Eyes Right

ANNETTE TELLS TALES The American Revolution seen like never before: From the West. And it's fascinating!

Recent Highlights from Non-Boring History

When the Saints Come Marching In

Picture it, as Sophia used to say on The Golden Girls:

More than 1,300 armed men, camped near a river on swampy forested land in America. They were worried they would have to defend their homes against the British Army, and they came to hear what their colony's leader had to say.

This was September 7, 1779. The United States of America, Britain’s mainland colonies (not including those in the West Indies) had declared independence from Britain more than three years ago. But Britain wouldn’t take that nonsense off its American colonists. So war was still raging.

On this day, about half of those gathered here, 600 men or so, were official militiamen, the equivalent of today’s National Guard [UK Territorials]. They were ordinary guys, willing to fight for their homes under local government command.

Many of these particular militiamen were French.

Ah, you didn’t expect that, did you? But they were. There were two kinds of Frenchmen here: Some were Frenchmen who had lived in this colony for a long time. They held no love for the British Government, and neither did the other group of Frenchmen present, recent migrants evicted by the British from Maine and Canada’s maritime provinces (the Anne of Green Gables bits of Canada, next to the Atlantic).

About eighty other militiamen present were free black men, assembled in all-black units with their own officers. Like everyone else, they had their own concerns.

But wait, there’s more:

Some of the waiting men were British immigrants who had settled in America. They, too, were miffed at the British Government. They had agreed to settle a starter colony in eastern Florida, perhaps eagerly anticipating the opening of Walt Disney World in a couple of centuries. During the war, however, the British Army hadn't bothered to protect them when they were attacked by American rebels (aka Patriots). So, just last year, 1778, these hitherto loyal British expats had packed up and left in a huff. They had moved west, and, with this leader’s help, had founded a multicultural town along with Spanish people from the Canary Islands, naming it Gálveztown.* They, too, were anxious to hear what the leader had to say on this day.

*It no longer exists. Not to be confused with Galveston, Texas, but named for the same dude, more about this shortly.

Oh, and a hundred and sixty of the armed men awaiting the leader’s announcement were Native warriors, Choctaws, Alabamas, and more.

Only a tiny group of militiamen, just seven of them, arrived for the big announcement marching behind an American flag. They were led by Oliver Pollock. He was Irish, born and raised a Protestant in Northern Ireland. Keep an eye on Oliver Pollock. Although officially a British subject, he didn't much like the British either. But that American flag doesn't tell you his agenda. As we shall see.

Wait, where exactly are we, Laing? Are they waiting on a speech from George Washington?

Hang on . . .

Also present , and ready to fight: Five hundred Spanish Army soldiers. Yes, Spanish soldiers. As in professional soldiers. Who are from Spain. You’re not reading this wrong.

On September 7, 1779, all these men were waiting on an address from this leading military man, who was also the leading civilian present:

Laing, that's not George Washington . . . Is it?

No, he’s not George Washington. Meet Brigadier General Bernardo de Gálvez!

General Bernardo de Gálvez is also Governor Bernardo de Gálvez. He’s the Spanish-appointed Governor of the formerly French colony of Louisiana.

Yes, Gálvez is Spanish. As in, he’s from Spain. And yes, we’re in Louisiana, with its colonial capital of New Orleans. Formerly owned by France, Louisiana is under new management. But it's still very much a French colony, with most free people identifying as and speaking French.

OK, Laing, I’m now very confused. Louisiana belonged to France. Not Spain. I mean, New Orleans is very French, even now. All that cafe au lait and laissez le bontemps rouler and whatever. US President Thomas Jefferson later bought Louisiana from France, I remember that much from high school. What were the Spanish doing, owning Louisiana in 1779?

Oh, Louisiana is way more complicated and interesting than most of us realize. Louisiana was indeed founded by France. However, in 1762, seventeen years before this meeting near the river, France’s government had quietly transferred ownership of Louisiana to their Spanish ally.

Sure, France later got its colony back again from Spain, so yes, Jefferson did indeed buy the massive original Louisiana from France, but that’s not our story today. Nobody knew that would be Louisiana’s future, not in 1779.

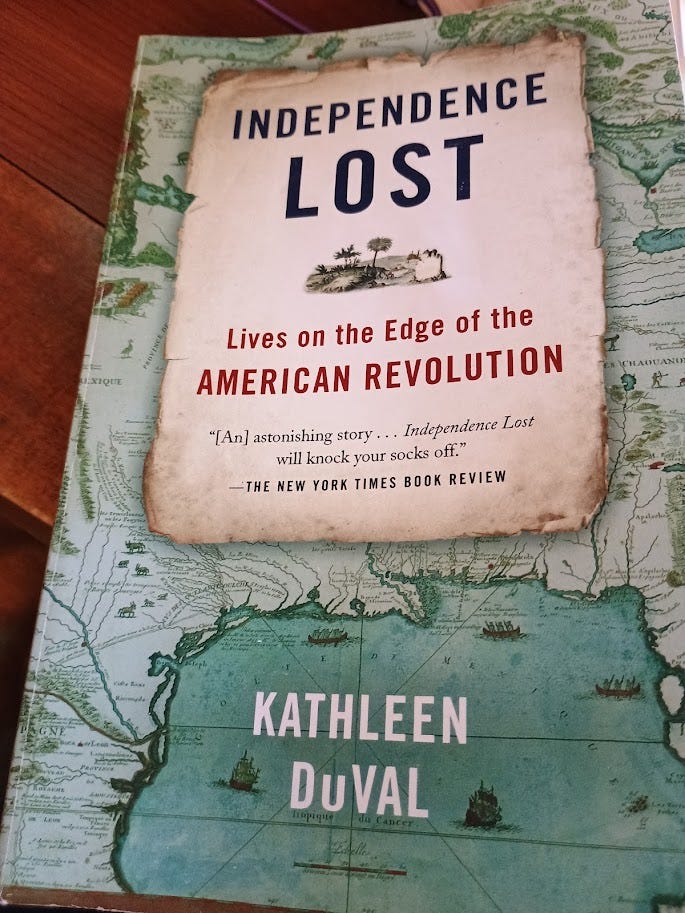

Today, I’m riffing on just one part of one chapter of an astonishing book, a work of scholarship that’s also aimed at the public (meaning it’s readable by at least some normal non-historian people). It’s called Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution, and it’s by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian (as of 2025) Dr. Kathleen DuVal, who published this earlier work in 2015. Now 2015 is recent in historian terms, but it’s long enough ago to have showed that this book is aging well, like a fine wine, unlike some more recent books that appear to be headed toward vinegar.

If you’re a non-US reader, grab some popcorn and relax. Oh, wait, no, grab the popcorn, open a modern map of the US southeast in a window on your screen, and THEN relax!

Where Are We?

So you’ve got a modern map of the US Southeast on your screen. Now here’s a map of the region we’re talking about today, as it appeared (more or less) in 1779:

Now the learning curve may feel steep here, as you cast your eyes on this map, so just take your time. Don’t worry too much. Looking at this map will help, I promise.

Note part of Louisiana on the left, and especially note New Orleans, near the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Note also that there were two Floridas by 1779.

At the conclusion of the Seven Years War (AKA French and Indian War) in 1763, sixteen years before our meeting in the swamps, Britain had won Florida from Spain. The British had then divided Florida into East and West Florida. East Florida would eventually become the Florida That Brits Like, with Disney World and all that. A coincidence? Or not? You decide.

West Florida now included Pensacola, a city that had been named for one of the Muskogean-speaking indigenous peoples on whose land the Spanish set up shop. First settled in 1559 (well before the English showed up in Virginia in 1607), Pensacola was smashed by a hurricane, but later re-established in 1698.

Britain also got the Florida Panhandle. For those of my readers for whom this is mystifying, look at your modern map: If the dangly bit of Florida were a weird pan shaped like a sock, the panhandle would be its handle. The bit sticking out to the left.

Wait, there’s more! This Florida extended much farther west than does Florida today (check your modern map). British West Florida also included the eastern coastal bit of what had been French Louisiana: Today, we’re talking the lower reaches of the states of Alabama and Mississippi, which of course hadn’t yet been invented. Don’t sweat this: Just take a look at the map above, and compare with a map of the American southeast today. It helps.

Look at our historical map again. The area broadly north from Fort Toulouse is the northern bits of what’s today Mississippi and Alabama. The site of Fort Toulouse is now Wetumpka, Alabama, if that helps, and it’s a very nice little town to visit. The Poarch Band of Creek (Muscogee) Indians still live there, and they will be delighted to welcome you to their fabulous resort hotel/casino, Wind Creek. No, that was not a paid placement. I don’t do those. In 1763, this entire area, and extending into Georgia, was still recognized as belonging to the multicultural Creeks and other Indian nations. It was not a reserve or reservations as the map says.

If you’re still bewildered, relax. Just keep glancing at the map above and the modern map you’ve opened for reference. You’ll get the hang of it, your reading will make way more sense, and you’ll be glad you stuck with me.

Now we have geographic context, let’s get some idea of what a big meeting in a swampy bit of Louisiana (not to mention Florida) has to do with the American Revolution, and why even Disney fans might find this interesting. So, as they say at Disney World:

Howdy, folks! Please keep your hands and arms inside the train, and remain seated at all times. Hang on to your hats and glasses, because this here’s the wildest ride into historiography!

History Changes

Laing, what does Florida have to do with anything? Why are we involving Louisiana in the American Revolution? Why wasn't this taught to me in high school?

Um, because this history hadn’t been written yet. As historians do, Dr. Kathleen DuVal raised this and many other astonishing stories from documents in archives. But there’s more to why you didn’t learn about this: If you’re a longtime reader of Non-Boring History, you may recall that early American history started with blokes at Harvard and other New England universities, most of them New Englanders themselves, studying New England. That’s why we got the impression that the US started with the Mayflower.

But early American historians in my lifetime, and especially since the 1980s, spread out to pay attention to Virginia, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, the Carolinas, Georgia, and wait, there’s more: The places that people came from, including Britain and West Africa, and, holy cow, what were the Spanish up to? They were here before the Mayflower, and not just in the West, but in Florida . . . And what’s an early American historian doing studying China?? Early American history just rebranded itself as Vast Early America. You can see why.

Meanwhile, old historians, historians (the majority) in exploitative university jobs that give them little time to read books, schools, museums, and most of all, the public struggle to keep up. Alas, except for historians and professionally-run museums, a lot of people are skeptical when historians write about new things. As the late legendary historian Dr. Joyce Appleby (herself an old-school scholar of politics in the early American Republic) put it in a talk I attended at UCLA, wearily removing her glasses, “People think that if we tell them something they didn’t hear from Mrs. Grabowski in 4th grade, we’re lying to them.”

We’re not lying to you. As I am working hard to show you here at NBH!

So what about that astonishing scene in the Louisiana countryside in 1779. How did that happen?

Perhaps you're American, and have always thought the American Revolution happened exactly as Mrs. Grabowski, or Coach Grunt, your history teacher/football coach, explained it in high school (Lexington, Concord, Paul Revere, Betsy Ross, George Washington, etc). Maybe you’re a Brit or Australian or Kiwi or Pakistani, and never really learned about any American history except from Westerns and vague references to the Mayflower. Or perhaps you're a Canadian who knows more than you're letting on. Whatever you are, I’m pretty sure that today is new to you. As it was new to this early American historian.

