When Enemies Become Us

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD A successful colonial rebellion in America (no, not that one). A Civil War battle in an unexpected place. And a British movie star who left Hollywood for good.

This is an Annette on the Road post at Non-Boring History, in which historian Dr. Annette Laing writes about her travels in tourist mode, learning and sharing as she goes. For a guaranteed place on the mailing list, access to all of Annette’s posts, audio voiceovers on many posts, the chance to get postcards and other fun mail from Annette, online talks and meet-ups, the opportunity to comment, plus so much more—and most especially because there’s never been a better time to support a real historian writing engagingly and enthusiastically about history for the public—become a Nonnie, an annual or monthly subscriber to Non-Boring History. It’s cheap: If you don’t hesitate to buy a coffee or beer once a month, then don’t hesitate to support. Details:

New? Learn what Non-Boring History is, more about Annette, and why they’re both unique:

Note from Annette

A place where a successful colonial American rebellion happened in which Brits weren’t the baddies? Ooh, yes!

Ironically, there is one Brit in this story, and she’s a goodie! No, she’s not me.

And when goodies and baddies join forces and became each other, well . . . How interesting is that?

Oh, and this same deserty place hosted a Civil War battle, unlikely though that sounds!

Ooh, and rattlesnakes! This post has it all!

So let’s start from the start, shall we? Time to join Annette and her long-suffering spouse Hoosen on the road in New Mexico (a US state that long ago tired of other Americans assuming it wasn’t part of the US. It is. It also has the best architecture, and a fascinating obsession with chile peppers.)

Oh, and, as ever, a map helps with this post. Overcome your pride and let’s all admit our geography could be better (mine certainly could). Pull up a map of the southwest US, New Mexico to be exact. It’s worth your time. Yes, Brits, you too. In fact, especially you.

Note to Nonnies (paying subscribers): I bought far too many postcards on this trip, so don’t be surprised to get one in the coming weeks! :) If you’re not signed up for GiftMail, a free extra as a mark of my gratitude to my supporters, please hit reply. If you’re not a paying subscriber, this is another reason to become one! A.

Doubletake

“There was a Civil War battle here,” Hoosen said. “The battle of Glorieta Pass.” I thought he’d lost his mind. I freely admit I’m not a Civil War buff, but neither is Hoosen. How could an American Civil War battle have been held in the Western desert? But sure enough, here was a historical marker!

I mean, you just don’t expect this in a mountain semi-desert, do you?

So here’s the deal: Glorieta Pass is a break in the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) mountains, the most southerly range of the sprawling Rocky Mountains. The Rockies form the spine of the US, and they may even determine what your mayonnaise is called.* Glorieta Pass, traveled for millennia for settlement, exploration, and trade, happens to be the venue of the most western battle of the US Civil War.

*Seriously. The most popular brand of mayo in the US is called Best Foods west of the Rockies, and Hellmann’s in the east. No, I don’t know why. No, neither of these names is either descriptive or appealing. Yes, this has fascinated me ever since I arrived in this country.

I shouldn’t be surprised that the Civil War Confederacy (the South) saw the West as a goldmine of profitable natural resources (including gold), all of which awaited exploitation. Despite its romantic reputation, the US West was always to many a place to get rich on natural resources, starting with land, and preferably as a free gift from the federal government. The South, meanwhile, was long a place where getting rich from other people’s efforts was the fond ambition of many if not most people. Yes, I know that both West and South are more complicated than that, but it’s hard to ignore elephants on the sofa. Put South and West together, and here's what you get.

The Confederacy, led in the West by a dude named Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, eyed the riches of the far West: Gold in Colorado (Yes, in Colorado: The California Gold Rush was old news by the early 1860s). Minerals in Nevada. Ports for international trade in California. And even the northernmost states of Mexico, which were rich in profitable mineral goodies, from gold to salt.

Brig. Gen. Sibley recruited troops in Texas. They captured the small city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, on March 10, 1862. It didn’t take long before Union troops, mostly volunteers from Colorado, arrived and kicked Confederate butt in two days of fighting, then burned down the Texans’ camp full of supplies, and let loose all their horses.

This, the battle of Glorieta Pass —in breathtaking overstatement—is often called the “Gettysburg of the West”. Um, what?

Yes, both were Confederate defeats, but Gettysburg resulted in up to 51,000 casualties, while Glorieta . . . didn’t. About 147 were killed or wounded.

Still. Both battles were turning points: Gettysburg, in 1863, was the beginning of the end of the Civil War. Glorieta Pass saw the Confederates turn and flee back to Texas, ending the West’s role in the Civil War.

How about that.

But we hadn’t come all this way for an unlikely Civil War battle, curious though that was.

We had come for nearby Pecos National Historical Park, and all its fascinating associations.

Finding Pecos

If the American Civil War floats your boat, you may be keen to know that the overworked Park Rangers at Pecos National Historical Park offer a guided walk on that very theme. Indeed, as we arrived, we found a cheerful ranger standing by, outside the visitor center, ready to lead a group that was rapidly forming. He was a Southerner, originally from North Carolina, so was appropriately enthusiastic about Civil War thingies.

I could have taken that walk, and learned a whole lot more about the Battle of Glorieta Pass. As you may know, however, I’m pretty much Civil Warred Out, having lived in Georgia 24 years. To be honest, it’s a rare military historian (only one, in fact, the amazing Dr. Carol Reardon) who can interest me in Civil War battles. Hoosen is of the same mind, despite his unexpected Civil War knowledge. So we politely declined this opportunity, and instead started in the fabulous visitor center by getting up to speed with this site.

