The Free Love Commune That Sold Out (2)

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Continuing the story of Christian socialists who traded the promise of heaven on earth for silver. Or did they?

How Long Is This Post? 7,000 words, about 32 minutes.

This is the second and final part of my Annette on the Road post on the Oneida Community in Upstate New York. Read Part 1 here: The Free Love Commune That Sold Out (1).

Victorian Socialists who formed a utopian community, aiming for human perfection, and practiced free love? It sounds too good to be true! And of course it was. The experiment ended after more than thirty years, I suggested in Part 1, because its leader, finding his views on sex out of step with the times, fled to Canada to dodge charges of statutory rape. So endeth the Oneida Community.

But, of course, that’s waaay too tidy to be history! The story of the Oneida Community is much more complicated, much more interesting, and, in fact, much more amazing! Look, what we think of as a “deep dive” at Non-Boring History is actually the picture book version as far as the experts are concerned.

I'm a historian, but on this, I'm no expert. Dr. Thomas A. Guiler, however, is. Tom is Director of Museum Affairs for the non-profit that owns and preserves the former home of the Oneida Community, which is a National Historic Landmark. He’s also an expert on 19th century American Utopian communities, and Oneida in particular. I met him at the Oneida Mansion House, and after we exchanged the funny handshake we reserve for fellow members of the academic historian fraternity, I kicked off the conversation with a breezy “So, John Humphrey Noyes. Bit of a perv?”

And Tom did the historian sigh that I know all too well from when I don’t even know where to start when I get a question like that from a member of the public. But I wasn’t there to flaunt my opinions. I was there to learn. I’m a historian, sure. But I’m an early Americanist, and even if I do know quite a bit about the Puritans, and other Utopian movements in colonial America, I know (as I already confessed) very little about 19th century Utopian movements. I now know a lot more than I did before visiting Oneida. If I blew it, I’m sure an email will shortly wing its way from Tom Guiler's office in the Oneida Mansion in Upstate New York.

So that’s why we’re here today! To talk about what happened next. Friends, it’s gobsmacking. And it doesn’t end with John Humphrey Noyes hurriedly packing his bags and hailing a cab for the Canadian border.

So let’s return to the Oneida Community. Yes, we’re going to be talking about the “S” word. That’s right . . . We’re talking . . .

SOCIALISM {dramatic horror music}.

Yeah, sorry, I get you're disappointed. Nope, we already talked enough (maybe too much) about Sex in Part 1. There will now be a short pause while readers who missed Part 1, and figured they would just skip it today, scramble to find it. Here’s the link again, folks.

But don’t think Part 2 is where the story gets all boring and academic! Here’s your hint: I’m going to liven up Thanksgiving for you! You will tell everyone around the table how Grandma’s cherished silverware was the work of a Christian socialist free love commune! If that doesn't make Uncle Joe choke on his turkey, I don't know what will. See? Another benefit! Shutting up Uncle Joe’s monologue about how people these days don’t want to work anymore!

Ooh, The Socialism! 😱

A historian I used to know, an expert in the history of the Catholic Church, was regularly faced with classrooms full of skeptical Southern Baptists, Pentecostalists, etc, etc, who had been brought up to believe that only their faith was “correct”. She told them that Christianity basically came down to belief in the Holy Trinity. I’m not sure that the Unitarians would have bought that though. So let me suggest that, for the purposes of writing history (not theology), my working definition: Do people have faith in Christ’s divinity? Do they call themselves Christian? Okay, they’re Christian. To do anything else is to try to act as God’s screening committee of one, and I’m not prepared to do that. So be assured: The Oneida Community were Christian. They held Bible Studies, Sunday schools, sermons, the works. John Humphrey Noyes frequently gathered his followers in the big hall, and gave sermons, which he called “Home Talks”. He was convinced that he and the Oneida Community were following God’s will.

