Picking and Choosing

BITS OF HISTORY Ordering Online Nearly Two Hundred Years Ago PLUS History Without Effort

BITS OF HISTORY at Non-Boring History are historian Dr. Annette Laing’s posts about random items from her disorganized collection of junque antiquey thingies important historical artifacts. Ahem. Written off the cuff with little or no reference to academic history, so if you’re a professional academic historian and think I goofed? Get in touch.

There's a voiceover for today's post, in which I wheel out my Scottish accent for a bit. Paying subscribers will see the link at the top of the page. Note I changed the post title since recording. Part of the fun is I go off script. Oh, and support NBH before we become famous without you.

Note from Annette

Breaking News: I'm very excited by an upcoming book, We Have Never Been Woke by

and have pre-ordered a copy. Don't judge by the title, and don’t you dare judge his name. It will be fantastic for everyone, and it's published by Princeton University Press.Today, I came across a small collection of mid-19th century letters I picked up on eBay a few years ago, when I went through an odd phase of rescuing . . . no, not puppies . . . random historical documents being sold online.

Now, there are many ironies to this, starting with this: Is Non-Boring House really the best repository for primary sources (documents) we seriously hope to preserve? Um, no. No, it's not. Is it good to encourage eBay sellers to sell such things, thereby creating an incentive for nicking from archives? Again, no. My bad.

There are many, many, many, many millions more documents that live in attics, desk drawers, and basements than in proper archives tended by proper archivists. They can't all be saved. At least these docs will be put to use entertaining you!

These are letters about ordering stuff online in England in 1851. Obviously, “online” is not quite the right word for 1851, but hey, it’s the same basic idea: Buying from a manufacturer or third party through the mail. But we’re talking long before eBay or ye dreaded Amazon. So how did that work, exactly? That’s today’s big theme.

First, however, another story involving archives. Sort of.

History Without Effort or Pain

To start, let me give you some background and then tell you a bit of academic gossip involving historical documents (or maybe not involving historical documents) and a beach vacation.

These days, more and more cuckoos have snuck into the academic history nest. They come from new “interdisciplinary” subjects, which (unlike lovely old geography) I regard with the same skepticism as I do non-denominational churches (i.e. an excuse to lazily make things up in the absence of denominational discipline and knowledge), I'm frustrated that history departments hire these people, but we're a bit self-destructive that way, which is why I'm re-reading Sir Richard Evans’s In Defense of History, to arm for battle.

Some of these cuckoo interlopers argue that documents are not to be trusted, that they are mere propaganda representing elite views, or (and I just love the utter, clueless, ironic racism of this) white views.

Hmm…. These folk don't seem to grasp how historians are trained to read such sources, because often, they’re all we have, short of seances, to commune with the people of the past.

But the cuckoos say we don't need boring old-school thinking and tedious work in archives to commune with the past and write history! In fact, they’re misleading racist/sexist/classist things! No, they say, all we need to understand the past, are:

(1) “Theory”, readymade jargon-laden pseudo-intellectual templates, often created by trendy and flighty English and Education professors who, having been shown to be pretty bloody useless as scholars, claim to be all—knowing philosophers (all-knowing like Robin DiAngelo, a particularly profitable example, and no, I won’t be forgetting her sins anytime soon)

(2) Identity. After all, if a researcher is a [insert identity thingy of your choice] this provides said researcher with a direct psychic line to the people of the past who are assumed to be of that same identity. This identity instantly qualifies that researcher for writing about that past!* No dusty documents needed! -

*Not according to us proper historians it doesn’t.

Okay, let me try this approach! I have Identity! I can read Theory! Let me write history without documents or consulting historians who read documents and write books!

I’m a Scot whose ancestors, mostly landless farmworkers and maids, hail almost exclusively from the counties of Angus and Fife, with no new genetic input for at least 250 years (minimum) until I married Hoosen.

I was born in Angus, and although I lived in England from the age of almost four, I grew up in a Scottish household, my whole birth family are Scots, and I have, over the years, spent a good bit of time in the ancestral homeland, often with the family. All this gives me unique insight into the lives of my dirt-poor farmworker ancestors in, say, 1780. So let me just channel them.

After a hard day of digging potatoes or . . . um… growing oatmeal . . . we would find my folk haein a wee drink of . . . Tea? No, not yet, still mostly for rich people in 1780 (something, obvs, I was born knowing).

Whisky, then? Maybe. Unless they’re well intae Calvinism . . . My Granny did not approve of alcohol, and it was not allowed in the house. My dad took out his father-in-law and got him plastered one night, and my Grandad, emboldened by whisky, attempted on his return home that night to tell my formidable Granny that he was in charge now. That didn’t end well for him. Ooh, nooo.

But I digress. Well, my 1780 folk have a wee drink of something in front of the peat fire . . . No, wait, they didn’t burn peat in the Scottish Lowlands . . . Coal fire? In an ugly sparkly fireplace surround? With a carpet that looks a bit like vomit? Yes. I’m Scottish. I know these things. Because—again—I’m Scottish. Things have always been this way.

