Presidents Meet Destiny at the Buffalo Fair

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD A fun museum about the grim time when Teddy Roosevelt became president

Notes from Annette

Teddy Roosevelt didn’t become President in the normal way, but because of the assassination of President William McKinley. Today, I’m encoring a Non-Boring History post of mine about a very creative museum housed in the very building where he stepped into the role.

Wagons Painted!

Big thanks to the Nonnies (paying subscribers) who joined me for part 3 of Paint Your Wagon, my online talk series retracing the journeys of Gold Rush migrants in 1849, and me and Hoosen in 2018/19. Always such fun to see you all! Free readers, my online talks are a fun perk (if I say so myself) of being a Nonnie. Join us!

The Mr. Toad’s Wild Rides of History: Thoughts Going Into the Museum

Ever feel like you’ve been living through Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride at Disneyland? You're having a pleasant tour, only to take a sudden lurch into a nightmare that gets worse and worse, until the ride ends in Hell. Not the sort of corporate rides Disney makes now, but, hey! In case you’re not familiar, here's a video, cued to start with cheery music as we ride through the library at Toad Hall:

See, I have bad news! Things have always gone like this in history! But I have good news! We’re not alone.

And we never know when another sharp turn will happen. So maybe we'll have a better one that’s quite unexpected, just like in the video, where traumatized riders stepping off Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride are happily distracted by the sparkly carousel.

Today, I’m repeating a great story which originally ran here at NBH on November 27, 2021. It's about a small museum in Buffalo, NY, that freezes in time one fateful time in American history when things took an unanticipated turn, and pops that episode into enlightening context via entertaining exhibits.

My original post spotlit a second small museum, a British one on —get this—King Henry VIII. Nonnies (paid subscribers) will find a convenient link to the paywalled original in the Nonnies’ Bonus section at the end of the main post.

Bitten by the NBH bug? Be a Nonnie for just $6 a month (or less with an annual membership), and get access to everything. EVERYTHING, I tell you! And you’ll also make me and the Subscriptions Gnome and the Accounting Gnome at Non-Boring House very happy. :) Hey, we are working hard here for your entertainment and edification! :)

Death of A President

The Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site in Buffalo, New York was once a private home, belonging to a friend of, well, Theodore Roosevelt. It was here that Roosevelt, the youngest president in US history until John F. Kennedy, was hastily sworn in as president in September, 1901, following the death of William McKinley from an assassin's bullet. And that’s the reason for the museum.

The Big Story: The museum also takes us to a time when the United States economy was booming on paper and for a lucky few, but many Americans were living in misery.

The death of President William McKinley in 1901, like the death of Queen Victoria that very same year, conveniently marked a new century, and the official arrival of a new Progressive age, a time of efforts to address the downside of unlimited capitalism.

Hold on a minute. That was a bit convenient of both Queen Victoria and President McKinley to pop off at the turn of the century, wasn’t it?

No, don’t worry, I’m not proposing a conspiracy theory. I’m just suggesting that we beware of easy, tidy narratives. History is never easy or tidy. It is, to use the historians’ unofficial motto, complicated. Messy, even.

I warn you now, I'm not even remotely an expert on the Progressive Era in the US, and, in fact, it's pretty embarrassing to realize how little I know. My PhD is in early American history to 1820 and modern Britain. I’ve made up a lot of ground in 19th and 20th century US, but there are big holes in my knowledge, and this is one of them.

I am pretty sure, though, that it really wasn’t that tidy. Just one example: Progressive movements to improve the lives of the poor, like the Settlement movement I mentioned recently in my post on The House of the Seven Gables, had already emerged on both sides of the Atlantic.

President William McKinley supported union organizing, and was the first US president to visit Black leader Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute, a significant symbolic gesture in an age of massive racist violence against Black people. In other words, wasn’t he the first Progressive president?

But McKinley died. That means we’ll never know what he would have done during his remaining time in office. Teddy Roosevelt gets the credit for things McKinley might have done.

I'll write about all this properly in Tales someday. For now, let's just say that this Museum got me interested in Teddy Roosevelt and William McKinley. And that's pretty high praise. Let’s see if I can get you interested, too.

All the Fun of the Fair!

We start in an exhibit that's right off the basement level reception. Its theme? We, the museum visitors, are at a fair.

Fairs are one of my obsessions. I wrote recently about Coney Island at the turn of the last century. But I didn't expect to write about amusement parks again quite so soon, and especially not at a museum about a Presidential inauguration that was triggered by the assassination of the previous President.

