until he was dead. No, his immediate challenge was to ditch his wife, and marry his girlfriend, who would surely deliver a boy (she didn’t) to continue his family dynasty.

Henry’s need for a strapping son to project strength was especially urgent because his family’s dynasty was very new: It had been founded by King Henry’s dad, Henry Tudor, in 1485. The Battle of Bosworth of that year pretty much ended the dragged-out civil war known as the Wars of the Roses, in which the northern warlords of York (logo: white rose) and Lancaster (logo: red rose) had fought for control of all England.

So the first Henry Tudor (dad of Henry VIII) was a member of the House of Lancaster with a very vague possible claim to the English throne. Vague claim or not, he got to be king after he defeated King Richard II at Bosworth Field. Because of Bosworth, 1485 marks the start of modern English history, just as, seven years later, Columbus sailing his three ships starts the arrival of modern history in America.

“Modern” isn’t a value judgment, before you grab your wokey hammer and start hitting me with it.

But whatevs, I’m going down a rabbit hole . . . I’ll keep this short . . .

Anyhow, as I said, Henry Tudor (the original) pretty much ended the Wars of the Roses when he became King Henry VII. He wrested control from the warlords (aka aristocracy) by handing power to the gentry, their lesser, also landowning, and locally important cousins, giving them local government jobs which made them feel important, tied them to London, and most of all, tied their futures to the success of Henry VII’s reign.

So back to Henry’s son (Mr. Divorce). He could not get the Pope to agree to allow him to ditch Catherine and remarry, so he announced that he himself would be the pope in England, going forward. He then granted himself a divorce, and married his girlfriend (Anne Boleyn). After that, Henry VIII started to see added benefits to being in charge of the Church in England: He announced that nobody really needed monasteries or monks (debatable, since monasteries served as employers of many, and also acted as hotels, schools, and hospitals). Henry VIII thus abolished (aka dissolved)the monasteries, confiscated their money and valuables, and gave their lands and properties to his supporters among the gentry and aristocracy, some of whom adapted monastery buildings into houses—castles no longer being needed since the Wars of the Roses ended.

Tewkesbury Abbey was one of the larger monasteries. With the dissolution of the monasteries (as it's called), the last Abbot was now pensioned off, and later given a government job. The other monks were just told to go away.

Naturally, Henry confiscated all the valuable stuff, silver, gold, etc. The monastery buildings fell into ruin, their stones pinched to build other buildings in the growing town of Tewkesbury. And the Abbey church? The townspeople bought it off Henry VIII for £483, somewhere (maybe?) around £200,000 today, to serve as their very, very large parish church, since otherwise they would have to have built a new one, which made no sense when they had one that they had been using for centuries, even if it was too big. And that was probably a good deal.

Abbey Seeing You (In All Those Old Unfamiliar Places)

I enjoy being a tourist, and I also enjoy watching tourists. I’ve had many opportunities to do both, let’s put it that way. And I have noticed that the vast majority of visitors to castles, abbeys, cathedrals, palaces, and massive old houses glance around vaguely as they walk through, unseeing, comment to their companions on occasional bright/shiny/gory/peculiar objects, barely pause to maybe read a label or two, and then gratefully retreat to the gift shop and the tea room/cafe (probably in that order).

I flatter myself that I do the same itinerary only better, much more slowly, with more reading and asking questions, and in the spirit of trying to understand at least a little of what I’m looking at. Mind you, some churches do a better job than others of explaining themselves to visitors who come for the history.

Canterbury Cathedral, beautiful though it is, is rubbish at informing visitors (bad labels, lousy guidebook), as is Westminster Abbey, and they charge a lot to get in. This is why I strongly recommend dropping “bucket lists” in the bin. Instead of going to the most famous churches, visit Tewkesbury Abbey. It’s gorgeous, does a very good job for tourists, and asks only for a truly voluntary donation of five pounds per person, which keeps the Abbey maintained for about two minutes. So please do donate!

I had never been to Tewkesbury before. It is in the Midlands of England, up against (but not in) the popular touristy Cotswolds area. Be warned, too, that I’ve only once taken a class in medieval English history, and it was awful. So my knowledge of the Abbey was nil, and yet that’s a situation that has its attractions. More to discover! To inspire reading, perhaps! And thanks to those who are staff and volunteers, this visit did not disappoint.