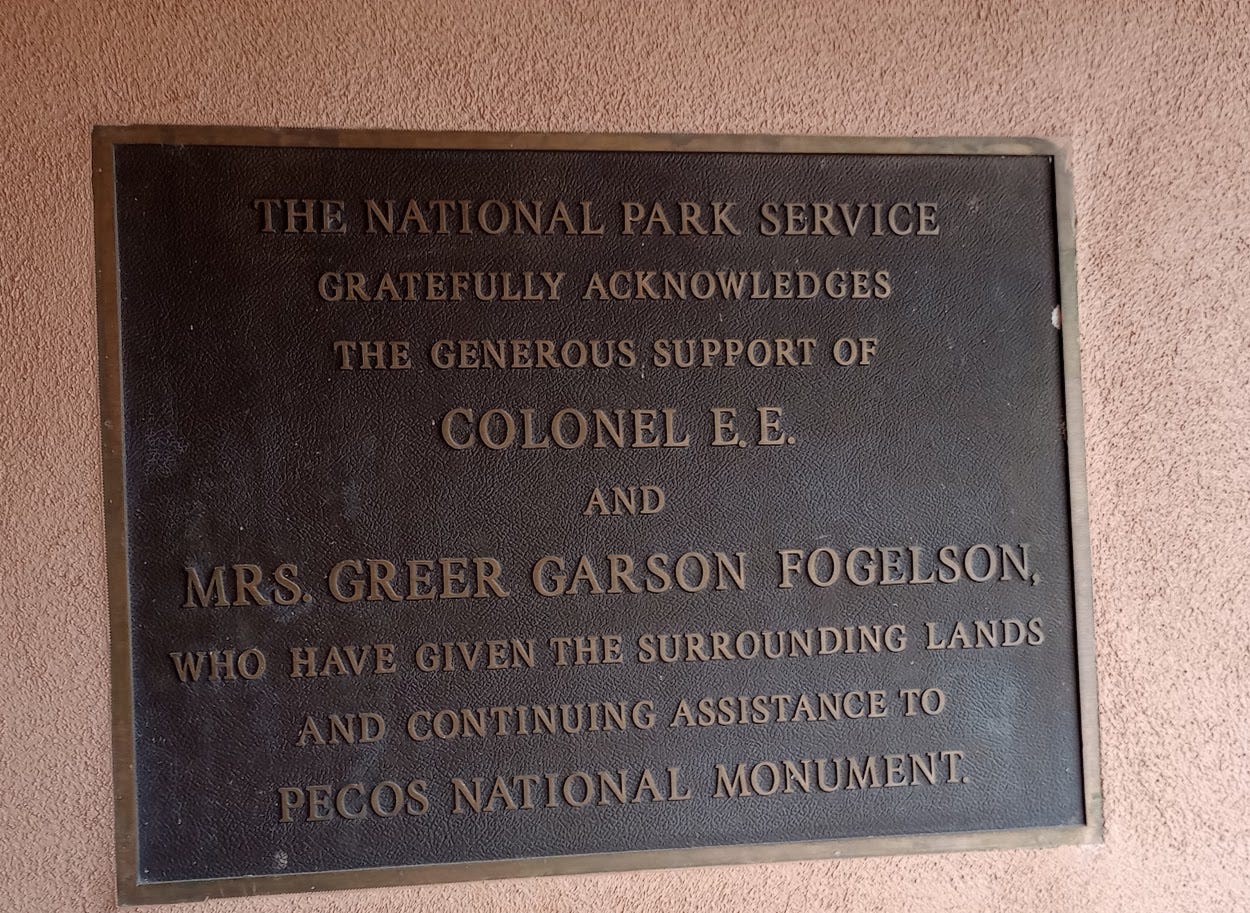

The visitor center, we were astonished to learn, was built by a Brit and her American husband. They also donated much of the surrounding land.

And that Brit donor was not just any Brit. The name Greer Garson may or may not ring a bell for you, but I can assure you that, while I’m too young to know this, she was a Big Deal in Hollywood in her time. British film buffs may recall Garson in Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939 version, not the one with Peter O’Toole and Petula Clark). Americans may know Greer Garson as the star of Mrs. Miniver (1942) a wartime propaganda film aimed at building American sympathy for the Blitzed Brits. Despite Mrs. Miniver’s home looking more Hollywood than Cricklewood, the cast (most of them expat Brits dusting off their accents) did their darndest. Americans couldn’t tell the difference, and cried their eyes out, so aim achieved.

Eileen Evelyn Greer Garson (1904-1996) was not just a pretty face: She was stunningly well-educated for a British woman of her generation. She held a degree in French and 18th century literature from the University of London, plus she did postgraduate work at France’s University of Grenoble.

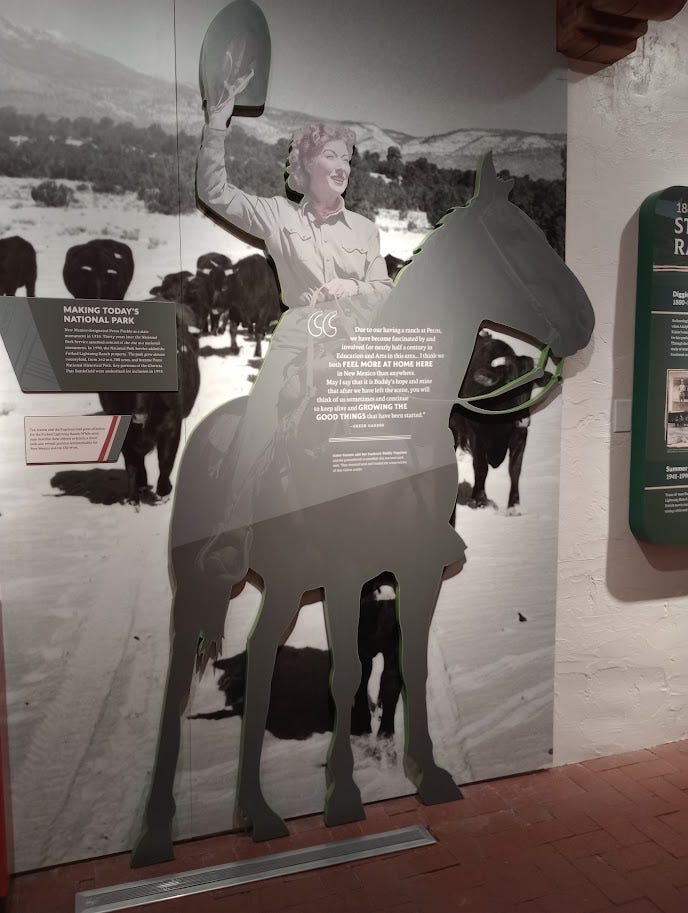

But clearly, Greer Garson also had a wild Western side, as shown in the photo below. After her successful Hollywood career, she and her third husband, American E.E. “Buddy'“ Fogelson (lawyer, oil man, and US Army Colonel on General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s staff during WWII) retired to their ranch in New Mexico.