It surely seems in incredibly bad taste to apply a carnival (UK: fun fair) theme to the first exhibit.

The fact is, though, that the inauguration that's the reason for the museum happened because President William McKinley was assassinated at a fair: The Pan-American Exposition (Exhibition) of 1901, held in Buffalo, New York.

Oh, that grandiose name for an event doesn’t sound like it was really a fair, does it? Aren’t I reaching a bit here?

No, I’m not. Stick with me.

The Pan-American Exposition (Exhibition) of 1901 was a direct descendant of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the original World's Fair, held in London a half century earlier to celebrate industrial progress.

As I wrote in The Crystal Palace and the House on the Rock, the Great Exhibition was not, for its visitors, worthy and informative so much as it was an amazing spectacle. And it set the tone for World’s Fairs ever after: Yes, sure, they were platforms for nations boasting about their industrial prowess, but they weren’t just patriotic trade shows. They were crowd-pleasers, showcasing the exciting, the peculiar, and the downright fun.

And there were a lot of crowds to reach in 1901. The United States was also now an industrial country, fast catching up with Britain. Much of its factory labor was provided by immigrants, crammed into the slums of rapidly-growing cities. That meant that forty million people now lived within a day’s train journey of Buffalo and the Exposition.

Oh, sure, the official goals of the Pan-American Exposition were a bit loftier than a fun day out for all. Its official purposes were encouraging trade between the US and its Latin American neighbors, and educational uplift for the masses.

As President McKinley put it, in a speech at the fair the day before he was shot:

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress. They record the world's advancement. They stimulate the energy, enterprise, and intellect of the people; and quicken human genius. They go into the home. They broaden and brighten the daily life of the people. They open mighty storehouses of information to the student.

Uh-huh. But let’s get real, shall we?

As we at Non-Boring House can attest, you don’t attract millions with the promise of uplifting education and intellectual stimulation. You reel them in with glitz, glamor, and exciting entertainment. Or, if you're the staff at Non-Boring House, you just do your best, because your damn integrity keeps getting in the way, okay?

The Exposition in Buffalo offered expensive and beautiful purpose-built exhibit halls, just like the newly-revived Olympics, a product of the same era, and no, that’s not a coincidence. So the Exposition was a glamorous and exciting place for a day trip. Making full use of the electricity from nearby Niagara Falls, it was also a wonderland at night.

The Exposition looked, in fact, not unlike New York's Coney Island, also not a coincidence, since Worlds Fairs and amusement parks were the products of the same era, and each influenced the other in architecture, technology, and glitz. Indeed, at least one exhibit from the Buffalo Exposition, “Trip to the Moon”, ended up at Coney Island.

In case you’re curious (and because this was a thing by 1901, ooh, this early Americanist sometimes gets jealous of 20th century historians) here’s a one-minute film by Thomas Edison’s movie company, showing the Pan-American Exposition by day, and by night.

Appealing to ordinary people looking for joy in the midst of a unprecedented economic depression, the Exposition was literally a bright spot in a troubled time.

It’s All About Timing

The Pan-American Exposition arrived at a perfect moment. In 1901, the people of the United States were emerging from their first traumatic experience of industrial depression.

I see your eyes glaze over, and I can only apologize for that. It's also not helpful that this multi-year depression, a catastrophe for many, many ordinary Americans who went into freefall, became misleadingly known as the "“Panic of 1893,” which tells us nothing. How much of an impact could something have that sounds like it was over in minutes, and only merits a line or two in a typical awful textbook?

The Panic of 1893 was, in fact, a full-blown Depression, lasting for four entire years, from 1893 to 1897. Its impact? Massive. This was the Great Depression before the Great Depression. Just one indication: Unemployment in New York reached 35%. 43% of people in Michigan were unemployed. 50% of industrial workers in Ohio were jobless. In real people terms: People starved. Families broke up. Women turned to prostitution to feed their kids. Desperate folk killed themselves. These impersonal facts only hint at the vast suffering.

And the only help for the struggling? Spotty assistance, from overwhelmed local government and private charities.

No federal unemployment benefits. No national system of welfare. And the powerful and appealing narrative of limitless opportunity in industrial America ensured that it wasn’t enough that poor people suffered: They were to be made completely miserable, blamed for their own fates.

The voters, though, somehow knew there was more to it than that, even if they didn’t quite know what. The Depression was blamed on President Grover Cleveland. He lost in the Democratic primary to William Jennings Bryan, who in turn lost the Democrats the White House in the Presidential election of 1896.