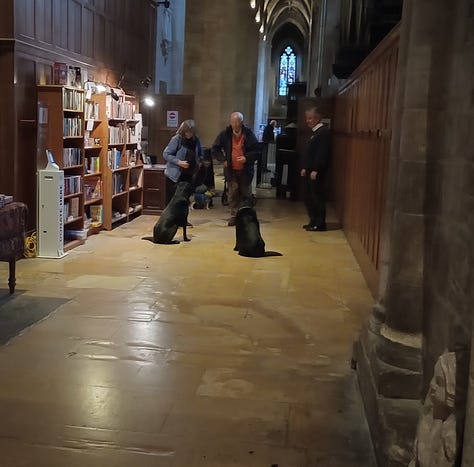

As it happens, not all the staff are human. Let’s meet Eric and Flo. Check out their official credentials around their necks. Their boss and dad is the Abbey verger, the man in charge of the building maintenance, which is why he’s chatting with a crane operator in the first photo.

Writing on the Wall

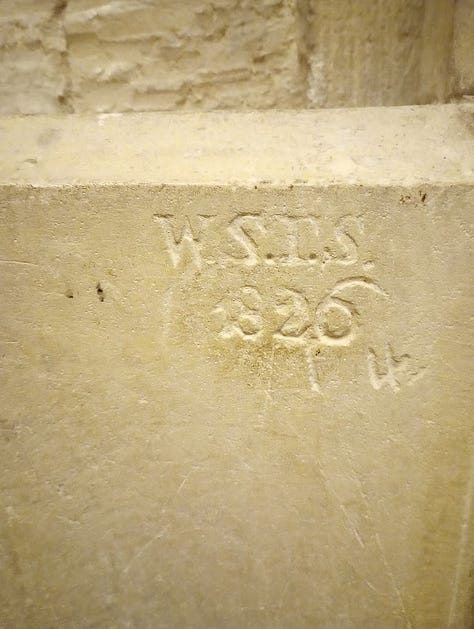

I love historical graffiti (it’s the new stuff, especially done with spray cans, I can’t stand.) So I was surprised and a little disappointed to find the walls and pillars of Tewkesbury Abbey almost entirely free of this entertaining form of vandalism. Indeed, I only found one example, done by some naughty person who went by his initials, WSIS, which he carved into the Abbey wall in 1826. I wondered if the proliferation of graffiti at Canterbury Cathedral had anything to do with it being a place of pilgrimage, where loads of people stopped by to pay their respects to Saint Thomas Becket (as the high point of an otherwise jolly medieval holiday)? Maybe. Don’t know. But people who have come to Tewkesbury Abbey have been very well behaved.

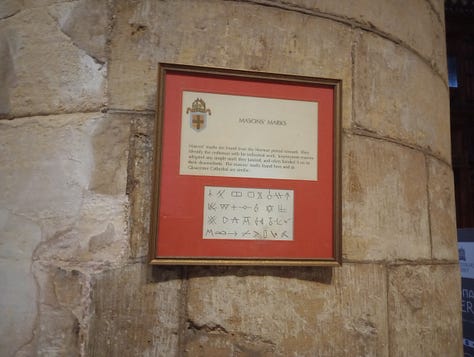

A helpful info panel explains the masons’ marks (below) left by the stonemasons who built the Abbey, which otherwise might just look like scratches. These illiterate men just made up a “signature” in a pattern they liked, and one that was often inherited by their sons/apprentices. I liked the one that looks like a hashtag. Imagine: #JohnTheMasonQualityWorkReasonableRates

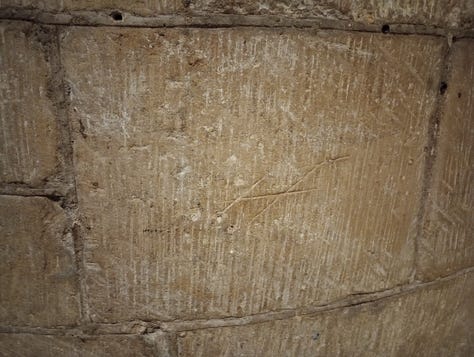

The symbol at top left below is not a mason’s mark. It’s a Christian cross, carved at the doorway to mark the occasion of consecration, which is when the newly built Abbey properly became a holy place. The honors were done by the Bishop of Worcester and a team of lesser bishops, in 1121. Nine hundred years old. Hoosen and I agree: That. Is. Awesome.