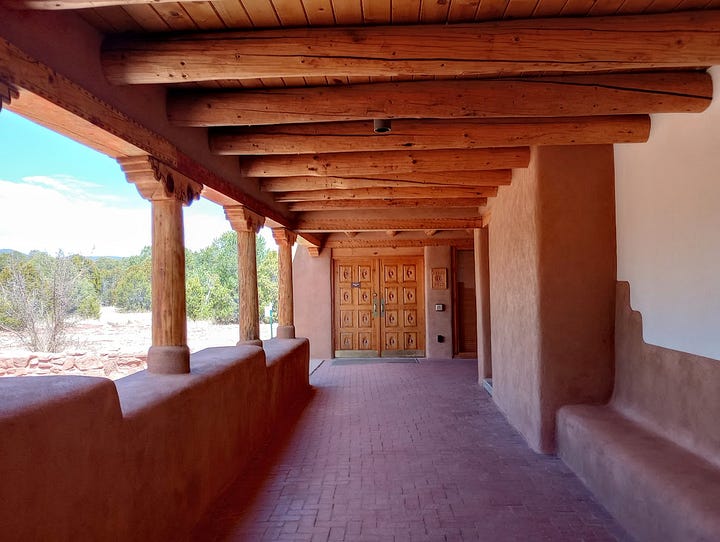

Garson and Fogelson later donated (or sold for cheap?) their ranch to a local conservancy. This land, in time, formed the basis for Pecos National Historical Park. The couple also funded the gorgeous visitor center, with its beautiful southwestern architecture:

It was through the outdoor corridor above that we made our way to a beautiful trail leading to an astonishing past. As we go, I’ll work in what we learned from the visitor center museum.

Oh, but first, we had a warning:

They weren’t kidding, either.

All Change at Pecos

Thanks to how American Indians have been portrayed in fiction and drama (ghastly), many of us get the impression that they are backward people who live in an unchanging past. Nothing could be farther from the truth, and history is all about how change is constant, including in Indigenous societies around the world. The story of Pecos brings that home.

People were here, in this place we call Pecos, long, long before they settled down. They were hunter-gatherers: They lived from the land but kept moving on. But, and this is important, they didn’t wander aimlessly without destination or purpose, hoping to get lucky when a mammoth wandered by. Hunter-gatherers deliberately followed a seasonal path to the best places for animal protein and plant foods. As someone who loves seasons of all kinds, that sounds rather appealing, although I’m also betting it was harder than it sounds. It got harder when the Ice Age ended, and the mammoths went away, so that people had to content themselves with hunting smaller mammals.

The hunter-gatherer way of life began in Pecos around 11,500 BC, and although people left little trace, a five thousand year old dart point carved from quartz is among the rare precious evidence of their presence. Oddly, it was around roughly the same time that dart was made, and after thousands of years of traveling in search of food, that people decided they would rather not move around so much.

I don’t know about you, but when I read “hunter-gatherers” or “shift to agriculture” , my eyes glaze over. This is such a familiar story in human history.

But what got my attention at Pecos was reading that this was not a sudden change from hunting/gathering to farming, as I —and maybe you—have tended to imagine.

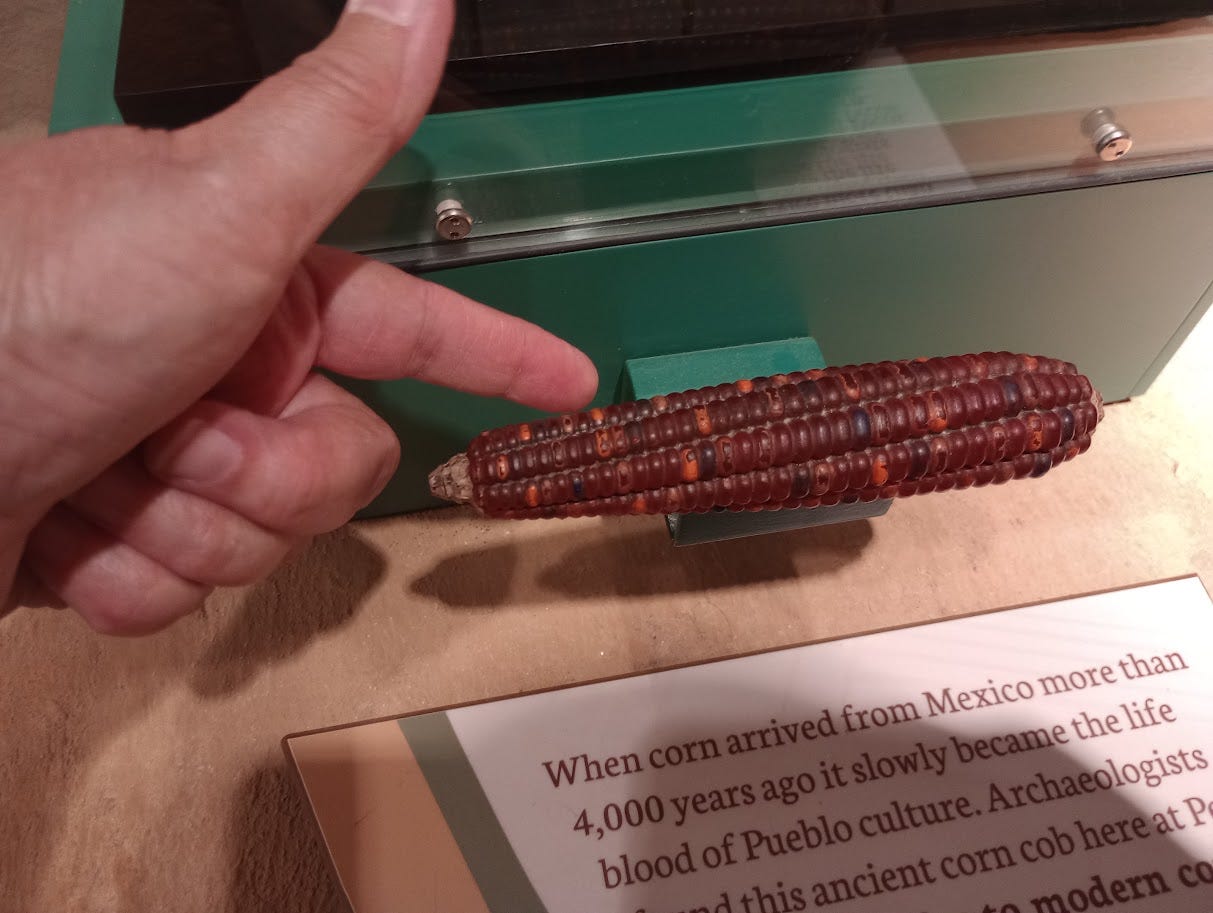

Even as people continued to migrate seasonally around the region in search of meat and plants, they started deliberately planting corn and then coming back to harvest it. This clearly proved a success, as they added crops of squash and beans. The more interest they took in these three staples, the more care and time they spent cultivating them to make them bigger and more productive, the longer people stayed put. Clearly, this was a gradual transition from hunter/gatherer to farmer.

