Historians Construct, Destruct, and Reconstruct

ANNETTE TELLS TALES Early 20th century cuckoos who misled generations of Americans, and the historians who fought back

Note from Annette

Here's my most recent post for subscribers:

Today, the Quality Control Gnome at Non-Boring House reminded me that readers are exhausted by current events. The NBH Compliance Gnome , meanwhile, is terrified I'll offend someone important, or anyone, really. Both of them demanded I send you a fluffy post today, perhaps an AI picture of George Washington holding a kitten that matches his wig.

Nah, I said. Let's talk about a massive case of historical malpractice and the historians who fought it.

That Can't Be Right, Can It?

As a British teen, newly arrived in California, I was absolutely baffled by how I was taught about Reconstruction in my US history classes.

What’s Reconstruction, my non-US readers may ask? My US readers, meanwhile, should not be sure they know what it is, because that’s our big story.

For now, here’s how I understand Reconstruction today, in short:

Reconstruction is the name we give to a brief time after the Civil War. As the South lay in ruins, agents of the federal government, Black communities, and progressive whites were working to integrate the recently-defeated South into cutting-edge 19th century America.

Reconstruction ended slavery, recognized former slaves as citizens, and began bringing new industry, infrastructure, and public education to the South, including to poor whites. Much of this progress was funded by the federal government, including, just one example, the transformation of the University of Georgia from a tiny crappy school into a public institution that was starting to look like a real college.

The former Southern elite, however, was resentful and determined to maintain whatever they could of the old system under slavery.

Led by former Civil War officers, the Southern elite did not take their loss of power lightly. They literally fought Reconstruction all the way, with violence and terrorism. In the end, Northern white apathy did the rest, and Reconstruction was abruptly ended by the federal government in 1877. A bright new day for the South was strangled at birth.

The South was handed back to elite white Southerners. What followed was “Jim Crow”, a brutal system of racial segregation enforced with violence and terror, a system that only truly benefited a few people at the top, while the rural South relapsed into poverty, inequality, and misery. Poor whites were flattered by the white elite, who told them that, while they might still be poor, they should think of themselves as superior to black people, whose rightful place, they were told, remained at the bottom of Southern society, below even poor whites in a system that turned many of them as well as former slaves into sharecroppers, peasants trapped in debt.

The only thing left to utterly crush Reconstruction was to present it as having been a corrupt failure. But how could this be done when that was not true? Couldn’t historians in American universities have corrected this lie with evidence?

Good grief, where do I even start?

If you're a long time reader of Non-Boring History, you may remember I already wrote about how elite white Southerners, led by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, launched a massive and wildly successful propaganda campaign after Reconstruction to present slavery as a positive good, the period before the Civil War as a happy time with contented slaves, modern black Southerners as hapless children, and Reconstruction as a disaster.

Most historians didn't fight this around the turn of the last century, and those who did, all of them black, were ignored by the others, until things began changing in the 1930s, and especially after WWII. This sounds like a cut and dried story of the ol’ racism, doesn't it? Much of it is, make no mistake, but it’s actually even more interesting and complicated than it sounds. Historians don't set out to make stories simpler, but to complicate them. That's why this is not my first dip into this subject, and it won't be my last. It’s worth digging deeper, including to start introducing you to historians who worked to correct the lies, then and later. Don't assume there's anything obvious about this story: It's amazing. And I hope it gets you thinking about how we all know what we think we know.

Most importantly, I want to get across why this story of corrupted history matters to everyone living in an age in which so many people struggle to know what to think and believe.

Fasten your seatbelt!

Encountering American History

Newly arrived from England in the early 1980s, still pronouncing garage as “garridge”, spelling color with a “u” and referring to erasers as “rubbers”, teenage Annette (future Dr. Annette Laing, historian) enrolled in high school in California.

In US history classes, both in high school and later in university, I was taught that Reconstruction was a disaster, dominated by men with weird nicknames: “carpetbaggers” were mustache-twirling villains from the North who came South to make a quick buck. “Scalawags”, I was told, were native white Southern grifters, who exploited former slaves and colluded with carpetbaggers. And formerly enslaved people? They were shadowy figures, pathetically innocent, ignorant, and hapless, according to this narrative. Former slaves just waited for stuff to be done to them, I was told. Some were elected to office, I was told, but they were predictably corrupt and incompetent.

