More Than One Wright Way (Part 2)

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Following Orville and Wilbur into the Wright World

How Long Is This Post? About 5,000 words, 25 minutes. 45 minutes if you read the earlier Part 1 of the story (and please do! There’s a link below the photo)

Continued from More Than One Wright Way (Part 1):

Not an Event. A Process. The Sciencey Stuff.

There’s an active airstrip at Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kitty Hawk, NC. So if you have your own aircraft, you can take off and land here, practically parallel with where the Brothers took off and landed in 1903 (Yes, I know it was Orville who flew. But this was a joint production, in so many ways).

As you land, notice the stone memorial markers showing the Wright Brothers’ first flight, made on one day in 1903. The markers are on a field surrounded by trees, and the markers are on grass, near the spruced-up, monument-topped, lawn-covered dune called Kill Devil Hill. It’s all very neat and tidy, very 20th century, but it wasn’t in 1903: This place was all sand, as we see in the original photos of the Wright flyer taking to the air. Aah… Just caught myself humming the theme to Lawrence of Arabia.

I was confused about many basic facts in the story of the Wright Brothers. In fact, I was Wrong, not Wright. I looked at the markers. There were four flights that day, not one.

The first flight? Just 12 seconds.

The second? Again, 12 seconds. The 3rd? 15 seconds. Well, big whoop. If I were Orville and Wilbur, I might have thought this was just a few lucky glides, pushed by the wind, not proper flight.

Last, but absolutely not least: Flight number 4, 59 seconds, just shy of an entire minute, 852 feet.

“That’s the one that really counts,” I told Hoosen with smug certainty.

Hoosen, being an engineer, firmly disagreed. That first twelve seconds did count as the first powered flight, it turns out.

Yes, I really am a historian. The PhD is in early American and modern British history, mind, and unlike your Uncle Fred the Civil War buff, academic historians freely admit we don’t know everything (unless we’re trying to get rid of Uncle Fred when he corners us at a party.)

So when Hoosen and I started out, I still had the vague impression that the Wrights were North Carolina residents, who just built a plane thingy, took it out, flew it, and voila! That was about the extent of their story so far as I knew. Maybe I did know better at some point. With a dad like mine, who had a degree in physics and a passion for aviation, I may have. Or I may have tuned him out. Or forgotten what I read as a kid. Our memories are finite. And we all have limits to our curiosity. I’m not having a bloody contest with Uncle Fred and his ilk, who always want to lecture me on the History Facts They Know That They Have Realized I Don’t, No Matter How Little I or Anyone Else Is Interested.

So of course I had the Wrights’ story Wrong. First, as we saw in Part 1, they didn’t just come up with the idea for the Wright Flyer from sheer genius. They were persistent, driven by curiosity and a desire to know, without certainty of success, and they had both time and money. They experimented, again and again, retreating to the barn they built at Kitty Hawk after each flight attempt to record data, tweak, repair, tweak, record data, and fly again.

But they learned from others, like Otto Lilienthal, the German pioneer whose successful glider experiments yielded data the Wrights gratefully used. Octave Chanute, the friend who gave them his biplane (two-wing) glider design. And Charlie Taylor, a bloke from Dayton: He and Orville developed the engine for the Wright Flyer over two years. Together.

The Wrights’ success was the product of a whole world of rapid change, a world that was becoming more familiar by the minute to us 21st century people. I hesitate to call this world the starting point of what we now call modern, because historians start counting early modern life from the 15th century, but the Wrights’ world is modern in the way most of us understand modern: It’s becoming recognizable.

1910: The Mass Genius of Teddy’s Foolish Journey

To understand what I mean, let’s think about the film I recommended in Part 1, about former President Teddy Roosevelt’s bizarre jaunt in an early Wright airplane in 1910, when fatal air crashes were very much expected.

Nothing about this film would have been possible twenty years earlier. The movie shows Teddy Roosevelt arriving by car at an airfield in Missouri, at an event organized by the Wrights. He’s easy to spot: He’s waving his hat, showing off to the crowd (as usual). His car looks quaint, even ridiculous, to us, a silly toy from long ago. But think like someone who is still getting used to the idea of cars: This thing moves without horses pulling it. Unreal.