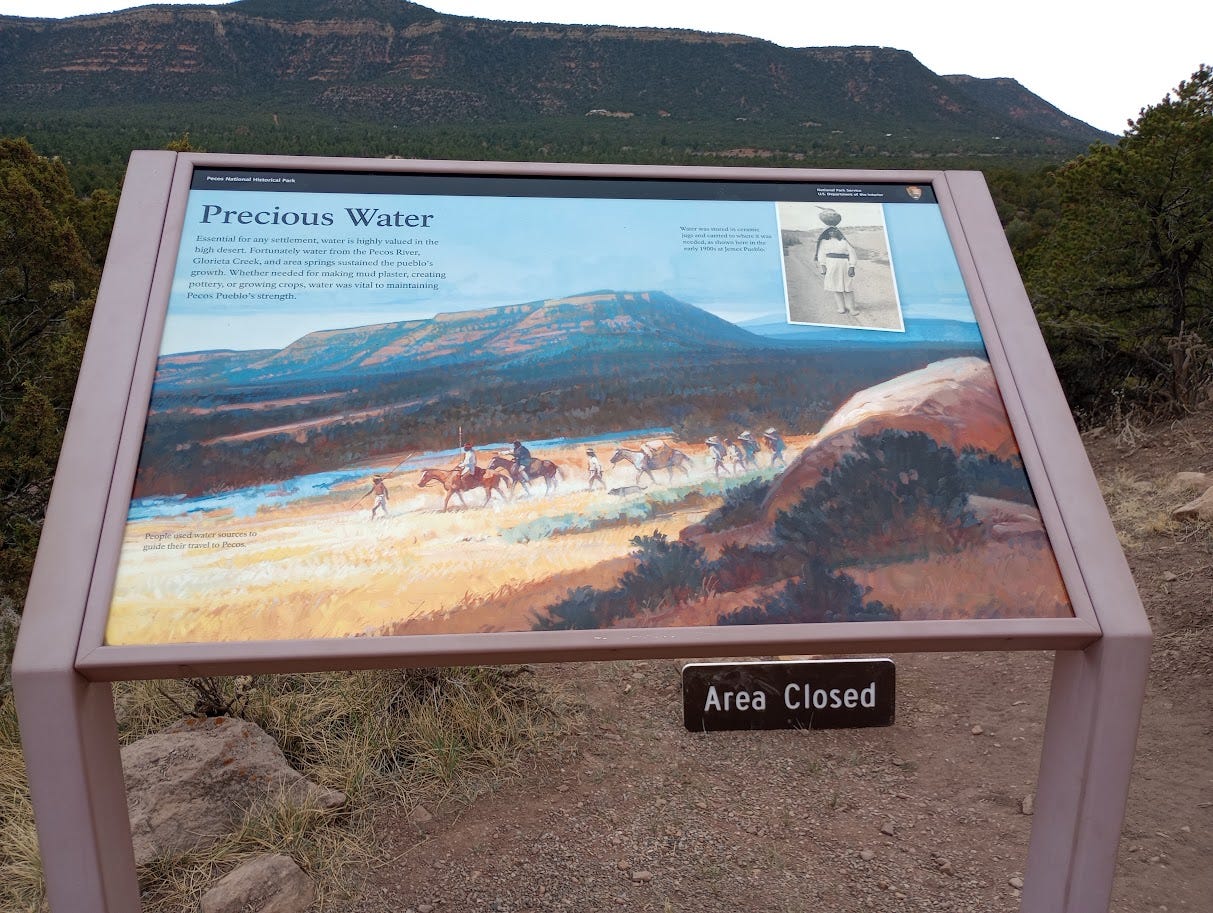

By 800 AD, a village was established at Pecos, on a high point close to Glorieta Pass. Here was good sandy soil for farming. From their elevated ridge, the people could see the approach of strangers. Most importantly, even water was available from creeks and rivers, not only for drinking, but making adobe (clay bricks) for building.

Rainfall, however, remained scarce and spotty. So people at Pecos planted fields all over their lands as insurance against failure. They also bred crops to be as productive as possible, especially the staples of corn, beans, and squash.

As crop yields got better and better, and the community became more settled, more and more people could be supported, and Pecos grew. The community now found themselves with surplus harvests and plenty of people, both of which needed permanent housing.

The first permanent dwellings and storage places here, around 800 or 900 AD, were pithouses, structures that were partly underground, and accessed by a ladder from the roof.

I thought of the very similar semi-underground Iron Age house I have seen in Scotland.

Around this time, Pecos people also began making pottery in which to store food, and cook it.

By 1250, people at Pecos were building housing above ground, and prettying up their pottery, like this:

Sometime between 1325 and 1525, Pecos began buying most of its pottery from traders who arrived via what the Spanish would later dub the Glorieta Pass. Don’t look so shocked, unless you live off-grid and make everything you need for yourself which, let’s be honest, you don’t. It’s all cheap stuff from China these days! For now! That said, Pecos artisans moved into making extra-fancy luxury pottery for trade, and for which Pecos became known.