Let’s get some context. Let's talk about Louisiana in the middle of the 18th century. Let’s leave our gathering in a remote area waiting to hear Big News in 1779. Let’s pop back to 1763, and zoom out to see how we got here from the much bigger perspective of the global stage. Again, hold onto your hats and glasses.

Nobody Expects the Spanish

To recap, France lost the French and Indian War (the name for the Seven Years War in America) to the British (which included Britain’s American colonists at this time). In 1763, in the agreement ending the war, Britain now confiscated most of France’s colonies, including eastern Louisiana. Note that Louisiana was a lot bigger than the modern state, and France hung onto most of it. France was allowed to keep western Louisiana, including New Orleans and its access to river and sea.

Spain, like France, also came out of the war badly. Sure, the Spanish still owned most of what’s now the western United States, like Texas and California. But Spain lost Florida, its only holding on the Atlantic coast, to Britain. The Brits now divided Florida in two. Why? Because it was big and sprawly, and they wanted to make it easier to manage, even as the Spanish settlers packed up and moved to Cuba, because Brits were moving in. They were waiting for Disney World to open, remember? Okay, I made that up. Apologies to the late Dr. Appleby. Ahem.

BUT here’s where things took a weird turn.

French and Spanish representatives secretly met in France, and France secretly transferred ownership of Western Louisiana to Spain. Why did the French do that? To make nice to Spain at a time when the defeated French desperately needed allies. Why did Spain want Louisiana? Mostly because they wanted to prevent the British colonies from expanding West and threatening the Spanish bits of North America: Like what’s now Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, all of it mostly a buffer zone to protect Mexico and the other important Spanish bits from French Louisiana. But the Spanish had plans. They were already busily planning to colonize California. And now they owned the best bit of French Louisiana, and had a chance to get Florida back.

There was a slight problem, though. In making their secret decision, neither France nor Spain had consulted with the French people who actually lived in Louisiana.

Bienvenue, Les Amis! And Top of the Morning to You!

Deep breath. Let’s meet the Cajuns.

Louisiana’s French majority not only included longtime French settlers, but also Acadians (eventually shortened to “Cajuns”). Acadians were formerly colonists in the Canadian maritime provinces (Atlantic coastal bits), plus Maine. The British up there had given them the boot.

After they were evicted from Canada and Maine, Acadians had taken France’s suggestion that they move south to sunny (and French!) Louisiana. Bienvenue, les amis! The Acadians settled down in the French city of Baton Rouge. Unfortunately for them, Baton Rouge, which was in a prime location near the Gulf Coast, suffered frequent changes of ownership. Suddenly, Baton Rouge was now a British city (luckily, the Brits didn’t rename it Red Stick) and the Acadians again got eviction papers. We should not be surprised that the Acadians now moved to the swampy countryside, where rivers served as roads. For all you Hank Williams fans out there, the Acadians came to call these slow rivers bayous, a word which isn’t actually French, but based on the Choctaw word for little stream. There, the Acadians hoped not to be bothered by anyone. Ha! Good luck with that.

When the “secret” was inevitably revealed of France’s transfer of Louisiana, the Acadians discovered that they now lived in Spanish America. They were outraged, and so were the original French settlers in New Orleans.

Given all this French unhappiness in Louisiana, you may not be surprised to learn that when the first Spanish Governor arrived in New Orleans, angry Frenchmen gave him le boot.

Spain thought about this, and, in 1769, sent a new, tougher, governor to replace the first guy. This new governor was Irish. Yes, Irish. The new governor was, to repeat, Irish. He was an Irishman who had become a naturalized Spaniard, and he was a leading Spanish soldier. His name was Alejandro (originally Alexander) O'Reilly.

Governor O’Reilly, a very competent soldier and civilian administrator, accompanied by Spanish soldiers, quickly imposed Spanish law on the no-doubt confused people of Louisiana. In gratitude, the King of Spain named him Count of O'Reilly. Which is fun.

Anyhoo. O’Reilly was long gone by the time of our encampment, in 1779. He was off on new adventures, like becoming known as the “Father of the Puerto Rican militia”. But I didn’t just introduce him for the amusement factor. O’Reilly, an Irish Spaniard running an American colony full of Frenchmen, is just one hint of how complicated and diverse American history can be. And we will meet him again in a little bit.

Much of American history involves many, many people who didn’t claim to be American at all. Not even during the American Revolution. Not even three years after American Independence was declared on July 4, 1776.

Back to that Gathering by the Bayou, 1779

So let’s return to September 7, 1779, to that encampment of armed men, near the Iberville River, in Now-Spanish Louisiana. Everyone was waiting to hear what the latest Spanish Governor, Bernardo de Gálvez, had to say, and to then decide what they were going to do about it.

This is the American Revolution. However, the men gathered, whether Irish, African, Spanish, Spanish-from-the-Canary-Isles, British, Alabama, Choctaw, French, or whatever, didn't know that yet. They were in future bits of the United States, but they could hardly know that, either. They were not even members of the British colonies. They lived in a colony owned by the Spanish Empire. And apart from the Spanish troops with Gálvez, they were not from Spain. They had come to this meeting for many reasons, but above all, they were here on the side of their homes and families.

They waited to hear what Governor Gálvez had to tell them, what he wanted from them. They already knew the King of Spain had recognized the United States, but what did that have to do with them? They weren’t British colonists rebelling against Britain. They weren’t even Spanish. The Frenchmen in the crowd were not even sure that Louisiana would long remain under Spanish management: If they had their way, it wouldn't, and Gálvez would get le boot.

Gálvez needed these men more than they needed him. He was keenly aware that every Spanish governor of Louisiana depended on the respect and cooperation of the French people who lived here. He had already had an encouraging reception for his speech from the urban French in New Orleans, but this diverse group in the countryside was a whole other crowd.

Addressing this crowd of 1,300 was a challenge for Gálvez. He did not, of course, have a microphone. He just had to yell to 1,300 men. And he was yelling in Spanish at people who spoke little or no Spanish. Fortunately for him, bilingual translators were sprinkled through the crowd, interpreting the Governor’s words from Spanish into French, English, and at least three Indian languages, while the Canary Islanders who spoke Spanish, but who were a bit like people from Glasgow listening to someone speaking Cockney dialect, tried to follow the gist. If Gálvez had simply told them all flat out, “Spanish is now our official language, folks, so just deal with it if you haven’t bothered to learn it yet” he could not have been understood, much less won anyone over.

With the help of translators, though, everyone heard the amazing news from Gálvez: It was official. The King of Spain had not just recognized the United States, as everyone already knew. His Majesty King Carlos III had declared war on Britain! Everyone in Louisiana must now do their bit to protect their homes from the Brits! And yes, he was also talking to the Brits who lived in Louisiana.

How Gálvez won over these men is interesting, but for now, let’s just say he did. These ordinary men from many places decided by common acclaim that they would fight for Louisiana, for their own continued prosperity and independence.

Having persuaded the crowd to fight against Britain, it was Gálvez’s further burden to convince them—and keep them convinced— not to fight for the United States. He needed to persuade them to agree to stick with the Spanish Empire, to remain loyal to Spain, yes, even the French guys. And he did that. For now. Subject to change without notice.

Mission accomplished—for now— Gálvez rode around the rest of Louisiana, speaking as he went, to convince and recruit more men, free and enslaved, Black, British, French, Irish, Native, and more to Louisiana’s militia. Gálvez had prepared for this challenge under difficult and changing circumstances, and he succeeded. He persuaded Louisianians that their best bet was to live under the protection of the Empire of Spain.

At least for now. Subject to developments.

Just as people in Britain’s colonies had to decide which horse to back, which side to support, based on their own interests, so did the people of Spain’s unlikely colony, Louisiana.

For now, the armed men to whom Gálvez had spoken were enthusiastic subjects of the Spanish Crown. They included even those Brits who had relocated from Florida, the Brits whom both Walt Disney and Britain had let down, and who now lived in a town they had founded with Canary Islander neighbors, a town they had named for Gálvez, the Spanish governor, in gratitude for his welcoming them as asylum-seeking refugees.

American readers, I now want you to form a mental map of 18th century colonial America (or whatever you can recall from high school). Maybe you're thinking Boston, or Philadelphia, or even Savannah. Maybe you're just thinking “East Coast”. Now, in your mind’s eye, move West. Ah, the Appalachian Mountains! A barrier that was less geographic than it was political. The British Government had forbade colonists to settle beyond these modest peaks, because otherwise they would need to be defended from hostile Indians at great cost, right? I bet my American readers vaguely remember this.

Think of American colonists, all tricorn hats and mob caps. They didn't yet think of themselves as Americans. They identified with their individual colonies, like Virginia or Massachusetts. And many also still thought themselves British, or were open to doing so, after 1776. That alone is tough for you, isn’t it, because I doubt even Coach Grunt knew that (or much of anything, tbh).

Now, I want you to imagine people west of the mountains, in New Orleans, and rural Louisiana.

I can't picture them. All I can imagine is people chucking beads at Mardi Gras parades, and Hank Williams singing Jambalaya (On The Bayou).

I get it. You didn't cover this in high school. But here we are.

All these people in Louisiana weren't really involved in the American Revolution, though . . .

Oh, yes, they were. They were pledged to fight Britain, so they were very involved. Don’t believe me? Dr. Kathleen DuVal has the evidence in her book, which I am happy to plug free of charge.*

*As always, I’m determined to remain exclusively reader-supported. In the past week alone, I turned down three offers of free books from publishers , and asked them to take me off their mailing lists. Why? Because as history shows, a gift, especially from a stranger, creates a sense of obligation, as it is intended to do. Advertising is even worse. The only people I feel obliged to are the paying readers who grasp that I’m trying to reach as wide a range of readers as possible, while inevitably offending all my readers at NBH with facts that contradict what they have always thought and/or want to think. Want to get all my posts? Want to help? Please do:

Introducing Oliver Pollock

When Governor Bernardo de Gálvez made that speech to armed men in the Louisiana countryside, at least one man in the crowd had already been tipped off about his shock announcement that Spain had declared war on Britain. This man also knew that Gálvez had orders from Madrid to conquer the Mississippi Valley and West Florida, ASAP. Irish businessman and local New Orleans resident Oliver Pollock had been the first to know all this intel, because he got it from his dear friend, Governor Gálvez himself.

How did Pollock know so much? Governor Gálvez considered import/export merchant Oliver Pollock reliably loyal to the Spanish Empire. Honestly, though, Oliver Pollock was most reliably loyal to Oliver Pollock, but we’re getting to that.

Well before that September day in 1779, Governor Gálvez had to weigh the potential consequences of making an announcement about going to war with Britain on behalf of the Empire of Spain. Would Louisiana’s colonists, most of whom were French, get on board or show him the door? Would the Brit minority in New Orleans turn on Gálvez, and tip off their fellow Brits in West Florida? Before making his news public, Gálvez ordered a discreet study of how many potential militiamen might be available to him in each area of Louisiana. He also began quietly improving New Orleans’ defenses.

How can you build defenses quietly, I asked myself? No clue. I tried to imagine awkward conversations between the builders and passers-by: “What, this building into which I am hammering nails? Ooh, it is a new McDonalds I’m building, mon amie! It just happens to be shaped like a fort!”