Archie Hoxsey, a pilot (still a brand new occupation in 1910), now invites Roosevelt to ride along on his plane. We watch them converse. The filmmakers’ slide informs us that former President Roosevelt at first turned down Hoxsey’s offer to fly. But then, sensing how thrilled his fans will be, he changes his mind. Or maybe he was just pretending to turn the opportunity down, at first, in a show of fake modesty. Huh, Typical. This is a silent scratchy black and white film. People sometimes stand right in front of the camera, unaware of its presence or purpose. But look, again, through 1910 eyes: We see Teddy and Hoxsey talking. We see their lips move. This is astonishing.

Sound recording is also starting to be a thing in 1910. Within twenty years, film and sound come together in The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson. Jolson is a Jew, the child of the new wave of Russian immigrants, despised and feared by many Americans. In this very first sound film, he appears in blackface, and stop getting the vapors about this while congratulating yourself on our 21st century enlightenment. Here’s a nuanced article from twenty years ago about Jolson in blackface, the kind of nuance we aren’t allowed in most mainstream media right now—which is completely insane. History isn’t and cannot be about passing judgment based on a Tweet.

Back in St. Louis in 1910, Teddy Roosevelt is stumbling over the wires and ropes and frame as he takes his seat, right on the airplane wing. And then the film cuts to a hair-raising flight, the crazy aircraft hurtling over the field in sickening swoops. If Teddy was the first airsick president, the film doesn’t show us. Film, like photos, seems more truthful than writing, but that’s an illusion: We see what directors and cameramen want us to see.

What a strange new world this is, emerging so quickly. Milton Wright was born in 1828, when steam transportation and photography were barely getting started. No cars, no trains, no movies, no phones, no recorded sound, no light but candles and lanterns, and, of course, no flight—except rare and wonderful balloons.

Milton’s younger sons, Orville and Wilbur, grew into adulthood during this new, fast-moving period that the steam engineers and photographers helped plant: Electricity. Lightbulbs. Telephones. Sound recording. Radio. Motion pictures. Plus bicycles, and cars with internal combustion engines, the gizmos that made powered flight possible.

The change at the turn of the 20th century is a group effort by thousands, millions, known and unknown, pulling together, adopting and tweaking, thinking in modern ways. It’s not about lone “geniuses”. If the Wrights hadn’t come first, someone would have figured it out. The time was right.

Is there any inventor in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries, I just asked Hoosen, the engineer, that you would consider an actual genius, an absolute original? No, he said emphatically. He said Edison (the same name I'd just been wondering about silently) had a bad habit of taking the credit for others’ work. Alan Turing (the man who broke the Nazis’ Enigma code) was part of a team. Interestingly, the one possible exception he mentioned was Marie Curie, one of the few credited women-- but, Hoosen said, even she had Pierre.

They all worked with support, within the knowledge of their times, just like scientists and engineers today, and, for that matter, historians.

This got me thinking. How strange that we give such massive credit now to company CEOs, supposed lone geniuses who are happy to pretend they’re uniquely talented. That includes university presidents, practically all of whom now are grifters who profit massively, while most educated people who teach your kids in college are exploited and grotesquely underpaid, with predictably dire results for the quality of education.

There are no genius wizards. Clearly, we wish there were, or we wouldn't make such a fuss over nonentities in expensive suits. Remember: They’re little men hiding behind curtains, witches afraid of water. It’s the Winkies, the Munchkins, and the other good people of Oz who make Oz . . . Oz.

In short . . . The Wright story is about a lot of people. It’s huge. And if I had thoughts that visiting the museum at Kitty Hawk would finally tear me away from the comfort blanket of social and cultural history, and focus me on flight science . . . I was wrong. And Wright.

The Story Starts at Home

THE STORY STARTS AT HOME, the first panel in the Visitor Center museum at Kitty Hawk informed me in no uncertain terms. Just to drive the point home (groan), that statement was plastered over a big photo of the Wrights’ house in Dayton, Ohio, where they settled after migrating back and forth across the rural Midwest for years. This working-class neighborhood was where Orville was born, four months after the family moved.

For Orville and Wilbur, the story that defined their lives began with the family, in 1878, when Milton brought his two younger sons a gift, a wind-up flying toy, like a helicopter. It fascinated the lads.

