Reading -- The Room

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Legendary place of reading and thinking, plus Annette's uniquely grumpy takes on the British Museum and London

Note from Annette

Renegade historian Dr. Annette Laing writes Non-Boring History on a variety of subjects in American and British history, in a variety of styles, including rewriting academic history into chatty and entertaining posts, and reports and reflections from her historical travels, like this.

If you’re a Nonnie, a paying reader, you’ll see a link above the photo to my readaloud of this post. Thank you for supporting Non-Boring History.

Not a Nonnie? Please do your bit:

London: A Curmudgeon’s View

Okay, finally getting back on my feet here in Madison, Wisconsin, after screwing up my knees during a month in my native UK, which is what happens when you go from comfy living-is-easy America to stairs, stairs everywhere, without ramping up exercise in advance. In short, I’m very happy to be back, despite all the long faces around me. Did I miss anything while I was gone? Perhaps best not to ask! Ahem.

Please don’t be jealous because I spent four weeks in Britain. I’m British, after all, and grew up mostly in a working-class town about thirty miles from London, so for me this wasn’t an exotic trip so much as it was a bit like spending a month touring Ohio.

I regret to say that I find even London losing its charms, and I don’t think this is just because I’m getting older. London is becoming every other city, divided between extremely rich and everyone else. Back when I stayed with a British friend in posh Kensington in the early 90s, a launderette (laundromat) and two convenience stores were across the street to serve local residents, most of whom were wealthy by the standards of the time. If you wanted to buy your own washer/dryer, or have a bigger choice of food for a price, and posh groceries too, then down the street was the fantastic Harrods department store, and its Food Halls (meaning retail groceries, not varied eateries). The sight of Harrods’ amazing artistic display of dead fish alone was worth popping in for. The fabulous cheese counter offered friendly and knowledgeable service, and a vast and varied selection of tempting cheeses I could afford, so long as the sliver was small enough. I remember how sweet the cheesemonger was when I asked how small, exactly, was a minimum portion.

Now? Not so much. Uber-rich oligarchs who stop by their “homes” maybe for a week or two each year with a retinue of servants, don’t need launderettes, convenience stores, or, for that matter, a browse round Harrods, and its Food Halls.

Yes, London is becoming like most Western cities: The same as other Western cities. Even Harrods, once eccentrically British, and even though it has thrived in an age of obscene wealth to which it’s happy to cater, now shows the loss: On the ground floor of this enormous building, the jewelry department in 2024 is arranged more like a very walkable version of Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, or Buckhead in Atlanta, or any uberwealthy shopping street in the world: Instead of walking or driving down streets, you promenade through aisles in which all the shops on either side of you are the same size and shape and layout. They’re distinguished only by the names above the doors: Cartier. Hermes . . . (yawn). The usual boring names that people buy to convince the rest of us that they’re important rather than deeply dull. And it works, doesn’t it? We prefer to support Known Names in every sphere. This week, I read about how many (most?) celebrity books for kids are written by ghost writers, but the public doesn’t care, so long as the brand is right. Soon, it will be AI doing the heavy lifting, and we really will divide between those readers who want to read the work of real people, and the majority, who won’t care, so long as they feel part of the in crowd.

In Harrods’ jewelry department, a solitary salesgirl stands by hopefully at each branded shop entrance as we impudent tourists stroll by, wisely ignoring the temptation to try to browse, because at some point, we would have to fake dissatisfaction with the merchandise, or arrange for a second mortgage, or worse.

But not Annette! Nope, I’m actually here in Harrods to make a purchase!

Cheese! Harrods’ cheese counter, always so vast, so varied. Except that now it’s more like a cheese nook, and I stare at it in dismay. I can immediately think of better (and likely cheaper) places in London, even in Madison, to buy cheese, so I don’t bother.