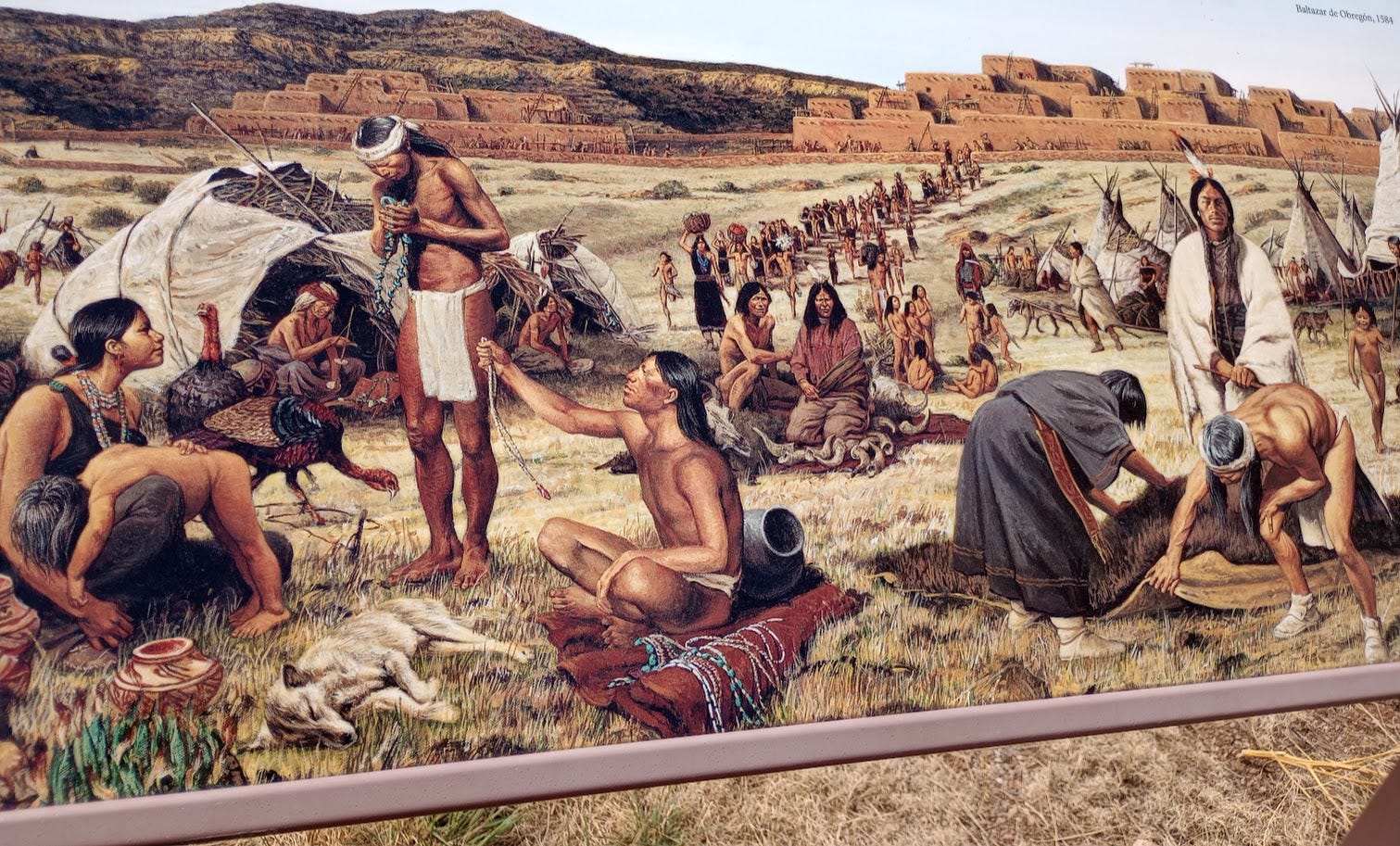

From its great vantage point in the Glorieta Pass, Pecos was ideally placed to become a major center for traders from as far away as Mexico’s coast (which supplied exotic shells and feathers for decoration) and across the Great Plains. Pecos was the site of trade fairs in which the people of Pecos could sell what they had in abundance, especially fancy pottery and corn, and buy what they did not, like buffalo (whose range did not extend into mountains).

Traders included those bringing goods like attractive shells from Mexico and nomadic hunter/gatherer peoples from the Plains , particularly the Apache, who set up their tents (tepees) outside Pecos. The Apache, like other western Plains people who lived on the other side of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range, specialized in surviving that harsh environment as nomads, making everything possible—from food to clothing to housing to utensils made from horn—from every bit of the buffalo. They were no doubt thrilled to get some tasty corn to accompany all that meat.

Pecos, meanwhile, was happy to buy tasty buffalo meat and nice warm buffalo hides. Downside? The Apache knew where Pecos was, knew it had stored corn, and knew that in times of desperation, it could be raided. This might help explain Pecos’s fearsome reputation as warriors, with an army of 500 specialist soldiers.

Pecos Rising

As Pecos prospered, people from smaller villages nearby moved into the Big City of Pecos, for all the advantages of city life (more goods, more variety, better housing, and better defense). To shelter people and store food, many peoples in the region built what the Spanish would later dub pueblos, or "towns.”

Throughout the region, people lived in steep valleys, and homes were often cave dwellings that had been carved into the soft cliffside rock. I wrote about an ancient pueblo in nearby Arizona, not too far from the Grand Canyon. When you’re a Nonnie (paying annual or monthly subscriber to Non-Boring History, you get to choose your own adventure, with access to more than 500 of my posts, fresh as a daisy, and searchable by keyword. Like this:

In some cases, pueblos had more than a hundred rooms each by the 14th century, the century of Geoffrey Chaucer and of the Black Death, a devastating global pandemic which only the Americas escaped.