Look, once fascination is implanted, once you match the kid to a passion, even one you don’t have yourself, and almost every kid is capable of a passion, teaching and learning are easy.

An Annette Aside: Forget those Education “experts” who, not being educated in history themselves, not having a single bloody qualification in anything but “Education”, think history is all about “mastering” and “retaining” “information”, stating “learning objectives” and passing bloody tests and “assessments”. They (and politicians) are directing what happens in public and many private schools, and they’re now trying to direct what happens in state universities (more about this soon, oh, indeed, because I am really angry about this.) To quote Dr. Jon Smith, Professor of English at Simon Fraser University (and you really should listen to this NPR piece about the day he had had enough of BS, he’s magnificent), we had education for 2, 000 years before we had education professors.

Are you offended by this criticism of experts in Education (the subject)? The Head Complaints Gnome at Non-Boring House looks forward to receiving your letter. In unrelated news, it’s cold this winter, and the Gnomes’ basement fireplace needs more fuel.

Annette would like to remind you that showing what it means to look at things differently, depends on your willingness to entertain the possibility of looking at things differently.

Once the Wrights’ passion for flight took, um, flight, it was all about trying, failing, learning, trying again . . . The Brothers weren’t trained engineers. Neither attended college. They were tinkerers, inventors, small businessmen with an expensive and all-consuming hobby. They had grown up in a home where actual learning—not just at school—was encouraged, and that made all the difference. It also helped that they had two highly-educated parents (not just highly-skilled, not just having a certificate, but educated) and an educated sister. Yes, sister. As Hoosen said later, “A lot of this wouldn’t be possible without supportive families.”

The Wright Sister

I had never heard of Katharine Wright until I found her in the museum in Kitty Hawk. It’s really a great pity she wasn’t here on The Big Day. She stayed back home in Dayton, while her brothers played on the beach in North Carolina. The youngest of the three younger siblings, Katharine was just fifteen when her mother died. It’s the usual 19th and early 20th century story: As the girl, she stepped in to do the domestic stuff.

But Katharine was a Wright, so she didn’t just do the “usual stuff”. She did the Wright stuff. She enrolled in Oberlin College, a pioneering Victorian institution, Ohio’s pride, that accepted women (of all colors) as well as men (ditto). It was not the sadly overprivileged place it has become.

Katharine was completely involved in her brothers’ flight project. At Kitty Hawk’s museum, I read this quote from a letter she wrote to Milton in September, 1901. Wilbur was frustrated and fed up, she says, because some of the data he and Orville had collected on gliding from pioneer Otto Lilienthal wasn’t working for them. Their friend and cheerleader Octave Chanute (the biplane design chap) suggested that Wilbur address the Western Society of Engineers. Katharine picks up the story:

"Will was about to refuse, but I nagged him into going. He will get acquainted with some scientific men and it may do him a lot of good."

Wilbur got a massively positive reception from the conference, and his speech was reprinted in journals around the world. On that day, he realizes that, little though he thinks he knows, he’s the expert. Wilbur returns to Dayton with a spring in his step. His confidence is restored, and so is Orville’s. They return to their experiments with new enthusiasm, working on a wind tunnel.

Never discount the importance of confidence. Katharine, Oberlin graduate, was now a ticked-off feminist. She became a teacher, and was paid less than her male colleagues, and given the crappiest classes, what a shock. She bolstered her brothers’ confidence, and her own, when she ran their small business while they were in Kitty Hawk, managing their affairs while acting as a sounding board for their ideas on flight. Katharine’s own favorite modern gadget? Probably her bicycle. It gave her freedom, as it did for so many late 19th century women. And confidence to find her own way, alone. Oh, and did I mention? What the Wrights learned about flight owed a lot what they learned from the people who came up with bikes. Think of the bike parts I spotted on the Wright Flyer replica back in Indiana.

Here at Kitty Hawk, I found some science at a level I can grasp, in part because I can ride a bike. Read this, from the exhibit:

The brothers make a connection between flying and cycling (the new rage): it's about turning. To stay in control while turning a bicycle, you have to lean your body to stay balanced. The brothers think they can apply this same concept to help control a flying machine.