What we actually know about our own cultural background may not be what happened, as it took an English historian to gleefully explain to us Scots:

Everyone around the fireplace in this 1780 farmworkers’ hovel cottage is thinking Scottish thoughts and speaking in colorful dialect. “It’s a braw bricht moonlicht nicht the nicht, Bella, is it aye the noo?” [TRANSLATION: It’s a lovely bright moonlit night tonight, Bella, and the rest is nonsense like English people think we speak]

“Aye, it is, Mither. Ach, but eh’m fair starvit. Does anyone ken whaur I put thon Tunnocks Tea Cakes and Irn Bru eh got cheap doon Tesco’s the morn?” [TRANSLATION: Yes, it is, Mother, but I’m really starving. Does anyone know where I put those Tunnocks Tea Cakes (chocolate-covered marshmallow cookies) and Irn Bru (Pronounced Iron Brew, an orange-colored soda allegedly made with real steel girders) I got cheap from Tesco Supermarket this morning?]

“Ye daft besom! Neither Tunnocks Tea Cakes nor Irn Bru nor Tescos have been invented yet. It's all porridge and sheep innards fir the likes o’ us, while the local laird inhales the venison and salmon, the swine.” [TRANSLATION: You silly girl! Neither Tunnocks Tea Cakes nor Irn Bru nor Tescos have been invented yet. It’s all oatmeal and sheep innards for common folk like us, while the local landowner inhales . . . Ok. That doesn’t need translated.]

Okay, without knowledge from books and documents, I'm running out of material . . .Um . . . Let’s see . . . Life in a drafty wee stone cottage in 1780. Let me think. No TV. Not even my Granny telling her hilarious stories about my Auntie Jeannie, or about her time as a nanny in China in the 1930s. Not even the most basic chocolate biscuits (cookies) in silver wrappers that have been a staple of Scottish identity in my entire lifetime. . . Boy . . . This sucks.

Hey, let’s talk religion! I’m a Scottish Congregationalist by baptism, and OK, I haven’t practiced that faith since I was three, but I’m a Calvinist by birthright, so, um . . .

We’re doomed! Doomed, I tell ye!

OK, I nicked that line from the late, great John Laurie off Dad’s Army, the BBC sitcom set in WWII. But it works. And Laurie was also Scottish! He knew Calvinism! Let's tell each other we're doomed for the next few hours!

That’s a wee bit desperate, though, isn’t it? Okay, let’s see if Theory can help me. Here's some Theory book by an American professor of English with loads of identity thingies after her name on what used to be Twitter . . .

Oh, God, it’s word salad. I mean, somebody is taking the mickey here. I've thought that ever since the 80s when I tried to read French Post-modern philosopher and champion BSer Jacques Derrida. Let me see what I can pick out . . .

Ok, not happening. Maybe I'll make up my own Theory. If an English professor can do it, why not an historian?

Help! Help! I’m being oppressed! Come and see the violence inherent in the system! Ooh, the heteronormativity, the engines cannae take it, Captain! The implicit racism of most Scots being white because the sun never shines there, so we a’ look like lobsters if we sunbathe, and we are so complicatedly inbred to the point where we practically have third eyeballs in our foreheads . . .

Annette’s Wee Aside: Hey, no wonder my Scottish family warmly welcomed Hoosen and his pan-Asian contributions to our gene pool! Welcome, people o’color! Come awa’ in, darlin, have a wee cuppy tea, and marry ma daughter!

Okay, time to submit this for publication! How about calling it (Domestic) Culture, Whiteness, Spiritual Identity, Rural Discourse, and Tunnocks Teacake Deprivation among Scottish Farmworkers in Angus and Fife, 1780-1900, by Annette Laing (Certified Scottish)

So the gossip: Apparently some wokey theory-addled young person with a PhD in an interdisciplinary subject (on sale at WalMart or the university of your choice, right now), but claiming to do history, decided she should go into an archive in a sunny resort location, and have a shufty* around. Good idea! I endorse jumping into the archive in the deep end!

*Shufty, or shufti, meaning “to take a quick look” a word the British culturally appropriated from Arabic, where it’s spelled šufti, and apparently means “have you seen?” I wish to apologize to the world’s speakers of Arabic even though, um, they don’t care.

So Theory/Identity Kid got a grant, and off she went to find letters and diaries and whatnot to support the conclusions she had already drawn from Theory and her own Identity Insight.

Visiting the archive, she called up some promising-sounding documents. When they arrived, she sifted through them in horror. They didn’t tell any story she could recognize, or any story at all. They were very hard to read. Impossible to understand. Apparently impossible to use. Eek!

She returned the document boxes and folders to the archive staff, left the building, and never came back. Instead, she spent two grant-funded weeks on the beach, then flew home. There, back at her desk, she pulled some stuff out of her arse imagination, and wrote something that some journal published in an effort to look hip and an ally of any group you care to name.

So . . . Time we make cuckoos shape up and make like real historians, OR we require them to successfully explain to a committee of scary old historians* how their stuff counts for anything OR (failing that) make them move themselves and the books they own (both of them, both on pedagogy or Theory, neither read) into their own department, like Loadsacrap Studies, housed in an off-campus trailer, and vacate our history departments forthwith . . .

*PEP TALK FOR OLD HISTORIANS Look, most of you already do a pretty good job of the scary thing, or you wouldn’t have survived teaching: I remember one of my old professors, Bill Dorman, not an historian, talking about what happened when he brought his Sixties hippie values to his undergrad classes: “At first, I was saying things like ‘let the students grade themselves’ . . . And then I became a fascist.”

