Travels with John

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Visiting the 20th century American author who wrote about migrants, especially himself

New Reader?

Welcome to Non -Boring History! This is an Annette on the Road post at historian Dr. Annette Laing’s Non-Boring History. I'm historian Annette Laing, a non-fancy person with a PhD in early American and British history, and, with me, you’ll visit places you almost certainly would never go yourself and books you never thought to read. That's how I roll at NBH!

To find out more about Annette Laing and Non-Boring History:

Mark Your Calendar for the next NBH online Sip ‘n Chat! Topic: Historical Travel

This coming Sunday, July 20, 2025. Details at end of post!

Prologue: The Wrath of Grapes

Never out of print. Never irrelevant. Never far from controversy. The story of the Joads, a poor family of farmers, forced off their land in 1930s Oklahoma, who become migrant farmworkers in California.

That’s an artist’s rendition of a family like the fictional Joads in John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. I'm convinced the images are of Steinbeck and his family, who never lived as migrant farmworkers, except perhaps in Steinbeck's imagination. The real Joads were rural people displaced by drought and economic depression. They followed the crops in massive fields as each came ready to harvest, reaching up for fruit and bending down for vegetables. It was backbreaking labor. Families earning less than survival wages as they raced to fill the buckets by which they were paid. Most were housed in miserable shacks. Practically everything I just described is still true, more or less. Last time I was in California, I watched farmworkers hurrying, running, down the vegetable rows, while gently clutching buckets.

What are the words on the man’s chest? That’s a quote from The Grapes of Wrath. It's Pa’s reply to being told that the leaflets that attracted him all the way to California, promising an idyllic life picking fruit, had maybe not been truthful.[Transcription is below]

“Pa said, What the hell you talkin' about? I got a han'bill says they got good wages, an' lit-tle while ago I seen a thing in the paper says they need folks to pick fruit.'.... 'My han'bill says they need men. You laugh an' say they don't. Now which one's a liar?'"— John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

By the time men like Pa and women like Ma and the kids had invested every last dollar to travel all across the western deserts to California, it was too late to realize they'd been had.

John Steinbeck did not write only from imagination: He knew these places, and got to know the people who toiled in them. He was curious, he read, he visited, he listened, and that's what made his writing ring true.

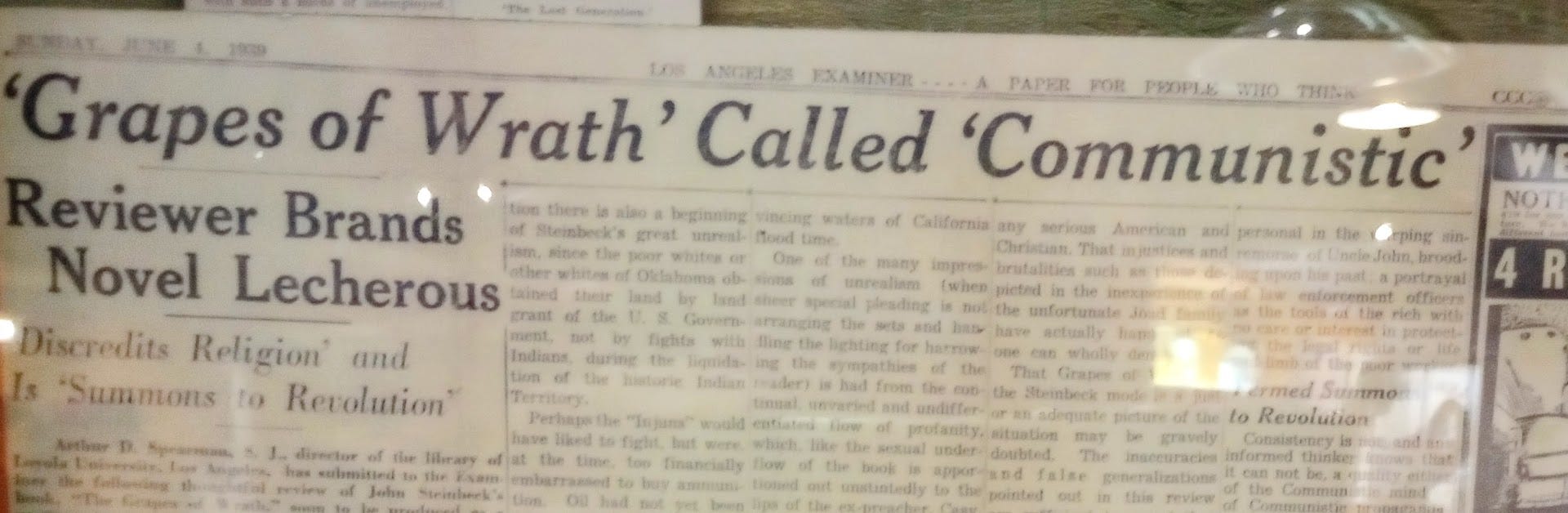

Not surprisingly, Grapes of Wrath did not please California’s big landowners, who depended on migrant workers to harvest thousands of acres, or California’s business boosters, who were selling the California Dream of a good life. Angry responses to Grapes of Wrath included this leaflet:

“Grapes of Gladness” doesn't have quite the same ring, though, does it?

Annette Struggles with John Steinbeck

Yes! Today we're visiting a museum that's all about legendary American writer John Steinbeck and his books. Hardly read Steinbeck? Never read Steinbeck? Ooh, shocked, I am! For shame!

Me? I’ve hardly read Steinbeck. And yet . . . the first American novel I ever read was at school in England, and it was John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.*

*Fun fact: Brits pronounce wrath as wroth, and it took me time, and a lot of funny looks, to unlearn that pronunciation in the US.

I read Grapes at school, and not by choice. As a British teen, I struggled, because everything in Grapes of Wrath, language, places, cultures, history, was unfamiliar. I also struggled with Steinbeck because his work was so bleak. Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, which we also read in class, was even more of a barrel of laughs than Grapes (sarcasm intended).

I don’t think Mice and Men is even taught in Britain anymore, because of racist language, which of course teenagers have never, ever heard before. Ever.

That’s the thing about Steinbeck: He continues to offend as he did in his lifetime. He offended all sorts of people across the entire political spectrum and beyond, whether liberals or conservatives (however you interpret those labels) Nazis or Communists. Still does.

Steinbeck called things as he saw them, and that’s always a dodgy proposition if you want everyone to like you (not that Steinbeck did). It also makes for great writing.

My teenage struggles with Steinbeck were not unusual for me: I struggled with every author I read for English class, from Shakespeare (which we started at age 11, in a mostly working-class town no less) to Sylvia Plath (another American, now I think of it).