But look! Harrods now has a massive Chocolate Room! Near the entrance, a young man dips out-of-season strawberries into melted chocolate, which we could then buy in little cones. Like I’ve never seen dipped strawberries, or am under any illusion that his work is an advanced example of chocolatier talent: The chocolate is assuredly made elsewhere. Around the walls of the Chocolate Room, the labels from various expensive but familiar and mediocre Big Chocolate factory companies also tell a story, of soulless mass production. Again, I think of Madison, where earnest chocolatiers make everything possible by hand. Again, I take a pass.

I’ve never been a proper shopper in Harrods (or Horrids, as Brits sometimes call it, in classic Brit style). I’m a window shopper, needless to say. But back in the day, like in the early 90s, I enjoyed touring the store’s over-the-top Food Halls and making very modest purchases. Not anymore. I’m done here. No reason to return.

Grump.

Look, Samuel Johnson, chatty author of the first quality English dictionary, once claimed that if you’re tired of London, you’re tired of life, and all my life, I bought that. Now? Whatevs. I no longer care what the long-dead Dr. Johnson has to say. Spare me crowds, even in November, and pickpockets (they lifted my rain jacket out of Hoosen’s backpack in the tacky shopping neighborhood of Oxford Street—and we were only passing through to get to the train station). Spare me the general miserable feeling that all is not well, and this time, my fellow Brits may have a point in their grumpiness.

But hey, don’t let me put you off visiting the UK, international friends! The tourist experience is always different from the natives’, not least because it’s all so new and exciting, and also because travelling from castle to manor house to palace in temperature-controlled luxury coach driven by old bald bespectacled bloke in shirtsleeves and tie (they always look like that, I swear) is a pleasant way to see Britain. I’m not gonna do that, though, because I have seen all the things at my own pace. Plus I am old, British, and bored.

Just ignore me. Fork over your generous donation to the national economy, and Brits will happily show you more old buildings than you can handle from the comfort of your luxury bus (loos on board).

Armchair traveler? Don’t miss a thing! Become a Nonnie, a monthly, annual, or patron-level subscriber, sign up to get postcards and other mail, and we might even meet for coffee on my travels! You’re connecting with a writer not a robot, a person not a platform. And if you’ve been on the fence, tis the season of giving!

Museuming in the Mother of All Museums

Rare though this is for me, I was drawn to the British Museum a couple of weeks ago. That’s because it just opened a temporary exhibition called Silk Roads (I’ll write about it in another post).

It takes a lot to get me through the doors of the British Museum.

Wait, what? Laing, what are you talking about?

I know, I know. My reluctance is unfathomable to most of my North American readers, but, hey, have you ever been to see the stunning natural wonders of Utah? No? That’s really sad! You’re missing out!

See, I always get a crushing, overwhelming feeling of dread as I cross the British Museum’s massive and imposing forecourt.

I am now imagining all of you looking at me like I’m bonkers. But, again, I’m not truly a tourist, not someone excited to see Britain’s global treasures, many of them nicked from the finest corners of the world, for the very first time, in the world’s first public museum (founded 1753, after much discussion of whether the nation really wanted to take on uber-nerd Hans Sloane’s collections of random crap). Why my lack of enthusiasm? Like every kid of my era in southeast England, I have British Museum memories, almost none of them good:

Turning up with my dad, all excited to see the stunning Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972, only to find that everyone else in the UK had beaten us to it. I recall an epic line of thousands of people snaking tightly back and forth across the vast Museum forecourt, going out the gates, and right round the building and probably to infinity and beyond. Brits had got used to massive queues during the War (which was, stunningly, less than thirty years earlier) .Dad and I were not so patient. We glanced at each other, and mutually decided not to bother. I finally saw the Tutankhamun exhibition nearly a decade later, catching up with it on a school trip in Hamburg, Germany, so I didn’t miss out. Meanwhile, back in 1972, as a consolation prize, Dad and I popped into a nearby shop, where he bought me a Tutankhamun Jackdaw: Jackdaws were (are?) folders of replica historical documents and information, aimed at kids with interests. Tutankhamun was my first Jackdaw, and it was awesome. I pinned up everything from it on the wall in my room. And so Annette curated her first museum exhibition at the age of seven. Trip to the British Museum? Disappointing, but not a total loss.