A Quiet Corner

An estimated 105,000 people died in the Wars of the Roses, at a time when even a scratch in battle could lead to infection and death. The last true battle of this messy civil war (it’s complicated) was at Tewkesbury in 1471.Like Elvis, the Wars of the Roses had lots of comebacks.

So it’s not a surprise, then, that among the Abbey’s many memorials, to abbots, to local bigwigs, also included those to the rich important dead* of the Wars of the Roses era and earlier, including members of the Despenser family.

Oh, those complicated Despensers, who often ended up executed. Today is not the day to explain them all. So let’s just look at some of the very cool tombs in the Abbey, including those of a Despenser or two.

*Poor unimportant dead people were chucked into mass graves, I assume. Either way, they aren’t in the Abbey.

The Mystery Knight

Changing Places

This tomb once contained a few of the remains of Hugh Le Despenser, Jr., whom the info panel calls “the great favourite” (aka probable boyfriend) of King Edward II.

Hugh had made powerful enemies, so in 1326, after Edward was deposed (and possibly killed), Hugh got the full treatment for treason. This was known as hanging, drawing (being dragged on a little sled to the execution place) and quartering (being cut into bits) which also included having his guts pulled out while he was still alive, and burned in front of him. He may also have had his willy cut off (because of his homosexuality) but the jury’s still out on that.

Sorry to ruin your dinner. Anyway, what’s left of Hugh (his head and an arm or something) was buried in this tomb. In one final indignity, Hugh Jr. was later evicted in the 17th century to make way for the remains of an Abbot who had died in 1347. Life sucks, even after you die.

His Sorrows Drowned

The Duke of Clarence was mentioned by Shakespeare, and not in a nice way, since he described him as “false, fleeting, perjured Clarence”, not exactly a rave review. If Shakespeare was right, Clarence wasn’t popular, because—allegedly— he died by drowning in a wine cask, which doesn’t sound very accidental. He’s buried in a vault under the drainage grating above, along with his poor wife, Isabella, who died in childbirth two years earlier, like many, many women. It’s a bit grim, really, isn’t it?

The Chantry

Before the Protestant Reformation, English people worried about the length of time they would have to spend in purgatory, suffering for their sins, before gaining admission to Heaven. Rich people set aside funds in their wills for a chantry, a chapel staffed by men whose only job was to pray for the soul of the deceased to get out of Purgatory early.

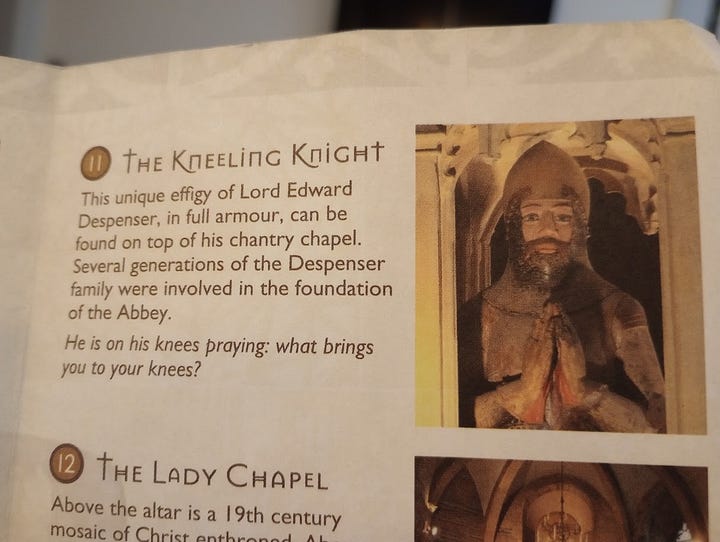

A chantry might be an independent building, but inside Tewkesbury Abbey was prime chantry real estate, with a team of monks in charge of offering prayers, and particularly right next to the altar, so this is where posh knight Edward Despenser’s chantry was built after he died in 1375.

It’s tiny, a sort of chapelette, off to the side of the sanctuary. On top is an effigy of Edward himself, on his knees, gazing at the altar. Inside, a really terrific bit of Medieval painting. This may just be my ignorance, but I’ve never seen a painting of Christ (or maybe it’s God?) holding up Christ on the cross before. Anyway, it’s a very cool chantry.