The winner? Republican William McKinley, whose Vice President was Theodore Roosevelt. If the terms “Democrat” and" “Republican” as we know them don’t quite seem to fit here, that’s because ideas, and with them words, change.

But that’s enough political history for now. I’m here at the museum as a visitor, and just like the people who went to the Pan-American Exposition, I am mostly hoping to be entertained.

Show, Don’t Tell

So the museum begins by evoking the festive setting of the Pan-American Exposition. Starting with the fun of the fair helps brings home the grim everyday reality of millions of Americans’ lives in 1901, and the horror, tragedy, and gravity of what happened in September of that year.

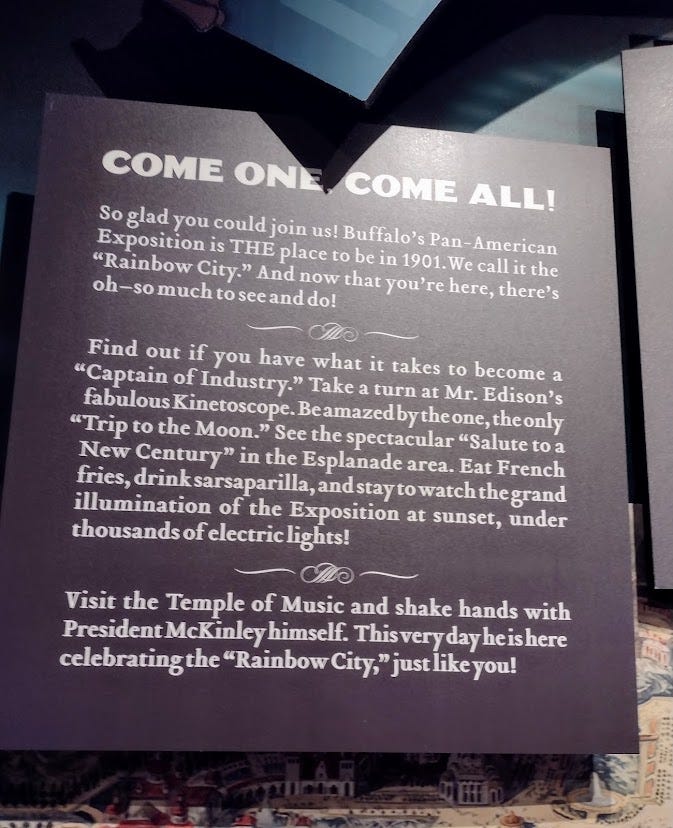

Let me not just tell you about the museum, though, but show you, starting with this info panel.

Notice how the Exposition’s serious goals are not mentioned in this simulated invitation to the public, written by the museum to get you into the spirit of the day. That’s because, to repeat, millions of people didn’t come to Buffalo in 1901 to learn about international trade. They came to have fun. They came to bring home pretty souvenirs, like this plate. Artifacts like this bring home to us today: This was real. This happened.

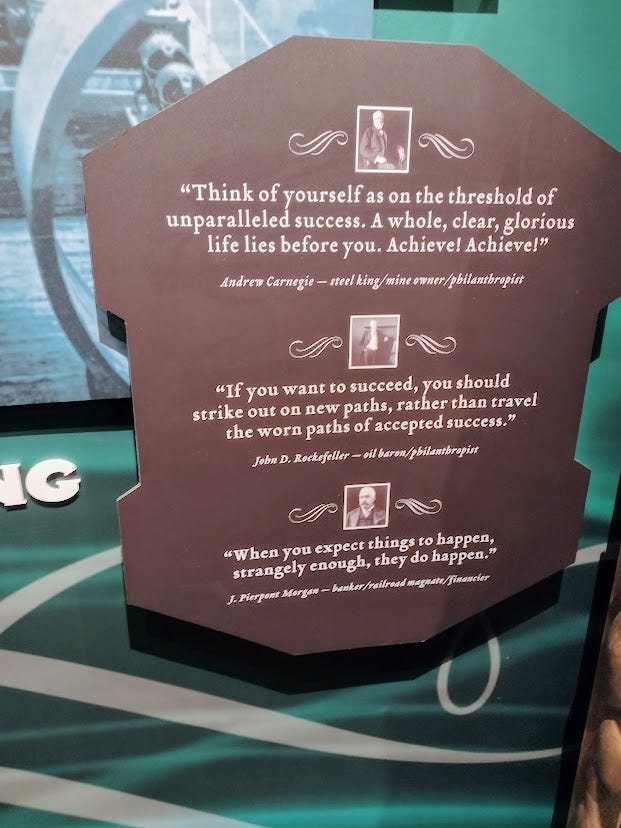

And now, here’s some advice from 1901 America’s Captains of Industry, the Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk of their day, on how to be as successful as they are.