Old historians, I say you wear robes for the occasion of a reckoning with the cuckoos, and look like you mean it, no, I’m not bloody kidding. I mean the teaching robes like Oxbridge dons of old, not the silly American ones with bright colors and dead animals we wear at graduation. Robes really add to our gravitas, and if you came of age in the late 60s, you owe the rest of us for your part in messing things up, yes, you do, so please remember this is called being an adult, not being a sell-out. Gen X? Guys, this is our time to shine. Stop looking like a deer in the headlights. This is the moment we’ve been waiting for, right? Well, we're on. Put the guitar down, comb your hair, and get an appointment to remove those tats while you’re at it. Okay, I will comb my hair, and wear grown-up clothes in solidarity. Historians of color: I'm so sorry to ask you to do yet another bloody committee, but you know why. This should be quick, and imagine the cuckoos’ faces when they see you staring them down. I want to be there with popcorn when they tell you you’re not ethnic enough.

I hope that story of Beach Scholar is not true. But I bet it is. Work in archives is bloody hard but without it, and reading books based on archival research, what do we have? Well, a post like this, honestly, but as I never stop saying, even when I'm wearing my NBH hat, I cannot do what I do without archival experience, training by historians, and having read historians’ books.

Even if an archive is a few boxes of microfilm, a first encounter with primary sources (documents) and without training wheels is intimidating as hell. Look, I thought I had won the lottery as a grad student when, in search of letters written by British immigrants to 18th century America, I stumbled on an amazing resource: Dusty box after dusty box of microfilms in the basement of my university library, tens of thousands of letters written by British clergymen to London from practically every American colony in the 1700s. Bingo! Woot! A whole project without having to set foot on a plane to visit archives (although I later did that, too).

Eagerly, I wrangled one of the microfilm rolls onto a big unwieldy and poorly-lit microfilm reader. First, I looked in horror at the handwriting. Then I started, stumblingly, reading, or trying to read. Hey, the ministers’ handwriting was at least more legible than mine! Not hard. Yay. A start. But then I realized the reverends weren’t talking about how exciting it was to be in America. They weren’t even talking about religion. They were bitching about their salaries, and asking for more money.

Later that day, I anxiously stuck my head around the door of the office of my British history adviser, Dr. John Allen Phillips (a man from Georgia who had somehow been made a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society in London, how was that allowed?😁) I explained the problem. What do I do now, I said?

“Keep reading,” he said. “And wait for inspiration to strike.” I did and it did. But not at all in the direction I had wanted. So I ended up writing about ministers with status anxiety, and the congregants who saw them as mere competitors in a religious marketplace. “Reverend Gallstone’s sermons are so boring, and he's always complaining we don't pay him enough. I dread Sundays. Ooh, listen, the Quakers are in town! And admission is FREE! Let’s go check them out, and skip church tomorrow!”

You think I wanted to write about the history of religion? No. No, I didn’t. But here we are.

Welcome to archives. Big exciting places. Maybe I will take you guys around an archive soon. However . . .

What follows is NOT a real archival experience, but it does depend on my knowing a bit about times and places, and knowing to ask questions.

I'm using a tiny and coherent collection of letters I bought off eBay. I don’t know where it came from (apart from eBay, that is), so hopefully the seller bought it and didn't pinch it. I thought it would be fun to figure it out, right here at NBH, and then suggest how it might possibly be useful to a historian of 19th century Britain.

Shopping Lines

![Envelope, dated September 1, 1851, from Dr. Nicholas, Ealing School to a Mr. [illegible], 3, Paradise Square, Sheffield, stamped PAID](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ve3O!,w_720,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3f9cc1ef-0490-4cce-8728-5e2a180b7fc6_1165x878.jpeg)

![Envelope, dated September 1, 1851, from Dr. Nicholas, Ealing School to a Mr. [illegible], 3, Paradise Square, Sheffield, stamped PAID](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!TlAJ!,w_720,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F96be58d1-d9f3-4e25-bb10-7c52b8adbfff_1165x878.jpeg)

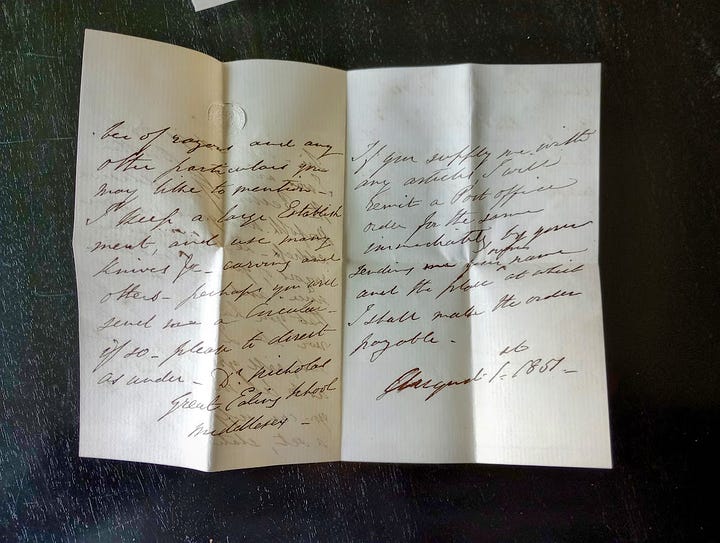

Okay, so what does the envelope tell us? Let’s start with that. First. I don’t assume this envelope has anything to do with the letters shoved in it, although, luckily, turns out it does. The stamp (literally, stamped, not a nice Penny Black or other 19th century stamp, disappointingly and surprisingly) gives the mailing date as September 1, 1851, and the news that it’s from Dr. Nicholas, Ealing School. So that’s a start! Can’t read the addressee’s name, but we’ll get to the address shortly.