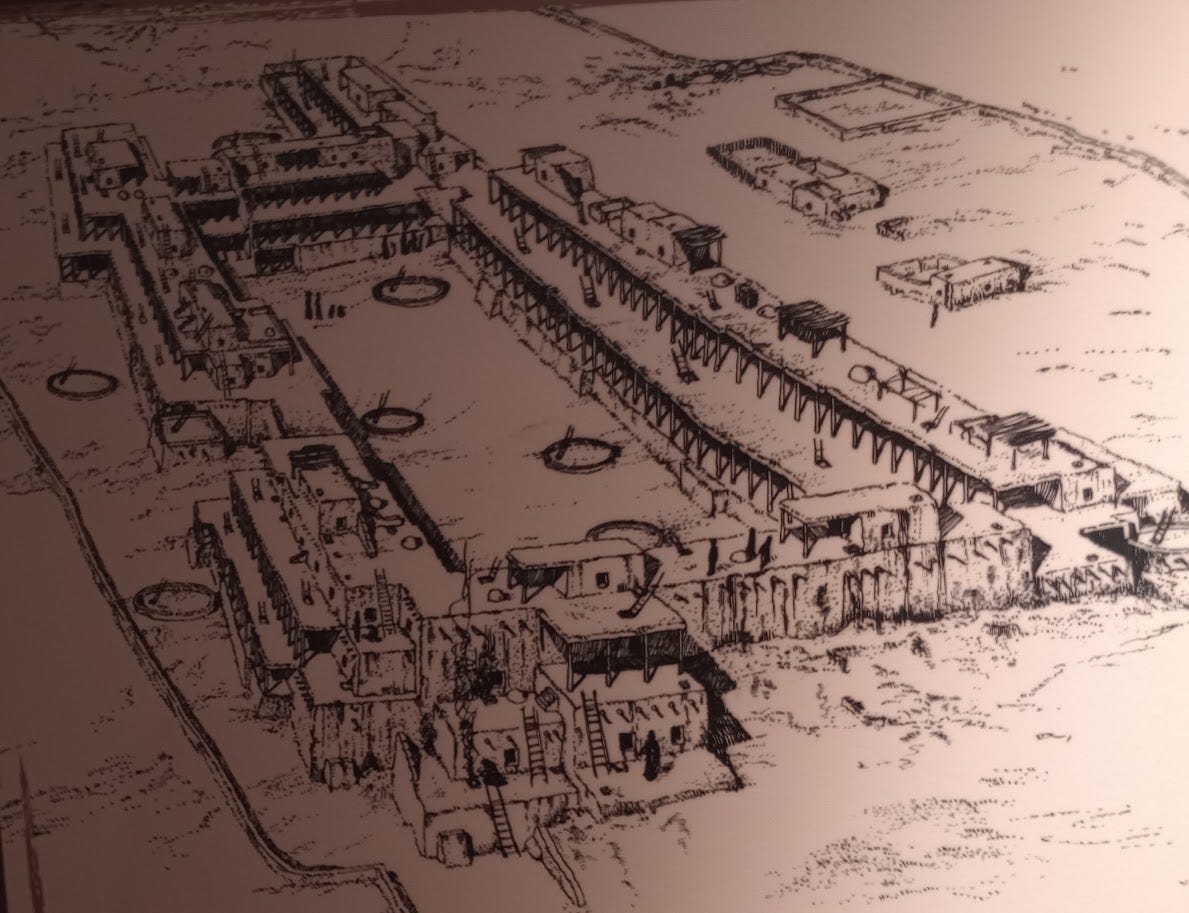

Pecos was the most important pueblo of all. It was not in a steep valley with cliffsides, however, but on a mesa, a flat-topped hill. So Pecos people built the next best thing to cliff houses, multi-story buildings, up to five stories high by 1450, made from stone, with clay as a sort of plaster on the outside. Oh, and the builders were women. Yes, women.

By 1450, Pecos was the major regional hub, and home to about 2,000 people:

Here’s an artist’s 3D impression from the museum:

Like most societies, Pecos remained anchored to the past in its faithways. Kivas, round buildings dug into the ground like those early pithouses, were the city’s holy places. Here, prayers were said, kids educated, and rituals observed.

Several traditional kivas survive at Pecos National Historical Park, mostly without coverings or ladders. Signs warn visitors to keep out, but I needed no encouragement.

One kiva, however, is capped off in the traditional way, and visitors are encouraged to descend inside on a traditional ladder:

Like this:

“Not on your nelly,” I said to Hoosen, using a traditional British expression meaning “Oh, hell, no.” The museum had urged us to treat kivas with respect, which was fine with me: I had no desire to arrive in one at great speed and flat on my face. Hoosen agreed that descending into this sacred space was not likely a great option for us. We let younger tourists explore and report back, but their description was vague enough to persuade me we had made the right decision.

This trail was fraught enough with danger as it was, thank you. At one point, Hoosen suddenly grabbed my arm, and pointed to the ground: A young rattlesnake was slithering across our path. A few minutes later, we met with a grandmother, mother, and toddler who had already seen two rattlesnakes. I hope you appreciate the tremendous risks we take on your behalf! Oh, yes!

But I digress from contemplating the glory that was Pecos.

Within four decades of Pecos achieving its greatest glory, and thousands of miles away to the east, a lost Italian sailor, commissioned by the Spanish government to find an easier route to Asia, instead stumbled on the islands of the Bahamas.

Things were about to change. Big time.

Diverse people had long passed this way on the major travel route through the Glorieta Pass, bringing news and ideas to Pecos as well as goods. As a settled people, the people of Pecos valued and needed peace and stability. But their location, high on a ridge, brought them to the attention of strangers, and so they were also prepared for war. They had chosen to settle on this ridge for a defensive reason. They maintained an army. None of this would be enough when the Spanish arrived.

And the Spanish were on their way toward Pecos from Mexico by 1540, just twenty years after defeating the Aztec Empire, okay, yes, mostly by accident in the form of smallpox and other Old World diseases, but overwhelming defeat just the same.

Nobody Expects a Spanish Incursion (much less several)

Gold In Them Thar . . . remote places in the far distance

The first Spaniards to arrive at Pecos were soldiers in 1540, led by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. They came not for conquest, but in search of gold, the pretty shiny bling that has driven so much world history. The people of Pecos, learning of Coronado’s quest, had the good sense to gesture vaguely toward the northeast, to somewhere far, far in the distance where (they assured Coronado) there was loads of gold, tons of it, they were certain.

Coronado and his men got as far as the area of modern-day Salina, Kansas, before they realized they had been had.

This clever distraction actually bought Pecos quite a bit of time, more than a half century. But it was a matter of time: A Spanish governor, Juan de Onate, arrived in New Mexico in 1598, along with 400 colonists, Franciscan missionaries, and heavily-armed soldiers. Pecos was clearly a major place, and de Onate soon had his sights set on it.

His goals? To convert the inhabitants of Pecos into Catholics and thus (not incidentally) loyal Spaniards, practicing an economy based on ranching, farming, and trade. To that end, he sent Franciscan friars to Pecos, supported by Spanish soldiers in case anyone in town voiced any objections to the new religion. Eager to hurry the process along, the friars demolished kivas and destroyed sacred objects, to put an end to traditional rituals, and offered up Christian holy objects instead. Like these.

If you suspect that all this destruction and disrespect made the Franciscans unpopular, you are absolutely correct. Only in 1621 did a friar with a clue turn up in Pecos. Fray Andres Juarez had the good sense to show respect to Pecos culture, including language and faith, even while slyly continuing to try to convert people to Christianity. This, as it happens, was a far more successful strategy than bluntly attacking traditional beliefs, as the Jesuits could have told him, and the New England Puritans never quite figured out.

What was in conversion for the people of Pecos? This was indeed a new world, and conversion offered status, power, and favors from the Spanish. That was hard for some to resist. But consider too that the population of the pueblos of New Mexico may have dropped by up to 90 percent in the years after the Spanish arrival, thanks almost entirely to the introduction of Old World germs. That was devastating, and if the experiences of Natives elsewhere in the Americas are any guide, may well have caused a massive spiritual crisis.

So in 1625, the Pecos people built a huge church under Fray Andres Juarez’s management. The biggest church north of Mexico, it’s said:

Some Pecos people became Catholics. This does not mean they all became Catholics, or that they were enthusiastic about building churches, paying taxes on goods, and being brutally punished when they failed to do either. When traditional worship was again driven underground, discontent came to a head.

As if that weren’t bad enough, the Apache often raided Pecos. Neighboring Navajos also attacked often. Tensions were riding high. Something had to give. And it did.

The Popé Fights Back

By 1680, it’s safe to say the Pueblo peoples, including those of Pecos, were generally fed up, and nobody was more fed up than Pueblo spiritual leaders. Most fed up was Popé, who, my undergrad professor hurried to point out, should not be confused with the Pope. To avoid confusion, Popé’s name can also be spelled Po’pay, but where’s the fun in that?