Tell that to the black farmers in the later 19th century who donated land for schools all around the South. Tell that to the community leaders, ministers among them, who lobbied for education and economic opportunity. Tell that to the idealistic evangelical Christians, black and white, who hurried from the North to teach eager freedpeople everything from basic literacy to college-level work. Tell that to Blanche Bruce, former slave educated at Oberlin College, who served in the US Senate. Tell it to the generations of historians, black and later white, who have fought this rubbish tooth and nail with real evidence. I don’t like all trained historians (those with PhDs in history). But I do trust them to be honest, because the exceptions to that rule today are few. We disagree, but we fight with facts. Our battles now are with people who don’t share our commitment to evidence, and —tragically—some are regarded as great historians by a public that simply doesn’t know.

I couldn’t have told you anything worth hearing about Reconstruction in the early 1980s, or long afterward (even when I took a PhD, it was in early American history, which doesn't include the 19th century.) See, I just didn’t know. Neither did my American classmates, or my Californian teachers. Why?

A Survey of Ignorance

My California history teachers weren’t making stuff up about Reconstruction. They were teaching what they genuinely believed to be the truth. It was rubbish anyway.

One problem? Like everyone in America, I first took US history in so-called survey classes.. These attempt to cover the entire sweep of US history from pre-Columbus to Trump in one year (and -get this— I had to teach a survey in one half year at the “university” where I formerly taught. That was nuts.).

The US history survey is a rapid yet tedious and bewildering trot through dates, names, and unfamiliar events. This course is taught again and again to American kids. They take a survey in elementary school. They do it again in middle school. They do it again in high school. And if they attend college (aka university), they get it a fourth time, often taught by graduate students, moonlighting high school teachers, or others who drew the short straw.

Surveys are typically the only history classes required by US state laws. These are the only history classes the vast majority of Americans will ever take. And, dear God, they are bloody awful. Most of them are boring and all of them are painfully superficial. These classes are essentially unteachable, and most of those charged with teaching them are deeply unprepared.

Like me, back in the day! Hey, I have little formal education in 19th century US history, since my PhD is in early America, modern Britain, and 20th century US. I taught my very first US survey class at Cal State University, San Bernardino in 1991, as a newly-minted MA. At our first meeting, I had a desperately awkward moment. A student brought up someone called “Henry Clay, the Great Compromiser”. I tried not to show my panic. Who the hell was Henry Clay? A Victorian magician? I bluffed and got the student to tell me. Phew. After barely surviving the semester, I decided to wait another couple of years before teaching another class. And that’s exactly what I did.

If you think that was bad, you should have seen me later, when I had to try to teach the survey class in ancient and medieval world history, after a department chair desperate for a warm body to cover the class talked me into it. If I had had to take my own tests, I would have failed them. I never made that mistake again.

The Textbooks of Death

So if you're teaching stuff you don't know well or at all in the survey, and you haven't time to teach any of it well anyway. how do you teach it? You teach it badly, that’s how. Best you can hope for is to be entertaining, and get kids interested in real history.

For my first few years in charge of college survey classes as a young PhD candidate and later professor, I made a lot of jokes, and, like everyone else, I relied on students reading a gruesome and massive corporate textbook. Not that I read it myself: It truly was what history is often accused of being, one damn thing after another. Surveys and I have never been friends. In the end, I got a grant to do a different kind of survey class, and it was, I must boast, much better.

But that’s not today’s subject. Back in the early 80s, when I was a bored and disappointed British teen suffering through required US history survey classes in California, I couldn’t help thinking that the portrayal of Reconstruction, especially, was not just boring, but deeply weird. How did I know that, though? I never had taken a US history class before. I didn’t recall ever reading about Reconstruction.

Well, I’ve finally figured it out.

The Roots of Annette’s Suspicions

And now it hits me: As a kid in England, as I have often mentioned, I first encountered American history by watching Roots, the epic 1977 historical drama about a black family in slavery. Now I think about 1979, while I was still living in the UK, when I watched the sequel series, Roots: The Next Generations. While my memory of the program has faded, I'm guessing Roots 2 did a much better job of teaching me about Reconstruction than did my survey classes in America.