Gálvez was also discreetly buying ships (presumably from a man down the pub) to carry soldiers to the east, to invade West Florida from the Gulf of Mexico. He held meetings with Indian leaders, including Chickasaws and Choctaws, in which he implored them not to fight on the side of Britain.

Now, it was showtime. It was September 3, 1779, and men were waiting at the encampment for Gálvez to address them. Oliver Pollock of New Orleans, the Irishman whom Governor Gálvez first let in on the secret news, was one of the seven guys who arrived waving an American flag. In the interests of full disclosure, Pollock should probably also have waved a little flag that read “Make Oliver Pollock Great Again.”

Who was Oliver Pollock? What did he stand for? Depends which day we're talking about.

Oliver Pollock was a Protestant from Northern Ireland. That made him a British subject, with all the rights and privileges of such. But he had a mixed marriage: His wife, Margaret, was an Irish Catholic, fiercely opposed to British rule of anywhere, really. Together, they were a remarkably well-traveled couple.

In 1779, the Pollocks lived in New Orleans. They had moved to Louisiana in 1768 from their previous place of residence—Havana, Cuba—without having planned to.

See, Oliver Pollock showed up in New Orleans shortly after the arrival of the very competent Spanish Governor O’ Reilly. Pollock’s arrival was a stroke of luck for O’Reilly, who had been friends with the Pollocks when he was posted in Cuba. Pollock’s arrival in town was an answer to O’Reilly’s prayers. That’s because he needed help purchasing food for the Spanish soldiers under his command, the men who would back up his authority in a fractious French colony which had already sent his predecessor packing.

Under the touchy circumstances, forcing locals to host alien troops for dinner would clearly have been a very bad idea, something the British were finding out in their American colonies.

But it just so happened that Oliver Pollock landed in New Orleans with a ship full of flour for sale. And, yes, he would be more than happy to sell the whole lot cheap as a favor to his old friend Governor O’Reilly! O’Reilly promptly gave Pollock the exclusive contract to feed his troops.

What’ s more, in return for Oliver Pollock’s not jacking up his flour prices, as a favor to his friend, O’Reilly made him a great deal unlike any other in New Orleans: Free trade.

That meant Oliver Pollock, and only Oliver Pollock, based in the Spanish colony of Louisiana, could buy from and sell to British American colonies directly, without the usual routine of sending the goods first through Spain or Britain, where they would be taxed.

Basically, O’Reilly gave Pollock a license to smuggle.

This was awesome. Pollock went all in, moved his business HQ from Cuba to New Orleans, and converted to Catholicism as a sign of his devotion to the Spanish Empire. I suppose this also meant that he and Margaret could go to church together on Sundays. Anyway. The Pollocks were soon very rich, trading sugar, tea, rice, wheat, fabrics, and much more, like an early Amazon.com, up and down the Mississippi Valley, to the Caribbean, and across the Atlantic.

But Oliver Pollock was also still a Brit, from Northern Ireland. Then as now, Britain didn't allow its native-born peeps to renounce their status. That allowed Pollock to trade directly across the border with West Florida, and that he did, selling tobacco grown by enslaved Africans in Louisiana, plus deer and beaver furs purchased from Indian nations. Pollock also became his own supplier: He became a landowner and slaveowner, buying and employing enslaved Africans in producing food and tobacco for New Orleans, Pensacola, and beyond.

Neither Oliver nor Margaret Pollock, being from Ireland, had any love for Britain, where they had never lived. And they were open to new business opportunities, like those opened up when the mainland British colonies—in which neither of them had ever lived, either—rebelled against London.

The rebelling British Americans, Oliver Pollock reckoned, would need Spain’s help in getting war supplies. And his Spanish Empire connections, first with Governor O’Reilly and soon with his new friend Governor Gálvez, made Oliver the perfect the go-between, in his view. This could be huge, especially for Oliver Pollock.

Oliver Pollock made it happen for Spain to send money to the American rebels to finance their war. The Continental Congress, staffed with representatives from all the rebelling colonies, was basically a giant committee that was running the war effort. The United States Congress appointed Pollock as its business representative in New Orleans in 1776.

Oliver and Margaret Pollock were now increasingly heavily invested in the success of the American Revolution.

In 1776, Oliver Pollock rented a ship for $1000 just to send a letter accepting his Congressional appointment as trade rep, and to congratulate Congress on declaring independence. Congress, thrilled to have their obviously rich and successful Man on the Ground in New Orleans, sent Pollock a purchase order for $30,000 or so worth of supplies for the Continental Army and its Indian allies. He soon shipped them hundreds of shirts, hankies, stockings, and shoes, plus booze for the army officers, and much more. And, of course, Oliver Pollock sent his bill. Now he waited to be paid.

By 1779, three years and many ships and bills later, America and Britain were still at war, and Pollock did not feel quite so optimistic. His connections to the not-yet-officially-independent United States were, shall we say, a mixed blessing at best by 1779.

A Perfect Storm, 1779

On August 18, 1779, just weeks before our encampment in Louisiana, and only days after Oliver Pollock’s chat with Governor Gálvez about the pending announcement, a hurricane was bearing down on New Orleans. In those days before modern weather forecasts, the first you knew about the approach of a devastating storm was choppy seas and strong winds. The Pollocks saw the signs, and hastily rounded up their kids, important documents, and a few knickknacks, and headed north, away from the coast.

Among the documents Oliver Pollock grabbed on his way out the door were a bunch of receipts, the only proof he had that the Congress of the United States of America owed him a fortune.

The hurricane did indeed slam and devastate New Orleans, as Gulf hurricanes tend to do. The ships that Governor Gálvez had quietly ordered for his invasion of West Florida were destroyed. Instead of building defenses for New Orleans to defend it from the British, men were now employed rebuilding their smashed home city to make it worth defending.

