Cheer Up, Charlie

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD A vulnerable soul wrestles with the carefully-curated museum of a renowned cartoonist

Annette on the Road posts at Dr. Annette Laing’s Non-Boring History are Annette’s takes not only as an academic and public historian, but as a historical tourist. She shows how she interprets museums and historic sites on the basis of the information in front of her, plus a little digging on the web, plus what prior knowledge she has, just as you do. That’s why these posts are a little more personal. New to Non-Boring History? Get oriented (or orientated, if you’re a Brit) at this post:

Note from Annette

This year’s Non-Boring History Summer Museum Bingo post is up! Print out the post, stick the card on your fridge, and play along!

Summer Museum Bingo!

Time for summer fun! And no, it's not just visiting typical museums, but broadening our definition of museums. :)

Recently, I amused the young women at the ticket counter of the Charles M. Schulz Museum. “Let me tell you when I knew I had become an old fossil,” I said, “and it was around 2012.”

It was a slow time, so they smiled encouragingly, and I carried on. “I saw a London play called The Last of the Haussmans. Julie Walters played the elderly and annoying hippie mother of a messed-up family, including adult children she had abandoned to go to hang out with some Indian guru. Walters came out on stage in a Snoopy T-shirt, holding it out in front of her, and said, Awww, Snoopy! My blood froze. I knew then that I was ancient. Past it.”

The girls laughed (I think they were amused, but if they were simply indulging me, Lord love them). It was true, though, this story: I had realized that expressing fondness for Snoopy or Charlie Brown already damned me in 2012 as frozen somewhere in the 70s or 80s as far as young people were concerned. Snoopy was a witch’s mark.

Honestly, I hadn’t read a Peanuts strip in more than thirty years. I had long ago decided it was time to put away childish things, to try to avoid the trap to which historians are especially prone, of wallowing in the past to the point of blind nostalgia. Or so I thought with that grave wisdom of someone in her late 20s/early 30s.

Now, as I arrived at the Schulz Museum, I really didn’t recall why I liked Peanuts to begin with. All I could recall was that Snoopy’s head is the only thing I’ve ever been able to draw to any kind of artistic standard (I was not blessed with talent in drawing, to my great regret.) I enjoy beagles, and I could say that Snoopy also gave me a lifelong love of beagles, but that’s not true. I mean, Snoopy wasn’t even a convincing dog, as I hope you’re recalling.

Mostly, what I recalled now was what seemed to me the tragedy of Charlie Brown, the nice kid who got crapped on all the time by his supposed good friend. Lucy was a nasty piece of work.

The Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, is dedicated to the cartoonist and writer who created the misnamed Peanuts cartoon strip. I’m not sure why I decided this visit was a good idea, but my long-suffering spouse Hoosen shared my interest in visiting, and we happened to be in Santa Rosa, and so off we went.

Here's the Museum entrance:

Well, count me charmed, and I wasn’t even in the door yet.