But John Steinbeck was in a class of his own. While misery reading could be very engaging for a teen, it was also exhausting. I mean, Shakespeare included a dirty joke for every horrid death. And even Sylvia Plath’s poetry could seem a little more cheerful if I read it with both eyes half-closed. But Steinbeck let us have adult life right between the eyes, both barrels.

Despite my struggles with Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck stayed with me.

After I came to live in Steinbeck’s native Northern California, I did try his books again. I vaguely remember reading Tortilla Flat (1935), also written during the Great Depression. This was his first successful work, praised by critics and readers alike. It didn’t grab me.

Cannery Row, set among the sardine canning factories in coastal Monterey, California, did work for me. Maybe because by then I had visited Monterey, and eaten Mexican food at a restaurant perched on the very edge of the Pacific, on the real Cannery Row. Well, sort of real. Even by then, in the mid-1980s, Cannery Row had become the tourist trap it remains today. Why did the canneries close? What had become of the sardines? As Steinbeck's friend and marine biologist “Doc” Ed Ricketts explained, “They're all in cans.”

Most recently, I read and finally loved a Steinbeck book, a work of non-fiction about his road trip with his dog. Travels with Charley was a gentler sort of book written by an older man.

Maybe my Steinbeck experiences aren’t typical, I thought? So I consulted my long-suffering spouse Hoosen, a normal American bloke. He has read Grapes, The Pearl, Of Mice and Men, and mostly (like the great majority of Americans who have read Steinbeck) he read them in high school.

Let me spell this out: I’m an historian of early America and Britain, not a Steinbeck expert. Today, I'm writing about highlights of my travels around the National Steinbeck Center in John Steinbeck's hometown, Salinas, California. That experience is unique to each visitor. The bad news? I'm no Steinbeck expert. The good news? Like virtually everyone else, I'm no Steinbeck expert.

So what else did I bring to the Steinbeck museum experience?

Visiting the National Steinbeck Center, I arrived wearing many writing hats. I came as a reader who had trained as a journalist and as a PR flack. Once upon a time, I was award-winning investigative reporter and then editor of my California university’s newspaper, and at the same time I churned out press releases and other official tripe for the university’s PR office, while never mixing the two. That's impressive, now I think about it.

I came to the Steinbeck museum also as a trained historian who's written scholarly and boring history. And as the author of four historical time-travel novels, which are pretty good according to Kirkus.

I’ve found joy and income in every kind of writing I’ve tried, except in writing a private journal for myself, which I’ve never succeeded in doing. I need an audience, I guess.

Journo, PR flack, historian, novelist. Yet I’ve never wanted to identify as a writer. Why? That would have force-teamed me with all sorts of ghastliness, like pretentious and tedious modern literary fiction. Most of it seems to be produced by those who are more writers than readers, taught in formal classes to write in the same snotty voice, and who huddle close together in the cities where such people congregate and agree with each other.

So I prefer to call myself a public historian, even though that doesn’t quite capture my solitary mission: Most public historians work at museums. I sit at my computer, read books in a comfy chair, sometimes give talks for real people, including teachers, and kids, travel long distances by car, and most of all, write in a steady stream, and edit my own words with an unsparing viciousness that would surprise you.

That said, I would be thrilled to be called a writer in company with John Steinbeck. Steinbeck wrote fiction, non-fiction (including news features), and even speeches for Democratic Presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson. He brought to his writing not merely a raw ambition to be published, in the modern way, in a time in which concern for celebrity and wealth trumps all else. John Steinbeck had a physical need to write, and he gave us writing that was informed by a lifetime of reading books, and of living a real life among real people.

No, I am NOT comparing myself in any qualitative sense to The Brilliance That Was John Steinbeck. But OK, yes, I feel a pang of kinship. Just a little one.