Not that I understand the principles involved, but still, it’s a start! And think of everyone who made this revelation, this moment of education, possible, from historians, physicists, public historians (museum professionals), bike inventors, and the Wrights themselves.

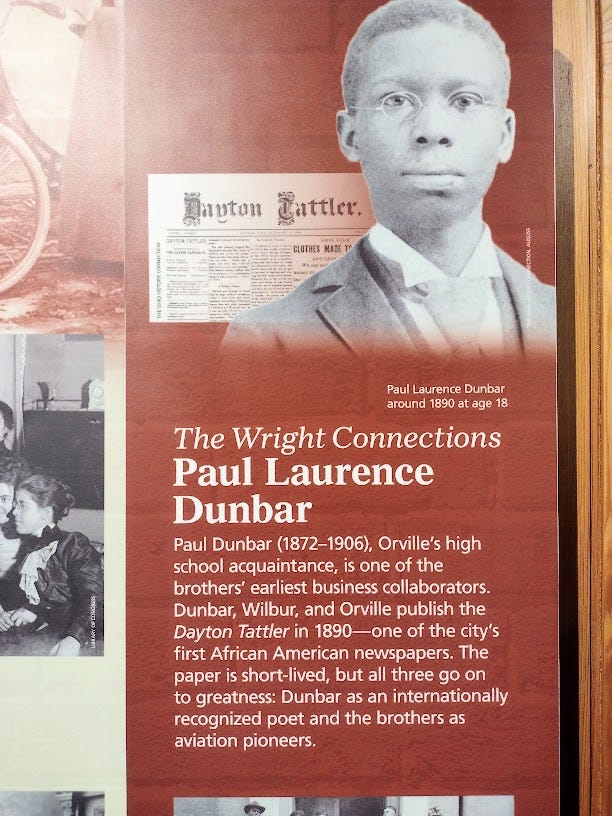

I spotted this picture in the museum at Kitty Hawk. It’s him again, the bloke from the Wilbur Wright Birthplace Museum. I remembered about the Wrights’ printing his newspaper, Dayton’s first aimed at Black citizens. But a poet? (And internationally known? I didn’t really take that in at the time. I’d never heard of him.)

Homing in on Dayton

What happened at Kitty Hawk was hardly the glorious end of the Wrights’ story. It was the tenuous beginning. Now, the Wright Brothers went home to Dayton, Ohio, and started experimenting all over again, flying over a field that is now, by no coincidence at all, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

“There’s a load of Wright Brothers museums in Dayton,” I said to Hoosen. “It’s insane.. We couldn’t possibly do them all.” Who apart from a total obsessive would take off a week to vacation in Dayton, Ohio? [Team UK: Think Birmingham]. Even my dad never suggested it: His favorite American place was Disneyland. Later, I mentioned to NPS Ranger Kathleen that my readers probably wouldn’t plan to spend a week in Dayton. “Well, they should!” she replied cheerfully. I like Kathleen’s spirit.

However, you can never “do” every museum in America: There are hundreds of thousands of them, all competing for funds, and our time and attention. I said to Hoosen, “If we can only do one, let’s do the National Parks Service museum. Oh, wait, blimey, the NPS has two. One’s at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, and it sounds like it’s more technical. Do you want to go there?”

No, Hoosen said. He knows how flight works. It’s all the other stuff he’s interested in learning. Phew, what a relief!

I asked the Google to direct us to the National Parks Service museum. We ended up at some place called Wright Brothers National Museum, far from downtown. In the parking lot, I looked at the building suspiciously, searching and failing to find the NPS logo. Then I looked up this place on the web. “This one looks like it might be really good,” I said. “But this ticks me off: It’s not the NPS museum. We’re in the wrong place.” I do hate when museums call themselves “National” when they’re not run by the federal government. They often charge high admission to places that the NPS would offer for cheap or free. I was now determined to get to the right Wright museum. Turned out to be a good decision, but not because it kept us on the Wright track. Not at all.

Lessons in Dayton, Ohio

The photo of the Wright brothers being photobombed by some bloke at the very top of this post may have had you doing a doubletake. I did a doubletake, too, when I saw it, in the reception of the museum at Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, the NPS museum we finally found.