Okay, everyone. Prepare the smelling salts for our conservative Nonnies. Stand by to catch them. Conservative Nonnies? Steel yourself with your renowned grit.

I grew up in a New Town (a socialist experiment) in a democratic and mildly socialist Britain in the 70s. I never heard a soul—not even my Conservative Party-voting, stern Victorian Posher Grandad in Scotland- object to quality state (public) education, the National Health Service, or the affordable high quality public housing in which his son’s family lived.

Posher Grandad was a Presbyterian elder, head of the engineering department at a local college, and basically a Victorian patriarch. He objected to Young People who weren’t his grandchildren (and he wasn’t sure about us, either), and disapproved of American gun culture. Most of all, he was agog that Americans didn’t have socialized medicine. I wish I could introduce you to Posher Grandad. Sadly, he checked out when I was in my late 20s, but not before I could get to know him as an adult, and what a delightful man he was. He even taught me to drink whisky.

Growing up in this cesspool of Brit socialism with all that “free stuff” never stifled my fierce ambition, either. Substacker Mike Sowden (Everything is Amazing) recently described me as the hardest-working person on Substack, so I think we can rule out lazy, too. I’m always a bit puzzled when I hear that socialism makes people lazy.

Hold it! Step away from the comments section! I'm not starting a debate. I'm explaining why, thanks to my life experience, I am not surprised by how Christian socialism (yes, a thing) played out in the Oneida Community. I'll make things clearer as we go.

Socialism (or communism as the Oneidas also called it, without any reference to Karl Marx, because these two words cover a lot of variations, hence lots of confusion) certainly didn’t cause an outbreak of laziness in the Oneida Community. The Community made work enjoyable, allowing people to choose the work they wanted to do, and valuing everyone’s work, which lifted all moods. They also toiled together on chores, in “bees”, so even if the work itself was boring, at least they got a little party out of it.

Look, the Community wouldn't have survived for long if they'd all sat on their butts. They had an enormous mansion and dozens of kids to support.