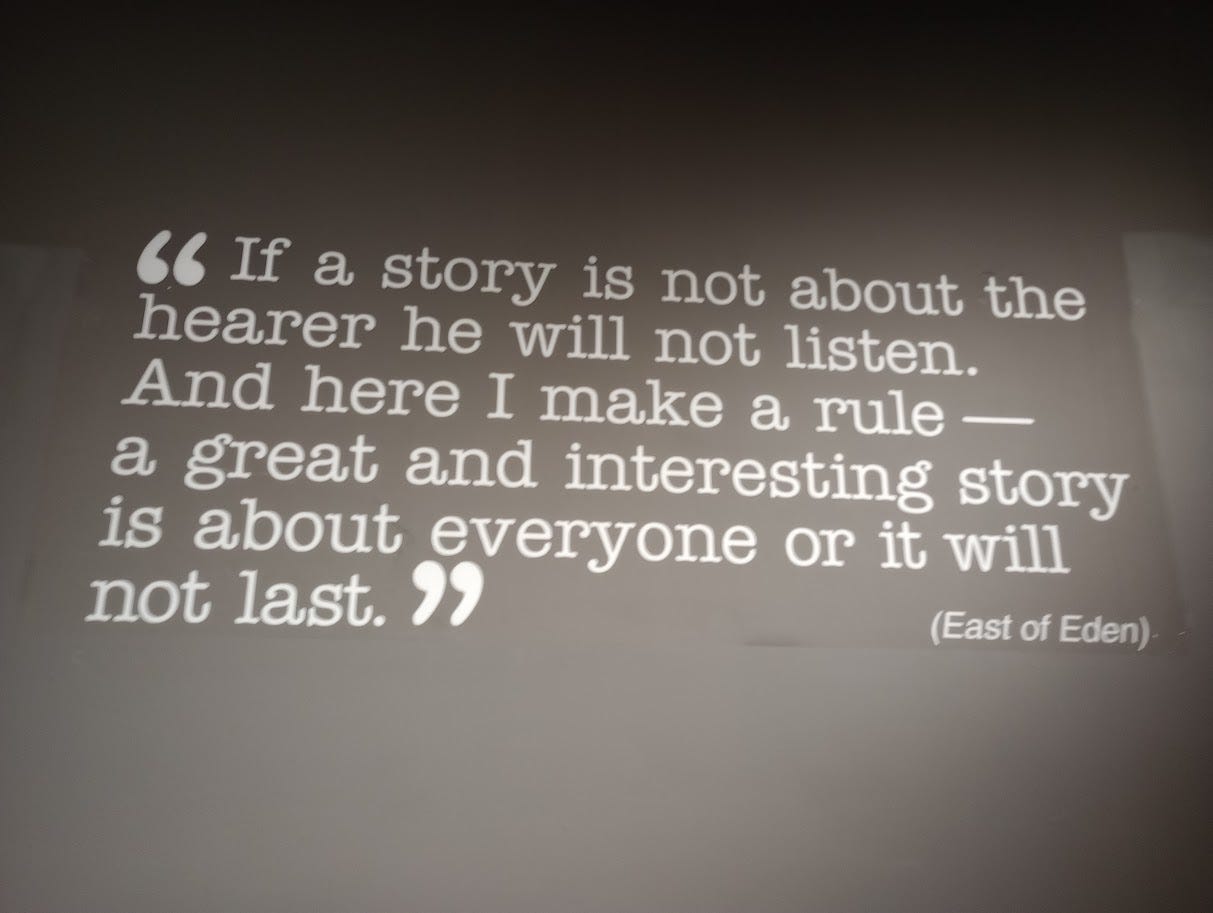

No, I would NOT want to hang out with John Steinbeck. He was difficult, I’m difficult, and I could see us circling each other like sumo wrestlers, observing, assessing, and then going in for the kill with the written word. It would be a brief contest: He would annihilate me in short order. My feeling of kinship with Steinbeck, as I read his words now, is an illusion he planned for his readers, a trap to draw me in, to draw in everyone he can, using every reader’s self-centeredness as bait. As he wrote in East of Eden:

I nodded when I saw this quote. But then, I thought of my long reluctance to read Steinbeck.

In my head, I’m not any of his characters. Now that I read him as a grown-up, I realize I’m standing alongside him, as he shows me those alien worlds of his. These are hard worlds, the worlds of 1930s migrants, workers, the uneducated, the poor, the powerless, of soldiers in battle and women living nightmare lives as housewives and whores. John Steinbeck did not turn away in disgust or embarrassment. He leapt right in, taking us with him, even in the most terrifying situations: WWII. Vietnam.

Laing, aren’t we ever getting to the museum?

Oh, didn’t I mention, reader? We’re already there.

Travels to Salinas with Hoosen

So the National Steinbeck Center (as it is formally known, or NSC, as I will mostly call it) is in Salinas, not the best-known place in California, and this museum was not an obvious pick for me or Non-Boring History.

The NSC is billed as a literary museum, rather than as a history museum. I’m no expert on literature, and not at all knowledgeable about John Steinbeck. But one continuing theme of Non-Boring History is that while a great museum is never really a great place to learn things properly (that’s what books are for), it does get us interested in reading more.

One clue to why this museum belongs right here at NBH: John Steinbeck was not a historian, but he was writing about the world he lived in, and creatively, too. As historians will tell you, fiction and creative nonfiction can get at things that proper history too seldom does: The taste, touch, smell, feel of a time and place, the unspoken thoughts that might have occurred, the spoken thoughts that went unrecorded. That’s why history professors sometimes assign novels to our classes.

Hoosen and I had only popped into Salinas for the National Steinbeck Center. Most of Salinas today looks sprawly and samey, like most American cities. In Steinbeck’s early 20th century childhood (he was born in 1902), Salinas was growing, a small town with big aspirations. But it was absolutely still a small town of between three and four thousand people. This small-town image was so fixed in my mind that I didn’t even notice, on our brief visit, that it’s no longer true: I am astonished to learn now from the Internet that about 170,000 people live in Salinas.

The National Steinbeck Center is in the old downtown, a place Steinbeck could still recognize.

Hoosen and I drove back and forth a couple of times, confused about the whereabouts of our destination despite the insistent squawk of our GPS [UK SatNav] announcing that we had arrived.

The National Steinbeck Center doesn’t stand out on the street: It’s inside a generic modern and multipurpose building owned by California State University at Monterey Bay’s local branch. We finally spotted the place hiding in plain sight, and found parking in the multistory garage next door.

As we wandered into the lobby, local people clutching papers and computers were just drifting out of an official-looking meeting I assume was unrelated to Steinbeck, except maybe in the loosest sense.

East of Eden

Much as I was drawn by the sights of this first big room of the National Steinbeck Center (above), the movie (East of Eden, it turned out), the Model T, and the general flashiness, it was a bit overwhelming.

So I stopped first to read the small display (at left) about John Steinbeck’s family, and another exhibit (entrance on left) about Steinbeck’s childhood.

John Steinbeck was born and raised in Salinas, on the western reaches of the agricultural torso of California. Every inch a Californian, Steinbeck was a migrant born of migrants, restless people who moved for adventure and idealism as much as for economic opportunity: His grandparents were German immigrants who had met in Jerusalem before coming to America.

And like most talented people who start life in small towns in America, yes, even those in supposedly glitzy California, Steinbeck fled as soon as he graduated high school. Yet he was drawn back to Salinas in his mind, over and over, even as his travel horizons expanded.

I can attest to this: Writers carry everywhere, everyone, everything with us, consciously or not. That’s very hard on the soul, but great for the writing. These are shackles we would rather not lose. I know this in my soul, because my first novel took me to a fictionalized version of the English town I grew up in, a place I never wanted to return. In my book, I pushed it back in time to World War II, the event that had haunted my 1970s childhood. Without meaning to, I wrote a character based on a woman who had haunted me ever since. And then I flew to England just to see her, and I'm still not sure that was a great idea, but I did.

Sorry to keep connecting and implicitly comparing myself to Steinbeck, which is awkward. But the NSC spurred these observations, and it’s a hint of how it hooked me. Everyone reacts differently to every book or museum, as with everything, but I really think there’s something here for most of us. All of us, if we're open to it

John Steinbeck’s parents weren’t rich. They weren’t New Yorkers, or San Franciscans. Salinas wasn’t San Francisco, and it certainly wasn’t New York. This was the back of beyond as far as the big cities were concerned, flyover country.

But the Steinbecks weren’t poor, either. The family home, pictured below, then and now, today would cost a pretty penny, even in Salinas. In 1902, the Steinbecks were middle class, okay, perhaps upper-middle class by small-town standards.

John Steinbeck’s parents were readers and doers: His mother, Olive, was an educated New Englander (of course! America's most educated region since 1620) Olive, a former teacher, was the type of Small-Town or Village Lady Who Organizes Things. John's father, also named John, was the county’s treasurer, a man who worked in an office.

So Steinbeck’s family was comfortable, and, above all, stable and loving. John's was not the impoverished childhood of so many of his characters. That’s what the Home and Family exhibit at the NSC hammered home.

Read this quote from Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden, on the NSC wall, because even though I don’t think it’s on point about Steinbeck’s real family’s economic status and educational wealth, it certainly seems to sum up who they were:

Steinbeck didn’t like school, I learned at the NSC, a useful reminder that a love of school and a love of learning are not always the same thing (transcript of relevant quote below):

“I remember how grey and doleful Monday morning was. I could lie and look at it from my bed, through the rusting screen of the upstairs window.... What was to come next I knew, the dark corridors of the school...and the teachers, the weekend over, facing us with more horror than that with which we faced them."—John Steinbeck

Fortunately, he was not put off reading and learning. After high school, Steinbeck enrolled at Stanford University, majoring in English Literature, rather than in a creative writing course, because those did not yet exist, which was almost certainly helpful: Imagine anyone trying to teach Steinbeck how to write fiction. Talk about trying to teach your granny to suck eggs.