We Wish to Make a Complaint

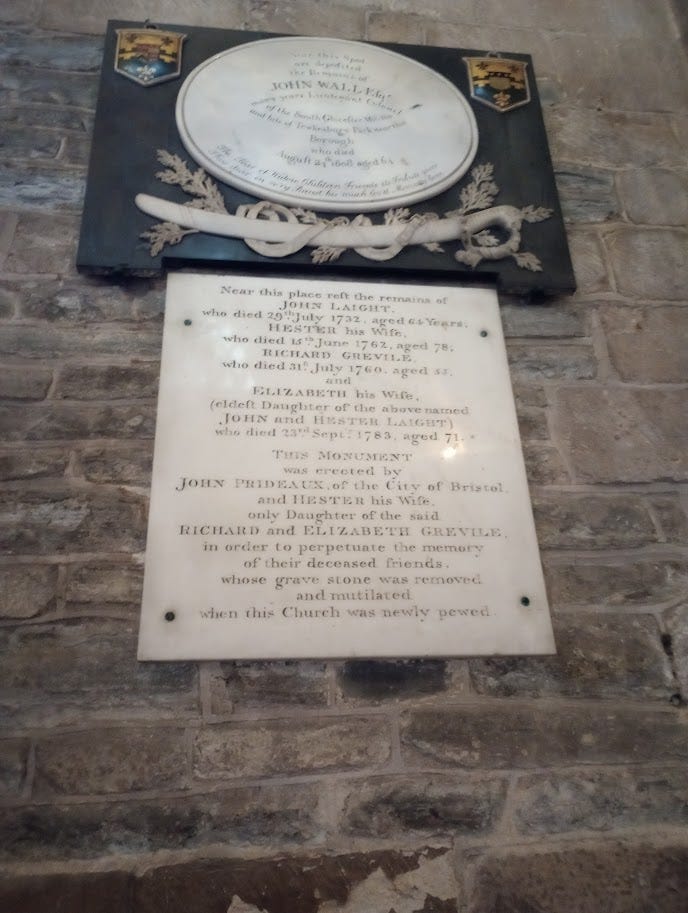

Maybe my favorite monument in Tewkesbury Abbey (above) doesn’t exactly stick out. It’s not for anyone famous or super-rich. But it’s delightful, and I will be happy to explain. Hoosen it was who spotted it and drew it to my attention. Here is the most relevant bit of wording:

THIS MONUMENT was erected by JOHN PRIDEAUX of the City of Bristol, and HESTER his Wife, only Daughter of the said RICHARD and ELIZABETH GREVILE, in order to perpetuate the memory of their deceased friends. whose grave stone was removed and mutilated when this Church was newly pewed.

I shall now translate:

Hello, John Prideaux here. I’m pretty important in the big and important city of Bristol, and my wife Hester and I are extremely upset that you yokels in Tewkesbury did such a number on my in-laws’ gravestone. When you lot put pews in the church, you took out their memorial, without so much as asking us, and broke it. This is why I’ve had to pay all this bloody money to put up this memorial. You’re useless. None of us will be buried here again, you mark my words.

Who’s the Boss?

Take a look at the Abbey ceiling:

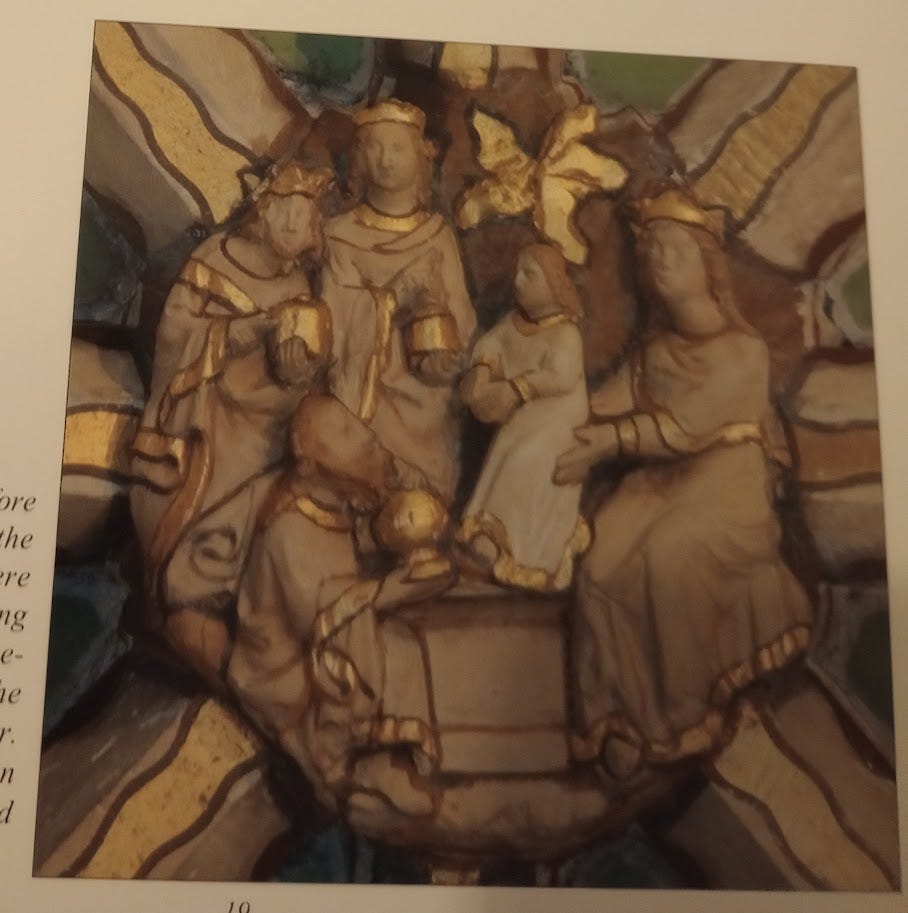

I love bosses. No, not that kind (I have had very few I would work for again, and those ones, I treasure). Boss is the odd name given to small, usually round decorations on a church ceiling. They were added by rich lay (non-clergy) patrons in the late Middle Ages, who liked a bit of decoration in their churches. Richies are also responsible for much stained glass, which is more easily enjoyed.

That's because bosses are very hard to appreciate without binoculars, and that made them a bit of a problem in the Middle Ages, when, I understand, binoculars weren’t really a thing. Luckily, the modern Abbey supplies mirrors to save our necks, and a guidebook to show the bosses up close!

Here’s a closer look from my camera:

Here’s where buying a well-illustrated guide to Tewkesbury Abbey bosses in the gift shop really came in handy! I learned that many of the bosses depict scenes from the life of Christ. Here’s just one, the adoration of the magi (the Three Kings paying homage to the baby Jesus):

Others are a bit more random: Lots of figures playing medieval musical instruments make the bosses a great resource for historians of medieval music. There are pagan figures, as there often are in early Christian churches in England, including the fabled Green Man, as well as the Blue Man—who is news to me, and may actually not be a pagan figure, just a cool bit of decor.

I learned about the bosses being a later addition to the Abbey, from the late Middle Ages (14th century). See, Tewkesbury Abbey has really changed over the centuries, and continues to do so. Everything does.

Ch-Ch-Changes

Indeed, the Abbey is always a work in progress. A huge heating unit is one contribution from the Industrial Revolution. Looking rather like a Dalek from Doctor Who, this bit of Victorian high tech still heats the Abbey, along with its identical twin, although they now both run on gas rather than on coal.

During the English Civil War of the 17th century (not to be confused with the Wars of the Roses), Parliamentary soldiers, representing the Puritans who hadn’t shipped off to New England a couple of decades earlier, smashed anything decorative within reach. They tore down the original Chapel of Our Lady (the Virgin Mary) for being waaay too Catholic, and they also smashed statues, including many statuettes that were originally lined over the tomb of Hugh Le Despenser, as if it and its occupant hadn’t suffered enough indignity. You can still see the bases of the statuettes.

Saving the Best for Last

Tewkesbury Abbey is not only fascinating, friendly, and fun, but it’s also magnificent. I hate to cut myself off here, but there’s so much more to see that I can show you, much less write about. Do mouse over each photo for a larger image!

Don’t forget to become a Nonnie today! Info here!

Just out of curiosity, does Non-Boring Abbey have flying buttresses?

Fascinating - never heard of "bosses" before