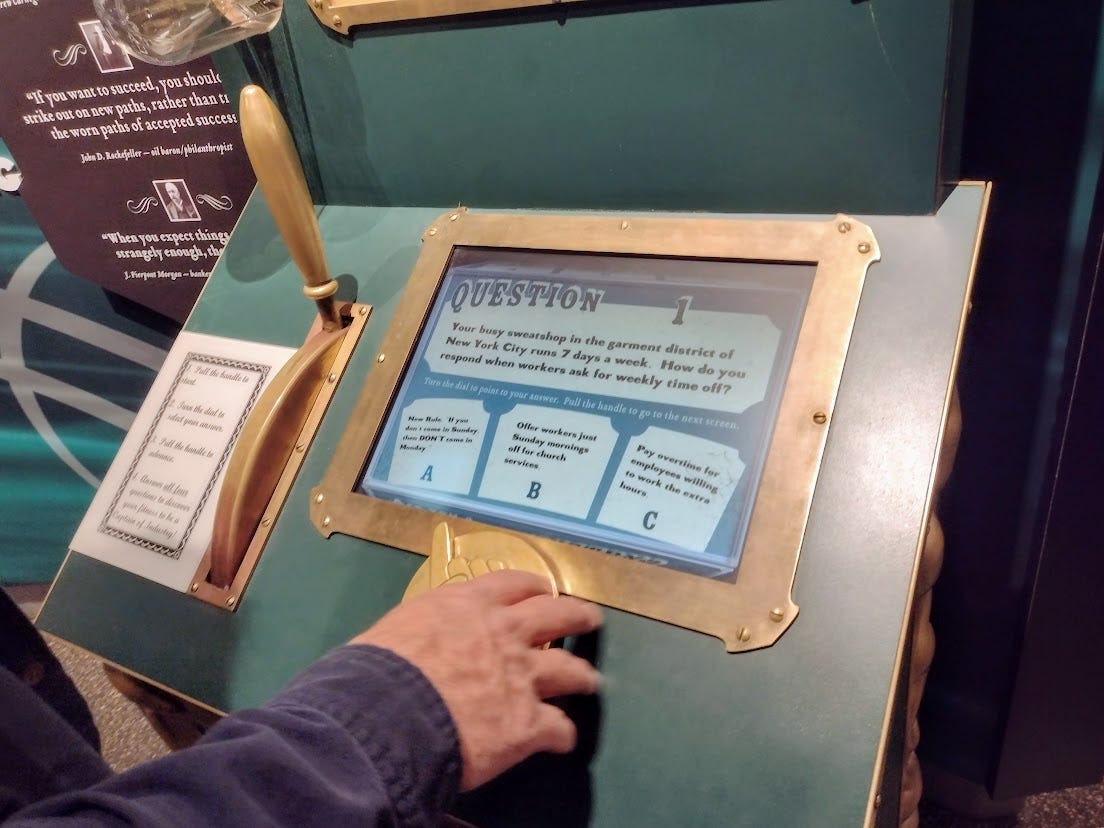

Right next to their advice, an exhibit that’s much more likely than the info panel to have drawn your attention. Ooh, I love this sort of thing! It's one of those fairground machines that claims to measure your macho-ness!

Except it's not. You don’t get a high score on this machine by squeezing the handle. Instead, you get it by answering several multiple choice questions about the lives of industrial workers in 1901. You hope you will get the answers right and impress your companions with a high score. But the museum doesn’t care if you get it right: These aren’t questions for questions’ sake, but to deliberately introduce a note of doubt into the celebratory story it otherwise seems to be telling.

Here’s Hoosen having a go.

Turns out, none of these questions, about the lives of ordinary Americans in factories and mines, has a happy ending. The most depressing answer is usually the correct one, and even the “best” answer doesn’t suggest much joy for industrial workers. This simply wasn’t a happy time for a lot of working people, and they tended to blame themselves for that fact, which helps explain why so many were so frantically enthusiastic about celebrities, men like Carnegie, Morgan, and Rockefeller. Look, these guys are successful! They’re even nice enough to tell us why (see above!) They say nothing about ruthlessness, good luck, or lack of integrity, or even hard work, just smiley optimism! Indeedy!