Campaigning on a popular platform of prosperity and kicking Spanish butt, Popé formed an alliance among many of the pueblos, and with a firm date for an uprising: August 10, 1680. Without writing, the pueblos needed something tangible with which to mark the date, and they got it: At a meeting, every pueblo representative was given a rope full of knots, each representing a day until the Big Event. Each day, a knot was unravelled.

On the day, Pecos people demolished the church, and while some converts helped a friar escape, another was killed. The Spanish ran off. They did not return.

This uprising, known as the Pueblo Revolt, was the most successful Indigenous rebellion in the history of the US.

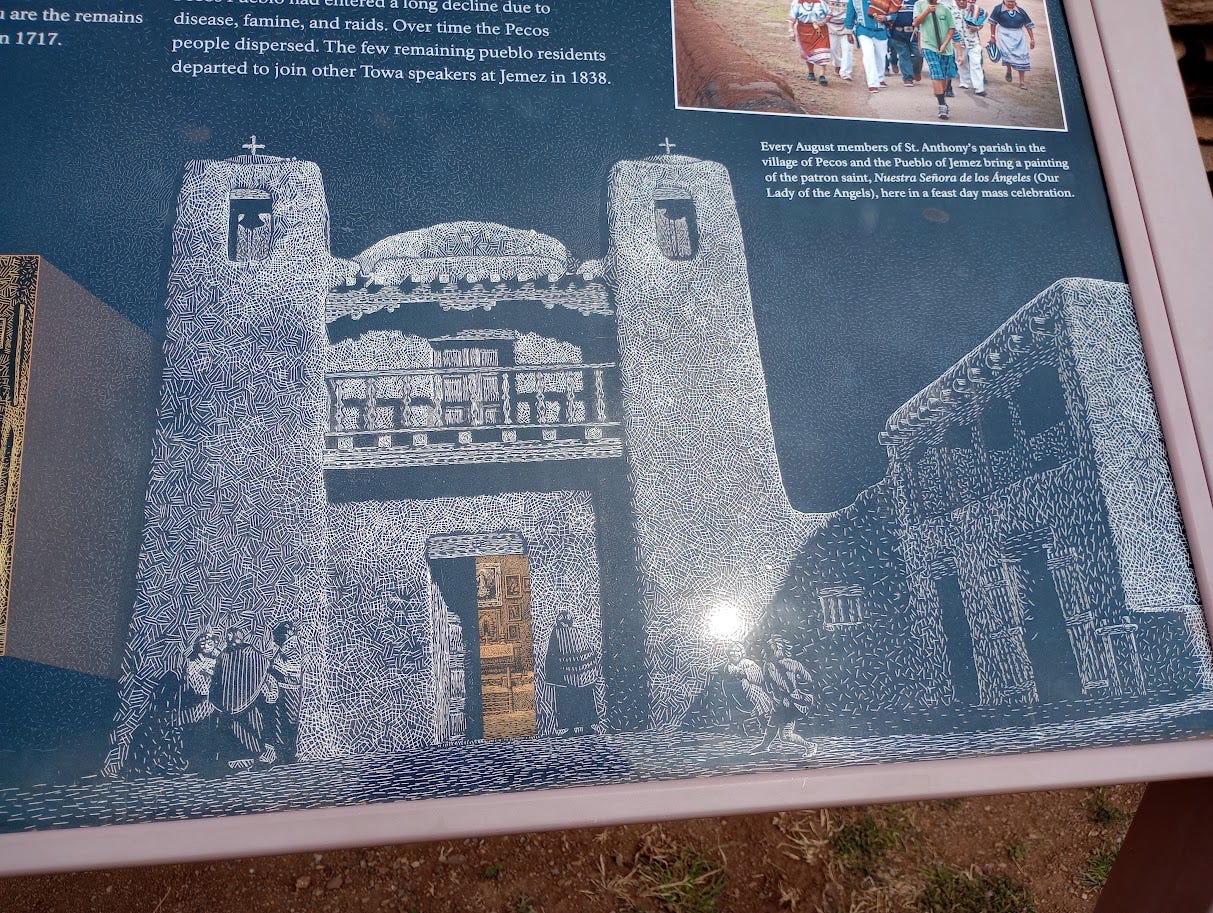

The departure of the Spanish, of course, was not the end of the pueblos’ troubles. Pecos continued to contend with lack of rain, and attacks by Apaches and Navajos. So we should not be too surprised to learn that when the Spanish, much humbled by the Pueblo revolt, sheepishly returned in 1692, they were given a cautious welcome. By 1717, the Franciscans had built a smaller church, the remains of which can still be seen today.

And here’s how that 1717 church looks now. I wish we could have done it justice. I gasped when I first saw it. Bear in mind: It’s not only smaller than it was, but it was always much smaller than the original church.

Nobody is quite sure why there’s a kiva right alongside the 1717 church, but this might be a mark of a kindler, gentler approach to conversion that yielded dividends for the Franciscans in a place where forced conversion had led to the disaster of 1680:

“If this is the small church,” I said to Hoosen, “and it’s lost height over the centuries, I can’t even imagine how big the original church was.” Apparently, it was three times the size. That boggles the mind.

Pecos’s troubles were not over, now that the Spanish had returned on more equal terms. Drought continued. The Comanche, an ambitious horse-riding Plains people, now raided Pecos with depressing frequency, effectively making a peaceful life impossible.

But in 1779 the Spanish formed a military alliance with the Pueblo peoples against the Comanche. At the same time that the British coast of what’s now the United States was involved in a little event we remember as the American Revolution, or the War of Independence, the Spanish and the Pueblo peoples were fighting the Comanche together. They won. A peace treaty was signed, in 1786, just a few years after the British and Americans signed on the dotted line (by coincidence, but a fun coincidence).

More and more, the cultural lines between Spanish and Pecos blurred. From metal tools to Catholicism, from the Spanish language to guns and ranching, what was Spanish and what was Pecos became increasingly intermingled.

Change Changes at Pecos

Change never ends. Mexico got its independence from Spain in 1821, and after that, huge conestoga wagons, the trucks of their day, trundled along the Santa Fe trail. They brought hardware, wool, wine, and more from Independence, Missouri, to the city of Santa Fe, formerly the center of Spanish power in the southwest. In exchange, the wagons returned east with gold, silver, and furs.

The big wagons passed Pecos, and stopped there, but as ranchers and farmers moved in, Pecos was withering away. So passing traders increasingly did business at a trading post on a ranch owned by Martin Kozlowski, a Pole who had married an Irishwoman while he lived briefly in England, and who discovered New Mexico during his service in the US Army, before settling down there. In 1862, Kozlowski’s ranch was home to Camp Lewis, where Union soldiers based themselves for the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

When the railroad arrived in 1880, that was the end of the Santa Fe trail. Kozlowski moved to Albuquerque, where he died in 1904. By then, Pecos was long gone.