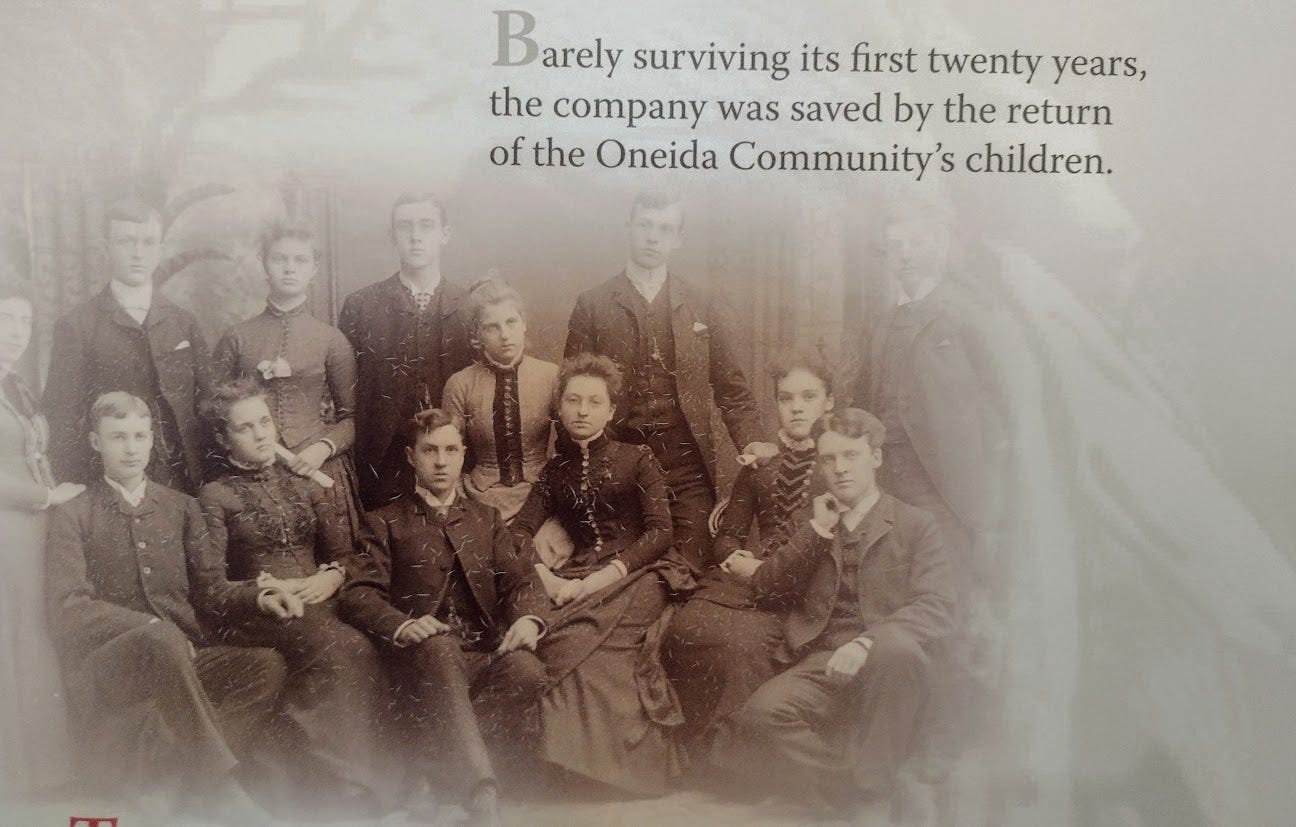

We already saw how the Oneida Community welcomed tourists, curious folks who came to gawk at them, and how they promoted tourism. And they were always interested when a “family” member came up with ideas for new products, more efficient ways of making the things they already produced, or new ideas for keeping visitors entertained, like croquet, and Virtual Reality viewers.

Allowing community members to be creative entrepreneurs yielded massive dividends. Look, the most talented creatives aren’t primarily motivated by money, but by love of what they do, and all they need is enough support to allow them to do it.

That was my friendly request that you become a Nonnie (paid subscriber) to Non-Boring History if you’re not one already.

At the Oneida Community, creativity yielded happiness and respect. Among the members of the Community was inventor Sewell Newhouse, son of a blacksmith, who developed a new kind of animal trap.

Sorry, vegans! Hunting was still common and necessary for millions in the 1860s and 1870s, for food, clothing, and pest control. Newhouse loved to tinker and experiment with devices to catch all sorts of critters. Joining the Oneida Community gave him the time, equipment, and supplies to invent to his heart’s content, and lovingly craft his self-designed artisanal traps by hand.

Oneida traps were amazing. Orders poured in, and soon, the Oneida Community needed to turn to mass production of Newhouse's inventions. They built a factory, and hired workers to meet demand for their now world-famous traps, which were used from Oneida to Russia. That's right! The Oneidas were successful manufacturers with a global customer base, and they were Christian socialists!

Head spinning yet?

So what went wrong? Well, in most ways, nothing did. The Oneida Community, as we have seen it, ended, but it didn't fail. Nor did it end with the flight of leader John Humphrey Noyes to Canada. The explanation, as ever in history, comes down to multiple causes, not just one.

It was now 1880. In many ways, the Community became a victim of its own success. There were only 200 people in the Community in 1880. Even though they hired local help to work in the factory, the manufacturing of traps and silk thread alone took increasing amounts of members’ attention.

All was not well in the Mansion. “Complex marriage” felt a bit incestuous to younger members of the community: It must have been a teensy bit weird to contemplate sex with someone you had always seen as a parental figure. Anyway, the young adults just wanted to, you know, get married to an age-appropriate person and have kids, just like other middle-class Americans. Noyes's letter disavowing complex marriage gave them the green light.

But that’s not all. Young folk also wanted their own homes. Their own stuff. Like other middle-class Americans.