There's more: Inspired by Roots, I found a book on black American history in a used bookshop in London. From Slavery to Freedom was written by an American historian named John Hope Franklin.

I remember struggling with Dr. Franklin’s book. Although it focused on black history, it was a broad textbook of the kind I had yet to meet and loathe in the States. At 14, I was precocious, and already had started to read academic British history books, which explained their subjects in detail. I had never read US history, or even been to America. In John Hope Franklin’s book, I didn’t understand much of what I read. But I was very interested in what I could understand.

Now I realize that what I learned from Dr. Franklin’s book was also very different from what I would be taught later in American history survey classes.

By the time I got to California, I had forgotten the particulars of From Slavery to Freedom. But it had made an impression that left me prepared to be skeptical about what I was being told by high school teachers about Reconstruction. I also realized immediately that my first American teachers were appallingly ignorant of any US history.

Coach Grunt, as I shall call him since he's not dead yet and might sue, was a miserable git who handed out worksheets and told us to read the textbook to prepare for our weekly multiple-choice “quizzes” on the tedious facts in the textbook. He then put his feet on the desk. I think he was stoned.

I very rapidly educated myself in US high school bureaucracy, and within 24 hours, had extracted myself from Coach Grunt's clutches, and fled to another class.

My second US history teacher was Mr. Kind But Useless (also still breathing, amazingly). I quickly realized that he, too, knew less about American history than I did: Unlike Coach Grunt, however, Mr. KBU gamely tried to lecture to us. Having nothing relevant to say, however, he was quickly reduced to reading to us from the textbook.

This was not Mr. KBU’s fault, or Coach Grunt’s. Part of the problem, I would learn as recently as last year, was that US history survey courses originated as a vehicle for patriotism, not serious history. And who needs history? It’s all names and dates, right? Elementary school teachers often have almost no background in it. In high school, history is often handed off to coaches and struggling teachers like Mr. KBU. Meanwhile, the battle cry of Colleges of Education, which train teachers in valuable skills like making posters with colored pens and glitter (don't get me started) is this: “Good teachers can teach anything!”

No, they bloody can't. Don't be stupid.

The Great Misleading

Where did the weird interpretation of Reconstruction come from? In schools, it had deep roots, planted by some of the most skilled propaganda-peddlers ever, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, or UDC. Yes, I know I've written about them before, but please bear with me

Distinguished historian Dr. David Blight has half-joked that the UDC could have taught a thing or two to Josef Goebbels, Hitler’s head of propaganda. The Daughters were founded as a national society of pro-Confederate white Southern women. They promoted a made-up history for schools—complete with books, articles, and lesson plans—that deliberately misrepresented their racist and fact-free opinions as history, known (very confusingly) as the Lost Cause. Yes, it influenced Gone With the Wind (book and 1939 movie).

Thing is, once you learn something like this in your youth, it’s hard to get it out of your head.

Look, many years ago, I attended a talk to historians by Dr. Joyce Appleby at UCLA. She was a very no-nonsense historian of US political thought in the early American Republic. Halfway through her lecture, she wearily took off her glasses to complain—quite rightly—that when people hear historians say something that differs from what they heard from their 4th grade teacher, they assume we’re lying to them. We all laughed and nodded: We had all run into this in talking to students and, especially, the public. We weren’t making things up, but someone had, and had taught it to teachers, who taught it to impressionable kids. Alas, time not being infinite, and her talk being on something else. Dr. Appleby did not pursue her point. But why didn't we know how this had happened?

Today, the nonpartisan historical profession (aka the profession to which professors teaching about the past typically belong—and all should belong), is one in which scholars, no matter our personal biases, work together to put evidence and the pursuit of truth first. And it is in a fight for its life.

Academic historians believe that everything changes over time, that everything has a history. We know (but find it hard to admit) that academic history is not an exception to that rule. The past does not change, of course, but history does change, because history is the interpretation of the past. Academic history as we know it, based on documents and historians engaging each other’s work, is only about 120 years old. Like everything, it had a beginning, which means (disturbingly) it will also have an end. And the end seems near.

Let's return to how the story of the misrepresentation of Reconstruction started, and it wasn't just the fault of the Daughters of the Confederacy, those armchair amateurs in crinoline dresses. Oh, how people love to blame women.