In 1939, an oilman named Buddy Fogelson bought Kozlowski’s ranch. A few years later, after WWII, Fogelson married a British-born film star named Greer Garson, and she came to live there with him. But we already covered that.

For a long time, the Pecos people were assumed to have vanished, and we do love our long-lost mysterious civilizations, don’t we?

Let’s Not Be Hasty

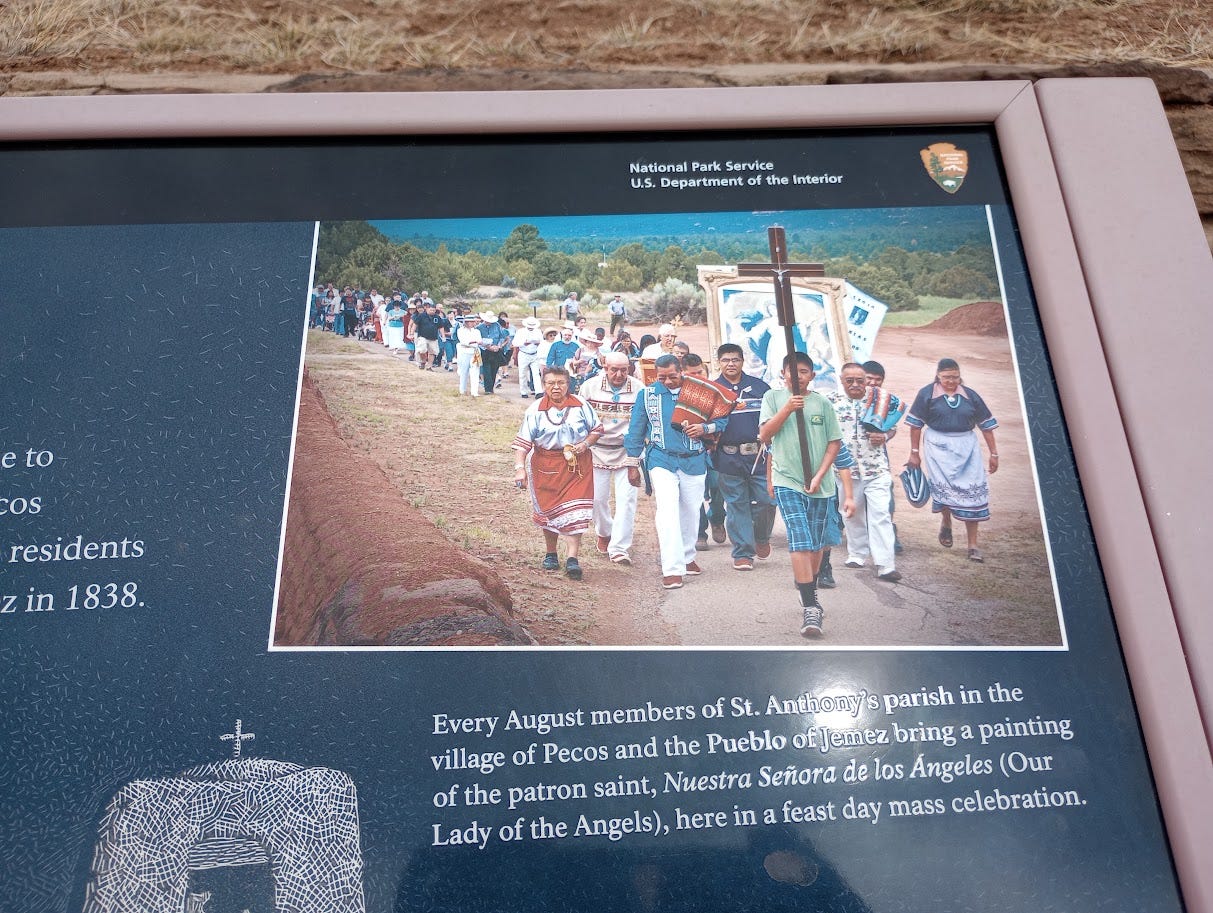

Rubbish. They did no such thing. People tired of drought and war had been moving out of Pecos for a long time, but they did not disappear. In 1838, almost a century before Buddy Fogelson bought Kozlowski’s ranch, the last of the Pecos people moved to nearby Jemez Pueblo, bringing their unique culture with them. They’re still there, still practicing a culture that began in Pecos. They live as respected members of the sovereign nation of Jemez Pueblo, while retaining their distinctive beliefs and practices. Many still speak the Pecos version of Towa, one of the six Pueblo languages, almost all speak English, and many also speak Spanish, making them trilingual. They also practice Catholicism and traditional rituals, including those held at Pecos itself, which is held sacred. The “Latino” label pastes over massive ethnic and historical differences among Spanish speakers in the US. No wonder it can be confusing!

Many of us have a hard time imagining multiple identities, blended identities, but these are the norm in history. People have always lived with contradictions that only appear to be contradictions to outsiders.

There’s something else: When I first came to the American West, I was bored by the dry landscape which had no apparent history, little human presence, and no info panels or other indications in most places that I was wrong. The historical markers that did exist were dreary, to say the least. The museums sucked.

Now, decades later, the improved National Park Service museums, Native museums, outdoor info panels, and so much more are delightfully bringing to life a Western American landscape soaked in human history, and populated by the descendants of the peoples of that past. Americans, Brits, and others who have blithely asserted that America has no history have always been wrong. Now, I can say with confidence that American history just might be the most fascinating of all: Not just Pecos, but the whole continent (Canada, too! Which is, let's be clear, an independent nation!) has served as a crossroads for world change.

Come to Pecos National Historical Park, plan ahead, allow at least a couple of days (unlike us), and be richly rewarded: The ranch of Buddy Fogelson and Greer Garson, and Martin Kozlowski before them, is part of the Pecos National Historical Park. NPS rangers offer all sorts of talks and walks, some on request, so do get in touch with them before you go. If you want to visit Jemez Pueblo, please note that, from what I can gather, the people of Jemez warmly welcome guests to their visitor center and public events, but they have very strict rules about tourist behavior. Photography and writing about certain cultural practices is prohibited. So is tourists driving through neighborhoods. Perhaps we should expect nothing less from a people who learned the hard way that being the center of the action and attention is a mixed blessing.

When you’re a monthly or annual subscriber, you’re guaranteed a place on my mailing list, searchable access to more than 500 posts, and so much more! Plus you’re supporting me to raise public awareness of the value of nonpartisan academic and public history.

Details here: