Selling My Religion: Shopping and the Preacher (2)

ANNETTE TELLS TALES How George Whitefield Sold His Religion. Pay Especially Close Attention if You're in Business.

Continued from:

Selling My Religion: Shopping and the Preacher (1)

·

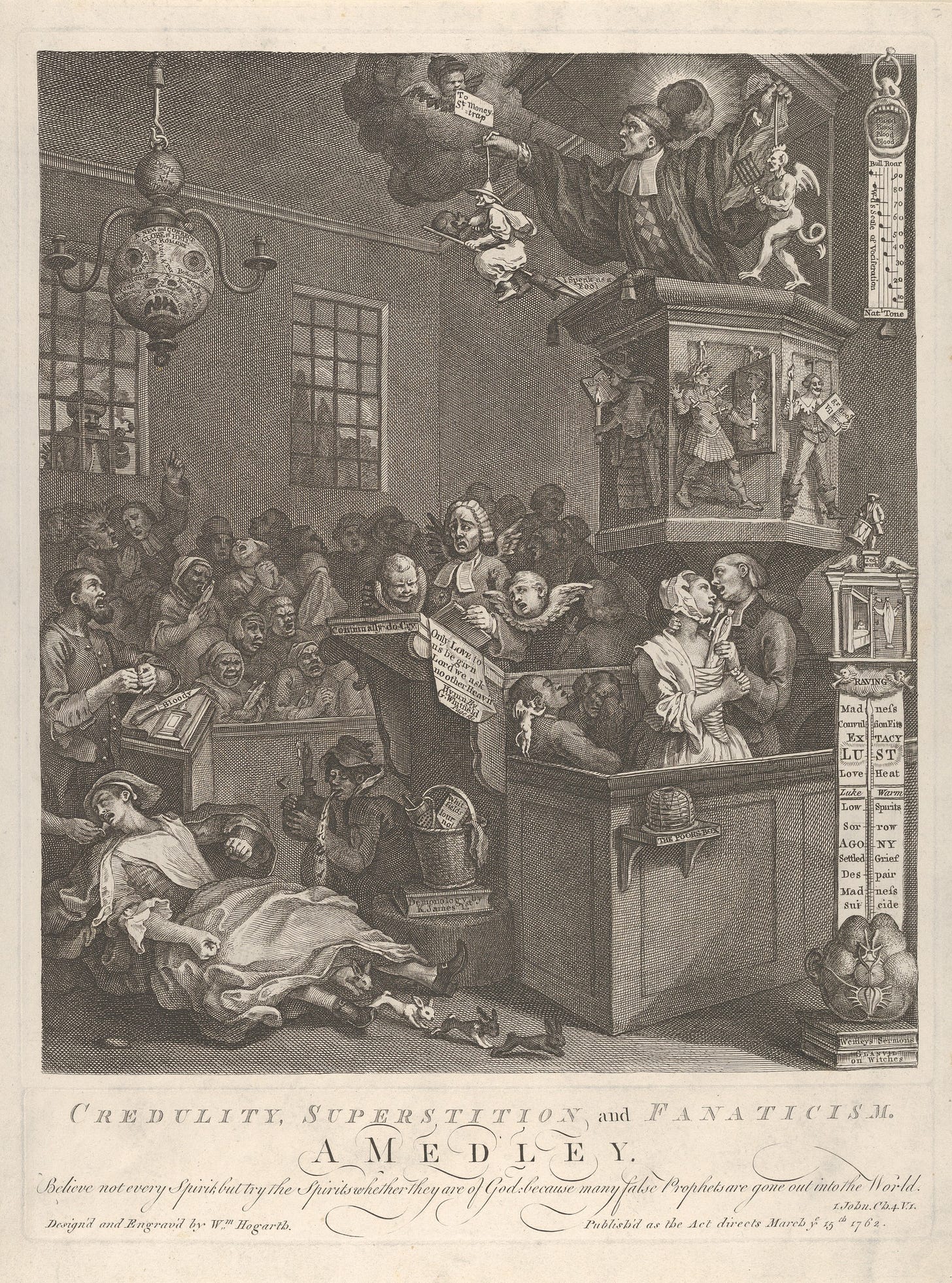

Shopping takes off in the 18th century! Born into that world of luxuries for sale is George Whitefield, innkeepers' and wine merchants' son and brother, who grows up in the family businesses, picking up tips about management, publicity, retailing, and transatlantic trade. He will go on to apply everything he learned to his life's true calling: Selling his own version of Christianity, in Britain and America. Watch as he becomes a transatlantic sensation, a TV preacher before TV, who makes his greatest impact in . . . print. That's what we'll talk about today, when I continue my riff on historian Frank Lambert's "Pedlar in Divinity”: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals (1994)