Wikipedia tells me that Great Ealing School, founded in Ealing (West London) in 1698, later fell on hard times, and closed in 1908. In between, though, in the 19th century, it was regarded as highly as the legendary Eton and Harrow. So a posh school, then.

For much of that history, Great Ealing took boarders, and its Old Boys (alumni) make for impressive reading. First name that jumps out at me from the alumni list on Wikipedia is W.S. Gilbert. He was the lyric-writing half of Gilbert and Sullivan (like Andrew Lloyd-Webber, only with talent) who produced such early musicals (aka light opera or operetta) as HMS Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado.

W.S. Gilbert was born in 1836, and attended Great Ealing school long enough to become Head Boy, when he was likely 17 or 18. Holy Cow! This Dr. Nicholas dude wrote this letter while W.S. Gilbert was at the school! Maybe the great Gilbert was sent to post it in the nearest letterbox! Probably not, but cool thought.

At Great Ealing School, W. S. Gilbert painted scenery for the school theatre, and wrote his first plays. Cool! Today a school play, tomorrow The Pirates of Penzance!

But what about Dr. Nicholas? Who is he? Looks like the site of the demolished last home of the school is now named for the Nicholas family, who owned the school and were its most famous headmasters.

So, almost certainly, Dr. Nicholas was one of those headmasters, especially with that title of doctor, something he shared with the most famous English headmaster of the 19th century, Dr. Thomas Arnold of Rugby School.

Thomas Arnold was made super-famous by alum Thomas Hughes’s semi-autobiographical novel, Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Arnold was formerly a classics (Latin, Greek, that sort of thing) don (professor) at Oxford University. And like Arnold, odds are that Dr. Nicholas was an ordained Church of England clergyman: It was required of Oxford and Cambridge faculty at the time. Ooh, TMI! Here I go down the rabbit hole! Nope, I will restrain myself.

Okay, I found the letter from September 1, 1851, matching the envelope, but it’s not the oldest of the four. So let’s start with the oldest, from August 1, 1851.

Ooh, as I unfold the letter, I wonder what these letters are about! Is Mr. Thingummy of Sheffield a prospective parent? Is he trying to get a discount on the school fees? Is he complaining to the headmaster about a teacher?

Let’s find out.