Two days after the storm, Governor Gálvez had to address the people of New Orleans—this is two weeks before his speech to the encampment— to persuade the men of the city, most of them French, to put down their hammers, pick up guns, and go fight for the interests of the Empire of Spain.

Oliver Pollock watched his pal Governor Gálvez make that first pitch in what’s now Jackson Square in the French Quarter of New Orleans. This speech was quite the gamble: The city council were French. Most of the men in the square were French. Even Governor Gálvez’s Lieutenant Governor (deputy) was a Frenchman. They all saw Spanish control of the city as a temporary inconvenience at best, and often muttered rebelliously about kicking out the Spanish. What hope did Governor Gálvez of getting a foothold in the city for his grand plan?

To recruit Frenchmen, Governor Gálvez focused on what they had in common with the Empire of Spain: Money (economic interests), Catholicism, and hating the Brits. Support for the United States? Um, whatever, not really. This was all about defending their Louisiana homes in time of war. The King of Spain had named him Brigadier General to lead the military campaign, he told them, as well as permanent Governor of Louisiana. For both appointments, he told the crowd, he had taken an oath to defend Louisiana.

However, he said, he could not keep that promise unless he knew he had the support of the people. He needed their help to defend Louisiana! Note that he didn’t emphasize how their support would benefit Spain.

Brilliant. In one instant, Governor Gálvez had won the support of the mostly French people of New Orleans. Now he had to tour the rest of the region to build on that support. That’s what brought him to that riverside encampment in September.

Among the men who rode into the countryside with now-General Gálvez was his buddy Oliver Pollock. Pollock was more used to travel by sea, and riding a horse through trees and swamps was literally a pain in his bum. But he was eager (and anxious) to do his bit to make sure things went the right way, his way. He was sure, he wrote unconvincingly, that Gálvez would “soon reduce the British troops, Tories [British Loyalists] and savages [Indians who were on Britain’s side, as opposed to Indians who worked with Gálvez and did business with Pollock]” He certainly hoped so. He had a lot of money riding on the outcome of this war. If Spain beat the Brits, the British Americans might also win, or at least win enough to pay him back. If the United States lost to the Brits, he was going to debtors’ prison. I bet Pollock waved that American flag as hard as he could.

Premature Celebration in Philadelphia

Washington DC was not yet the US capital, and the distinctive US Capitol building also lay in the future. The War for American Independence (aka Revolutionary War) had not yet been won in 1779, and despite French support, not to mention Washington’s military victories, nothing was guaranteed.

The Continental Congress of the US, and thus the US capital, was in Philadelphia (for the moment). Congressmen were meeting in a grand building they had borrowed from the Pennsylvania State Legislature, now called Independence Hall, because it’s where the Declaration of Independence was signed. War had already forced Congress to move from New York, and they would need to move again before peace came. I’m sure they kept go-trunks near the door.

Congress was not the two-house legislature of today, and there was no President under the Articles of Confederation, the original Constitution of the US (yup, another story!). That’s because most British Americans were deeply opposed to any form of government resembling Britain’s king-in-parliament model, because of the trouble London had given them. So there was just one single legislature, Congress, and it was financing and running the War by committee (all of Congress) and sub-committees. Of course, the United States won in the end, but whether that was because of or despite that very democratic form of rule, I am not about to suggest.

Want to read more about the Continental Congress at Non-Boring History?

Now, in Philadelphia in 1779, Congress was thrilled by the news: Woot! The Spanish Empire had recognized the US! That surely meant that even Spain was now confident that the plucky British colonies would win their war! And, best of all, Spain had now itself declared war on Britain. All that was left was for Spain and the US to sign a treaty of alliance on the dotted line!

Thomas Jefferson dashed off an excited letter to Governor Bernardo de Gálvez in New Orleans, whom he now saw as an important friend and ally.

Thing is, um, Jefferson and Gálvez had never met, and did not share the same goals. Jefferson and the rest of Congress desperately needed Spain and France to finance their war for independence from Britain. Spain, however, only needed the plucky British-American rebels as cannon fodder, to distract London from what the Spanish were up to as they extended control of the South. Just think! Instead of “Hey, y’all”, the entire Deep South could be saying “Hola!”

Jefferson didn't get it. His letter to Gálvez, although written in his capacity as a Congressional representative, was actually a begging letter on behalf of his very own state of Virginia, which was his priority, because the whole United States thing still seemed a bit unreal even to him, the man who authored the US Declaration of Independence. Jefferson asked Gálvez to send more than $65,000 (a fortune) to Virginia so his state could buy war supplies. Since PayPal, Venmo, and even bank transfers had yet to be invented, he asked Gálvez to send the money via Congress’s middleman in New Orleans. That middleman, of course, was an Irishman named Oliver Pollock.

In his letter, Thomas Jefferson promised Gálvez that he would repay Spain in wheat flour, except um, well, Virginia had had a bad harvest, plus they couldn’t send beef from their many cattle because of a salt shortage, so they couldn’t preserve meat for the journey, but let's figure out something down the road, ok? Meanwhile, if Gálvez could kindly use his influence with the Spanish King, and if King Carlos could see his way to making a loan, Jefferson suggested, the US Congress could really use another, um, five million dollars. We’ll pay it back. Honest.

Five million dollars? In 1779? Oy. Massive money. But Spain was willing to loan money to the new USA, because, well, it wanted help getting back Florida. Congress was willing to send soldiers to recover St. Augustine, maybe even Pensacola, using money borrowed from Spain. However, when Congress sent a team to ask their military commander, General George Washington, for advice on this proposed deal, Washington squashed it.

Look, guys, I’m sure Washington didn’t say in quite these words, we are going to have serious difficulty defending North and South Carolina and Georgia from the British, and you want me to take our boys where? Florida? The oranges place? Alligators? Swamps? Potential for theme parks after electricity and mass tourism are invented? Are you insane?