The 1901 Exposition is not without its cringe moments for us in the 21st century. You could visit an “African village” where, the Fair’s program advised, you could see representatives from 25 different African “tribes”, with their “supremely ancient weapons, household gods, and primitive handicraft”, or the Streets of Mexico, where musicians (mariachis, I’m guessing) played “their peculiar native instruments.” I’m certain the words “primitive” and “native” appeared a lot in the Fair’s advertising, but before we get too smug about how enlightened we are today, this doesn’t seem quite so far removed from Disney’s World Showcase in Epcot, and that’s not a coincidence, since Epcot’s roots lie in World’s Fairs. All the stereotypes, none of the actual travel. People in 1901 had a good excuse why they couldn’t travel the globe and actually meet people. Many of us today have, until very recently, had less of an excuse.

One Terrible Moment

In an instant, joy and excitement at the Fair turn to horror, when the optimistic and joyful came face to face with that other, miserable America.

Excited fairgoers have lined up at a public meet and greet with President McKinley, a chance to shake hands with not only a celebrity, but the President himself. It’s a hot day, and most hold handkerchiefs in the standard white to wipe their faces.

An unemployed steelworker who was laid off the year the Panic began, in 1893, the son of Polish immigrants, arrives at the front of the line, and stands before the President of the United States. Leon Czolgosz, age 28, holds out a hand covered in a white handkerchief. A hand that's holding a gun.

He shoots twice, one bullet piercing McKinley's abdomen.

Standing behind Czolgosz is James Parker, from Georgia. James Parker had just been laid off as a waiter at the Exposition, and had decided to explore the fair before starting the wearying search for a new job.

Now, Parker didn't hesitate. He grabbed the gun before Czolgosz could shoot again, and punched him to the ground.

At a time when the white South (and much of the rest of America) was waging war on Black Americans, torturing men and women to death as a warning to them to stay in their place (“lynching” doesn’t quite capture how bad things were), the hero of this moment was a Black man.

James Parker, who could have been murdered for punching a white man in Georgia in 1901, no matter how justified, was the first person to come to the rescue of the United States president.

From here, the speed of the museum suddenly picks up, while in real life, there was an agonizing lull. President McKinley was expected to survive. Vice-President Roosevelt, who had interrupted his vacation to visit the wounded President in Buffalo, returned to Vermont.

And then, on September 14, McKinley died from his wounds.

A New President

The tour guide—for there is one-- leads us upstairs. It’s a big building, but the museum only occupies a few rooms. Now we're in the restored front hall of the house, wiped clean of evidence of later inhabitants, and we pop into the dining room, restored to its turn-of-the-century splendor, to imagine Theodore Roosevelt paying his respects to Mrs. McKinley before his inauguration.

Freeze there. We now step back across the hall for a multi-media presentation about the United States in 1901: Terrible working and living conditions in the cities among a mostly immigrant workforce. Horrifying child labor in factories and coal mines. The violence of whites against people of color, and especially Black people. Environmental destruction on a breathtaking scale.

This is what Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt was about to confront.

And then we walk back across the hall into the study where Roosevelt was inaugurated, and see the exact spot (marked by a coffee table) where he’s believed to have stood to take the oath, and where it was made official that he was president. Writing in 2024, three years after the original post, I can’t help smiling to myself that, as ever, Teddy Roosevelt steals the show: This is not a museum where the focus is McKinley’s life, or his shocking assassination, or America in 1901, but Teddy Roosevelt’s moment of glory.

As it happens, Roosevelt didn't hang about: He hit the ground running. On the very day he was inaugurated, he wrote a letter to Booker T. Washington, announcing his intention to invite him for dinner at the White House. There was, both men knew, going to be a massive brouhaha: White Southerners had been outraged when President McKinley visited Professor Washington at Tuskegee Institute. For the President to eat with a Black man was absolutely unthinkable to white Southerners. That it was a Black man from Georgia who had bravely tried to save the life of the late president was not considered relevant.

Did President Teddy Roosevelt, son of Mittie Bulloch of Roswell, Georgia, descendant of slaveowners, know exactly what he was getting into when he wrote to Booker T. Washington? This is just one of many questions that the Museum anticipates, and invites us to learn for ourselves.

Oh, and a PS? The heavy and visible Secret Service presence that we are so accustomed to seeing around the President? That started now.

Questions? Comments? Comments at NBH are exclusively for Nonnies, subscribers to Non-Boring History. Why limit interactions to readers who pay? Simply put, I just don’t have time: This is more than full-time work. When my readers give back, I can keep doing this. Become a Nonnie today! Here are the details, and clicking the red button does NOT automatically charge you:

Nonnies’ Bonus

Read my original post (with an extra fun story about Henry VIII, delectable pie photos, and more!) and other news from NBH!