Let's find out why some academic historians in the US actively colluded in the cover-up of Reconstruction, while others—not being specialists, trusting their professional fraternity, and —let’s not be coy—some, but not all, being seriously racist— didn't even realize it was fake. As historians do, they trusted what their fellow “expert” historians told them. Let's start to understand the immense damage that caused. Let's shine a quick spotlight too on just some of the historians who worked to undo that damage.

A Gentlemen's Agreement

In the late 19th century, US history was written by white gentlemen who were either rich amateurs, or professors with cushy offices and light teaching workloads in fancy universities like Harvard, who wrote readable but frothy history. Some of them were starting to worry their professional standards could be higher, especially after they saw the high quality of history emerging from Germany.

In the late 19th century, German historians were trying to make history a social science, rather than a branch of literature, as it was in America. The Germans were examining massive amounts of documents in dusty archives, and writing clinical reports, boring as hell, but supported by mountains of evidence, and beginning to form a body of knowledge.

Meanwhile, what we now call professional or academic history was just emerging in America by 1900. Like I said, in America, academic history had been written by gentlemanly professors. They were not specialists. Their PhDs were given for an interesting dissertation, not for mastering a specific discipline or body of knowledge. They pulled colorful stories out of their finely-attired arses, confidently presented these dubious tales in attractive grand-sounding language, and called it history. In doing so, they drew on their wide reading and vivid imaginations.

Actually, that's kind of like NBH, which is about history, but which I've always made clear is a creative mix of history, journalism, humor, and imagination. Hey, at least I have a proper PhD in history and try my best to keep things real. And my readers include Scary Historians breathing down my neck, whom I ask to let me know if I accidentally mislead you.

The First Proper Historians Are Improper

Woodrow Wilson, the first US president to hold a PhD, was a historian, but he was a transitional figure, as were most of his contemporaries. Wilson's PhD (1886) was in history and political science. His doctoral dissertation —a big piece of original work—was on political ideas, not history. This is hardly surprising since most American history as we know it today had yet to be written, so he didn't have much context in which to embed his work. In Wilson’s first university teaching jobs, he offered classes in ancient history, world history, and political science, among others . . . He even coached the football team.

By 1900, university history as we now know it—for better and for worse—the kind in which historians with PhDs are supposed to build on the work of other historians, using archival documents, was still not quite the standard thing.

But it was starting to become the standard thing, slowly. It did so slowly, because serious scholarship from scratch takes time: It took me ten years to have enough evidence to write my best article. Heck, it takes me several days, a week, or even a month to write NBH posts.

The new improved history was just emerging in the early 20th century. It was starting out only a couple of decades after Reconstruction was crushed. It was developing at the time of the greatest anti-black violence in American history—”Jim Crow” ruled the South, a system of racist segregation designed to humiliate as well as discriminate, and lynching, a form of terrorism intended to intimidate Americans of African descent from claiming their rights as Americans, , as white Southerners reasserted white supremacy.

And among these white Southerners were men training to be new professional historians, embracing respect for documents and truth . . . so long as it was “their” truth, and so long as the documents agreed with them. Anything that did not confirm their biases was to be ruthlessly suppressed.

The Cuckoos

Princeton University Professor (and later US President) Woodrow Wilson lived in New Jersey, in the North. But he was born and raised in the South. When Wilson was a child, his family owned slaves. Ever after, he defended slavery as a Good Thing.

Wilson was just a year older than Professor William Archibald Dunning, who taught at Columbia University, in the adjacent state of New York. Dunning, a Northerner from New Jersey, thought slavery was Wrong.

I don’t believe they knew each other, but these two historians had a lot in common. Despite their differences over slavery, they were both racists, like most white Americans of their time. They assumed people of African descent were inferior.

Dunning and Wilson both also believed that history needed to be a profession, based on original documents, and written by professionals, not fiction and wishful thinking written by wealthy gentlemen. At the time these two earned their PhDs, however, professional history was still in its infancy.

Dunning was one of those professors leading the way into the brave new world of history. He did this even though history wasn’t actually his first love. He preferred writing political science. However, he had spent a year as a graduate student in Germany, where professional history was much further along the road to being a fully-fledged discipline, with its own rules and methods.