Pretty much a total loss were all British Museum school trips, mine and everyone else’s (I refer you to Sue Townsend’s classic comic novel The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole age 13 3/4 for a hysterical fictional version of a school trip to the British Museum, which is hardly fictional at all). We British kids in those days were let loose in the Museum to see whatever we wanted to see in the two miles of exhibition space covering nearly a million square feet. This often resulted in mayhem. When we were 16, my school group, led by the brave Mrs. Crewe, was no longer interested in creating havoc in the British Museum. We waited until Mrs. Crewe was out of sight, and then retreated to the cafeteria (a grim but wonderfully affordable place in those days). We sipped tea and smoked cigarettes, safe in the knowledge that Mrs. Crewe was very unlikely to find us in that vast building. She didn’t. Mind you, this taught me (1) Never give students free rein in a large museum for a long period without any kind of accountability and (2) If they do scarper, look in the pub/cafe first. Now I think of it, maybe Mrs. Crewe was in the Museum Tavern, the pub across the street? I’m not kidding. That’s brilliant! I bet she was.

I brought my own students to the British Museum in 2007, as the kick off to my class in museum appreciation. I gave them just 15 minutes to do a quick explore (!), and then return to me in the Great Court, the center of the museum you see above, and give me a one-sentence explanation of what the Museum was about. I didn’t push my luck with them.

Of course, I brought my son Hoosen, Jr. here at a suitable age to see Egyptian mummies and whatnot, which he suitably appreciated, before we quickly abandoned ship: I’m not kidding: Never spend long in the British Museum, it’s like a messy tsunami of overstimulation.

Last time I was here was again with Hoosen, Jr., now a teen, for a temporary exhibition on the drawings of John White, the artist who accompanied the first voyage that settled Roanoke, England’s first attempt at an American colony, a scientific exploration/colonization effort that didn’t end well for those involved, but makes a great story. Hoosen, Jr. gamely appreciated the display of White’s drawings, but this visit was for me: The chance to see White’s drawings was irresistible, not least because they hadn’t been on show since the year I was born, and I doubt will be shown again in my lifetime. Those wonderful figures of Indians, made to look as attractive and relatable as possible to the English public! These were less art than they were pro-colonization propaganda. The modern age had truly begun.

The Ministry of Many Truths

On Saturday, in a post for Nonnies (supporting readers), I wrote about a brief stop by George Orwell’s Ministry of Truth from his novel 1984.

Join us as a paying subscriber today for access to every post, including nearly 500 of historian Dr. Annette Laing’s entertaining and varied pieces at the Non-Boring History website. Historical literacy never felt so good. And people can’t live on punditry, just saying.

Take a look at the photo from the British Museum at the top of this post. What an odd set-up! We see a great round building plopped in the center of the Museum, like a bullseye. This makes more sense once we realize that this area was once a courtyard, open to the skies, and empty until a long-ago bright spark had the idea of using the empty space for a great purpose, that round building.

The round building is the famous Round Reading Room of the British Library. The Library was originally known as the British Museum Library. That’s because making books available to the public was part of the Museum’s mission from the start in 1753, the start of public libraries in Britain. And that’s because Hans Sloane, the nerdy collector whose stuff formed the basis for the British Museum, the world’s first public museum, had included his books in his generous donation, alongside stuffed giraffes, ancient pots, etc. Soon, the British Museum Library’s collections were expanded by other donations, including the personal library of King George “I lost America” III. And it wasn’t just books that the British Library accepted: Archives of the papers of famous Brits came to be stored here, like nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, computer pioneer Charles Babbage, and prime minister pioneer W.E. Gladstone.

No wonder the British Library was so popular that it began running out of room for readers in its first century. Within a hundred years, more room was needed. Enter the Round Reading Room! It took three years to build, and it opened in 1857. The Round Reading Room was plunked right in the British Museum’s courtyard. That setting and the Reading Room’s very cool design were both the brainchildren of an Italian.