Peanuts Treasury

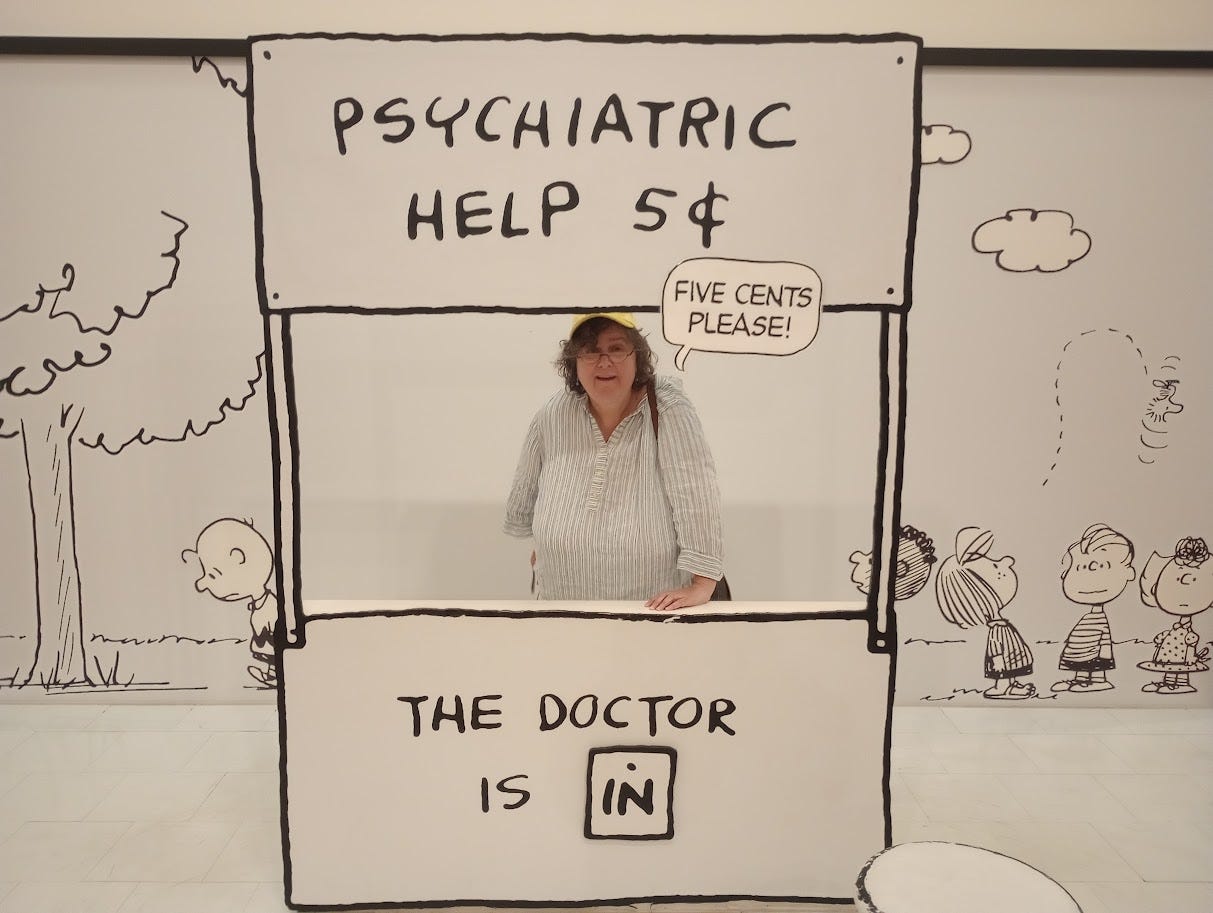

Instagrammable photo ops abound throughout the Charles M. Schulz Museum property. That should not be a surprise. Nor should it be a surprise that the building features Schulz cartoons everywhere, even in the loo:

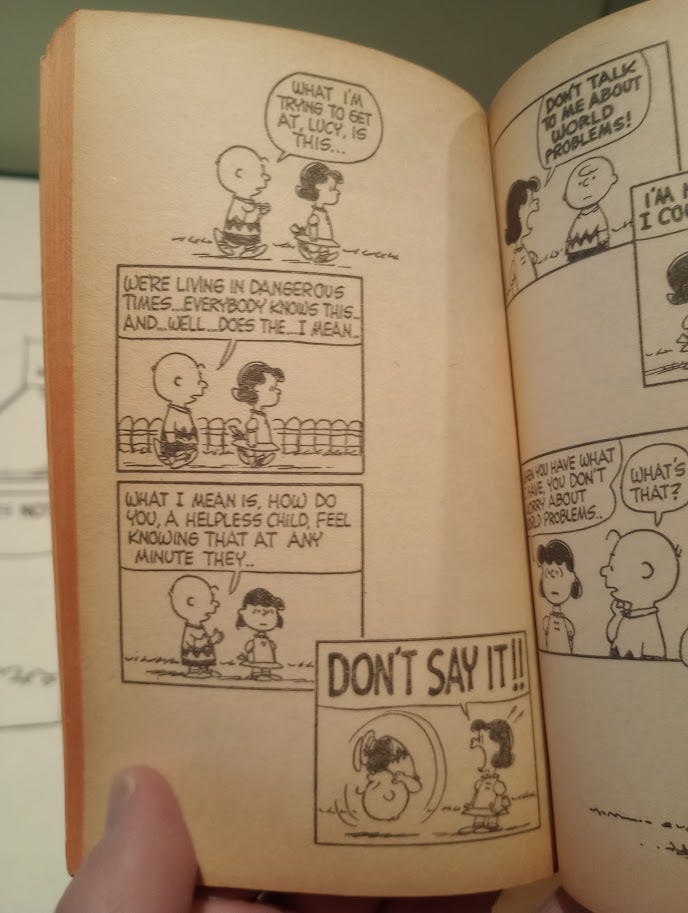

But there were surprises, and the first for me was laughing as much as I did. In my younger years, I had never noticed how sly and clever was the humor of Peanuts. It wasn’t all, say, repeated references to Lucy pulling the football away as Charlie tried to kick it, or Snoopy bizarrely pretending to be a World War I flying ace.

Schulz commented topically, mostly on American culture and society, without appearing to do so. The humor is timeless enough to speak to me decades later, in a very different social, cultural, and political context. What the cartoons meant to me forty or more years ago aren’t what they mean now. And the same is true for everyone. That’s what gives the Charles M. Schulz Museum relevance, even to young people who never knew Peanuts before they walk in the door.

Hoosen and I walked in fully expecting to be of the typical visitor age. We hadn’t accounted for school groups. And even if we don’t count those, we were still amazed by the wide diversity of ages among visitors that day. I can only imagine how differently we all saw the exhibits.

Museums, like books, are never a one-way messaging system from museum to visitor: They talk, you listen, is not how it works. Museums, no matter how good or bad, stimulate, provoke, and host interactions with visitors. And visitors never arrive as blank slates or, if you prefer, as vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge.

Museum visitors typically read or hear only what they want to, and then absorb it selectively, ignoring what they don’t understand or absorb or choose not to read to begin with, and putting what they do consider into the context of their own lives, knowledge, and biases.

Most visitors to the Schulz Museum are, I suspect, either adults nostalgic for Peanuts, or kids (from pre-school to teen) who have little or no familiarity with the strip, and certainly no recollection of the period in which it was created. The Museum does not at any point say, hey, folks, Peanuts and Charles M. Schulz himself were products of the early to mid- 20th century.

Being an old-fashioned sort of historian, one who has waded through thousands of handwritten 18th century letters, who believes no pain, no gain, I tend to look down my nose at popcorn-breathed professors whose work involves watching TV or movies and then “analyzing” what they saw.

So I thought it was going to be easy writing about the Charles M. Schulz Museum, that it would make a nicely lightweight “Hoosen’s Choice” post.

I was wrong. Or maybe, like Peanuts, what we see at the Schulz Museum depends not only on who’s thinking about it, but also on what else is going on when they visit. As the Museum observed, “Charles M. Schulz had a talent for creating timeless themes that were also great fun.”

So the thing about museums that serve as shrines to one person, whose own funds paid for it, is that we shouldn’t expect too much in the way of criticism of their subjects.

US Presidential Libraries/Museums are a striking example of such museums. That’s why I was pleasantly surprised by the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library’s hard-hitting temporary exhibit on FDR’s last term as US President, his ill-health, the cover-up, and FDR’s shocking failure to adequately prepare Harry S Truman, his vice-president, to take over from him in the midst of global war. I was also pleased to see the FDR museum deal honestly and openly with FDR’s decision to imprison Americans of Japanese descent, and showing the dissenting voices who tried to persuade him otherwise. Oh, and even FDR’s girlfriends got mentions. Big hand to the FDR Presidential Library, because this isn’t typical of the genre.

The Charles M. Schulz Museum is more like a typical presidential library museum. Any dirt on Charles M. Schulz isn’t on display in the Charles M. Schulz Museum. I didn’t know anything about this man, so I was ill-prepared to interpret his story.

This was also a museum that was in many ways ahistorical, despite an entire floor being dedicated to Charles Schulz’s life.

Everything I say from here on out should be read in these contexts, and in the context of the recent day on which I visited, which was among not the happiest of days, let’s put it that way.

Here’s To You, Charlie Brown

The first floor of the Schulz Museum isn’t primarily focused on Charles M. Schulz himself, but on his art and writing, especially Peanuts, and on advocating the joys of reading for us all.

I remembered wondering, long ago, why Schulz’s strip had that odd ill-fitting name, Peanuts, and I couldn’t make head or tail of it. No wonder: I now learned that the name was foisted on Schulz’s cartoon by an editor, apparently at random.