Dunning once dabbled seriously in US history. He wrote a book about Reconstruction, and he concluded—based largely on the opinions of white Southerners he met and his own racist prejudices— that white Southerners had been done wrong by “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags”.

Dunning’s book on Reconstruction, weak though it was, got the attention of young, wealthy white Southerners, who clamored to study with him. He accepted a lot of PhD students. Dunning, of course, was thrilled to have eager young fans, even if they were drawn to him for a book he'd regarded as a detour from his serious work on political theory. He gladly mentored his young Southern proteges, who repaid him with adoring flattery. This praise no doubt quelled worries in Dunning’s mind that his book on Reconstruction had been amateur tripe.

Soon, Dunning's spawn students, armed with Columbia University PhDs granted for dissertations based on cherrypicked documents, bigotry, and wishful thinking, were embedded like ticks in universities in both South and North. They taught what we now call Lost Cause mythology, pushing white supremacy, and condemning and mocking Reconstruction. These new professors were not only teaching students, but active in the emerging national historical profession, including in the American Historical Association (AHA)

Black historians—and white women—were never banned from membership in the American Historical Association (AHA). But they were not made welcome, either. Even German -trained Harvard PhD and posh New Englander W.E.B. Du Bois learned this the hard way when he dared attend the 1909 AHA meeting while being a black man.

Du Bois presented his paper, Reconstruction and Its Benefits under the steely gaze of William Dunning and his many proteges. He was no weenie, Du Bois. He was famous in Europe for his intellectual prowess. But after this dismal experience, he never came back to the AHA conference, and other black historians followed his lead.

By 1913, the president of the AHA was (yup) William Dunning. Under his leadership, the AHA’s annual conference was, for the first time, held in a Southern city: Charleston, South Carolina, deep in the former Confederacy.

In short, William Archibald Dunning and his white Southern PhD students kidnapped Reconstruction history, Southern history, and Black history at birth. They established themselves as the “experts” in the new historical profession, paying lip service to archival research while making stuff up.

Among other lies, they claimed that Reconstruction had been harmful to the South despite massive evidence to the contrary. They set the tone for how Reconstruction would be taught in America’s most prestigious universities, not seriously challenged among white historians until after WWII.

Black historians, meanwhile, formed their own professional associations and scholarly journals. They researched and wrote actual professional history. They were ignored by white historians and the white public. Black historian Carter G. Woodson, another Harvard PhD, launched Negro History Week (the ancestor of Black History Month) but that was only held in segregated black schools. You may still be wondering: Why was Negro History Week needed at all?

I can answer that: Dunning and his followers got their claws into America's schools, all across the nation via the Daughters of the Confederacy. And the rubbish they peddled was still being taught in the 80s, and sometimes in more recent years.

That's why many Americans still believe the Dunning version today, while dismissing the work of black historians going back to Du Bois, and white historians since at least World War II, whose work is based on, you know, actual evidence. That's why the public regards anything they didn't learn from Mrs. Grabowski in fourth grade as revisionism and woke propaganda. Wokeism in the history sold to the public is real, but that's not what's written by actual trained historians, and trained historians’ work isn't part of that problem. A large part of the problem is that US history early became known as a biased field full of racist white guys, and we have been trying to shake that reputation ever since.

William Dunning later admitted he hadn’t done a good job in his hastily-written book on Reconstruction, history not really being his thing. A bit bloody late by then, wasn’t it?

The End of the Beginning

If you were educated in America until recently, the inept Dunning and his deceptive followers are almost certainly in your head. Real, dedicated historians have long been trying to root them out, with increasing success. But time is running out for us, because history is under attack from left and right.

In 1935, in his book Black Reconstruction in America, Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote: “We shall never have a science of history until we have in our colleges men who regard the truth as more important than the defense of the white race, and who will not deliberately encourage students to gather thesis material in order to support a prejudice or buttress a lie.”

We no longer think history is a science, or that historians are all men. But the vast majority of historians, regardless of our ethnicity or identity, would otherwise now agree wholeheartedly with Dr. Du Bois. Trouble is, fewer and fewer of us are being hired in universities. Some of us have left campus (I was one of them). At a recent meeting with historians, someone asked hesitantly, “Is it time to leave academia?” I coughed pointedly. Historians who are hanging on are now afraid of being fired for upsetting someone with facts.

