More Than One Way to Travel (2)

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD A Great Little Museum With a Big Shameful Secret

How Long Is This Post? About 3,500 words, or 15 minutes.

Continued from More Than One Way to Travel (1)

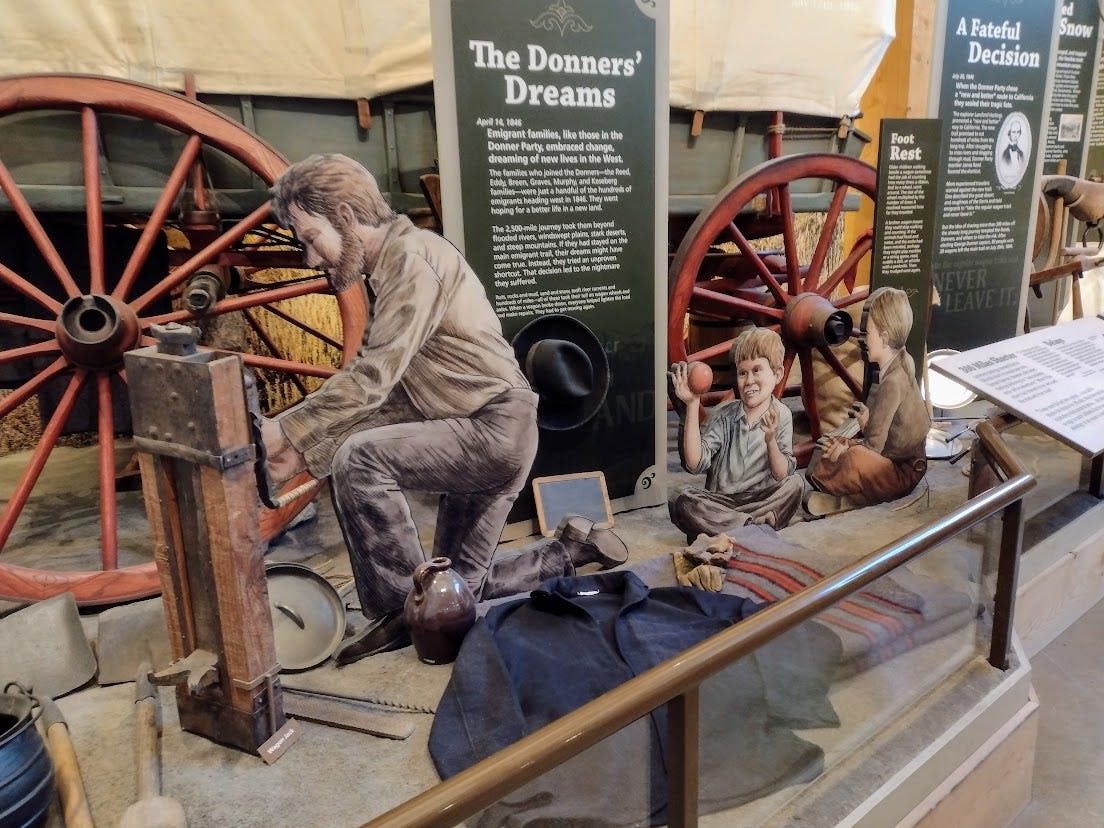

Before the photo above misleads us, know that a broken wagon wheel did not trigger the ill-fated Donner Party's 1846 journey toward cannibalism in California.

Breakdowns were normal on wagons going West. Some folks had mechanical problems so soon after leaving Independence, Missouri, their departure point for the West, that they rode their horses or mules back to the city for parts.

The farther wagon folk traveled, the more they had to rely on themselves and on companions, other travelers, federal government workers, and Indians.

Wait, what? You cry. But Laing! You must be mistaken! The West is all about personal responsibility! Rugged individualism! Just like in John Wayne movies!

Yeah, right. Let’s stop pretending: John Wayne was a Midwestern actor, a small-town pharmacist’s son, who dressed up as cowboys and soldiers so convincingly, we thought he was real.

And wagon people, who were real? They absolutely got help from fellow travelers, Indians, and federal government workers on the trail. I'll be writing about this soon.

Meanwhile, in the 21st century, when Hoosen and I drive our trusty Honda wagon through the pitiless environment of the US West, we continue to learn the hard way that exercising even a little independent judgement out here —even trusting our GPS— can get us in trouble. Ask an Eastern liberal young friend of ours who went for a little hike in the West without enough water or a clue. He ended up rescued by kind young men in Trump shirts, who offered assistance, and who wouldn’t take a stubborn “I'm good, thanks” for an answer.

Don't believe me? Consider that the Donner Party was called that name, not because they were having a good time, but because individual families didn’t dare cross America by themselves: The “Party” was a group of more than 80 people, most of them newly acquainted, trying to stay alive by helping each other. Rugged individualism? That only came in the snowbound depths of their ordeal in the Sierra Nevada mountains, when they refused to share food with each other's kids, until the food in question was each other's kids.

But until then, far from being the “I’m good, thanks” individualists we associate with some imaginary West, the Donner Party, like all wagon train folks, were eager for help. Too eager.

How Not To Be Conned

What slowed down the Donners was that they’re more like us moderns than we might guess: They were inclined to believe that celebrities know what they’re talking about, and that said celebrities are more knowledgeable than experts, especially experts who aren’t even slightly celebrities.

Lansford Hastings was a celebrity. He was charismatic, and was quick to get people's trust. Out of the goodness of his heart, after traveling West himself, he wrote a helpful guide for Americans who planned to move to the Pacific Coast: The Emigrants' Guide to Oregon and California.

Hastings even generously shared with his readers an exclusive shortcut, the Hastings Cut-Off, across the modern-day Utah desert!

His book was a bestseller, so obviously he was successful! A winner! A celebrity!

In fact, Hastings was a pointless blowhard. A self-promoter. A fraud. Lansford Hastings reminds me of Gilderoy Lockhart, the vapid and egotistical author character in Harry Potter. Which I hope helps you imagine him.

Hastings had never taken the shortcut he recommended and (of course!) had named for himself. He gave not a single rat’s patootie about wagon people. His only concern was that enough Americans moved to California to wrest the region from Mexico, and once they did that, (he hoped), they would surely elect him, Lansford Hastings, as their fearless leader.

When the Donner Party stopped by a convenience store in Nowhere, Wyoming, called “Fort Bridger”, its owner, experienced wilderness guide Jim Bridger, warned them that Hastings’s route was dangerous. He urged them to take the usual route via Idaho.

But what would he know, I’m sure they thought? Jim Bridger was some badly-dressed old bloke in a beard, selling knick-knacks with his Indian wife and his French business partner, at a ramshackle place in the godforsaken desert. He hadn’t written a bestselling book. Heck, he probably couldn’t even read.

In fact, that’s correct: Jim Bridger couldn’t read. But if the Donner Party had listened to illiterate, non-famous, unflashy, but deeply knowledgeable Jim Bridger, we would never had heard of them, and that’s a good thing. They would have likely got to California safely and in good time, and would not have ended up eating each other in snowbound hovels in the Sierras.

But that's not what happened. The Donner Party were star-struck by Lansford Hastings, and so, instead, they found out the hard way that celebrities tend to be, to use a Western expression, all hat and no cattle.

When riders (employed by Hastings) galloped up the trail to give the Donner Party a personal, printed invitation from the man himself to follow him on his route, they were utterly charmed. A real celebrity was willing to escort them, in person! Never mind that everyone the riders encountered got the exact same flyer.

The meet-up Hastings proposed never happened. Instead, Hastings-less, the Donner Party found themselves on their own, hacking out a brand new trail though the Wasatch Mountains (near modern-day Salt Lake City). That's the kind of rugged individualism nobody should ever want. That took two weeks. It then took twice as long as Hastings had claimed to cross the salt desert of modern-day Utah. Eventually, they arrived at the Sierras too late in the year to beat the snow. After that, it was all downhill to disaster.

MORAL: I don’t usually do morals at Non-Boring History. As Dr. McCoy never said on Star Trek: Dammit, Jim, I’m a doctor [of history], not a philosopher. But there is a useful moral in this story, one I'm happy to endorse. That's because, having met many celebs, and found most of them lacking in all but overblown ego, I wouldn’t trust them to guide me down my own driveway. Just saying.

Are you a celebrity or related to a celebrity? Did you find this comment offensive? Please address your complaint to the Reader Relations Gnome at Non-Boring House in Madison, Wisconsin. He will carefully read your message, before placing it in the special round file. Thank you.

Choosing Stories, Changing Times

I don’t remember visiting the museum at the Donner Memorial State Park, back in my youth, when I lived in Sacramento . But I’ll bet someone brought teenage me here, and that I don’t remember it because it sucked. How badly did it suck, you may ask? That’s the problem: I don’t remember.

So I asked a helpful staff member if she had any idea what the museum had been like forty years ago. “It wasn’t in this building,” she said, gesturing away from the high-tech, green-certified structure in which we stood. The old museum, she told me, was in the wooden building across the parking lot. She went on to describe exactly what I had imagined (or possibly remembered): Crowded artifacts (old items) like Indian baskets, terse labels with minimal and boring info, and no story told.

This kind of “cabinet of curiosities” museum was typical forty years ago. It really wasn’t an improvement over, say, the 1920s, when, if you came here to the site of the Donner Party’s horrific experience in the snowbound Sierras, all you got was a statue of a heroic-looking man with his timid wife and fearful kid. If you weren’t from California, you may never have even heard of the Donners. Even if you had, you may not have understood that this statue was supposed to represent covered wagon people in general, not the Donner Party. It certainly didn’t tell you anything about history.

Pro Tip: Statues aren’t history. What have we ever learned about the past from a basic statue, beyond “This is an important person. Worship him”?

Back in the Twenties, you would have made a polite grunt of admiration at the statue, jumped back in your Model T, and hurried on before the snow came for you, too.

The good news: This poor kind of public history is less typical than ever. Despite continued (and inexcusable) underinvestment in museums and real education in general in the past forty years, the rise of public historians has yielded some great results.

I looked around me at the museum. It’s up to date, it’s attractive, its exhibits are inviting and varied, they reflect modern scholarship, they tell great stories, and they’re easy to read. All great. Thumbs up. Little did I know in that moment that this glossy, fabulous museum, kept a terrible secret behind closed doors. [Dramatic Music]

Yeah, that’s a bit clickbaity. But at NBH, I deliver!