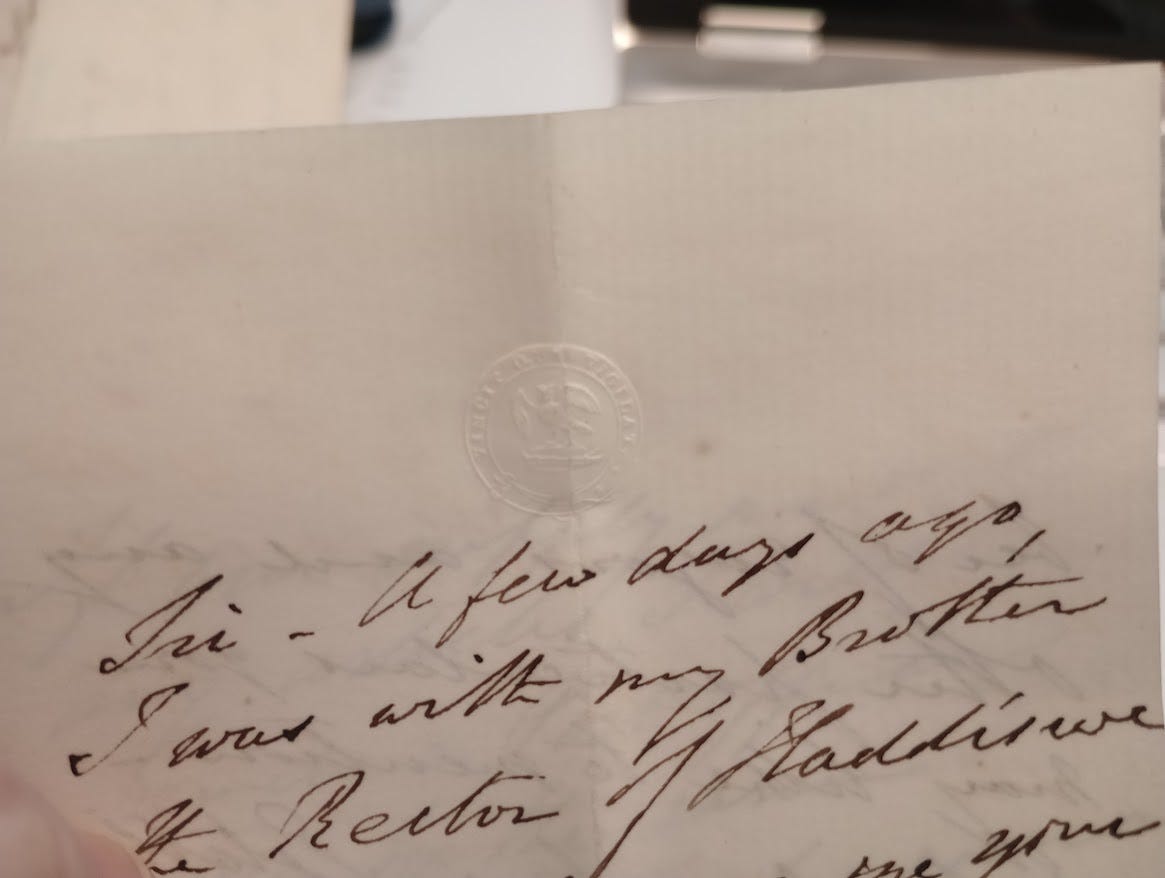

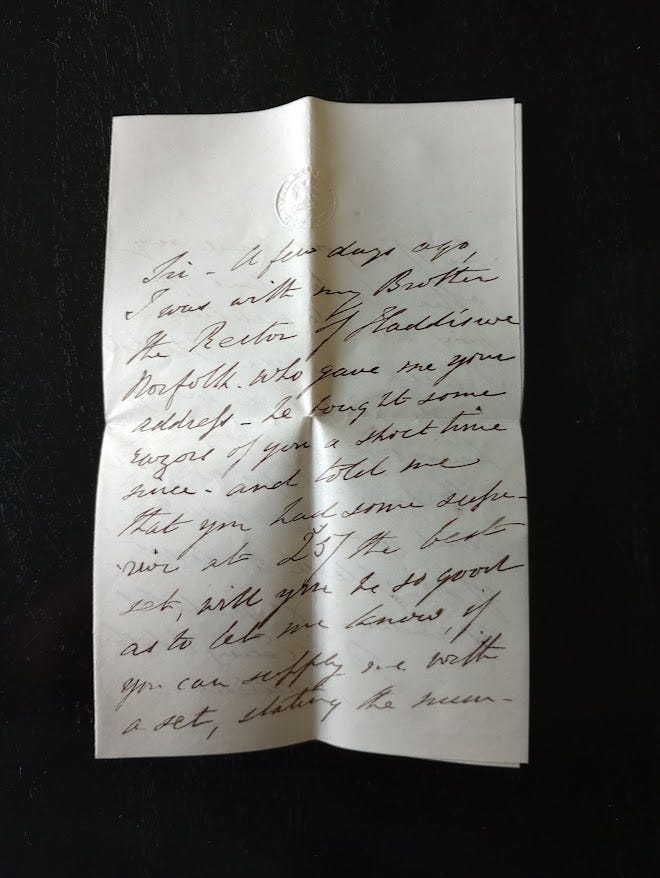

The notepaper has a tiny embossed logo I can hardly see. I learn—per Wikipedia— that when the school’s home developed dry rot in 1847, the school had to move to another building, this one named The Owls. So an Owl was adopted as the school logo, I mean, school crest. It was tiny on the notepaper, so all I could see was a bird, and I couldn’t read the Latin around it at all.

I used the magnify function on my phone to get closer . .

Yep, that’s an owl! Look at its face! And the Latin? Vincit qui Vigilat, which (Google says, and my vague memory of the tiny amount of Latin I studied confirms, sort of) means He Who Watches Wins. Cool! Don’t know what the owl is standing on, but good enough.

But what of our envelope addressee? Mr. Illegible, at 3, Paradise Square, Sheffield, and looks like that house is still there! A three-story Georgian building, and you can see it by looking up the address on Google Maps! Ooh!

Now then. Let’s look at this first letter.

Sir—

A few days ago, I was with my brother the Rector of Haddiscoe1, Norfolk, who gave me your address—He bought some razors of you a short time since—and told me that you had some superior at 25/- [shillings] the best set, will you be so good as to let me know if you can supply me with a set, stating the number of razors, and any other particulars you may like to mention—I keep a large Establishment and use many knives for carving and others—perhaps you will send me a Circular [catalog]— if so, please to direct as under—Dr. Nicholas, Great Ealing School, Middlesex.2

If you supply me with any articles, I will remit a Post Office order3 for the same immediately, by your sending your [illeg] name and the place at which I shall make the order payable—

August 1, 1851

On back: Case of Best [illeg] Razors

Case of best [illeg]

More razors—hard to read, even harder to understand what I’m reading on the fly, without more familiarity with the merchandise and the abbreviations being used. But, let’s face it:

That letter’s not thrilling. An order for a bunch of razor blades? My dreams of interesting content died. I mean who cares if the headmaster orders razor blades, unless he was a murderer . . .