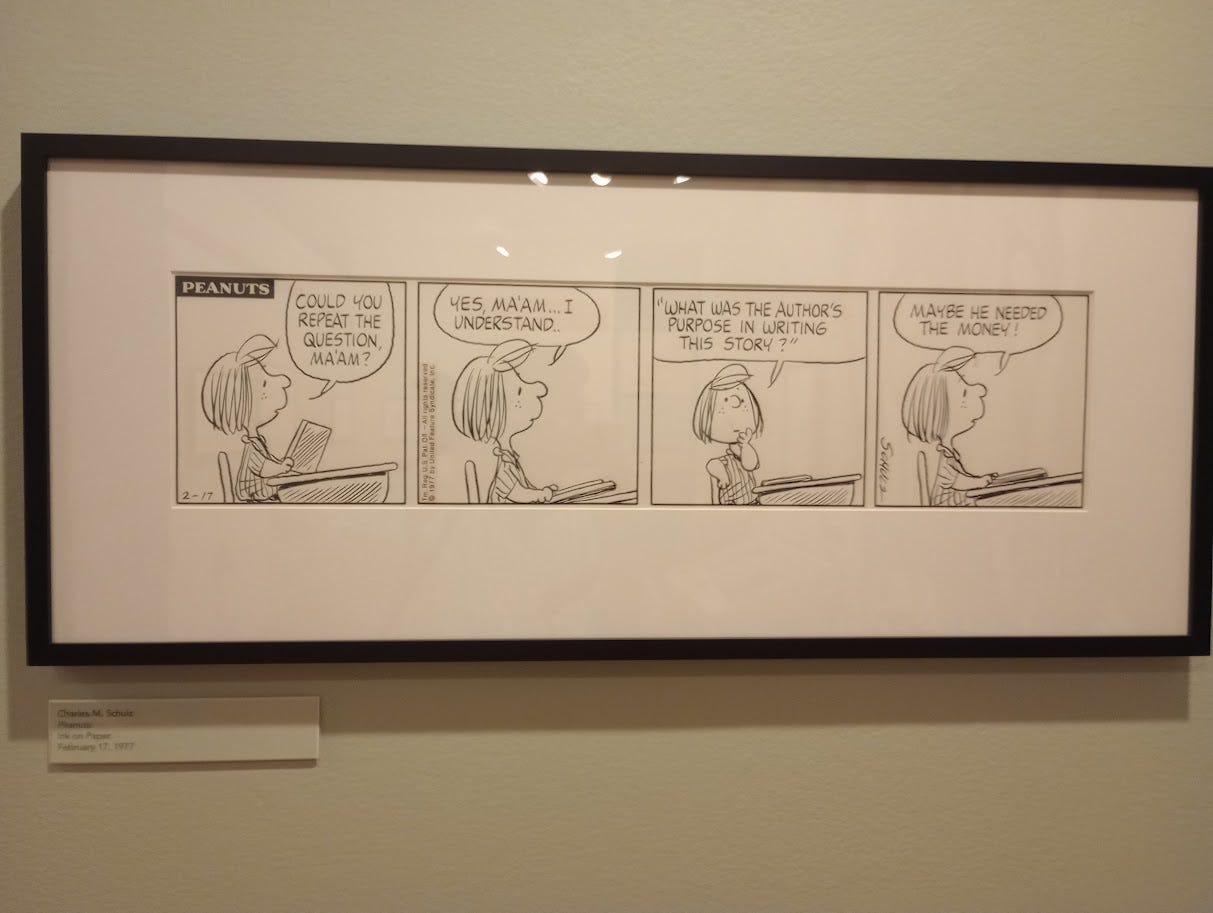

I can deliver little nuggety gems of trivia like that, but I cannot assume which of the many Peanuts strips on the Museum walls and in the books on display might speak to you, or how. So I will just include some of my favorites, the ones that made me laugh out and made me think.