Washington offered his own deal proposal. He told Congress he wanted Spain and France to send soldiers and ships to ensure that he could hang onto the Carolinas and Georgia. Once those colonies were safe, he could maybe go fight for the future of Mickey Mouse.

In a letter, Thomas Jefferson presented General Washington’s counteroffer to Governor Gálvez. But Spain was not interested in Washington’s proposal. Look, Jefferson, I’m certain Governor Gálvez did not write back, we’ve got our backs to the wall with this expensive war with Britain, including in recovering West Florida. No, we don’t have money to send you. Please take us off your mailing list.

The US Congress now sent John Jay all the way to Spain (by ship!) to negotiate a treaty of alliance with the Spanish government. You would think this was a quick and easy job, just written confirmation of what Spain had announced. But no. King Carlos would not invite Jay round for dinner, or even invite him in for a glass of cheap sangria. Finally, Jay wangled a meeting with the Spanish Prime Minister, who told him bluntly that Spain would not even allow the United States free range for trade on the Mississippi River, which Congress had told Jay to demand. This was a war to make Spanish control in America stronger, not weaker, the Prime Minister told Jay, perhaps then suggesting to him he beg a cup of coffee from the cook in the palace kitchen before catching the next ship home.

What Jay didn’t know was that the British also had Their Man on the Ground in Spain at the same time, trying to negotiate an end to the war.

Complicated. To say the least. And it didn’t look good for the United States (still under construction).

Two Men in New Orleans Make Plans

Oliver Pollock, Irish merchant, and his pal, Governor/Brigadier General Bernardo de Gálvez, were each pursuing their own agendas by 1779, trying to make this whole American War for Independence thing work to their own advantage. Governor Gálvez imagined being showered with national glory in Spain when he was instructed to lead the Spanish defense of Louisiana, and the recovery of West Florida. He no doubt was well aware that former governor Alejandro O’Reilly had been honored with an aristocratic title for his services in Louisiana.

Oliver Pollock was concerned that the United States could potentially give him lots of massive economic opportunities, but only if it got its act together and won the war, and paid him what it already owed him.

Gálvez and Pollock had to work together, to pretend that the new relationship between Spain and the United States was on solid ground, in order to recruit ordinary men to the cause in the southeast, while also trying to persuade Congress to put on its big boy pants. They both wrote letters to that effect to Congress, and Oliver Pollock even helpfully translated Governor Gálvez’s letters into English for him.

Both men had reason to be concerned. But Pollock probably had the most reason to sweat. Right now, Congress and the state of Virginia were, to him, a bunch of deadbeats. They had yet to pay Pollock what they owed him for war supplies, and years were passing. This meant that Oliver Pollock wasn’t just a merchant: He was a war financier, doing much to keep afloat the War for American Independence, aka the Revolutionary War. Maybe we should pop Pollock’s face on a dollar bill? Hey, he allegedly later invented the $ sign.

And if the American rebels lost? Oliver Pollock would be in deep doo-doo. Let’s look at how that happened.

A Very American Coup

Two years earlier, in 1777, Congress had entertained a proposal to work with Governor Gálvez, and with British/Irish businessman Oliver Pollock, to invade British-owned West Florida, and end British trade on the Mississippi River, while opening the river to trade among the United States, Spain, and Indian nations.

But Congress had worried that this proposal could easily backfire, angering Britain's West Florida colonists, and leading them to take Britain's side in the War for American Independence. What’s more, the US was already short of cash and men: Taking and holding West Florida would stretch the US budget to breaking point. The proposal lost the vote in Congress.

But some Congressmen, led by Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, decided to launch the invasion anyway, by themselves, without Congress! So much for representative government!

Morris and friends approached James Willing, a posh Philadelphian whose merchant brother was Robert Morris’s business partner in Philadelphia. Willing and Morris (Inc.) just happened to be the firm that had launched the merchant career of one Oliver Pollock, and James Willing and Oliver Pollock had later partnered to open a shop in New Orleans. Let’s just say that Willing’s social and business connections were his most valuable asset to Pollock: James Willing was an alcoholic, and in debt.

James Willing: Perfect man to lead an illicit private military expedition, then! Morris and his allies in Congress told James Willing to board a ship called (I kid you not) the USS Rattletrap, grab the little British military outposts on the Mississippi, and seize the property of all settlers in West Florida who were loyal to Britain, preferably without violence, then go to New Orleans and get help and protection from Governor Gálvez and Oliver Pollock.

I’ll spare you the details. It didn’t quite go as planned, let’s put it that way. And Oliver Pollock was left holding the bill.

In 1779, Oliver Pollock was still waiting for Congress to pay him for the money he had spent on the Willing fiasco. To tide him over, meanwhile, Governor Gálvez had been loaning him cash. But now Gálvez had turned off the money tap, because he needed to hoard his funds to send his militia to West Florida. Gálvez had hoped West Florida would be handed off to Spain after Willing conquered it. Now, it looked like he would have to invade the place himself.

Oliver Pollock wasn’t just in this game for the money, well, sort of. He was happy to help the American cause. He saw a future in which British power was curtailed, and everyone—Catholic and Protestant, American and Spanish—could make lots of money. As Dr. DuVal notes, “part of American patriotism was the sense that it would be easier to get rich under the Americans than under the British.”

For now, however, Pollock 's glorious future seemed very remote. He had spent a lot of money and not been repaid by Congress or Virginia. He was having to mortgage some of his property to hold off his own creditors, and he wrote letter after letter creatively suggesting ways that Virginia and Congress could pay their debts to him, like by sending goods like flour and tobacco that he could resell in New Orleans.

