More Than One Way to Travel (1)

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Different Roads to Understanding America and History High in the California Mountains. And Cannibalism.

How Long is This Post? 3,500 words, or about 15 minutes

The most memorable tale of early migrants to California is a horrific story of cannibalism.

Well, that got your attention, didn’t it?

The Donner Party, a group of more than eighty wagon migrants from the East and Midwest, including people originally from Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, and Belgium, came to California, a year or so before gold was discovered. They came West in 1846 to what was then Mexico, looking for land, or a healthier climate. Their elected leader was George Donner, hence the name.

But the journey didn’t go as planned. Trapped in the brutal winter of the Sierra Nevada mountains on the edge of California, they turned to cannibalism. That made them a subject of horrified fascination to Victorian America, and, a century later, the butt of jokes in California, where the fate of the Donner Party is part of elementary school curriculum.

Look, I love fourth graders [UK: 9 year olds]. They’re not innocent wee ones, they’re thinking, eager, and ghouls. Most adults are ghouls, too, they just pretend not to be—the hypocrisy is stunning. In a radio sketch I remember, a restaurant host called for “Donner, party of 80”, and then learned that they were now only forty in number, and they already ate. Hardy-har-har. And then there are the Donner souvenirs, like this T-shirt.

I’m not here to rain on the humor parade, or be a pompous ass. I have a tongue-in-cheek Donner Dinner Party magnet on my fridge, for heavens sake! I’m a firm believer in “inappropriate” (gack, choke) history for kids, because that’s how you get them interested.

They don’t give a crap about dates and “important” facts, and neither do you. I have no time for stick-in-the-mud nonsense about history. And I have dedicated my life to history: I’m a paid-up historian, not a dabbler.

But despite my cheery tolerance for the Donner jokes, I have to tell you that once we read past textbook generalizations about the Donners, we forever feel uneasy. I’m planning to do one of my Tales posts as a gateway to history that puts the Donners in context, that goes beyond our very human fascination with the grim story. Consider today a gateway to that gateway, which I hope makes sense.

Bear in mind that this is only what Brits call a “taster”, a quick sample. And it’s still more than most people know.

The Donner Party was misled by a charlatan, a bestselling author named Lansford Hastings, who advertised a “shortcut” to California through modern-day Utah that neither he nor anyone else had actually traveled.

For the Donner Party, this was disastrous: The group arrived too late in the year to cross the formidable Sierra Nevada mountains into California. Trapped in up to 14 feet of snow, they ran out of food. Indians in the area spotted them, and tried to help, tried to bring them something to eat, but the migrants were terrified of Indians, thanks to sensational newspaper accounts, and shot at them.

So if you are inclined to take sides in history, like you’re picking teams, here’s an out: Indians good, Donners bad. But have you noticed? When we do that, we always pick the winning team, side with the popular people. A hundred years ago, it was the migrants. Now it’s the Miwok people, who certainly are the heroes of the moment I just described. But this is not how academic history works: Sure, historians are human, we’re not neutral, but we try to understand all perspectives. Why and how that is, why it’s helpful to everyone, is one of the things I try to get across at NBH.

So join me now by Donner Lake, in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, on a beautiful October day. We’re right off the I-80 Freeway, a long and winding road to the Central Valley of California. Today, driving from Reno, Nevada, on the eastern side of the mountains, to Sacramento, the capital of California, on the western side, typically takes about two hours, as it did for Hoosen and me. Donner Memorial State Park is about half an hour into that journey. Even today, the 1-80 can be a fairly tricky drive all the same, especially for trucks. In the winter, sometimes, snow in the mountains can shut down the freeway altogether. Yes, even in the 21st century.

Choosing Stories, Changing Times

There’s a museum at Donner Memorial State Park, a nice modern one, but we’re not talking about it today. I’m saving it for Wednesday. However, what I’m telling you about today draws in part on what I learned there.

Donner Memorial State Park says in its name that it’s a memorial. But to whom?

Laing, don’t be stupid. Obviously, it’s a memorial to the Donner Party.

That’s what I thought, too. But it turns out that the answer to that has never been entirely straightforward, and never will be. Today, though, the answer is both clearer and more complicated than ever before, and I want to show you what on earth I’m talking about without making your brain hurt. Promise.