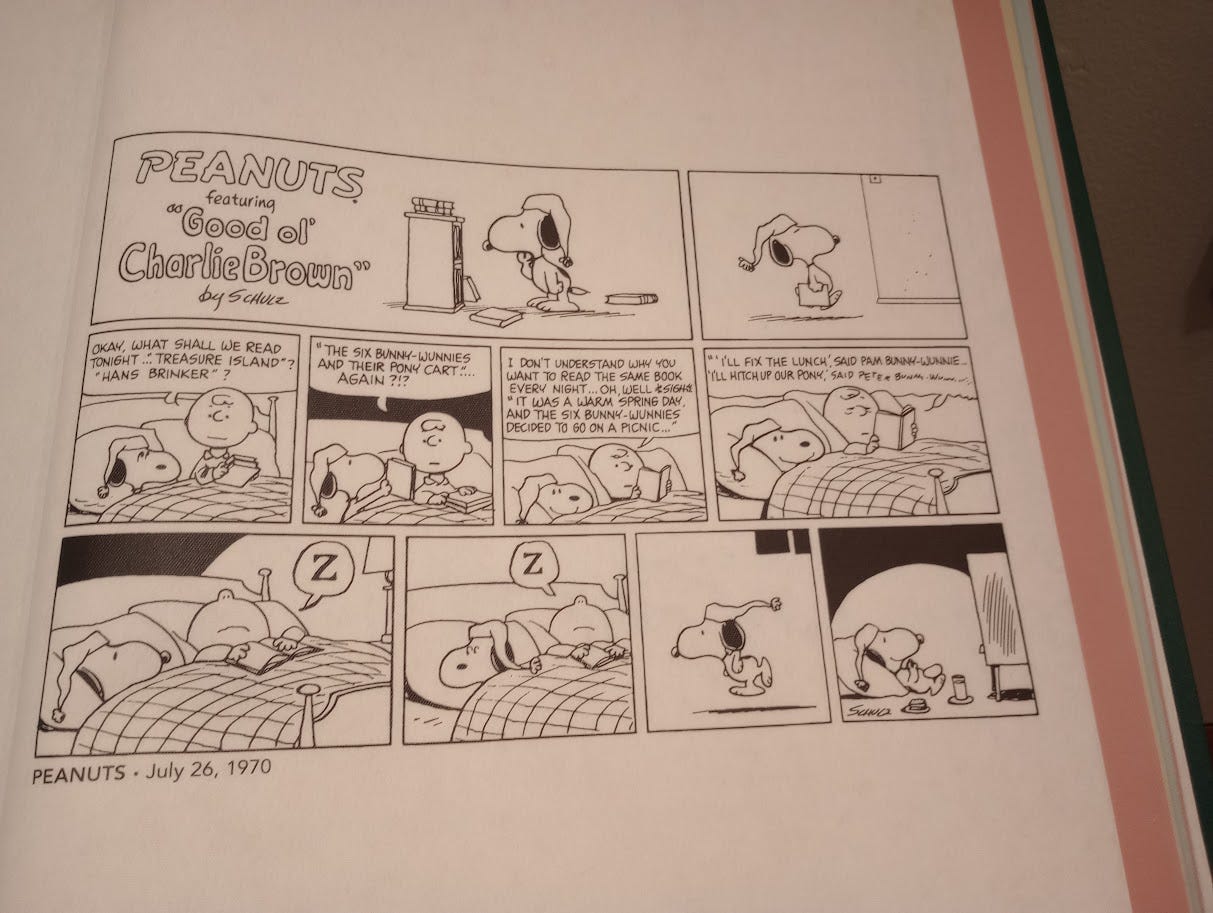

Let me show you this first cartoon, and then give my take on it. This might need to be read on a device larger than a smartphone:

Why did this strip appeal to me? I’m a keen reader but, like most of my generation, and perhaps especially in the UK, I grew up in a house where the TV was almost always on. Far be it from me to diss television: 1970s British TV was hugely educational, even when it was trashy, like Doctor Who, and it got me reading history and literature for myself.

And so sometimes, I’m just in the mood for the telly. Like many people, I got through COVID watching The Golden Girls. Right now, I’m finding reading heavy history unusually tough going. So in the evenings, I’m watching Agatha Raisin, a silly detective series.