An Italian? Oh, yes. Because London has long been an international city, and it has long opened its doors to exiled thinkers.

Sir Antonio (Anthony) Panizzi left Italy to avoid arrest as a revolutionary. He moved to Britain, because Britain and the US have long served as the world’s tolerance centers in modern history. And before you say anything, both countries have always had a mixed record on free speech, but they were and are still better than what political dissidents left behind.

Panizzi moved to London where he was hired as a professor at the University of London. He also became a librarian at the British (Museum) Library, but I don’t get the impression he reshelved books from a cart, or anything like that. He was an ideas man. He vastly improved the collection by doing things like, um, ordering a lot more books, and making scientific research more available to the public (rather than hidden in university libraries). He then designed for his adopted nation this simply awesome space for research. I mean, how cool is this? This is not to say Panizzi was always popular: Many Brits did object to a (gasp!) Italian having so much power at the British Library. And after he quarreled with historian Thomas Carlyle, Panizzi pettily refused to let him have a private research room. End result? Carlyle founded the London Library, which was, and remains, a private club.

But, unlike Carlyle, most people weren’t in a position to start their own library, and were happy to have access to the impressive book collection at the British Library. Here, in the Round Reading Room, readers famous and obscure came to soak up knowledge, process it, and develop ideas of their own. And what a variety of ideas they had.