He stuck around Stanford for five years without graduating. But formal education has its uses. School and university stretched John Steinbeck to read books he might not have chosen for himself. In another quote on the museum wall, Steinbeck says he came to think of the books he read in school, like Crime and Punishment and Madame Bovary, “not at at all as books, but as things that happened to me.”

That’s the kind of imagination that only reading good fiction can cultivate. Hint to us all in an age when smartphones have scrambled our brains.

By this time at the NSC, I was warming to Steinbeck. Like most people, I hadn’t liked most of my school lessons, and I wasn’t a great student. I’ve since learned (to my eternal smugness) that this is often the case with bright kids who are frustrated with being forced to study what just doesn’t interest them. But as a professor, I come to see the value of locking young people in a room and making them listen, and of reading at least some books we wouldn't pick for ourselves.

John Steinbeck was a born writer, I learned at the NSC. As a kid, he made up stories to tell his siblings. He began writing down his tales in big sturdy hardbound ledgerbooks his ever-encouraging father pinched from work for him.

But for Steinbeck, even as a child, writing wasn’t just about sitting around reading and dreaming and putting pen to paper. It was also about doing, about living as a writer, of listening, of delighting in new experiences, good and bad, whether helping with farm chores at a friend’s family’s farm, or riding his horse, or (unbeknownst to his parents, who would have been aghast) hanging out with Chinese workers as they played cards and gambled.

Everything Steinbeck did, exciting or mundane, was material for his writing, processed into stories in his head and then into paper. He marched to his own drummer, trying all kinds of jobs after he dropped out of Stanford. He found fascination everywhere.

Curiosity is not a skill you can instruct (which is, by the way, what too many people think teaching is). But it can be taught, by those rare parents and teachers who model curiosity themselves.

The NSC rewards those who have questions, who touch, who indulge even a moment of curiosity: Turn this little rotating display, and be rewarded with a funny quote from Steinbeck about his early writing (transcribed below):

“I used to sit in that little room upstairs . . . and write little stories and little pieces and send them out to magazines under a false name and I never knew what happened to them because I never put a return address on them.”

—John Steinbeck, on his youthful writing

East of Eden is the first of Steinbeck’s books highlighted at the NSC. That’s not because it was Steinbeck’s first novel, because it wasn’t. It was published in 1952, mid-career. Steinbeck did regard it as his best work. But the NSC starts us out with East of Eden because it is based on a thinly-disguised Salinas, the town in which we were standing, and the site of Steinbeck’s youth.

Alas, this was a problem for Hoosen and me. See, neither of us had ever read East of Eden, or even seen the 1955 movie with James Dean.

When we walked into that big first room in the museum, and saw that Model T, I immediately assumed it represented Grapes of Wrath, much of which is about the Joads’ road trip to California. It took me a few minutes to read, and to grasp the big title hanging from the ceiling that reads Growing Up, East of Eden, Salinas, which is a huge hint.

It was a steep learning curve, and I fell off. I only learned when I started writing this post, two months later, that East of Eden is no nostalgic tribute to Steinbeck’s hometown. To give you an idea: One character in Salinas murders her parents, and later tries to give herself an abortion with a knitting needle, because she plans another escape, this time from a marriage and Salinas. She ends up as the successful madam of a brothel, but even then, she’s still in Salinas. So that’s cheerful. Ahem. But let's get real: These things happen in real life. As ever, Steinbeck does not treat readers as snowflakes, but as grown ups. Whether we like it or not. And yet he also wields compassion and humor, and that shines through.

Now I think of it, what better novelist than Steinbeck to transport a fact-obsessed historian, resistant to being gaslit, to places past, their smells, tastes, fears, horrors, suffering, and, yes, joys?

Steinbeck’s California was not the glamorous fantasyland California that outsiders imagine, and that Californians also like to believe in, even when they know better.

In Salinas, we truly are East of Eden. Eden, I decided, is the California coast. Although technically part of the coastal region, Salinas is closer in spirit to the hardscrabble Central Valley to its east. I had forgotten (or never noticed) that the Salinas Valley, not the Central Valley, is where the Joads, the destitute migrant family in Grapes of Wrath, end up after their long drive from Oklahoma in a Model T .

Like the Joads, thousands of real-life “Okies” were drawn to the Golden State by misleading ads and flyers toward a future of happiness. Eventually, many did find a happy future, thanks to the New Deal and postwar prosperity. Two of my best friends in California were descendants, and both went to college, thanks to the postwar expansion of higher education. One earned a PhD in history. But for their ancestors, such a future had been unimaginable. They had to get though the Great Depression, as people with no resources once they lost their farms in the southwest, with no reasonable expectation of a better life, and no inkling that World War II lay with around the corner. A better life? Unimaginable. Better to take pride in survival. They followed the California crops from farm to farm as pickers, long hours in backbreaking labor, badly-paid and badly-housed, thrown out from job or wretched housing if they complained, or were sick or injured.

Grapes is a novel, but this life was real. I knew people who had lived it, but didn’t like to talk about it, or couldn't find the right words. John Steinbeck, thankfully, was called to write their story.

No wonder Steinbeck keeps calling to this historian, happy nostalgist though I am tempted to be. Real, however hard, is always more interesting than willful fantasy. I am suspicious of wishful thinking, including my own. I am especially suspicious of those who demand wishful thinking, or “positivity”—or else. So should we all be.

Although Steinbeck was born and raised in Salinas, he was a migrant, just passing through. He first left Salinas through his reading. He embraced not only the whole of America as he searched for its meaning, but much of the world. I connected with this, all of it. I’m a Scot who left Scotland because of a decision in which I had no say, moving to England as a small child for a very different life. I’ve spent my adult life in America, in California (Northern and Southern), rural Georgia, Atlanta, and now Wisconsin, but always visiting Britain, and traveling around it, every possible year, including virtually every year since the late 1990s.

In recent years, Hoosen and I have taken up traveling around America in our modern version of a Model T. I’ve never ceased to be restless. I find this makes me feel not like a total outsider, nor as a true insider, but as a friend, interested in everyone.