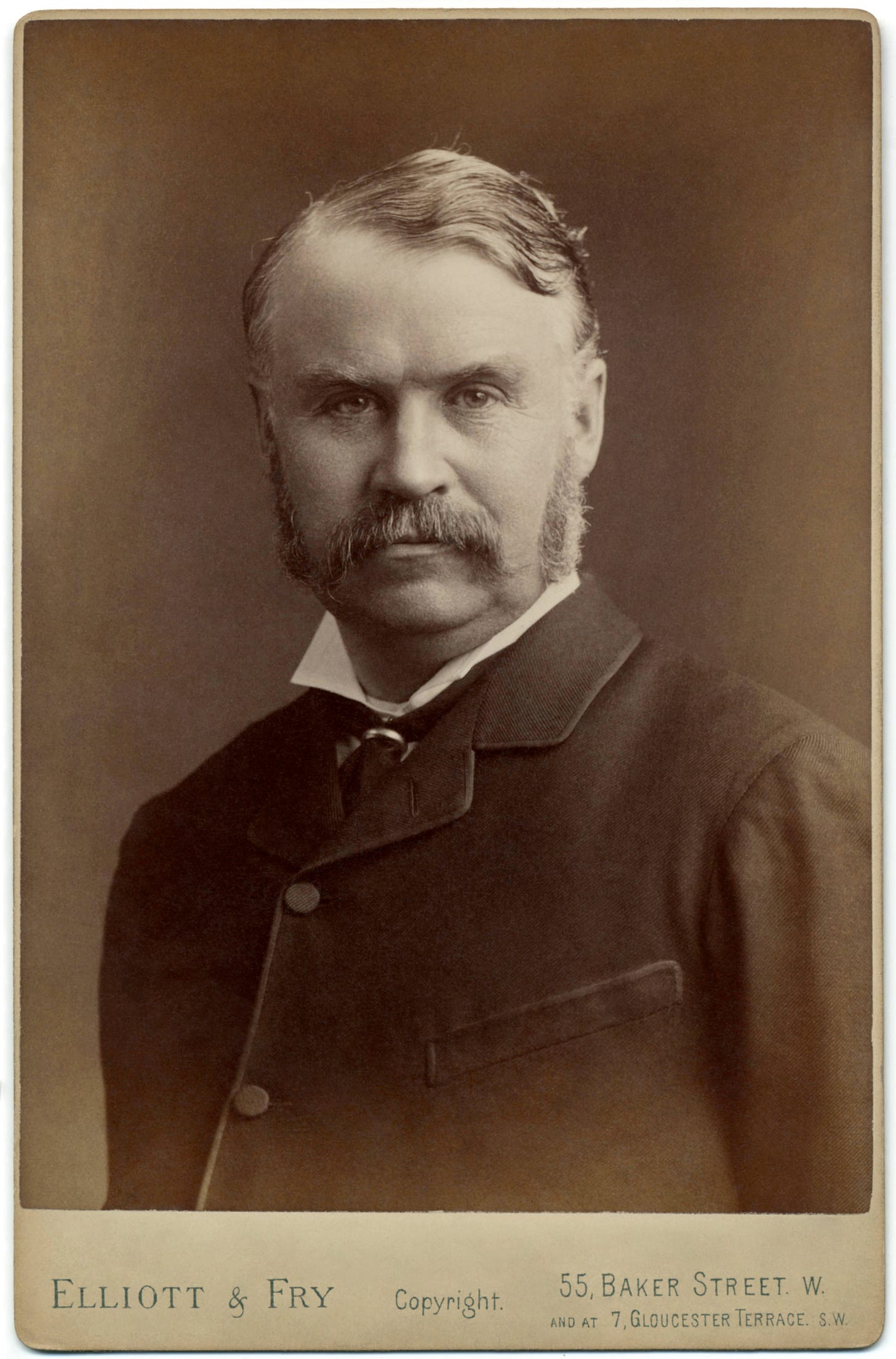

Wait! Hey, he needed them for the boys! The boys of Dr. Nicholas’s “large Establishment”, his school! W.S. Gilbert likely first shaved with one of these razors in the 1850s! Look, by 1880, Gilbert probably had to shave less, what with this pretty cool mustache and sideburns. Here he is!

So Mr. Thingummy is a merchant dealing in razorblades and other steel items, made in Sheffield, then a booming city dedicated to making things with new, modern steel. It’s strong! It’s awesome!

Now, what about the other letters from Dr. Nicholas?

Five days after his first letter, the headmaster fires off another letter to Sheffield, on August 6, 1851. I warn you, it’s not thrilling, but I want to show you why it matters, so please stick with me. I’m altering his uneven capitalization to reflect modern usage, for your comfort:

Dear Sir,

I should like to have a case of razors (12) best-black at 21/- [shillings] on receipt of which I will forward a Post Office order, by your letting me know to whom and where I may address it. [I assume he hasn’t yet had a reply to his first letter—A]

I should also like to have some good knives and forks—2 doz large, 2 doz do [ditto-A.] small, knives and forks for parlor, but wish first to know the prices, best white ivory handles.

Perhaps you will send two carving knives for approval with the prices—

I am, Sir,

Yours respectfully,

Francis Nicholas, Great Ealing Middlesex August 6, 1851

Personal Business

What’s striking to me is how inefficient this ordering process is. Compare it with ordering online today, checking off some boxes, and the software turning it into instructions to the warehouse staff. Voom pow, the stuff lands on your doorstep.

And yet, look at how humane this 1851 process is. The customer addresses the merchant as “sir” and signs off “Yours respectfully.” They are building trust, even before (I assume) Dr. Nicholas has heard from his supplier. He asks for carving knives to be sent “on approval” to be returned if they don’t suit him. This is not—I think— a big operation he’s dealing with, but a third party vendor in a small office building. That means trust.