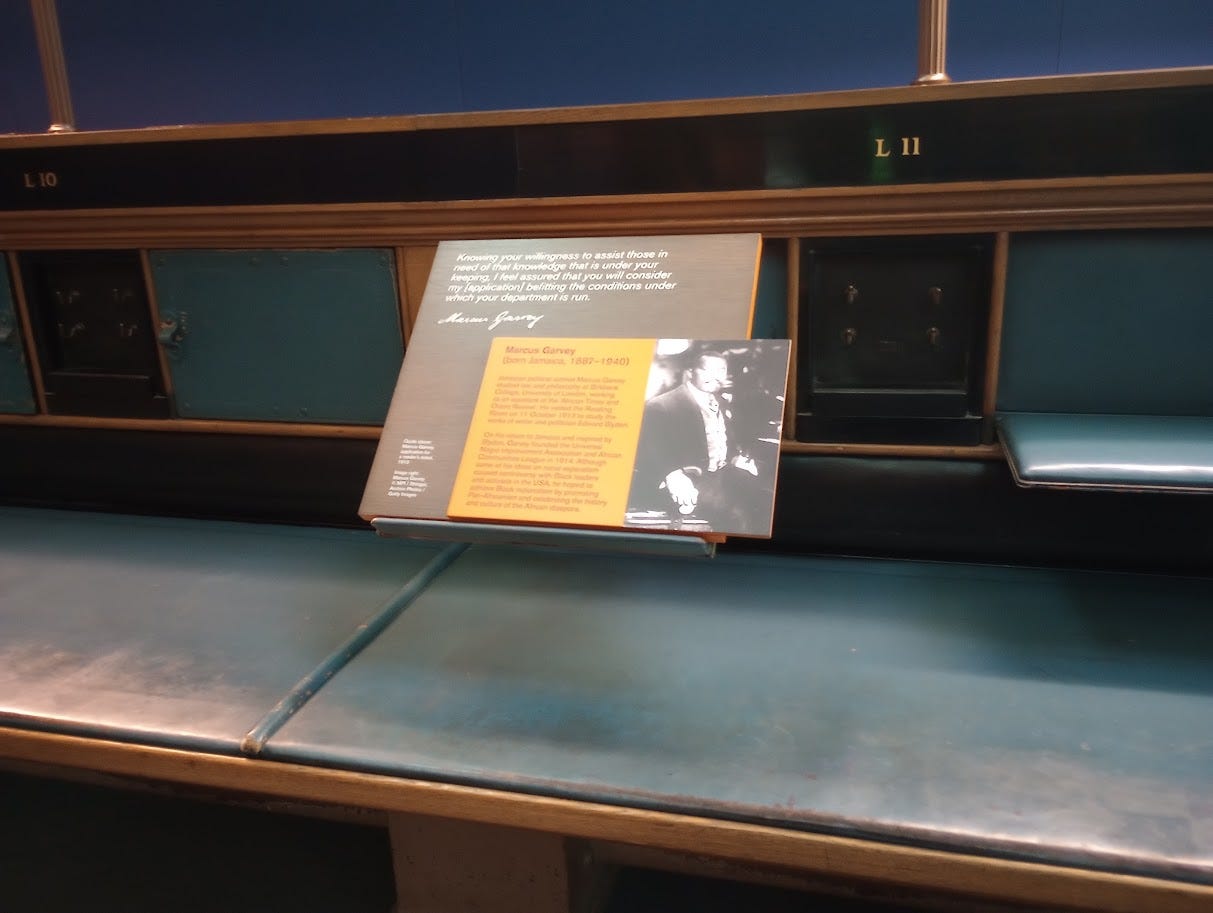

Marcus Garvey, Jamaican-born scholar, studied law and philosophy at the University of London in the early 20th century, and in October, 1913, he popped into the British Library to read the published works of Edward Blyden.

Like Marcus Garvey, Edward Blyden was from the West Indies, where he was born into a free black family. Hoping for opportunity denied him during a residency in the US, where he encountered the usual knuckleheaded racial discrimination, Blyden emigrated to Liberia, an American colony in West Africa founded for formerly enslaved people.

Blyden wrote about pan-Africanism, which holds that people of African descent everywhere share a common identity and cause: He studied the Jewish diaspora, and even visited Jerusalem, believing that Zionism, aimed at developing a Jewish homeland, was a good model for black people around the world. In 1860, Blyden corresponded with British politician W.E. Gladstone, who invited him to study in Britain, but he decided to stay on as a professor in Liberia.

Ironically, Liberia was dominated by people of American descent, who essentially colonized and discriminated against the native people of the area, but that’s a long story for another day. Meanwhile, the writings of Edward Blyden had a big impact on Marcus Garvey, who pushed pan-Africanism in the US, where many black working-class people were drawn to his idea of moving to Africa (can’t blame them when you consider that this was the era of Jim Crow and lynchings), while most civil rights activists were generally not so keen—understandable since, after all, they were Americans.