This is not a mindset that is common in places where people are more closely tied to the land. Steinbeck knew how such people thought, the people who stayed put, because he had grown up as one of them, and he poked gentle fun:

"The Salinas was only a part-time river. The summer sun drove it underground. It was not a fine river at all, but it was the only one we had and so we boasted about it..." (East of Eden)

And that’s one reason why the old saying is true: Once you become a migrant, you can never really go home again. The people who stay where they started have no context for understanding where they are. I am NOT singling out rural people: I’ve found just as much “small town” thinking in London and Los Angeles, anywhere people are convinced that their town is the best, based on little or no experience of living anywhere else. And one of the most worldly places I’ve ever known is tiny Plains, Georgia, population 400 to which former President Jimmy Carter brought not only tourists from all over, but world leaders.

To the NSC’s credit, because there are lots of locals on its governing board, the museum does not hide that Salinas only belatedly came to celebrate its native son, John Steinbeck. An info panel at the NSC informed me:

“Steinbeck's writings were publicly burned in Salinas on two occasions, and at times he did not feel welcome in his own home town. Yet he ultimately was honored for his achievements. A school, the main public library, and numerous businesses are named for Steinbeck.”

That “ultimately” speaks volumes, mind. Those who never move tend to resent those who do, unless they become famous enough that it reflects well on the homefolks. So often, Hoosen and I find stories like this on our travels: Become famous and rich enough, and your home town or city will eventually celebrate you. I don’t think too many of the celebrated emigrants take any of this belated love seriously. And they rarely if ever come home to live.

But that doesn’t mean that the outside world doesn’t touch upon people in a small town, and I’m not just talking about Plains again.

Salinas’s growth over the years came from migrants from China, Mexico, and Oklahoma, among many others. John Steinbeck (the father)’s parents, his father a German, had met in, of all places, a Christian settlement in Palestine. Olive Steinbeck, John’s mother, was from migrant New England stock. When faraway WWI killed boys from Salinas, Olive Hamilton Steinbeck took action. Scan this code from the museum by holding up your phone camera to the screen, and you’ll hear a short clip on YouTube of John Steinbeck himself reading from his memories of his mother’s wartime good works:

The East of Eden room showed the movie on a loop, from inside a mocked-up boxcar, the kind of open-sided freight train carriage in which the homeless and restless and Steinbeck’s characters left places like Salinas and traveled America for adventure or from desperation. I decided then and there that I needed to read East of Eden, and see the movie. That was a good sign about the museum’s impact.

But it was time to leave Salinas, at least in our heads, because the rest of the museum called, and we were running out of time.

In the spirit of John Steinbeck and all wanderers, let’s move on.

In Dubious Battle

"I had planned to write a journalistic account of a strike. But as I thought of it as fiction the thing got bigger and bigger.... I have used a small strike in an orchard valley as the symbol of man's eternal, bitter warfare with himself."

(John Steinbeck to George Albee, 1935)

I’m still mulling over the quote above. I have now read Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle. The novel begins with Jim, an ordinary young man with a respectable 9-5 city job, who has been arrested and jailed for vagrancy. Why? Because, walking home one day, he came across a street protest, and climbed up a statue of some dead local worthy to get a look at the speaker, and was arrested as a protestor.

After he’s released from jail, Jim does something striking: He goes and offers his life in service to the Communist Party, in the form of a Party worker living and working in a barebones rented office.

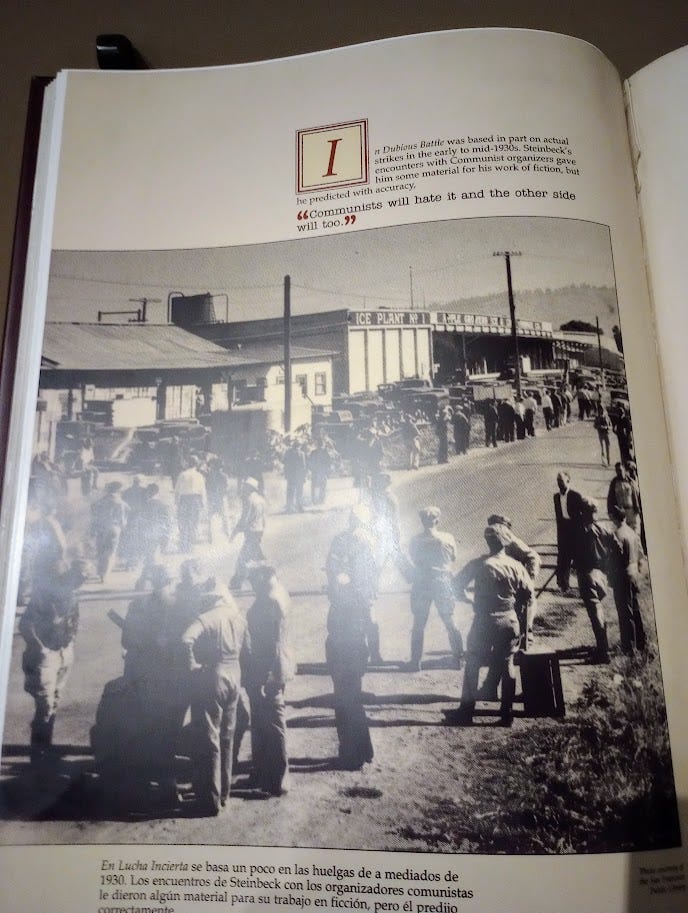

What tempted me to read In Dubious Battle was this panel on the NSC’s walls, and specifically Steinbeck’s prediction about how people would receive his book: “Communists will hate it and the other side will too.”

A novel designed to offend everyone with honesty and make every reader think? My kind of book!

Let’s look closer at that photo above:

Now I’ve learned that the actual striking farmworkers in 1930s California were mostly—80%— Mexican-Americans. That’s not mentioned in the museum or in In Dubious Battle.

Steinbeck’s story wasn’t just based on his observations of California farmworkers’ strikes in the 1930s, but specifically on the strikes of 1933, about which I knew nothing. The Communist organizer in the novel, Mac, is apparently modeled on a working-class white guy called Pat Chambers, who hated Steinbeck’s portrayal of him ever after. In real life, Chambers’s associate was not a white bloke named Jim, but a white woman named Ellen Decker, born to an immigrant Ukrainian Jewish family in Macon, Georgia.

Why did Steinbeck recast almost everyone as a white bloke? I don’t know what the critics say (time is a real issue for me when writing an NBH post). I should imagine it’s because Steinbeck himself was a white bloke, and he needed characters he felt he could inhabit as an author. Writing fiction is like that: You have to get into your main characters’ heads. For Steinbeck, maybe becoming a white woman or a Mexican-American in his head must have seemed too much to handle. He managed it later, though. Maybe he just thought that white characters would resonate with more of his readers, most of whom were white.