So slip on your NBH T shirt, grab your coffee in your NBH mug, and settle in your comfy chair (NBH furniture? Could happen).

Let’s start in this place, a few yards to the right of the Visitor Center in the photo above. It’s a warm October day in California, pleasantly warm even here in the mountains, where a couple of months from now, there might be anything up to 17 feet of snow. I’m standing just a few feet from where once a cabin stood that gave shelter to some of the Donner Party in that dreadful winter of 1846-7. And I wish I’d asked Hoosen to photo me standing next to this statue so you can see how huge it is.

Let’s get something straight: The statue is NOT of the Donner Party. It’s an imaginary 19th century family of generic white migrants to the West, with Dad at the forefront, sticking out his chest, portraying the men who came by covered wagons as brave visionaries. Mum cranes her neck from behind him, while kiddo looks to Dad for guidance.

Hello, NEW CONSERVATIVE READERS: Don’t worry. We’re not about to get all wokey on you. As long-time readers of Non-Boring History will tell you, everyone gets challenged here, and often in very surprising and rewarding ways. Stick around, and you’ll see what I mean.

Hello NEW LIBERAL/PROGRESSIVE READERS: Same message, basically.

Here’s what the plaque on the plinth has to say:

VIRILE TO RISK AND FIND; KINDLY WITHAL AND A READY HELP. FACING THE BRUNT OF FATE: INDOMITABLE — UNAFRAID.

Yeah! 🇺🇲

Wait. Um, what?

That kind of lost me, too, somewhere between “VIRILE” and “INDOMITABLE — UNAFRAID”. What does that even mean? Still, though, the language, however weird, is all very manly, isn’t it? All sort of chest-stuck-out. No surprise, since this was put up in 1918, when manly themes were still hovering in people’s minds in the US (and the UK).

But 1918, the last year of World War One, marked a turning point for most Americans and Brits. Hundreds of thousands of earnest and patriotic manly young men had been blown to bits in the trenches of the First World War for no clear reason.

To most Americans, and most Brits of 1918, the sacrifice was too much, the reasoning not enough. In 1915, two years before America officially entered World War I, appalled Americans read about the slaughter in France in horror. The most popular song that year was I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be A Soldier. And yet, within three years, American boys were fighting in Europe. And within a few more short years, the culture had swung back again, away from war and a spotlight on “manliness”, and toward “Never again”.

Yes, indeed, cultures, how people think and act, can change that fast, especially in times of upheaval: Think about the past three years. Think about the Great Resignation. See what I mean?

So, here’s the statue’s dedication day in 1918, happening in the middle of all that cultural change.

That shift in cultures between 1914 and 1918 led to heated arguments over how this statue would appear, and who it would be a memorial to.

Let’s see who was involved, and why the statue ended up the way it did.

While a man is the lead figure, it’s interesting that a woman and even a child are featured on the statue. Turns out, that was the idea of the artist. I wish I knew more about his reasoning. Was he fed up with “manly” culture? Was his old granny a veteran of the wagon trains, so he didn’t want to leave out women? No clue.

What I can say is that this was not what Charles McGlashan, the historian involved, had wanted. He had wanted the statue to represent the Donner Party, rather than “pioneers” in general. And that makes sense: A pioneers statue could have been anywhere in California, many of them places like Sacramento that were much easier to get to in 1918 (or now) than a spot high in the Sierras. But this spot was where the Donner Party starved, only seventy years before. A memorial to them here made sense.

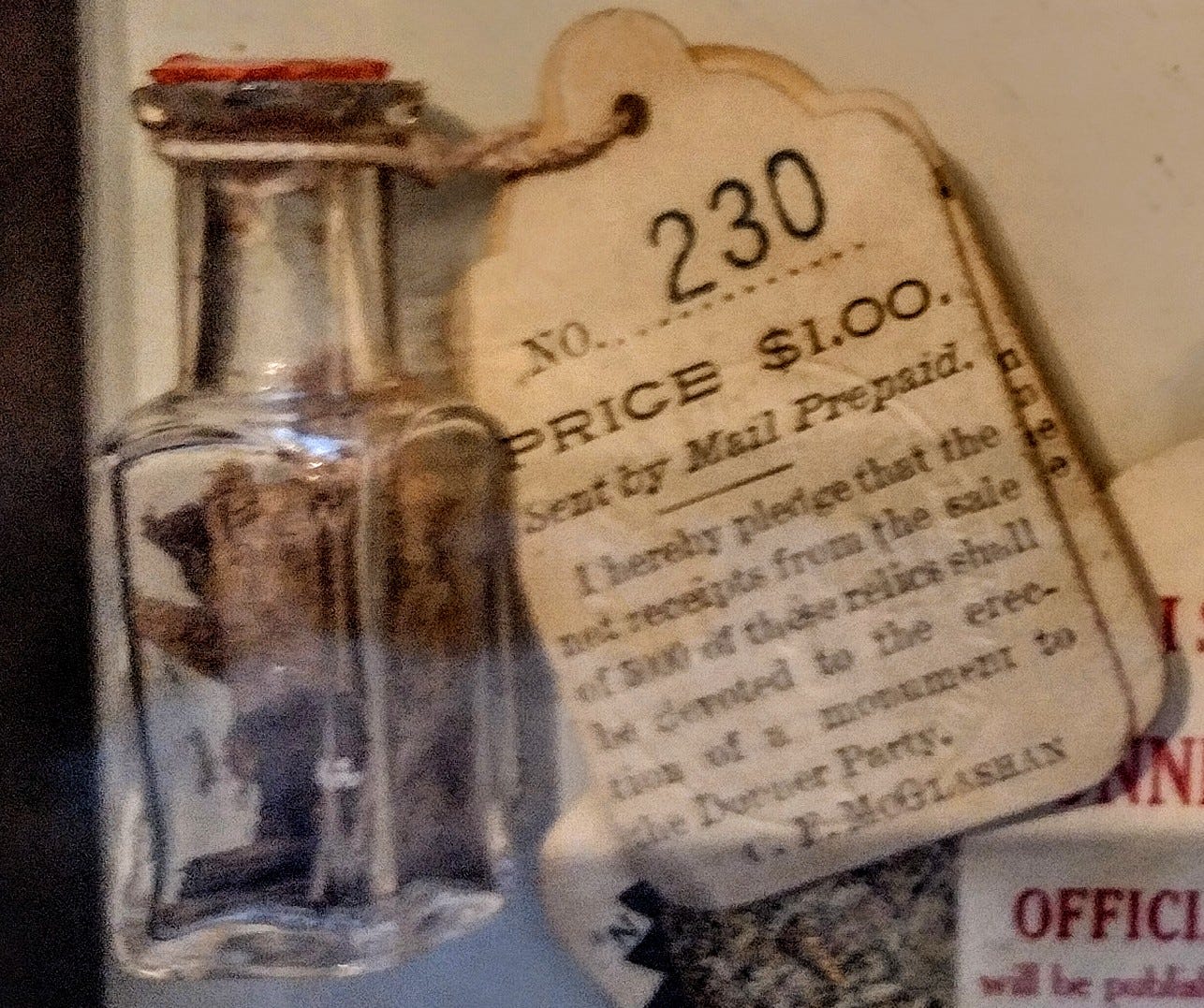

McGlashan was not an academic, not a university-trained historian, but he was a popular historian. He had written a bestselling book about the Donner Party, so no surprise that he was seriously committed to a Donner memorial. McGlashan personally raised money for the project by selling five thousand little glass bottles for a dollar apiece, each containing slivers of wood from the last few remaining logs of the last remaining cabin that had sheltered members of the ill-fated Donner Party. The museum here at Donner Memorial State Park observes that “Today, this could never happen.”

True. . . But what a brilliant idea it was! Oh, heck, historians aren’t archaeologists. Who cares about a small stack of logs? Chop up a few old bits of wood to raise money to tell a good story? Works for me!

Wisconsin-born Charles McGlashan’s other big interest in life was hating Chinese immigrants. This made him very much a man of his time: There was a lot of hating of immigrants and, especially, immigrants of color between the 1880s and 1920s, a time of massive immigration. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe (especially to the East Coast), and from China and Japan (mostly to the West Coast), did much of the work of building modern America, taking badly-paid and dangerous work in factories and mines, and building railroads. This brought them into conflict with native-born working-class whites, and competition for jobs with decent wages blended easily with racism.

While living in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Charles McGlashan formed the Truckee Anti-Chinese Boycotting Committee (and later belonged to similar groups elsewhere). He argued that working-class white Americans were losing jobs to immigrants, and advocated attacking Chinese settlements, and humiliating Chinese men by cutting off their cues (pigtails).

He absolutely wasn’t alone, as we will see. We can go shout at his grave, or we can just accept that this was how things were, and ask why that was.

Anyway, on the memorial issue, McGlashan didn’t get his way: Others were determined to have a memorial here to all wagon “pioneers” as they arrived in California, not the Donner Party. A powerful group had taken a great interest in the memorial projects: The Native Sons of the Golden West

About the Native Sons

The Native Sons of the Golden West were (and are) an organization of the descendants of the “pioneers”, and they were among a wave of ancestry-based societies that sprang up as a backlash against immigration in the last part of the 19th century. The most famous of these? Probably the Daughters of the American Revolution, of whom you might have heard.

In 1918, while the Native Sons were (surprisingly) keen on rights for the Indigenous population, they were otherwise explicitly racist, opposing immigration of Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican people. Yes, Mexicans, despite the fact that California was part of Mexico until 1848, just months after the Donner Party disaster.

Even today, the Native Sons limits membership to people born in California. I have known a number of men with deep California roots who certainly qualified as descendants. They would rather have had their fingernails ripped out than join the Native Sons, on principle, given its history. Indeed, a popular rhyme I recall being chanted by California friends about the “Pioneers” was “The miners came in ‘49, the whores in ‘51, and when they got together, they begot the Native Son.” (Actually, Sacramento has always been more boring than that suggests, and for evidence, I give you my two-part post on Ledyard and Margaret Frink, the earnest and respectable middle-class couple who were among Sacramento’s first settlers.)

The Historian v. The Native Sons

Charles McGlashan thought differently than historians today, but he did have a historian’s eye for a good story.

Rather than a monument based on generic pioneers, he wanted the memorial at Donner Lake to focus on the Donners. He lost this battle, partly because heavy patriotism was still in the air in 1918, but mostly because the Native Sons of the Golden West were big into ancestor worship, and they outnumbered him.

It was hard for the Native Sons to feel patriotic and proud about a bunch of hapless people who got conned by a grifter, lost their way, fought each other as they traveled across the West, and ended up eating one another.

Let’s pause a moment and think about this, because I promise you won’t be able to unthink it. Let’s stop thinking like 21st century people for just a moment. In the 1840s, the Donner Party’s story of desperation, failure, weakness, and horror was read in newspapers by shocked and appalled Americans, including the parents and grandparents of the men and women who built the Monument. Californians were fascinated by the Donner Party, but they didn’t want to own that story.

I mean, who would you want to be descended from? Tragic cannibals . . . or a heroic, manly figure with his chest stuck out, “FACING THE BRUNT OF FATE: INDOMITABLE — UNAFRAID”? Yeah. Exactly.

But things are only starting to get interesting, and if you’ll stick around at NBH, we will chat about it: The wagon people weren’t exactly as the people of 1918 imagined, or as they feared, or as we fear. In reality, they were disarmingly human, and recognizable as, well, people, with all of people’s flaws, prejudices, and weaknesses.

And they will surprise you. When I think of wagon pioneers getting their first sight of the Wasatch Mountains in modern Utah, which on one infamous route, they would need to cross, even before they got to the Sierras, I don’t think of manly men who jutted out their chests and laughed. They didn’t exist.

No, I think of the Dads who had brought their wives, kids, animals, and worldly goods over a thousand challenging miles. They took one look at those peaks, fell to their knees, and sobbed. They really did.

As we entered the museum, I noticed this small sculpture, which is very much about the Donner Party. It shows a much less heroic image than the huge statue outside. It shows desperate people awaiting rescue. Which looks more real to you? And if I haven’t persuaded you yet, stick around.