I have a book on Dunning and his followers on the way to me in the mail. If you want me to pursue this subject again sometime and in more detail, please “like” or comment. Meanwhile, we’ll move onto pastures new. Oh, wait! I almost forgot! What and who inspired me to write this post?

A Long Time Coming (but change is gonna come)

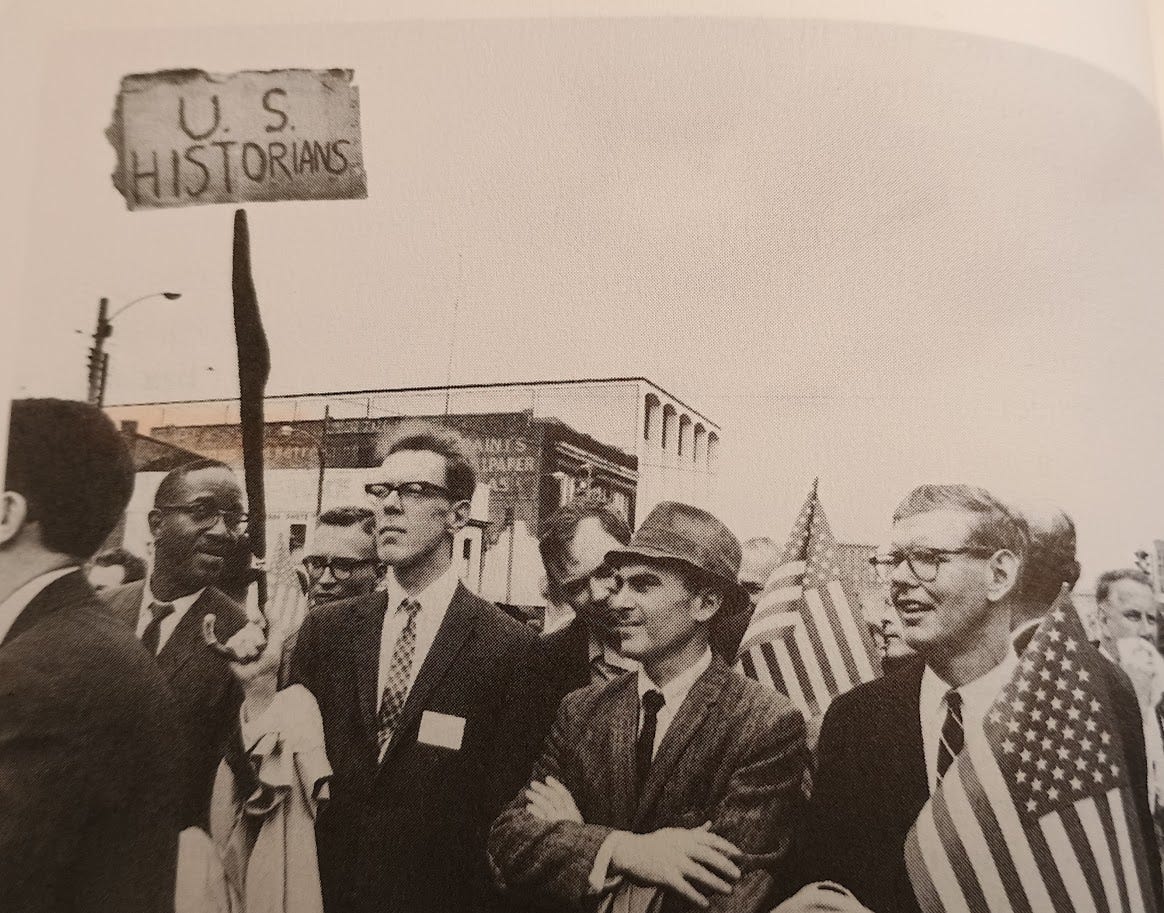

Reading School Book Nation (2003) by Joseph Moreau, a history of US history textbooks, I came across this photo. I teared up when I realized what it meant. I mean, just look at them: A half dozen historians on the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march in 1965.

Look at their crappy homemade sign, obviously an afterthought, because historians aren’t interested in wasting time on fancy signs.