I don’t believe Steinbeck was a racist in any significant sense. He certainly wasn’t a Communist. Like George Orwell (1984 and Animal Farm) Steinbeck was a member of the non-Communist, indeed anti-Communist, center-left: He flirted briefly with Communism, as did many in the Thirties, but it wasn't him. He was a New Dealer, a supporter of FDR’s policies, like social security and unemployment insurance. Some tried to derail even these modest measures to offset the impact of the boom and bust cycle of the modern industrial economy on ordinary people by calling them Communism.

Steinbeck later experienced battle in World War II and Vietnam (and I’ll show you what he did, because it’s gobsmacking) against authoritarians. He distrusted authoritarianism of all kinds. He was a skeptic about elaborate ideologies and the kinds of people who slavishly followed them.

Revisiting The Red Pony

I’ve never read Steinbeck’s novel The Red Pony, which also was made into a movie. I may never read it: It doesn’t call to me. But the museum hinted to adult visitors why the subject called to Steinbeck when it did: It was grounded in his otherwise small-town childhood which included stints helping out on extended family’s and friends’ farms. And he wrote it while his beloved and influential mum, Olive, was dying:

I’m spotlighting this part of the museum because it’s a good example of how the NSC reaches out to children, too young to read Steinbeck, who are dragged to the museum by adults. The Red Pony is about kids—which helps—and the museum invites kids to think about living on a 1930s farm, doing chores:

This kind of imaginative experience has been spurned and even shamed as disrespectful in recent years. Speaking as someone who has organized history experiences for kids over several years, that’s a bloody shame: Such simulations are not realistic, nor should they be expected to be. They are, however, a hook to childish imaginations, to get kids interested. Kids need to start somewhere in learning, and they are thinking human beings with different needs from adults. Well, maybe different. I was astonished when I realized that adults were reading my time-travel novels. Then again, an adult wrote them.

Cannery Row

The NSC display on Cannery Row was pretty cool. However, I’ve already written about Cannery Row, and done so from the real Cannery Row, in Monterey, California, so I’ll refer you to that post here. I have opened it up to free readers for the moment. I can’t do that often, not because I’m a greedy ungenerous person, but because I need an income for my full-time work. I appeal to free readers for your support, knowing that few will, because most readers no longer feel any obligation to the writers they enjoy. And that’s hard.

Once There Was A War

Once There Was a War, the display on the book, grabbed me most because, well, World War II My longtime readers know I’m fascinated, having grown up in postwar Britain where The War felt like it was still on, where I was surrounded by people who had survived bombing.

Once There Was a War was also the first display of Steinbeck’s non-fiction that had caught my eye in the NSC. Published in 1958, the book was a collection of his articles from WWII, during which he was embedded with various units fighting in Europe.

This was a sign of how far Steinbeck roamed from Salinas, and even California, from idyllic small-town childhood to the exotic and the horrific. Like this (transcript follows):

Steinbeck under fire

Steinbeck was a firsthand observer during the beachhead fighting at Salerno, Italy. His graphic accounts convey the horror he felt:

"His report will be of battle plan and tactics.... But these are some of the things he probably really saw: He might have seen the splash of dirt and dust that is a shell burst, and a small Italian girl in the street with her stomach blown out, and he might have seen an American soldier standing over a twitching body. crying.... He saw the wreckage of houses, with torn beds hanging like shreds out of the spilled hole in a plaster wall...."

"He would have smelled the sharp cordite in the air and the hot reek of blood if the going has been rough.... He will smell his own sweat and the accumulated sweat of an army....”

What caught my attention most of all was that Steinbeck was for a time attached as a writer with a US Navy amphibious unit, under the command of actor and now Lt. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. had been a huge silent movie star, but Doug, Jr. became far better known in Britain, to which he moved after the War, so he may still be a familiar name to my British readers.

And then I read what Fairbanks had to say about John Steinbeck:

John, to his everlasting glory and our everlasting respect, would take the foreign correspondent badge off his arm and join in the raid. If you are caught in a belligerent action without a badge and carrying a weapon, and you are a foreign correspondent, you are shot. You don't get any of the privileges of an ordinary prisoner....

-Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., commanding officer of Steinbeck's unit

Wow, Just wow.

Check out the photo of Fairbanks (top right) and John Steinbeck (bottom right) with a captured Nazi flag:

How could John Steinbeck remain impartial in the face of the most profound evil? He couldn’t. He didn’t. True, in the middle of war, when truth was subject to the official censor, no American journalist could be objective. But a journo joining in the actual fighting? Wow. People who talk a good game about supporting troops and veterans seldom do more than slap a sticker on their cars. Real patriotism takes risk and sacrifice.

John Steinbeck greatly admired comedian (and dedicated political conservative) Bob Hope for the courage and stoicism he showed in entertaining the troops, making damaged young guys laugh as they lay traumatized in hospital beds. In a eulogy at Hope’s funeral in 2003 (he lived to be over 100), California Senator Dianne Feinstein (D) cited Steinbeck on Hope:

“Steinbeck goes on to describe how, during a song by Frances Langford, a soldier broke down in tears, and then Frances also began to cry and couldn't go on. It was then that Bob walked down the aisle between the beds and with a straight face said: "Fellows, the folks at home are having a terrible time about eggs. They can't get any powdered eggs at all. They've got to use the old-fashioned kind you break open."

"There's a man for you," Steinbeck concluded. "There is really a man."

But for Steinbeck to wade into the fighting with his soldier buddies? That’s taking “supporting the troops” to a whole other level.

Now I’ve read Once, There Was A War, I’ve learned that Steinbeck did not consider himself a news reporter, but a writer. He had been keen to let other journos in the field know that, because they felt a bit threatened by this famous author.

And, indeed, and with all respect to the massive risk all reporters take, he did not follow professional journalists’ rules. He became part of the story. That was Steinbeck.

Steinbeck in New York (not a book title)

A great American writer in the 20th century would be pretty likely to end up in New York, I guess. But I felt a pang of disappointment when I saw in the NSC that John Steinbeck had followed the road to Manhattan.

Why? I’m not alone in being fed up of so many American writers pontificating pretentiously and condescendingly from city bubbles they never leave except to visit other city bubbles, almost always traveling by plane. Did John Steinbeck just become another smug famous and rich writer in NYC?

The NSC display told me that he moved to New York in 1945, and “After that. New York was his home.”

I suppose it was inevitable. But here’s the thing: In his mind, John Steinbeck was often elsewhere, and especially, he was often at home in Salinas. In 1952, he wrote East of Eden, set in his remembered childhood Salinas.

And as a child in Salinas, he had traveled the world through books, a much more vivid vehicle for imagination than the Internet. He loved the stories of King Arthur and Camelot. Camelot never existed, but tales from that mythical place were set in the southwest of England.