Text to the right of the photo reads: Celebrating the legacies and creating an understanding of three exceptional individuals: Wilbur Wright, Orville Wright, and Paul Laurence Dunbar.

I’m sorry . . Paul who? Wait, the bloke whose newspaper the Wrights printed? The poet? He wasn’t an aviator too, was he? I thought of the museum’s name at the entrance: Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. I cringed. In that moment, this photo felt like a well-meaning but incredibly cack-handed way to include a local hero in a museum about the Wright Brothers.

Just now, here at Non-Boring House, I looked up the museum on a city web site. There, it’s called Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center. On the NPS app, which I had also consulted on the day, well . . . Let’s just say it’s very confusing. And if you know of the Wrights (who doesn’t?) but never heard of Paul Dunbar (most of us haven’t), then what’s going on here is a complete mystery to the casual visitor, which is most of us. Now I was curious to see what kind of case the museum would make for giving this Dunbar dude a starring role.

I learned from folks in Dayton that there are a lot of museums here because everyone wants a piece of Wright tourism. By the time the National Parks Service arrived (and let’s be clear, the NPS sets a high museum standard these days) others had long ago grabbed most of the best artifacts.

And, to confuse us further, this isn’t a proper NPS Museum: It’s a “public-private partnership” that politicians have foisted on the National Parks Service. The museum was created in conjunction with one or more local museums. Local museums have very different cultures and priorities from the NPS. As you can imagine, such an arrangement might have problems. We might, indeed, have ended up with a museum equivalent to a horse designed by a committee: A camel. But— get this—-I’m so glad this is where we ended up, and I will explain. For now, just know that if a museum confuses you, you almost certainly aren’t the problem.

I Want to Ride My Bicycle

We had arrived at what I have finally figured out was Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park’s Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center (or, to borrow from Hoosen, Jr’s girlfriend, Way Too Long Of A Name Museum). It’s smack dab in the Wrights’ working-class neighborhood, now known as Dunbar (how the heck would I know that? I know nothing about Dayton. Hells bells, life is TOO SHORT to know everything about everything, and visiting Dayton, oddly, has never been on my bucket list.)

This neighborhood is where Orville and Wilbur and Katherine grew up. It was very unlike the rural 19th century settings in which their two older brothers were raised. And after high school, the boys stayed right here. Inspired by visits with their father to church publication print shops, Orville and Wilbur opened their own print shop.

But then bicycles took America by storm in the 1890s, and the Wrights saw a profitable new trade beckoning: Bike repair. Then they realized that building luxury bespoke bikes for well-off clients would be even more lucrative. As their bike business boomed, they closed the print shop, in 1899. The boys had found a surefire way to fund their flying experiments, by building bikes, another brand-new technology.

1903, the year of Kitty Hawk, was not really The Big Year of Flying for the public. Newspapers exaggerated what had happened on The Day, but the public yawned, bored with being misled about flight achievements that turned out to be hoaxes.

Now that the Brothers had got down the basics in North Carolina, they came home, and rented a field in Dayton to continue their experiments. There were accidents, and it’s a miracle that neither of them was killed, but they got to the point that they could fly in circles for nearly forty minutes at a time. They now offered their invention to the Army (for a moment, I thought, “Why not the Air Force? Oops). The Army brass wouldn’t believe them, and certainly wouldn’t contract with the Brothers for airplanes until they could inspect the machinery close up. Afraid of being ripped off, the Wrights refused to show the Army anything.

And then the lads didn’t fly for three years. Three years, while European aviators began to catch up with them. Finally, Wilbur flew at an air show in France in 1908, showing how reliable, how stable the Wrights’ plane had become, how much better than what European aviators had so far produced. This is what it looked like on the day, thanks to film:

And now they were The Wright Brothers.™ For better or for worse, we’re taught to draw a line under that. My message today: Please don’t.

A Whole New World: Paul Dunbar and the Wrights

It’s Hoosen I have to thank for nailing the problem, ever the engineer zooming in: “This museum has the wrong name,” he said. At the museum, he had become as fascinated by Paul Laurence Dunbar as I had. Dunbar’s inclusion no longer seemed awkward, forced. It now made glorious sense, but that only happened when we stopped and rethought what we were actually learning here.