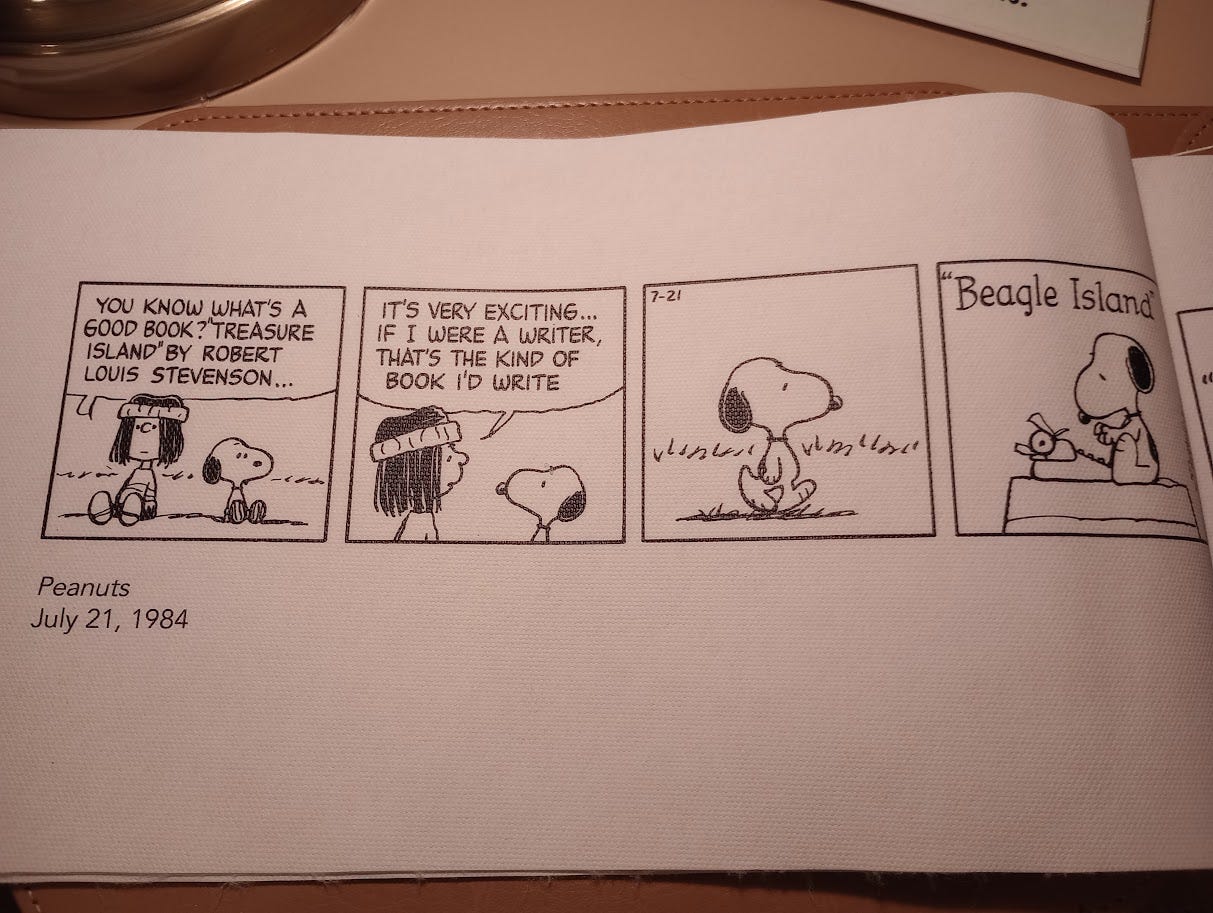

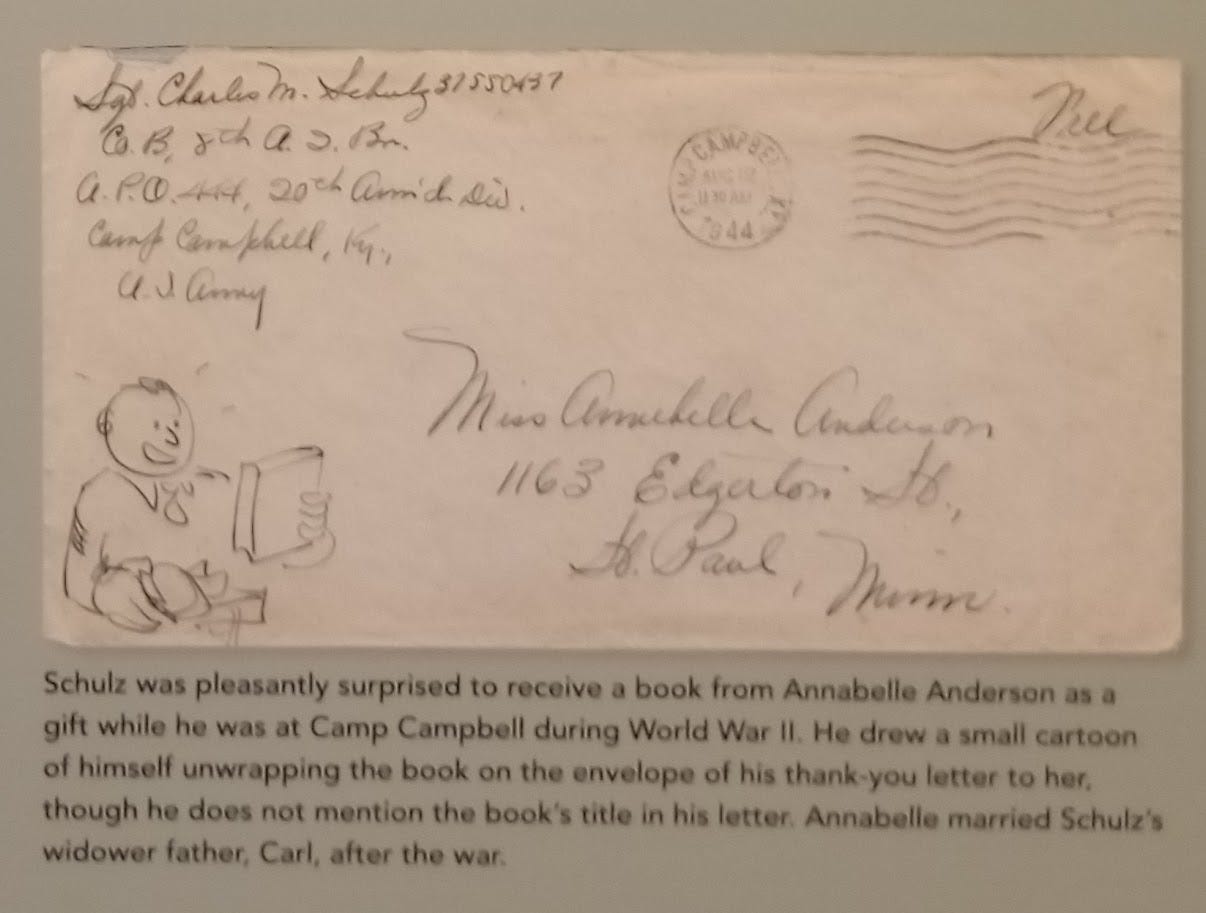

This next Peanuts strip shows the limits of creativity. One reason I turned to writing novels, fiction, after I quit my academic job was that it was a nice break not to be shackled to facts and evidence (even though, perhaps inevitably, I took great care with the history in my books). To write Non-Boring History, creative non-fiction, I depend heavily on the work of my learned colleagues in academic and public history, and, unlike Artificial “Intelligence”, I give them full credit. I'm dedicated to adding my own creative take in interpreting their work, which is one reason I write so personally. Here’s Snoopy as author:

The next three strips share a theme, that of parasocial relationships, an expression unknown in Charles Schulz's lifetime. One reason I love to meet with my paying readers for coffee whenever possible (and that’s quite the challenge, given my wide-ranging readers and chaotic travel plans) is to at least try to go beyond an entirely parasocial relationship.

Parasocial relationships are most typically thought of as the relationships between celebs and their fans. But it has come to bother me how more and more human relationships are at least partly parasocial, as so many people prefer to communicate in texts and posts rather than in personal meetings, even with close friends and family.