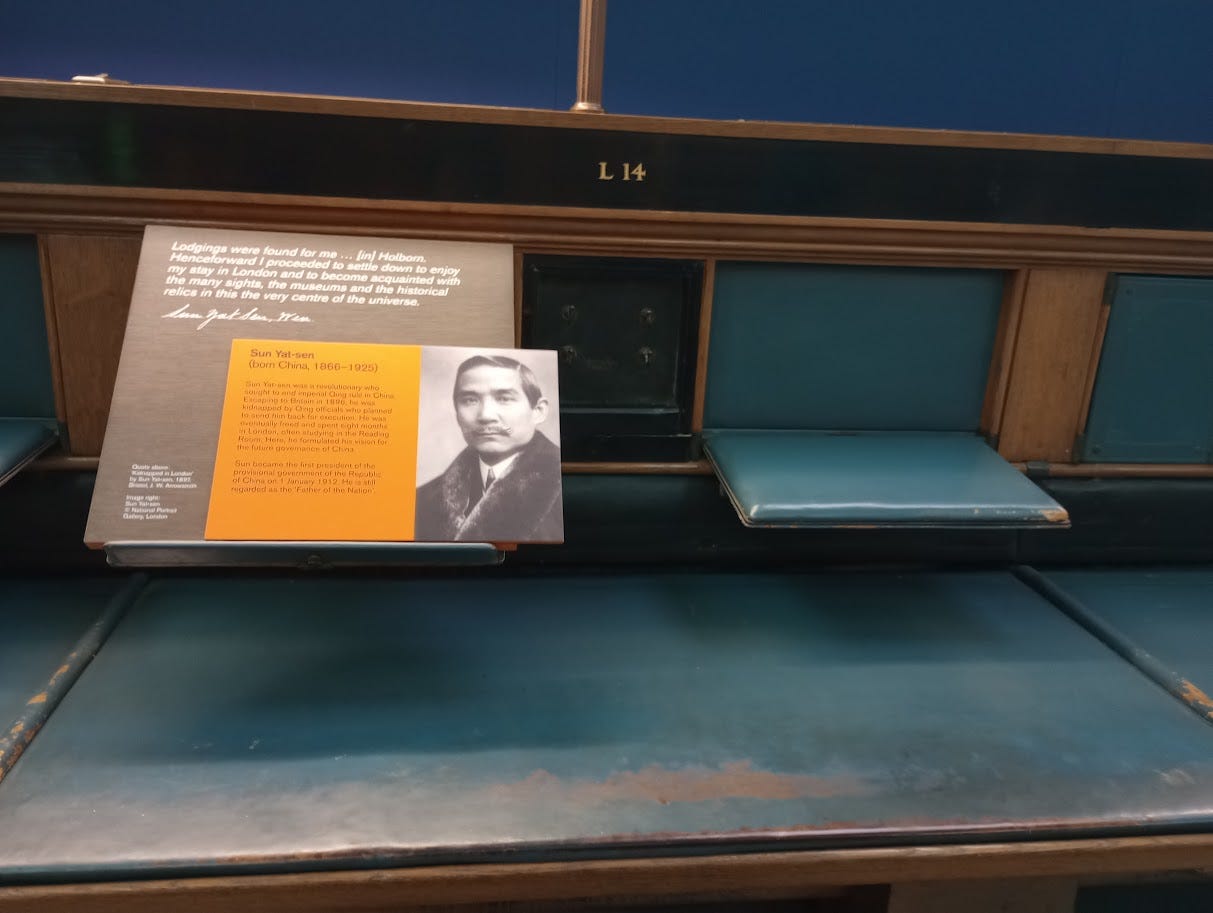

Another, very different, reader in the British Library: Chinese revolutionary and thinker Sun Yat-sen, who had no plans to take the Chinese people anywhere, but very much wanted its imperial rulers to go away:

Sun Yat-sen was not, as you might imagine, popular with China’s rulers , and like many Chinese radicals since, he fled to London, arriving in 1896. Goons from the Chinese government followed him, intending to kidnap him and bring him home to certain death. However, Sun survived the kidnapping attempt, and stayed. Here in the Round Reading Room, Sun developed his plans for a future free China. Both China and Taiwan claim him as a hero, but note that he was not a Communist, unlike . . .