So, in 1959, Steinbeck and his then-wife ( he had three in the end) rented a place with the kids for a few months in Somerset, English county of the King Arthur legend, so he could research a new version of the old story, based on the 15th century classic he had enjoyed as a kid, Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory.

King Arthur was very fashionable during the late 1950s. In 1958, the year before the Steinbecks crossed the pond, T.H. White had published his novel The Once and Future King, also based on Mallory. This, in turn, became the musical Camelot. Camelot’s connection with the later Monty Python and the Holy Grail is less certain, as is the connection with the brief presidency of John F. Kennedy: Kennedy’s favorite musical was allegedly Camelot. After his assassination, Jackie Kennedy compared his presidency to Camelot using a line from the musical (“for one brief shining moment . . .”) in an interview with historian/Kennedy fanboy Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Maybe the idea was put in her head by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (about whom I’m reading now), but I don’t know. Yet.

Meanwhile, to show you how talented and wonderfully obsessive Steinbeck was, he did the actual medieval-style calligraphy in his book’s dedication—in Old English!- to his sister Mary.

He never finished the book, but the incomplete manuscript was published as The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights after his death. In his lovingly-crafted inscription, Steinbeck signs himself, again in Old English, Jehan Stynebec de Montray (John Steinbeck of Monterey, Monterey being a more impressive place to be from than Salinas)

The Winter of Our Discontent

The Steinbecks loved their time in England in 1959. But coming home from beautiful Somerset, and from contemplating the imaginary chivalrous lives of King Arthur and his knights, was a culture shock for John Steinbeck.

He looked at 1959 America anew, and he did not like what he saw. He did not hesitate to express his disappointment and dismay in a letter to his Swedish friend, the Secretary-General of the United Nations:

"It is very hard to raise boys to love and respect virtue and learning when the tools of success are chicanery, treachery, self-interest, laziness and cynicism...."

—John Steinbeck to Dag Hammarskjold, 1959)

As a historian, I can neither agree nor disagree, because I am not John Steinbeck, and this doesn’t describe the America I came to know and love in California in 1981. I can only say that Steinbeck’s assessment was sweeping and grumpy, perhaps made more so by his knowledge that his health was in terminal decline.

One last book before hitting the road: A book Steinbeck wrote, second from his last, about hitting the road in search of an America he was afraid was transforming beyond recognition. I know it’s hard to imagine the prosperous age of Eisenhower and then Kennedy as a troubled and troubling time, but the more I read about it, and I am, it’s hard to escape that, for many Americans, it wasn't that simple.

Travels With Charley: In Search of America (1960)

Unless you’re very new to Non-Boring History, you know that this historian learns her history mostly from books, but also on the hoof. My roadtrips have a lot in common with John Steinbeck’s epic journey around America. No, really! Look:

Steinbeck traveled in a camper van. I stay in economical but non-dodgy hotels.

Steinbeck traveled with his best friend: His dog, Charley. I travel with my best friend, my long-suffering husband, Hoosen.

Steinbeck was keen to see what’s now dismissed as “flyover country” (places like Salinas, where he grew up). So am I: I now find most big cities weirdly boring. Practically every travel article I read these days talks about the great coffee I can get in such and such big city, from London to Los Angeles. I'm here to tell you that there’s practically no small town of size left in America in which I can’t get a decent latte (or sushi, come to that). Boring.

Steinbeck, as we shall see, found America increasingly “samey” when it came to the food. I wonder what he would think now.

In the early 1960s, Steinbeck traveled America in search of America, already as unhappy with how things were going in his country as Paul Simon would be more than a decade later, when he wrote American Tune.

In my long residence in America, I’ve always thought of this country not as one place to be searched for, but many places as one, e pluribus unum (out of one, many), as the saying goes on US coins. I’ve now lived for extended periods in the most unfashionable big city in Northern California (Sacramento); the desert edge of metro Los Angeles in Southern California; a small city with a small-town mentality in rural Georgia (the land that time forgot); the most ghastly (rich liberal part of Atlanta); and now in a pleasant city that's not nearly as tiresomely kneejerk liberal as its boosters and detractors would have us believe. I like not to be surrounded by people who insist I agree with them on everything, and who look to be offended, no matter their views. That’s gotten harder. But I think it might now get easier. Either way, I’m happy to chat with everyone who doesn’t shout at me.

And in my travels, I’ve also visited all 48 continental US states, many of them twice or much more, and not just when changing planes. (AND almost every year I travel through Britain in much the same way.) Always looking, always visiting museums and historic sites, and always chatting with people. Funny how so few road trip books and travelogues are by women. Steinbeck and I have had different experiences.

See? He got me to think I was reading about myself. Clever man. Great writer. Sadly, I will forever think like a historian, dedicated to highlighting what annoys my readers. But maybe Steinbeck did that, too.

Loved the map of John and Charley’s travels:

These quotes from Travels With Charley are John Steinbeck’s words,NOT MINE! He may say such things. I couldn’t possibly comment.

"When we get these thruways across the whole country...it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing."—John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley.

John Steinbeck absolutely loved America. His criticized what he loved, so he would have made a good Brit. But he was an American through and through, and that honesty has always been a tough sell in American culture, especially when people start to realize they agree, and fight back. Oddly enough, though, Steinbeck is still in print, so not falling on deaf ears. He never did.

You can probably now guess why the Steinbeck I’ve enjoyed most so far is Travels With Charley. I was thrilled to see that the NSC displays Steinbeck’s actual truck!! As ever, mouse over the photos to see bigger images:

And, in the end, I can only give a big thumbs up to Steinbeck’s final verdict on road trips:

Travels with Charley was published in 1960. Steinbeck’s final novel, published the following year, was The Winter of Our Discontent. It wasn’t well received in America, and critics also jeered when Steinbeck was awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature because of this book.

Even the Nobel Committee apparently didn’t think Steinbeck’s book was all that, and I wonder if he picked up on that lukewarm attitude? I think he did. Which is sad, because it was also a lifetime achievement award, although I don’t think he got that.

John Steinbeck never wrote another novel. Our loss.

The Winter of Our Discontent is just one of a big stack o’ Steinbecks now piled on my coffee table, which I’m working my way through. I’ve finished Once There Was A War and In Dubious Battle, and now I’m onto East of Eden.

That’s how I know the National Steinbeck Center worked for me. Hoosen said the same: We wanted to know more after we left.