Annette’s Aside: Now go read about life for workers today in big online ordering warehouses, and delivery staff. Hell doesn’t even begin to describe it. And this isn’t something that will sort itself out: From online behemoths to schools in Houston, TX (read about that, about that travesty, and no, good test scores mean nothing when the tests are tripe), humanity is being removed from every work environment, and it shows. I have a very, very, very strong hunch that mass shootings are not unconnected with this development. Do I have data? Nope. Hopefully some sociologist just took my hint, though.

Not so long ago, remote business transactions were done very differently, closer to 1851 than to now. As a kid at school, I was taught at age 11 in English class to write business letters not unlike Dr. Nicholas’s, by hand, neatly (I couldn’t ever get the hang of neatly, but hey) .

And this kind of personal service has not vanished— Non-Boring History mugs and shirts (available via that link!), although made (like everything else) in China, involved me dealing directly with Nick Mule, a real person, with whom I also spoke by phone, a third-party trader, eager to please and very friendly as well as professional.

People knowing people with whom they trade is at the least pleasant, and also very important. I have the great good fortune to live in Madison, Wisconsin, to know the people who grow my food, from Nico and Mel Bryant who produce my chicken, eggs, Thanksgiving turkey and so much more, to Darlene and Mary, my tomato ladies (who also supply us with cucumbers). Just a few days ago, at our local farmers’ market, Darlene kindly gave Hoosen and me a photo of us she had snapped at the market, in a fridge magnet frame.

These are very special relationships. This is one big reason why almost everything we eat—from flour to fruit to meat to herbs—is grown by people we have met. Relationships matter. People matter. You matter. Yes, you!

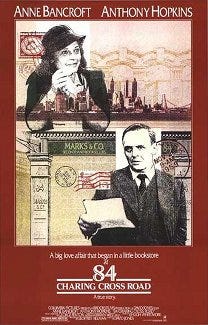

I realize I may be exhausting your interest in Dr. Nicholas’s requirements for small steel objects, but let’s look at what’s really going on: A growing cordial relationship. Not personal, but not entirely impersonal. I suddenly remember the best example of such a long-distance relationship between retailer and customer: The postwar letters of eager Anglophile New York scriptwriter Helene Hanff, as much interested in meeting Brits as in buying books from them, to London bookseller Marks and Co, and especially to bookseller Frank Doel, which are collected in the wonderful little book, 84, Charing Cross Road. The movie of the same name, with Anne Bancroft as Hanff and Anthony Hopkins as Doel, is also fab. Judi Dench is even in it! :) Just lovely, a fun and moving book and movie.

In the 18th century, people who wrote across the Atlantic for business often wrote and sent two or three copies of a letter, in case of sinking ships or misdelivery (often, all three letters arrived!) Now, in 1851, the professional British Post Office and Royal Mail, although around since the 16th century, was reformed to be more efficient starting in 1839, and especially in 1840, when the Uniform Penny Post was introduced: You could send a letter anywhere in Britain for the same low rate, one penny. By the end of the 19th century, there were up to ten deliveries a day in London, so letters became more like emails or even texts today.

On August 22, 1851, Dr. Nicholas writes again, and we immediately see the problem of his not keeping computer files, or typewriter carbon copies, of his letters to Sheffield. He has forgotten what the heck he ordered. He’s also still waiting to hear how to pay his supplier.

Sir,

I do not recollect whether I wrote to order the razors, but if I did not, I meant to have 12 razors at 21 /- Also, I said you might send a carving knife on approval. If you have a razor strop to suit the razors at a reasonable price, you may enclose it, with the bill and I will forward you a Post Office order for the same, by your letting me know where and to whom I make it payable.

I am, sir,

Yours respectfully,

Francis Nicholson,

Ealing, Middx Aug 22, 1851

But finally, an order is signed, sealed, and delivered, as we learn in Dr. Nicholas’s final surviving letter. Or is it? There are loose ends. Dr. Nicholas writes on September 1, 1851. Not that he is altogether happy. He grumbles about shipping costs.

Dear Sir,

I have much pleasure in forwarding to you a Post Office order for the Razors and knife and form which I received quite safe on Saturday evening, the charge for carriage [delivery] I think high: 2/4 [I can’t tell how much this is. Pounds? Guineas? Shillings and pence? Really not clear, and no time to dig, sorry!—A,)

I will thank you to return the enclosed receiptance [I can’t quite be sure of this word —A]—It is made payable to yourself.

Be so good as to inform me the price of your best Ivory handle knives for parlor table, per dozen, also of your dessert knives.

I am, sir, Yours respectfully, Francis Nicholas Ealing, September 1, 1851

The End of the Story?

If there were other letters, I don’t have them. So that’s that. These ones in my possession were presumably filed by the supplier in Sheffield in the one envelope originally sent by Dr. Nicholas, dated, as we saw, September 1, 1851, which suggests a completed correspondence. But I can’t be sure. I can never be sure. Maybe somewhere, there’s more. Perhaps I’ll just pop this lot in the mail to an archive in Sheffield. Maybe the archive is being closed because of budget cuts in a Britain being run by ninnies of whatever party. Maybe the letters are safer in Madison. Who knows? Not I.