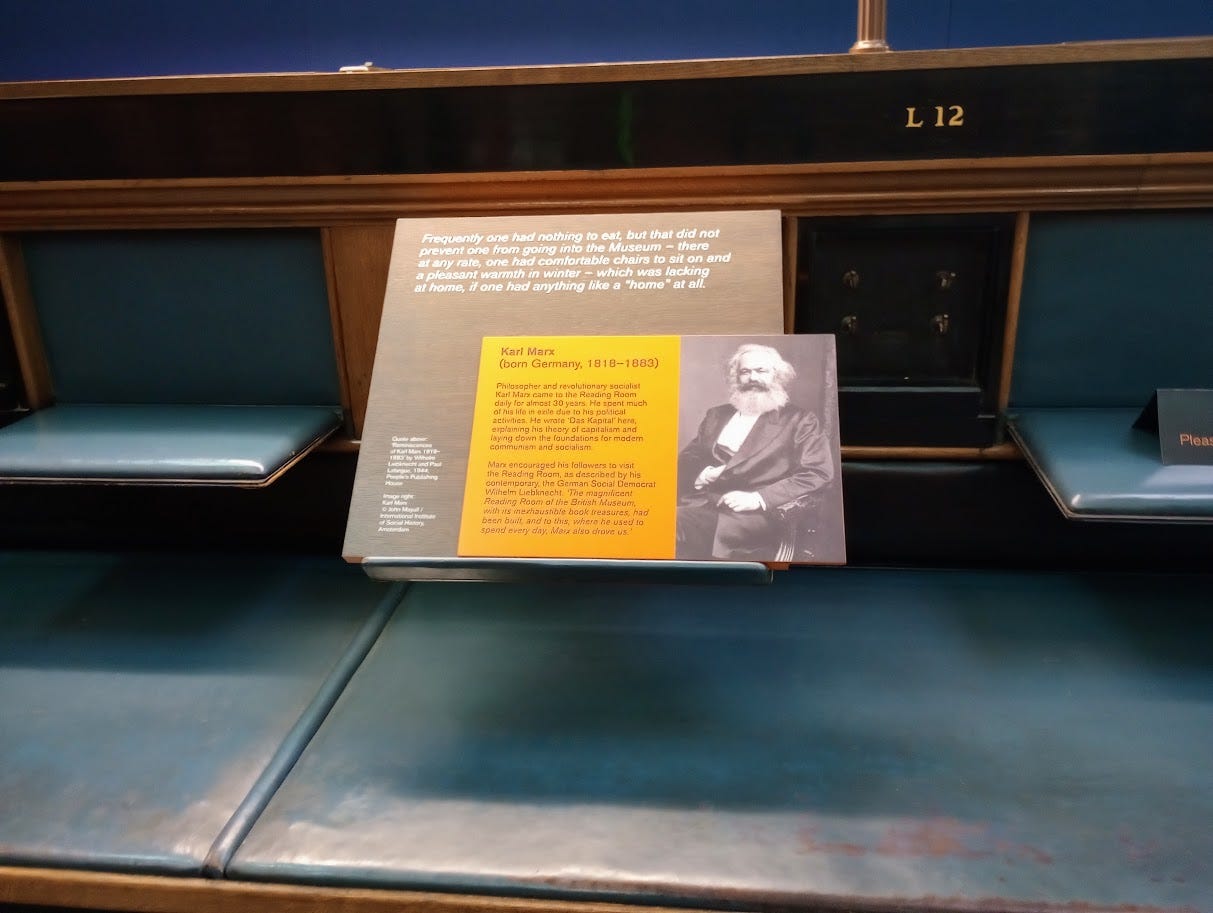

Karl Marx. The OG Communist. The Round Reading Room’s most famous occupant, he spent thirty years reading and scribbling in here. Poor and freezing, often hungry, in London, this exiled German political thinker was happy to hang out for hours in the Reading Room, which was warm and had (relatively) comfy chairs, before retreating across the street for a pint in the Museum Tavern.

Here in the Round Reading Room (and possibly in the pub, while thinking) Marx wrote Das Kapital (Capital), his most famous and influential book, in which he explained his theory of capitalism, and gave both communism and socialism (no, they’re not the same thing, despite what Shocky McJockFace says on the radio) a theory on which to hang their hats. And on which they might themselves one day be hanged.

Many Westerners have strong opinions on Marx, but very, very few have actually a clue who he was or what he wrote, beyond Marx=Bad, which is interesting when you think about it. I have read Das Kapital. I have also read Hitler’s Mein Kampf. I am neither a Nazi nor a Communist. Go figure.

Whatever our thoughts and feelings about Karl Marx, he had a huge impact that extended far, far, beyond the walls of the British Library. As history vanishes from schools and universities (and history in American public schools was never much a thing anyway) will anyone know who he, or any of these people, were? Not to be gloomy. Because I’m surprisingly optimistic about this sort of thing, or I wouldn’t be sitting here writing Non-Boring History.

Marx, by the way, would have despaired of me. Complaining about oligarchs one moment, and visiting Harrods the next? Insane.