Now, you’ll notice our conservative Nonnies are reviving, thanks to the ministrations of Hillary Clinton Nonnies and Bernie Sanders Nonnies, who are taking turns wafting smelling salts under their noses! And they are smiling wanly. Of course the young Oneidans saw the light! they mutter. Free enterprise beats socialism! Always! Ah, no. That's not how it happened.

The real agent of change wasn't a shift in ideology. It was a shift in generation. The never-ending change that is American culture. The reliable thing about young Americans is that they want to do things differently from the ‘rents.

By the end of the 1870s, younger Oneida Community members had become more secular in outlook than their elders, so the religious priorities of the community didn't really float their boats. Plus, as Noyes aged, it wasn't clear who would take over. His son Theodore was his designated successor, but Theodore was neither charismatic nor enthusiastic, and his status as heir apparent was challenged. There were squabbles. At the end of August, 1880, the Community voted 199-1 to end the commune. Some left for elsewhere, including southern California. There, former Oneida Community members helped found Orange County, which went on to become a place so conservative that its airport is named for John Wayne.

The end of the commune was less to do with socialism v. capitalism than with the usual problem of utopian communities, holding folks together after the first excited generation. I mean, my own childhood postwar state socialist Utopia gave way to Margaret Thatcher's revolution. It happens. Utopian communities that survive for the long haul do so by letting dissenters go, and by moving with the times. Even the Old Order Amish have proven canny in their adoption of technology. Last time I bought something from my favorite Amish quilt shop in Pennsylvania, the Amishman behind the counter casually pulled out a wired credit card machine.

Most Oneidans didn’t leave in 1880. They stayed put. They kept the Mansion, dividing the single rooms into private apartments. They divided up the furniture. They owned stock in the new company they formed. The Oneida Community survived because they didn’t just tolerate change. They rolled with it. They even embraced it.

They converted themselves into a corporation. Realizing that hunting was now in decline, and demand for traps with it, they had already started producing high-quality silverware. Just like Grandma's.

But they did not want to give up what they cherished most: Community.

And they never did.

The Return of the Stirpicults

We were descendants of Oneida Perfectionists and were attempting to carry into a modern setting as much of the principles taught by our forebears as seemed to us practicable. -Pierrepont B. Noyes, President, Oneida Community, Ltd.

Big business was the way forward in the early 20th century: Massive companies like General Electric. Company towns. How would little Oneida Community, Ltd survive and keep to its core value of community?

After the Community dissolved as a commune in 1880, the members reconstituted themselves as a joint-stock company, like a corporation. They now worked to bridge the gap between their communal ideals, and the modern business world. It was tough going. Older members of the community found they had to pivot to a rapidly-changing American business climate. By the last decade of the 19th century, they were barely staying in the black, thanks to their reputation for traps and silk. The quality of their silverware, their newest, most modern product, was failing.

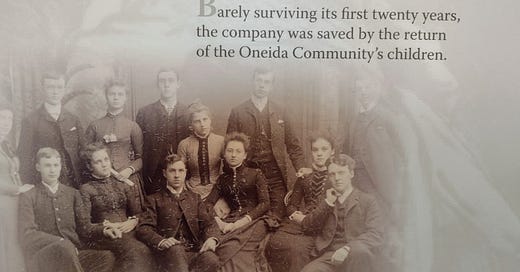

Enter the “Stirpicults”. These were the children of the Oneida Community, the products of “complex marriage” and an early program of eugenics, or selective breeding, which I wrote about in Part 1. Their return ensured that the Oneida Community, Ltd. would not only survive, but thrive as a business.

Pierrepont B. Noyes, one of John Humphrey Noyes’s stirpicult sons, had already created a thriving silverware business after leaving the community. Now, in 1895, he assumed leadership of the company, and he would stay involved until the middle of the 20th century. Noyes and six other stirpicult sons, now led the way.