Look at their dorky little historian faces, all six of them, marching in two mismatched rows, most of them in glasses! All were distinguished scholars, but, for the sake of time, I’m only going to mention three:

On the right, there’s Dr. William Leuchtenburg, holding a flag. He was the leading historian of FDR and the New Deal. Dr. Leuchtenburg lived almost forever: I recall seeing his name on the board of a great nonprofit, the Living New Deal, and doing a doubletake: How can he still be alive, I marveled? Sadly, Bill Leuchtenburg finally left us in 2025, at age 102.

The tall guy carrying the crappy sign? That’s Dr. John Higham, WWII veteran, scholar of immigrants and immigration, and professor of history at Johns Hopkins University.

A bunch of white guys? All but one, and the reasons for that include everything I just wrote, and more. Last time I met a bunch of historians, last month, I was the only woman in the crew, among about a dozen of us, all but one of whom were white (the other being a Native). Yes, that can still happen, but not often these days. I did not have the easiest time in the profession as a mouthy female Brit, but that’s a massive story that’s not as simple as you might guess, and notice how I still show up. I owe the fact that I’m a historian at all to a bunch of guys, including the man on the left of this 1965 group. That’s Harvard PhD John Hope Franklin, distinguished historian of African-American history.

John Hope Franklin wrote From Slavery to Freedom, the first book I ever read on American history. I ran into him at the AHA’s annual meeting, decades later, and made an arse of myself, telling him with a bow that I was not worthy. He laughed uproariously, and was so kind when I told him why I owed him: I later discovered he had once met his hero, W.E.B. Du Bois who had reduced him to a puddle of embarrassment, so no wonder he didn’t do the same to me.

Now, in a short section of Joseph Moreau’s School Book Nation, I just learned a little of Dr. Franklin’s story: Born in 1915, he had taken a lot of crap to be a historian. The son of a lawyer in Oklahoma who barely survived the destruction of Tulsa’s black neighborhood by a white mob, Franklin earned a PhD in history from Harvard. His adviser was Samuel Eliot Morison, a white Northern liberal who—like almost every white historian of his generation—had bought into the tripe peddled by Dunning’s followers, writing in a textbook with his historian colleague Henry Steele Commager (I mentioned him in my last post) that enslaved people were happy. I can only imagine the painful interactions between Morison and Franklin, professor and student.

When he was working in the Library of Congress, John Hope Franklin had to turn down lunch with fellow historians because the only restaurant in the area did not serve black people. He was turned away from archives in the South. He was treated like an idiot. To stay sane, he wrote about his anger in essays he did not publish. But he had a job to do, and he kept hammering away at the misrepresentation of history, including Reconstruction. In the 1950s, as the Civil Rights Movement took off, Dr. Franklin broke from black historians’ boycott of the white profession that had snubbed and demeaned them, by joining the AHA. He found young white colleagues, like the men in the photo above, who were supportive of his cause, which he modestly described as “to weave into the fabric of American history enough of the presence of blacks so that the story of the United States could be told adequately and fairly.”

By 1979, John Hope Franklin was president of the AHA. He damned the torpedoes from skeptical black historians as well as racist white ones, and went full speed ahead. But the damage of the early twentieth century is still playing out in ways I haven’t time to unpack. There’s also a lot more to know about John Hope Franklin—I hadn’t realized he wrote two memoirs. But I wish I had known more thirty years ago, as I fought my own battles, and I very much wish I had known him. I’m still grateful to the late Dr. Franklin for his kindness during our long -ago brief encounter. I look at that photo from the Selma to Montgomery March, and I think, well done.

Find Out More from Annette at NBH

Read more at Non-Boring History about the early historical profession and the corruption of Southern history, just one of many subjects historian Annette Laing chats about. EVERY post is unlocked to you when you’re an annual or monthly subscriber, like this one:

The Confederacy's Daughters Dance In Our Heads (1)

This tale begins with a story about a statue in a small town in Georgia.

Not ready to subscribe to Non-Boring History? Please chip in, and buy Annette a coffee (or coffees):

While I was an undergraduate at Louisiana State University in the early 1970s, I was fortunate to take a class on Black History - the first time it was offered - and read works by John Hope Franklin and Carter Woodson. It was eye-opening and refreshing and it scraped off the whitewash I had been fed in 12 years of Southern elementary and secondary school.