Would be interesting to hold a big party in the Round Reading Room, and invite all the ghosts of readers past, wouldn’t it? Might end badly in a bit of a punch up, though. This was indeed a ministry of many truths.

(P.S. There were women who studied in the Round Reading Room, including the scary Virginia Woolf, but I’ve run out of time, so please note: Women are scholars too. But I bet you knew that.)

Moving On

In the late 20th century, it occurred to someone that the British Library’s reading facilities were again too tight for readers, and that it was time for British Museum and he British Library to make a full divorce.

Scholars protested (to no avail), especially when they learned they would have to decamp to a characterless modern building in the deeply depressing and seedy neighborhood around Kings Cross Railway Station (not even Harry Potter associations existed to console them, not yet). The Round Reading Room, sadly, closed in 1997.

But the new British Library, while ugly on the outside, proved to be a researchers’ paradise on the inside, and scholars quickly cancelled their complaints. I know, because I was one of them. I never got a chance to sit in the Round Reading Room (sob) but I very much enjoyed my visits to the new British Library. The collections—documents as well as a books- are amazing. After years of searching archives, I finally found correspondence there from one of the eighteenth century Anglican ministers in America I studied, and a quote so useful, I practically broke into a dance: Having been forced out of South Carolina, Rev. Brian Hunt had ended up in the West Indies, where he wrote a letter in which he alluded to what had gone down with him on the mainland, and how others might avoid his fate. Doesn't sound like much, I grant you, but it proved perfect for my article.

Oh, and don’t discount comfort when it comes to research libraries. Beautiful surroundings are all very nice, but, having suffered through hours of research in unsuitable chairs at libraries and archives that prioritized good looks over researchers’ backs (looking at you, South Carolina Historical Society), I give top marks to those institutions that care about the spinal health of the scholars who haunt them.

Hot tip: You can research at the new British Library (yes, you!), since they will give you a reader’s ticket (pass) so long as you have research in mind to which their collections apply. And if not? You can visit anyway, to see anything from the Magna Carta to the scribbled scores of Lennon and McCartney, or, indeed, the library of King George III, which is brilliantly exhibited.

But what about the very cool but now abandoned Round Reading Room at the British Museum? What to do with it? Finally, years later, we have the answer: Make it the largest exhibit in the British Museum.

It’s an odd set-up, looking like they piled up all the furniture to keep us out. Nobody can get close to the books still on display, alas, so I have no idea which books are in my photos. But the info panels displayed in carrels in the public area show why this was an important place, introducing us to a very few of the astonishing cast of characters who once sat here with books at their elbows, earnestly scribbling notes.

I’m sorry I didn’t make it to the “new” British Library, one of several plans that fell through on this trip. I will say that I’m glad it still exists, in a country that has been busily closing public libraries in recent decades. Oh, was that a secret? Well, it’s not, and I’m telling you about it. What a disgrace: Many of the local libraries that survive cuts end up being run by well-meaning but clueless amateurs presiding over moldering collections. This is why America’s library champions are so important, and you can and should be one of them: Write an email or even letter to politicians at every level if your public library is threatened with cuts: You may or may not use the library, but we all depend on it as an essential supplement to public education, for a society that needs knowledge.

Why do actual physical books matter? The Internet offers “book burning” opportunities unthought of by George Orwell or by Ray Bradbury, with information regularly vanishing off the web. Physical books still matter as much as ever, as does a library containing the vast and changing ideas of human beings, and human beings who care about such things, none yet replaced by the pathetic and dangerous joke that is “artificial intelligence.”

Non-Boring History is the one-woman show of Dr. Annette Laing, renegade historian in America, supported by her long-suffering spous,e Hoosen, and a crack team of Gnomes. In seriousness, what you just read depends absolutely on the support of Nonnies, paying readers. Become a Nonnie today. You won’t be funding a 7 million dollar condo in Manhattan—and that’s a solemn promise. You’ll be funding work you enjoy and find stimulating. What an old-fashioned concept.