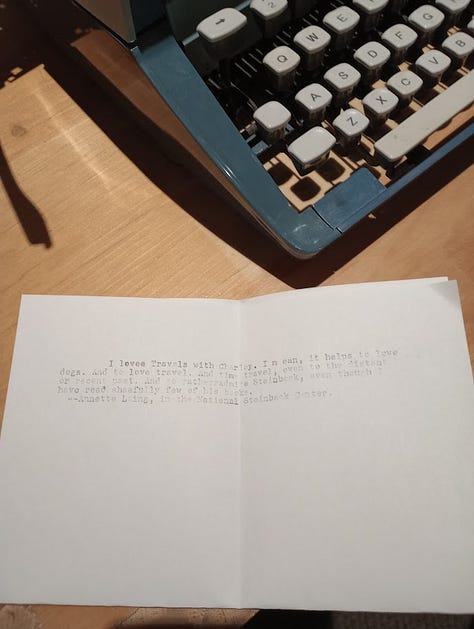

Before we left the National Steinbeck Center, I succumbed to temptation in the form of a typewriter at a desk which visitors are invited to use. Like most writers who long ago made the transition from typewriters to computers, I don’t miss them: Okay, yes, I miss the clack-clack ping zzzzz, and the smell of carbon paper, but otherwise, no. Still. My ego was attracted.

I don’t think the greatest writers of our or any day are in any danger from my stealing their thunder (transcript below photo):

The ribbon was a bit worn, so what I typed is faded, but here’s what I typed, or tried to, and please be kind, because it’s a first (and only) draft. How on earth did Steinbeck work so well without a computer and the multiple drafts and tweaks it makes possible? Wow.

I love Travels with Charley. I mean, it helps to love dogs. And time travel, even to the distant or recent past. And to rather admire Steinbeck, even though I have read shamefully few of his books.

— Annette Laing, in the National Steinbeck Center

Although he was put off novels by the attacks on his work in 1962, the year of his Nobel Prize, John Steinbeck kept on writing. In 1967, at the age of 64, he popped on a helmet and body armor in war-torn Vietnam, and spent a year writing from the front lines.

Steinbeck was a believer in the Vietnam war—no, he was not a Communist, not this man. He even got himself embedded as a writer in his soldier son’s unit, and took over machine-gun duty when the lads were tired. But as historians know, the times change faster than we do as individual people. Steinbeck’s support for the Vietnam War brought him more backlash by 1968, when the growing anti-war movement in an increasingly divided America accused him of being a warmonger. But by then, after a very 20th century lifetime of chain-smoking, Steinbeck was dying from heart disease. He died on December 20, 1968, at the age of 66, and was buried in a family plot in Salinas.

Once, there was a war.

Once, there was a great American writer.

His name was John Steinbeck.

P.S. Broken Men

Unlike most of the subheadings in this post, Broken Men is not the title of a Steinbeck book, but such men appeared in his books. Steinbeck himself? Unlike your average journo, I’ve tried very hard not to overstate my very limited knowledge of my subject. And unlike a news reporter, I put myself in the story, because that’s NBH: A historian bringing you with her, into books and places. That’s why this post, unlike the National Steinbeck Center, is not a reliable guide to the life and works of John Steinbeck. Rather, it’s my attempt to share with you the mental stimulation and inspiration I gained from the National Steinbeck Center.

As we left the parking garage in Salinas, at the first traffic light we came to, I spotted a disheveled man standing on the sidewalk, bent over, folded almost in half. He looked like a zombie waiting for a signal to move. “He’s on fentanyl, I think,” I said to Hoosen. I had read about the “fentanyl fold” somewhere, another horrific effect of that drug, and I don’t doubt I was right, but what use is that, being right, and from inside a safe car? To see a human being in distress, and have my only response be curiosity, what kind of humanity is that? John Steinbeck would have given me a hard time, maybe. Maybe not. Writers are human.

In WWII, as we saw, John Steinbeck abandoned his observer role to fight for his country. Steinbeck’s vocation, his mission, in life was not passivity. He was not present simply to take notes, but to be present with every sense, to interpret, to hold up a mirror angled in his own image. He was an observer all his life, it seems, from his hanging out watching card games in Salinas, to driving around America in his later years, to manning a machinegun in Vietnam. He was no ideologue, no believer in any political straitjacket, and he was cynical about those who were. But there was nothing passive about him. He saw value in action, his own, and others.

What would John Steinbeck have made of his museum? What would he have made of homeless encampments everywhere in America, filled with broken people, for whom invisibility and contempt are their lot as the public grows exhausted and frightened by their sheer numbers and presence? What would he tell us about America now? I have no idea. If I could bring him back from the dead, I simply don’t know what he would say, and would anybody listen? Or would critics attack him now as they did then, as an extremist?

Controversial doesn’t mean untrue, no matter where we’re talking on the political spectrum. Eleanor Roosevelt defended Grapes of Wrath after touring a migrant camp. Asked by a reporter if she thought Grapes had exaggerated, she said firmly that she had never thought it had. Facts support her.

But John Steinbeck and Eleanor Roosevelt are in the grave, and the world they inhabited, and that Steinbeck interpreted, is gone. He leaves behind his books, available in every library, for us to read. If we still read. Nothing stopping us: The more books we read, the better our reading gets. Once you have the basic skills, and most people do, it’s a matter of will.

Did the National Steinbeck Center work for us? Absolutely.

Would the NSC work for you? It might—but we are all different, despite the reading conformity encouraged by book clubs, must-read lists, bucket lists, and all the bandwagon stuff I can’t stand. However, Salinas is only half an hour’s drive from the more attractive Monterey (home to the cleaned-up Cannery Row). Hint.

Coming soon for paid subscribers at Non-Boring History, we’ll meet England’s shortest-ever King. He got that way when his head was amputated by his own people. What did he do to deserve such a fate? Academic historians almost come to fistfights over that.

And coming next?

NBH Online Sip ‘n Chat!

Sunday, July 20, 2025

Duration: One hour

Start Time:

1 p.m. Eastern

12 Noon Central

10 a.m. Pacific

6 p.m. GMT (UK)

No matter where you are in the world, here's a chance to hang out with me and other Non-Boring History readers!

Our theme: Historical Travel (mine and yours!) I'll share stories and pictures to get us started, but feel free to bring questions, stories from your own historical travels, or (for the very shy) yourself and something to sip on! It's a friendly bunch, so fear not!

This event is exclusively for paid subscribers. Join us today, email me by hitting reply afterward, and you will get an invite!

Already a Nonnie (paying subscriber)? Email me at the usual address, or hit reply to this email, and I'll send you the Zoom link!

Once again, lengthy but fascinating

Thanks Annette

I didn't happen to read The Grapes of Wrath until my early forties. I don't think that I would have understood it as well when I was younger. It was one of the several famous books my education had missed (and I had a good education) that summer. I'd like to read more of his works, but there are so many books and I have so few years left. The two most dangerous places for me are libraries and bookstores. Maybe the afterlife for me is a comfy chair, a nice drink, and unlimited reading.