Where a President Lost and Won

Annette Drops By a Town That President Franklin D. Roosevelt Once Offended and Thrilled

How Long Is This Post? 6,200 words, about 30 minutes.

Annette, the Non-Boring Historian, Presents . . .

A Visit to 1938

Annette emerges from mist, actually a special effect, handpumped from a mist machine by two energetic Gnomes in Studio C at Non-Boring House. She tries to look mystical. She immediately spoils the effect by launching into a coughing fit triggered by fake mist.

TAKE TWO:

ANNETTE: Picture it . . . Sicily . . .

Annoyed Media Production Gnome yells CUT. Points out to Annette that she has somehow confused herself with Sophia from The Golden Girls.

TAKE THREE:

ANNETTE At the dawn of Non-Boring History, in long-ago Spring, 2021, only a handful of dedicated Nonnies, early visionaries and paid subscribers, were kindling the tiny flame that would one day become . . .

Media Production Gnome puts head in hands, tells Annette to get on with it.

TAKE FOUR:

ANNETTE (in a rush) So, in 2021, a couple of weeks after I started writing Non-Boring History, I knocked out this two-parter off the top of my head about what happened when Franklin Delano Roosevelt (yes, it's FDR yet again, sue me) visited a small town in Georgia called Barnesville to switch on electricity in this rural area, and then he insulted the US senator from Georgia sitting behind him, and tried to tell his audience how to vote, and then they all went bananas, and ran him out of town on a rail, although actually he was whisked away in a car, the end.

(Curtain drops with crash, stunning the Media Production Gnome, fade to black)

Hello!

So why are we talking about FDR again?

Yes, Laing, why are we? You say. This is supposed to be Non-Boring History, not the FDR Fan Club. And it's supposed to be non-partisan.

True. Nobody could accuse FDR of being non-partisan. He joked that the naval cannons outside his front door in Hyde Park were for any Republicans who came calling. But a president who could get almost all Southerners, white and black, behind him in the Thirties kind of transcends party labels.

I'm rerunning this piece from May, 2021, updated, while I'm visiting schools in Georgia, because I don’t think the original piece got the attention it should have in those early days, and it’s a great story. And also because, a few days ago, WITHOUT PLANNING, I just so happened to find myself in Barnesville, Georgia, the setting for the post. And then I’ll be reporting on my 2023 visit in an exclusive segment below, for Nonnies ( paid subscribers) only.

Let There Be Light? FDR Is In the Dark

Barnesville, Georgia, USA, August 11, 1938

It feels like a furnace on the football field at Gordon Military College in Barnesville, even by the standards of August in Middle Georgia. Fifty thousand people in the scorching sun, in a town with a normal population of 3,500. But they aren’t here for a football game. They’re here to see Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president of the United States.

Betty Smith, an 11 year old white girl, is here to help. She’s selling bottles of Coke for a nickel each, and people are buying them as fast as she can hand them out.

But Betty doesn’t miss a beat. As the President’s open top car passes her, she calls out to him, and, to her absolute joy, he waves back. She won't ever forget this, not even when she's a very old lady.

Anything he does in 1938, even speaking in a small town in Georgia, affects the entire United States. Maybe the world.

What FDR does affects Americans emotionally as well as practically. There has never been a more beloved man in the Oval Office, before or since. Two years ago, in 1936, he won a massive 87% of the Georgia vote. In Lamar County, where we are visiting today, that percentage was even higher, 92%. Now, even if we assume that some of the people voting for him were dead, in time-honored Georgia tradition, that’s still a massive landslide. If you were FDR, wouldn't you feel kingly?

Black and White Voters, Democrats and Republicans

Bear with me here. We’ll be back with Betty in Barnesville before you know it. Almost all the votes that elected FDR in Georgia in 1932, and again in 1936, were cast by white people. Very few Black Southerners in the Thirties can vote, thanks to voter suppression, such as an expensive poll tax most black people (and quite a few white people) cannot afford.

In the South, since before the Civil War, the Democrats are a white party. They are the party of segregation, of white supremacy. The handful of Black voters in Georgia are not yet willing to form any political alliance with white Georgians, even those shut out by the poll tax, and you can understand why: It’s hard to work with people who are constantly trying to humiliate you, and sometimes trying to kill you. Fair enough.

So the few Black Southerners who can vote are typically Republicans, just like 2/3rds of Black Northerners, in salute to Lincoln, and in defiance of the Democratic Party. Remember: the last Democratic President was international man of peace and enthusiastic racist Woodrow Wilson.

There is no Republican Party in Georgia in any meaningful sense in 1938. Elections are decided in the Democratic primary election, where party voters select their preferred candidate. That person then gets rubberstamped by the same voters in the general election.

Even in the primary, the tiny number of black voters are stonewalled: As of 1908, you have to be white to vote in the Georgia primary. So you can cast a Republican protest vote in the general state elections, or just not bother voting at all. But, if you are one of the very few Black citizens able to cast a vote in the South, you can vote in federal (national) elections. And you probably vote Republican. Black voters turned out nationally 2-1 for Herbert Hoover in 1932, despite his mixed record on race and his awful record in the Great Depression, but he appreciates your vote, and he does consult Black leaders.

Ahh, you know where I’m going, right? By 1938, the New Deal has changed everything, right?

No. New Deal programs segregate and discriminate, even on the rare occasions when they’re not supposed to. When FDR signs the Social Security Act in 1935, he brings dignity and peace of mind to millions of Americans. But the Act specifically excludes domestic workers and farmworkers, jobs disproportionately staffed by black people. More than half of black workers in 1935 don’t qualify for Social Security. It probably wasn’t deliberately aimed at Black people, but it has that effect anyway.

Yet, from 1936, if you’re a black voter, whether in Chicago, New York, or Atlanta you may still be a Republican for every other purpose, including congressional elections, but it's increasingly likely you voted for President Roosevelt. 76% of Black Northerners voted for FDR that year. However, 97% of black Americans lived in the South, and, like I said, very, very few could vote.

In the South, then, the Democrats in 1938 are the party of Jim Crow, of white supremacy. But not in the North. In the North, the Democratic Party is now the party of FDR.

What happened? A massive 19th century wave of European immigrants to the Northern states, of Irish, Italian, Polish, Eastern European Jews, that’s what happened. They wanted to get in on politics. They knocked at the doors of the GOP, the Republican Party. The wealthy members of the Republican Party, who feared and disdained these foreigners, switched the lights off and pretended not to be home.

So where did these new Americans go to get involved? They revived and took over the northern Democratic Party, which had been dead since before the Civil War.

So what we have now, in the Thirties, are two very different Democratic Parties, one Northern, one Southern. And in the desperate depths of the Great Depression, they all vote to elect a wealthy New Yorker to the Presidency in 1932. And even more enthusiastically, in 1936.

See, that wasn’t so hard to understand, was it? Good luck persuading Uncle Bill to listen to this at Thanksgiving!

By 1938, even black Georgians, whether they are voters or whether (more likely, thanks to voter suppression) they are not, are warming to this Democratic President, this rich white fellow from New York. If Black leaders like educator Mary McLeod Bethune, a friend of Mrs. Roosevelt, can support FDR, this is a good sign. Not that black people are completely convinced.

Thanks to the influence of black members of the FDR administration led by Mrs. Bethune, and white liberal members of the administration like Harold Ickes, access to the New Deal is improving, somewhat, for black people. President FDR is now someone on whom most black and white Americans, black and white Georgians, can agree. That is little short of à miracle in 1938.

But the New Deal? It gets mixed reviews from black Georgians. Not all white supporters of FDR are unreservedly enthusiastic about the New Deal, either. Less than a hundred miles south of Barnesville, lives a white farmer and small-town grocer named James Earl Carter, Sr. One day, he will be overshadowed by his better-known Jr., President Jimmy. Carter, Sr. votes for FDR, of course. But he’s a conservative, unlike his unusually outspoken and liberal wife, and he is not entirely happy with the New Deal. Washington bureaucrats tell him and his neighbors to plough under perfectly good crops to push up too-low prices.

Little White House, Warm Springs, maybe 1938.

The aroma of pork chops, turnip greens, and cornbread floats through the house from the little galley kitchen. Daisy Bonner is making dinner on the fancy electric stove. When the President is back in Washington, or New York, Ms. Bonner floats among other white people’s houses for employment, cooking delicious meals for too little money.

FDR looks again at his electric bill for the cottage, his retreat near Warm Springs, Georgia, which everyone now calls the Little White House. He first visited Warm Springs in 1924, to bathe in the healing waters, hoping for a miracle, to regain the use of his legs. By the time he left, he had bought the resort. He built this little retreat on nearby Pine Mountain, and moved in, in 1932.

Not for the first time, FDR marvels at the absurd figures on his Georgia Power electric bill. He can afford it, of course. But he knows his neighbors can't.

Suppose electricity was cheaper? Farmers could have light in their homes. No more stinking and dangerous kerosene lamps. Perhaps in time, modern electricity, not smoky wood fires, will power the cooking stoves of ordinary rural Georgians . . . ordinary rural Americans. What a relief that would be to women on farms in California, Iowa, Georgia, his own home state of New York, women ground down by the everyday drudgery of their lives.

There are other advantages.

Maybe if rural Georgians could hear the radio, maybe if the world opened up to them, they might start to desire and support more education, more progress, more joy, less hate for their colored neighbors. They might read books in the evenings, using light from electric lamps.

And they could listen to the President’s Fireside Chat broadcasts, and trust him as people did in the cities, from Atlanta to San Francisco, as the fatherly friend who sometimes visits their homes for a pleasant and interesting discussion.

FDR wants the New Deal to pivot. Putting people back to work was just the first step. Now he wants to improve their lives, so that you don’t need to be a child of wealth and privilege to have a happy existence. Art, music, theatre, recreation grounds . . . on and on, these are all part of the New Deal’s new agenda.

And so is bringing electricity to every American home. This is the beginning of the golden age of the common people, and stamped all over it is the name of a rich man who, behind the scenes, gets around in a wheelchair: Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Trouble is, if we’re reading FDR’s mind in 1938, his New Deal for Americans is in serious danger of fizzling out. Because the Supreme Court is in the way, and the justices keep striking down his programs as unconstitutional. Because a few powerful white Southern leaders are desperately trying to hang onto an identity of self-reliance that doesn’t mesh well with their people’s cheerful acceptance of millions of dollars in federal aid via FDR’s hugely popular New Deal programs. Because these same white Southern Democrat politicians ride his popularity to victory in Congress, only to vote against New Deal programs they don’t like. Politicians like Senator Walter George of Georgia. In fact, Sen. George is the worst: A pleasant fellow, but the biggest thorn in FDR’s side when it comes to the New Deal. Senator Walter George, as it happens, will also be at today’s event on the football field in Barnesville. And he’s in for quite the surprise.

FDR is a “Yankee” as white Georgians say. But he’s also an honorary Georgian. He loves his neighbors in Warm Springs. They love him. He knows them. They know him. He wants and needs their help today, to help him to help them, and he knows that the people in Barnesville and Lamar County will back him to the hilt. 92% of them voted for him in 1936, and today should convince the remaining holdouts, that 8% who did not.

Even more important, they’re going to help him purge the Democratic Party in Congress of these Democrats in Name Only, these relics getting in the way of the New Deal and a liberal, national Democratic Party. Relics like Senator Walter George.

And so it’s with every confidence that FDR, on August 11, 1938, knots his tie before the mirror, before wheeling himself to the door, where the open-top car and his entourage of aides and Secret Service men are waiting.

The President is completely in the dark.

Look, I’m not psychic. Until now, this section has depended on conjecture, imaginative recreation, and my imperfect grasp of FDR’s thinking. I believe I’m not far wrong.

Soon, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is on his way by car along Georgia's dirt roads, from his second home at Warm Springs, to little Barnesville, in the middle of (checks map) nowhere. He is bringing something even more amazing than jobs. He is bringing light. Literally. He is on his way to bring electricity to Lamar County. People are pouring in from the surrounding countryside to witness this historic event: Electricity is thrilling, and so is the arrival of their President. Both at the same time? This is going to be one of the most memorable days of their lives.

Grover on the Football Field

Grover Worsham is fascinated by the sight of pop-up shops, as we would call them today, a whole line of tents pitched on the ridge overlooking the field, merchants hawking goods from within their canvas walls. They're selling small appliances for the home, products like toasters, hair curlers, lamps, irons, and of course, radios. At this moment in Barnesville and surrounding Lamar County, these neat toys are completely useless without electricity.

But a miracle will happen today. By the time President Roosevelt leaves town, everyone in Barnesville, and the whole of Lamar County, will be able to plug in their new toys, in the comfort of their own homes, and switch them on, and use them. When President Roosevelt finishes his boring speech, you see, he will press a red button, and, Grover has been told, magic will follow. Grover cannot even imagine it.

Grover, who is just eight years old, is excited.

Electricity will surge through the newly-installed wires at Grover's house. It will come all the way from Tennessee, where it’s generated by water falling from mountains. It will travel faster than anyone can imagine along wires strung on poles through Georgia. It will arrive in his home along a last few miles of wires put up by federal workers with the help of proud Lamar County farmers, men he knows, working together with each other, and with the federal government. All of this will bring Grover's family into the 20th century.

Grover may not know about this next thing, though: Georgia Power isn’t pleased to have competition. Sometimes the farmers’ wires are mysteriously cut. The farmers fix them. There’s too much riding on this to accept sabotage, give up, and go home to their dark, lamp-lit homes.

Bringing electricity involves unlikely partnerships. The Rural Electrification Administration (REA), one of the many, many programs of FDR’s New Deal in far-off Washington DC, has made this possible. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), another New Deal program, has made this possible. And conservative, church-going white men of Barnesville and Lamar County, almost all committed to the firm belief that Black people are inherently inferior to them, have made this possible.

Hmm. Doesn’t this all sound a bit, I don’t know, strangely socialist to you? In Georgia?

Betty, the President, and the Crowd

On the football field of Gordon Military College in Barnesville, 50,000 people, apparently an all-white crowd, are listening to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Where are Barnesville’s Black citizens today? I don’t know. They're not in surviving photos of the crowds. Likely, they had been made aware that their presence wasn’t welcomed by the powers-that-be.

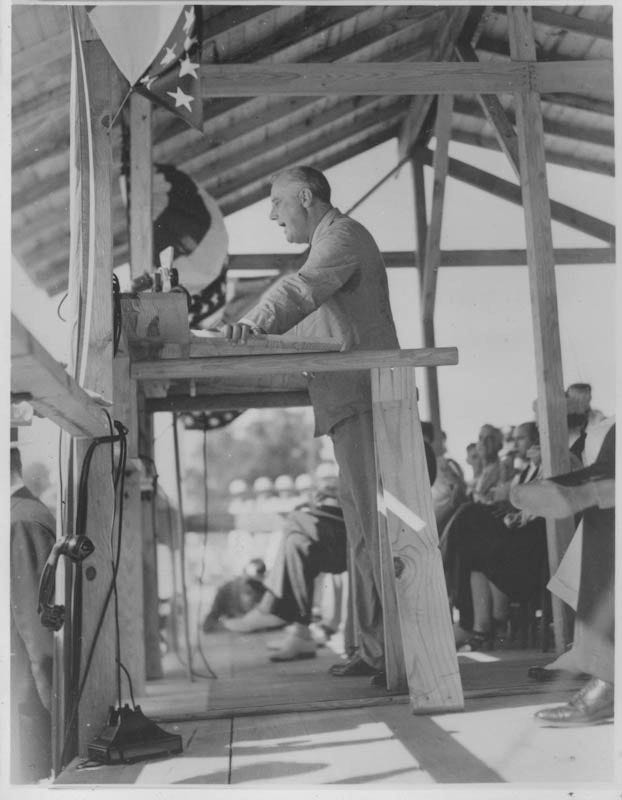

The President, although dressed in a tan suit, is dripping with sweat in the heat. As usual, he’s gripping the podium to stay upright. He does this to disguise the fact that he cannot walk, whether due to polio or, as medical historians have recently suggested, Guillain-Barré syndrome. He is speaking into a forest of radio mics from local stations like WAGA in Atlanta, and national networks like CBS and NBC, as well as the microphone that amplifies his words to the excited crowds standing on the football field in front of him.

Among them are Grover Worsham (age 8) and Betty Smith (11), neither of whom understands much of the speech, but who are both excited to be in his presence just the same. Everyone is just as excited about the purpose of the President's visit: to bring electricity to ordinary people’s homes for the first time. All is ready, thanks to Roosevelt, his New Deal programs, and, especially, the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) in Washington, which worked with local people to make this day possible.

Sitting behind the President on the covered stage? The Very Important People: The Governor of Georgia, US Senator Walter George and his junior, Senator Richard B. Russell, US Attorney Lawrence Camp of Georgia, maybe a couple of dozen more dignitaries. Hovering around, Secret Service guys in trilbies and straw hats, and newspaper reporters, including the guy from the New York Times.

Betty Smith, 11, is still standing at her now-empty soda cooler. She is close enough to the President to hear him speaking through the echoing microphone. She tries to listen to him, although she doesn’t really understand what he’s talking about. The Gordon Military College football field on which she and the crowd are standing, on which the platform on which the president is speaking stands, was transformed in her short lifetime. She remembers how it was a swamp and a steep gully. It was transformed into a wonderful football field by young Georgian men hired by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), another New Deal program.

The speech is going well. The crowds are in good spirits, and cheering.

But suddenly, the cheers aren't as loud as they were a moment ago. The crowd is more subdued. And then Betty hears the last thing she could have expected to hear today. Boos. People are booing President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

That can't be right. Can it? Betty is confused. And so are we.

Boos come from the crowd, and they are directed at the most popular president in American history, a man who, until a few minutes ago, had the crowd in the palm of his hand.

Why would anyone boo President Roosevelt? And today of all days?

We know about the booing because, in 2009, 83 year old Betty Smith Crawford of Barnesville reminisced to an Associated Press reporter about that day when she was eleven years old, and sold out of Cokes, and President Roosevelt came to Barnesville: “One thing I remember was that they would cheer and cheer and cheer,” she said. “All of a sudden, there were boos.”

In 1938, Felix Belair, Jr, the New York Times reporter who is present, talks about the controversy, but doesn’t mention actual booing of the President. But then there are a lot of things the New York Times and other reporters don’t mention about the President in 1938: The wheelchair. The girlfriends. So maybe this is one of those things.

Did Miss Betty’s memory fail her in old age? Whose doesn’t? But what she said next is verified beyond any doubt: President Roosevelt lost the crowd’s goodwill “ . . . after he asked people to vote for Mr. Camp.”

What on earth just happened? This time, I’m sure I know that’s exactly what FDR is thinking.

On The Honorable Gentleman from Georgia and the Yankee President

U.S. Senator Walter George of Georgia is a Democrat, because of course he is in Georgia in 1938. More surprisingly, he is a “moderate” on race. This means he’s not a closet Klansman. It does not mean that he voted for anti-lynching legislation in the 1920s, because he didn’t.

He didn’t vote for FDR in 1932, either, and even now, he doesn’t care one bit for this New Deal. Oh, the poor people of Georgia love free money from Washington. He understands that all too well: His parents were dirt-poor sharecroppers.

But Senator George is no longer poor. He lives very differently now, of course. And he thinks very differently now.

Senator Walter George does not think it’s the role of the federal government to give handouts or hands up.

Last year, the President tried to get around the Supreme Court, which opposed his New Deal programs to improve life for Americans, as he presented it. He tried to get Congress to agree to allow him to pack the court, to appoint additional judges to end the roadblock. Sen. George definitely didn’t support that. Not at all. The court-packing scheme failed, and with it, the chances for a massive shift in Americans’ standard of living, and their relationship with the federal government.

Let’s rewind again. Here’s FDR standing on the podium, at the lectern. Behind him, the important people, including Senator Walter George, and Lawrence Camp, the former Georgia Attorney General. Camp is now US Attorney, and he’s running against Senator George this year in the Democratic primary. The primary in Georgia might as well be the general election: Apart from the handful of black people who can afford the poll tax, there are few Republicans in Georgia. And anyway, you have to be white to vote in the Georgia primary.

So What Just Happened? FDR’s Speech So Far . . .

The President has reminded everyone that federal government funds from Washington will soon bring new roads to Barnesville:

I am glad to come back to Barnesville and the next time I come to Georgia I hope you will have a good road between here and Warm Springs.