A Congressional committee finally replied to Pollock after a long delay, making excuses, which I will now translate from Dr. DuVal’s translation of the original:

Dear Mr. Pollock Oliver,

Sorry this reply took us so long, but we’ve been slammed! We had to move our HQ out of Philadelphia in 1777, unexpectedly! We’re painfully aware of all the trouble and expense you’ve gone to for us, and we want to make things right. So we are finally going to pay you.

That’s the good news. Unfortunately, all we have to pay you with are Continental dollars, our useless US paper currency, but we hope you’ll appreciate the thought. Also, we hate to tell you this, and we do know you’re telling us the truth about what you have sent us, but, alas, none of the ships you sent us most recently, filled with goods, actually made it here. Three of them have been hijacked by the British, including the one with that character James Willing on board, so they kidnapped him. I guess they arent happy about his recent escapade. We hope you won’t miss him too much, ha ha. The other ships have just vanished. Yikes.

Now we think of it, we are happy to send you some of the money we owe you in wheat. Unless the crop fails. Like it did last year. But our wheat is looking pretty good from what we hear! However . . . Oops.

Unfortunately, it turns out, we can’t actually send you wheat, because there’s a trade embargo on exports, and we need the wheat to feed our Continental Army, and the French Navy who are helping us. Again, our apologies.

But hey, we’re Americans, so let’s think positive. Hopefully, there will be enough wheat so we can slip you some on the QT. You know, honestly, between you and us, we blame the American people for this embarrassing situation. Voters, eh? Tsk. They darn well need to agree to let us in Congress raise taxes to shore up our sinking Continental currency. Will they, though? Well we can all hope.

Love to Margaret, and big hello to Gov. Gálvez and everyone in the Big Easy from us,

Warm regards,

Your friends in Congress

As Dr. DuVal astutely observes, the American War began because Americans didn’t like being taxed. Voters weren’t likely to agree to more taxes. So funding the War for American Independence came down to printing increasingly worthless money, while flattering Congress’s creditors.

Pollock now wrote back, and pointed out to Congress that his mate Governor Gálvez had protected James Willing from the British, and should get something in return for his support. Could Congress send a few troops to guard the Mississippi, and maybe win back Pensacola from the Brits?

No, Congress said, we could not. We are broke. B-R-O-K-E.

Pollock had better luck dunning the State of Virginia for the money that it owed him. In 1780, Virginia sent him an IOU for $65,814, which was valuable only because it was guaranteed by France (and IOUs were basically what paper money was until the 20th century: Real money used to be gold, rather than imaginary stuff like paper and crypto). So, on the strength of his IOU, and by selling some of his land and enslaved people (think of the misery that caused, as families and community were torn apart), Pollock paid off some of his debts. Oliver and Margaret Pollock hoped their family home wouldn’t get repossessed.

Governor Gálvez, meanwhile, was not amused that he had not been consulted before the Willing expedition turned up in New Orleans. And now he learned that nobody in Congress had even read his letter of complaint about the Willing affair, because they couldn’t find anyone in Congress or, indeed, all of Philadelphia, who could read Spanish. This was gobsmackingly pathetic for an ambitious national government in the eyes of the Spanish.. Amateur hour.

To Gálvez and Spain, the lesson of all this was that the United States was an inept deadbeat wannabe nation, and not worth partnering with in wartime. And the Americans wanted West Florida for themselves? Ha! Like a country with no money, and an army that was largely made up, in Ben Franklin’s words, of draftees, of “boys, Negroes, and Indians” was in a position to take more territory? Please. After the War, even if the Americans won, Gálvez reckoned, the Spanish Empire could easily bully it into submission. Meanwhile, Gálvez would have to handle the British in West Florida by himself. It was worth the risk.

And Gálvez’s gamble paid off. Sort of. In 1779, the men recruited by Gálvez (and Pollock!) seized the cities of Baton Rouge and Natchez from the British. The way was clear for the Spanish to claim Florida, West and East. But while people in the multicultural city of Baton Rouge might get on board with the Spanish Empire, the city of Natchez, in West Florida, was a different matter. In Natchez, the British settlers were savvy and wealthy plantation owners, British Army veteran officers who got land grants there as a thank you for their service in the Seven Years War. They were careful to surrender to one Captain Pickles of the United States. Sure, they didn’t want to be British anymore. But they also didn’t want to be Spanish.

Even as Oliver Pollock and Bernardo de Gálvez clinked their glasses in celebration of getting Lousiana’s diverse peoples on board, they were celebrating different things.

If you enjoyed this on-ramp, I suggest you get yourself a copy of Kathleen DuVal’s award-winning and readable Independence Lost. The surprises keep on coming. By the time you’re done, American history will look more familiar, not less.

If you are Pulitzer Prizewinning historian Dr. Kathleen DuVal and you're appalled by any part of my riff on your work, please feel free to send a drone carrying a boulder to unleash your displeasure on Non-Boring House in Madison, Wisconsin. Alternatively, just send me an email.

This post is just one small part of the ongoing jigsaw puzzle that is Non-Boring History, as recovering academic historian Dr. Annette Laing interprets US and UK history on a wild ride that is far from trivia.

Become a Nonnie, a paid annual (best value!) or monthly subscriber to NBH, and get searchable access to more than 500 exciting posts, all future posts, and so much more. Plus you'll be a proud partner with Annette in bringing the insights of history to a bigger audience! Details here:

What great convoluted fun! Thanks!!

NBH is my favourite publication these days, and I’m busy pestering friends to take out paying subscriptions.

Your Canadian Fan,

Chris

As far as Coach Grunt goes, I was fortunate enough to have a few real history teachers in my grade and high school years. I owe them quite a bit. Luckily for me, they were able (to a certain extent) to teach me more than the "official" textbooks. One was in Puerto Rico, where I learned the real history of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. Hence my unconventional views about US policy. It was hard then to teach the "rest" of history. It's essentially impossible now.