1851: A Note on Timing

It’s interesting that Dr. Nicholas, in west London, writes all the way to Sheffield, in Yorkshire, in the north of England, to order mundane articles like knives and razor blades. I mean, London is FULL of shops. He’s not even apparently ordering from the manufacturer (whether he knows it or not) but from a merchant.

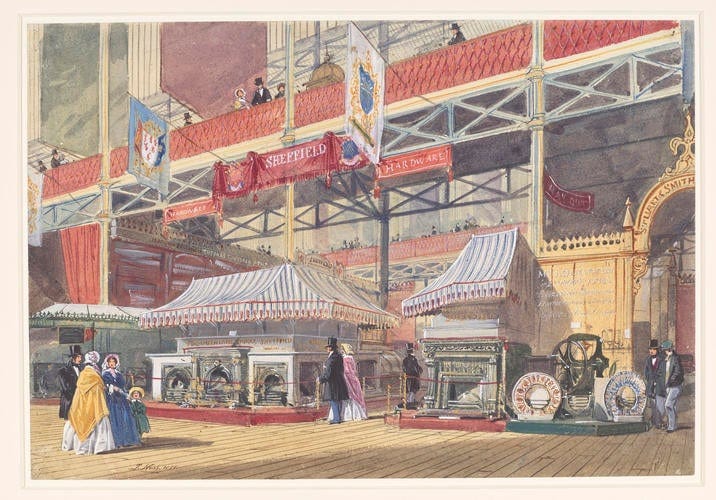

But he’s writing in a very special year: The Great Exhibition, the first ever world’s fair, held in the Crystal Palace, a giant greenhouse in London’s Hyde Park, May 1-October 1, 1851.

I love the 1851 Great Exhibition. I’ve written about it before. Not a paying subscriber to NBH? You don’t get better value for your $5 a month (with an annual membership) than you do as a NBH Nonnie. Join today for mindmelds with this historian!

The Great Exhibition was supposed to be an exhibit of the industrial products of all nations, but Britain had a huge advantage: It was the first industrial nation. Britain was to the world’s people what China is now, increasingly producing not only heavy industry, like ships and iron bridges, but masses of cheap, mass-produced new consumer goods that people suddenly realized they couldn’t live without .

Sheffield had become synonymous with high-quality steel goods. And these—large and small—were on display at the Exhibition to which Brits thronged by the millions, especially on trains, themselves a new and Brit technology.

Chances are that unless either he or his clergyman brother in Norfolk had a disability, both Francis Nicholas and his unnamed brother visited the Exhibition at least once—and likely multiple times. Nothing was for sale, but Brits could now see the future being created in those hideous industrial cities, like Sheffield, with their polluted air, unspeakable poverty, and scary big factories. And visitors to the Great Exhibition could imagine filling their homes with these goodies.

Here’s part of the Sheffield steel exhibit at the Exhibition, showing fireplaces and whatnot:

And one star of the show, in its own case, putting the later Swiss Army knife to shame was The Norfolk Knife in the Great Exhibition—despite its name, made in Sheffield. That link is to a Virtual Reality simulation of The Great Exhibition, by some anonymous soul, due to be finished soon. See more.

The Reverends Nicholas no doubt were thrilled by Sheffield knives at the Great Exhibition. I bet that’s where Dr. Nicholas’s brother from Norfolk first met the products and possibly the merchant he then recommended to his schoolmaster brother in London. Mail order was not new, but direct to consumer retail mail order was now about to take off, big time.

And we all know where that leads: Those blue and brown and white vans that pull up in front of our houses today. Good luck being able to exchange as much as a wave with the men and women who work so hard to bring us stuff: They’re being timed, supervised, surveilled. We don’t know them. They don’t know us. All that matters is the stuff, and the money it generates for someone, somewhere.

Non-Boring History is written by actual historian Dr. Annette Laing, formerly tenured professor of early American history at Georgia Southern University, until she told them to shove it in 2008. Now, she lives in Madison, Wisconsin, where she is not affiliated with the University of Wisconsin, Madison, but where she is hoping —and starting —to build community—so long as they don’t mind her tagging along— with the loveliest, kindest historians you ever met (despite them all also being dauntingly clever), led by Professor X, who is a total legend (The Gnomes have built him his own shrine at Non-Boring House).

Note

I simply ran out of time to dig around online and see if I could figure out the name of this merchant. If you want to give it a go, here’s a useful link to an 80 page document. If you don’t want to give it a go, then you’re a normal person. Well done!

Haddiscoe is a village near Norwich, in the county of Norfolk, in the east of England. This Rev. Nicholas would have served at St. Mary’s Church, which is still there if you want to look it up on Google Maps, and he lived in the nearby rectory, not sure if that’s still there, but if it is, likely privately owned now.

If I had any doubts that Ealing School is, in fact, Great Ealing School, those are now gone. Oh, and Middlesex, the county, is now totally part of Greater London.

More recently called a Postal Order, this is like a bank check, issued by the post office, and still used as a substitute for a personal check, a safer way to send money through the mail, and safer than checks (which can bounce) for vendors. Also, you don’t need a bank account with its associated charges to use them.