He has flattered Senator Richard B. Russell, who turned against the New Deal once in office, but is not up for election anytime soon, so he might as well make nice to the fellow:

Today is the first time that I learned that Dick Russell came here to college and I must say that it must be a pretty good college.

He has flattered ordinary Georgians and their fair state:

Fourteen years ago a Democratic Yankee, a comparatively young man, came to a neighboring county in the State of Georgia, came in search of a pool of warm water wherein he might swim his way back to health, and he found it. The place -- Warm Springs -- was at that time a rather dilapidated small summer resort. But his new neighbors there extended to him the hand of genuine hospitality, welcomed him to their firesides and made him feel so much at home that he built himself a house, bought himself a farm and has been coming back ever since. (Applause) Yes, he proposes to keep to that good custom. I intend (to keep on) coming back very often. (Applause)

FDR is on a roll now, talking in that rich, resonant voice to his adoring public. Betty Smith Crawford remembered: “He was a dynamic person. If 10- , 12- 13 -year-old kids are interested, you know it’s something special. . . He had charm oozing out of his pores.”

Now he goes all out. He flatters Georgians that they and their state are responsible not only for bringing electricity to Lamar County, but to the entire nation:

In those days, there was only one discordant note in that first stay of mine at Warm Springs: When the first of the month bill came in for electric light (for) my little cottage I found that the charge was eighteen centers (per) kilowatt hour -- about four times as much as I (paid in) was paying in another community, Hyde Park, New York. And that light bill started my long study of proper public utility charges for electric current, (and) started in my mind the whole subject of getting electricity into farm homes throughout the United States. And so, my friends, it can be said with a good deal of truth that a little cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia, was the birthplace of the Rural Electrification Administration.

As the crowd applauds, he finishes on an upbeat note:

The dedication of this Rural Electrification Administration project in Georgia today is a symbol of the progress we are making -- and, my friends, we are not going to stop. (Applause)

And soon the crowd stirs expectantly, thinking that FDR will push the red button and turn on the lights. Instead, the President changes the subject.

And this is when things go pearshaped (Britspeak for horribly wrong)

FDR starts out promisingly, addressing respected Democratic US Senator and New Deal opponent Walter George, who is sitting right behind him:

. . . Now, my friends, what I am about to say will be no news, no startling news to my old friend—and I say it with the utmost sincerity—Senator Walter George. It will be no surprise to him because I have recently had personal correspondence with him and, as a result of it, he fully knows what my views are.

Let me make it clear—let me make something very clear- that he is, and I hope always will be, my personal friend. He is beyond question, beyond any possible question, a gentleman and a scholar (applause)

Okay, this is starting to sound like something from Shakespeare. It sounds, in fact, a whole lot like Mark Antony’s speech in Julius Caesar, in which Antony flatters Brutus, lead murderer of the title character, when he is, in fact, rhetorically stabbing him in the back, just as Brutus himself had betrayed his friend Caesar.

Astute listeners in Barnesville, probably the very few who know their Shakespeare, are realizing that FDR is about to put the knife in. He builds up to the moment. He goes on and on about his friendships with politicians, especially Senator George, men who oppose him, but are still his friends. Then he reminds them that the New Deal, and all its goodies, depends on the firm support of his friends in Congress, even if they quibble over details.

And now the President does it. He goes there.

(D)oes the candidate really, in his heart, deep down in his heart, believe in those objectives? And I regret that in the case of my friend, Senator George, I cannot honestly answer either of these questions in the affirmative.

As for the other two candidates? FDR dismisses out of hand the rabidly racist former Governor, Eugene Talmadge. Instead, he pumps up candidate Lawrence Camp, sitting with him on the stage, and probably both thrilled and embarrassed. And then, in case anyone had missed his point, FDR drives it home with a sledgehammer:

I have no hesitation in saying that if I were able to vote in the September primaries in this State, I most assuredly would cast my ballot for Lawrence Camp.

In 2009, Betty Smith Crawford remembered: “People were saying, “Nobody’s telling me how to vote, They booed and left.”

That’s probably an exaggeration: Plenty of supporters seem to have continued to cheer and applaud. But still.