Stirpicult women also continued to support the community, among them textile artist Jessie Kinsley, whose work is on display throughout the Mansion museum. She explained that her Stirpicult brothers balanced “desire for riches and desire to help others.” She also wrote:

“Thus it will be seen that a corporation is not necessarily the soulless creature it is sometimes represented as being. It may be permeated by personality, the conservator of fine traditions, animated by high ideals, and possessed of the ‘commercial imagination’ which altogether impart to its undertaking elements of pleasure and wholeheartedness like that which animates the craftsman who sings while he works.”

The Oneidas remained a community, and they remained about more than making money. They were committed to manufacturing good-quality merchandise, even if it cost more. They were fiercely competitive, and modern in their efficient new methods. But they were not ruthless with their employees. High wages. Shorter work days. Good benefits. Sharing profits. And they also gave back to the town, supporting community organizations and facilities. Some employees as well as elderly Oneidans lived in new apartments in the Mansion House, and there was a waiting list: Low rents, excellent facilities (laundry, library, Turkish baths, later tennis and golf) made the Mansion House a popular place to live. Still, many members, from the break-up on, built houses in town. Those who could afford to built houses designed by architects, among whom was stirpicult Theodore H. Skinner, who followed the Arts and Crafts movement, prizing artisanal craftsmanship over industrial mass production. Doesn’t that make sense?

Poorer people, including employees, lived in plain old mass produced houses. Sherrill, the company town, while supported by and reliant on the Company, was independent of it. But the Mansion House remained a community as well as company center, hosting speakers like Booker T. Washington and H.G. Wells, concerts, July 4th gatherings, weddings, and much more. There were clubs for employees, dances, games. This was not socialism. It was welfare capitalism. But for employees, whatever you called it, it was great. And the Oneida Community led the way. They were incredibly successful: There were even Oneida factories around the world, including one in England, at Sheffield, then famous for its cutlery.

No “happy ever after” though. As decades went on, things kept changing. When Oneida, Ltd (as it then was) finally shut up shop in the 21st century, it was a decrepit shadow of what it had been: Done in by competition from cheap silverware from Asian manufacturers, by changing tastes that valued price over quality, it was bought by a corporation that promised not to close the factory, but did it anyway. The impact on Sherrill, on the larger community, was, in the words of several people I spoke with, “devastating.” One person mentioned “golden parachutes” for executives, while workers with decades of service lost their pensions and healthcare plans. Devastating, indeed.

They’re Still Here

I was only at the Oneida Mansion House for a short time, but even so, I could tell before I asked that this place was something more than a museum that rented hotel rooms. Working in the lounge, I watched people come through who clearly were neither tourists nor staff. One older woman stopped by to have a cheery chat with the facilities manager, whose office is off the common area. Others greeted me with welcoming smiles. There was a bank of mailboxes. A bulletin board, on which someone had tacked a flyer about the death of a woman who had clearly had a full life, in California, I think, as an artist and activist.

And that’s when I thought to ask. Yes, people still live here. You can too, if you like: There are apartments for short-term and long-term rent. Some of the residents are Oneida Community descendants. Descendants sit on the board of the non-profit that owns and maintains the Mansion and museum.

Before you pack your bags and put your house up for sale: This is no longer a commune. “Complex marriage” ended a hundred and forty years ago. But there is still a little community of sorts here. And the Oneida Mansion still advertises to attract curious tourists for visits, tours, and stays. And, yes, they have a terrific book and gift shop, where you can spend more money to support the upkeep of the Mansion. Because of course they do.

But Wait, There’s More!

I had a fascinating chat with Dr. Tom Guiler while Hoosen and I were staying at the Oneida Mansion, and I have since had the pleasure of talking with him on ye olde Zoom, and it was fascinating. Here’s our chat, and an edited transcript, in which Tom throws more light on the Oneida Community. This is a special bonus for Nonnies, paid subscribers to Non-Boring History.