The speech is over. The President forgot to say “Let there be light!” which was in his script. For whatever reason, he never pushes the button to light up the county. That happens without presidential help. After some awkward conversations, including with Senator George, FDR gets back in the car, and is driven away.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt has forgotten the first rule of being a Yankee in or outside Georgia: Don’t criticize or tell white Georgians what to do, even if you evidently mean well, and what you’re suggesting is clearly in their own best interests. Don't underestimate white people’s capacity for taking offense, of cutting off noses to spite faces. That's what matters in Georgia, are you a native, not whether you have invested time and money, heart and soul, in the state. FDR is not a native. He never will be.

A hundred miles away, James Earl Carter, Sr. soon reads about what happened in Barnesville. He resents it. He doubles down in his determination to vote for Senator Walter George.

A month later, on September 14, 1938, Lawrence Camp, running for US Senate for Georgia, came third with less than 23% of the vote. Eugene Talmadge came second, with 32 % of the vote. With 141,235 votes, almost 44%, all cast by white people according to state law, Sen. Walter George won. The result would not be final until the general election in November, but in a one-party state, it was already a done deal.

With Sen. Walter George’s victory in November, and those of other conservative Democrats and Republicans elsewhere, because it wasn’t just what happened in Barnesville that affected the elections, large parts of FDR’s hopes for the New Deal were put on ice. We’ll never know what Americans missed, although the wartime Second Bill of Rights gives us an idea: good healthcare, good housing, good education, a fair market for farmers.

To be honest, it sounds like my childhood in postwar England. But things in America in 1938 took an altogether different turn.

The fate of the New Deal is a moot point right now in 1938. Regardless of what happens in Barnesville or Washington, FDR’s attention is increasingly drawn thousands of miles away. In September, 1938, at the same time as Walter George wins Georgia's white primary, Europe comes to the brink of war, averted only when British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain hops a plane to Germany and negotiates an agreement with German dictator Adolf Hitler that Chamberlain claims promises “peace in our time.” We all know how well that works out.

The following month, on November 9, 1938, the night after the general election confirmed that Sen. Walter George will remain senior US Senator for Georgia, Nazis in Germany attack Jewish people, and their homes and businesses, in a horrifying night of terror that will become known as Kristallnacht, or “Night of Broken Glass”. War is coming, and it will end the Depression decisively, and at unimaginable human cost.

Unaware of what faraway events will mean for them, of the descent into darkness, the people of Lamar County, Georgia, marvel at their changed lives. They have electricity, now and ever more.

Let there be light.

Aftermath

Surely, eventually, Georgia Power will concede the rural areas of the state to these electric membership cooperatives, as they’re called, these non-profit associations of farmers and other rural people? Then rural Georgians can, at last, enjoy electricity, right?

No, of course not. In the 1950s, and long after, Georgia Power is still fighting non-profit Electric Membership Cooperatives (or, as Georgia Power and its allies called them, “phantom socialists”. )

If you live in rural Georgia, next time you pay your electric bill, you may find yourself pausing, and looking at who you are paying for your electricity: Excelsior Electric Membership Cooperation, Coastal Electric. Snapping Shoals EMC. Southern Rivers Energy. Dozens of them, even though a few now use names that hide their New Deal origins. All of them are member-owned and directed co-ops that serve ten million rural Georgians, across 73% of Georgia’s land area.

And all are supplied with electricity by the “phantom socialism” of FDR’s New Deal.

Oh. Wait. Not so fast.

Georgia Power won the war in the courts in the 70s. Long story, bottom line: They now control the supply. But if you live in rural Georgia, you own your local electric company, unlike your local hospital that closed two or five years ago. And so long as that’s true, I guess, you can continue to keep the lights on.

Nonnies (paid subscribers) can read both parts of the original two-part post. They also enjoy exclusive access to this Behind the Scenes post.

February 9, 2023: Following FDR to Barnesville, Finally

It's been 85 years since FDR put Barnesville, Georgia, on the map. A lot has come and gone since then, including me. But in 23 years of living in Georgia, I never stopped by Barnesville. On the road this week, I suddenly realized I would be passing the town, and, even though I had too little time, I stopped by. I want to show you what I found.