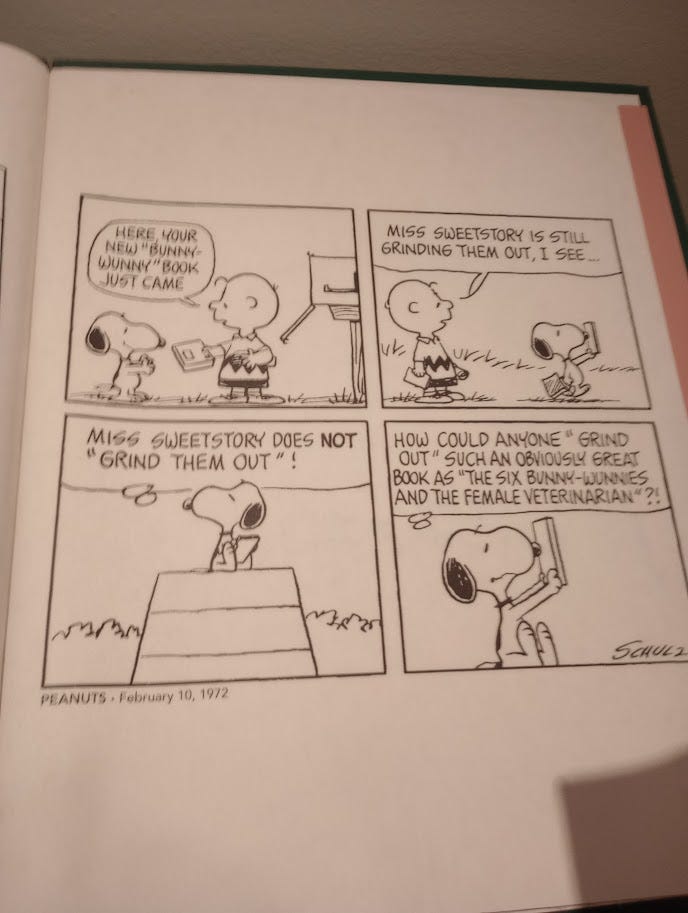

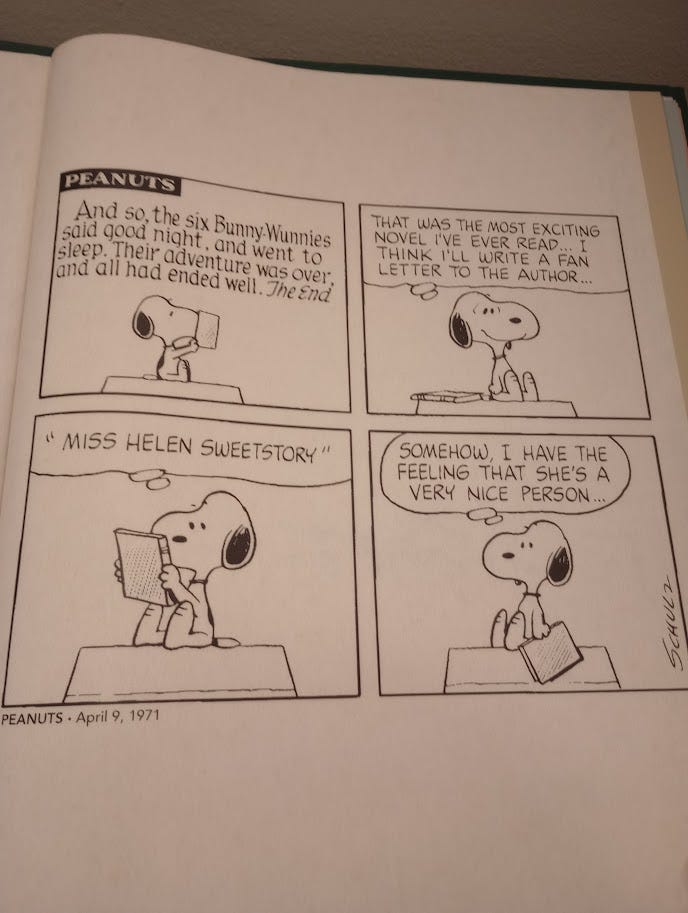

Here are three of the Peanuts strips about the parasocial relationship between Snoopy and his idol, a sickly sweet Southern author named Miss Helen Sweetstory, author of the fictitious Bunny-Wunny series.

And finally, the brutal truth about author Miss Helen Sweetstory’s parasocial relationship with Snoopy:

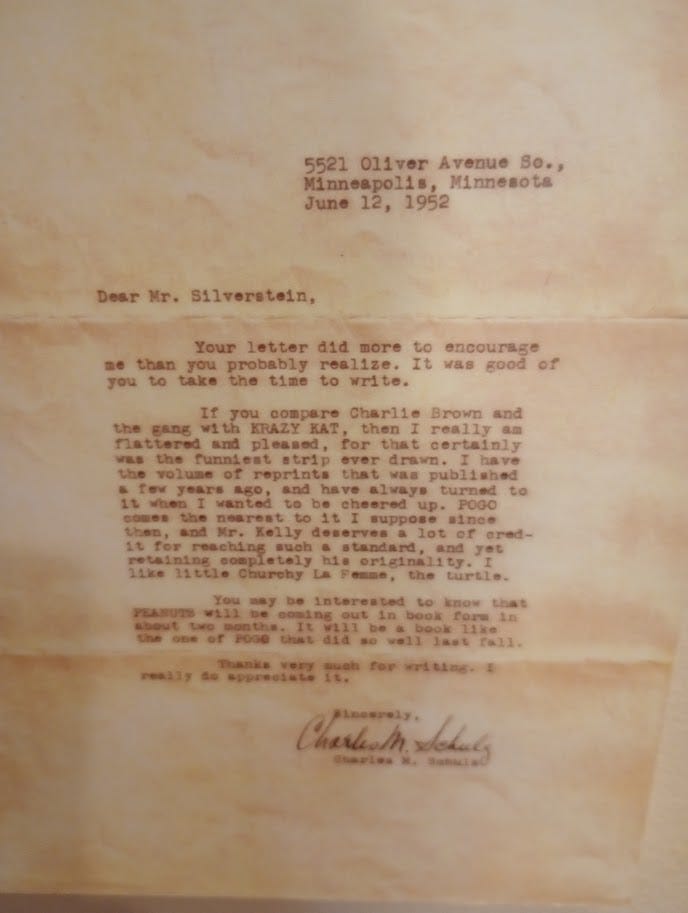

Note Schulz’s own intriguingly cynical take on parasocial relationships. It's especially interesting now I know he was a champ at responding to fan mail.

Charles Schultz understood the challenges of fan mail, since he received sacks of it every day. Every author loves fan mail, but sacks of it? Yikes. I did a browse on the internet, and there’s evidence that Schulz replied personally to a lot of people, and often included a little drawing in his replies.

This is stunning. I honestly don't understand how it would be possible. I try to respond to every comment, every email, and I do so without form letters or (God forbid) AI, or artificial intelligence. But (let’s be honest) I don’t exactly get the same volume of fan mail as Schulz did. That makes it possible to return the love, to offer to send my paid subscribers occasional postcards or other snail-mail correspondence (all they have to do is send me an address), and I enjoy doing so. Yet I feel like a failed human being compared to Schulz, a writer who would take on the gargantuan task of answering so much mail (but how? niggles a voice in my head). Who was this man?

You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown

Walking into the Museum, I knew almost nothing of Charles M. Schulz, not even what he looked like. I didn’t even know his nickname was “Sparky”, which came from—no kidding— a cartoon character. But I did have warm if vague memories of Snoopy, Charlie Brown, and the gang, because who of my age does not?

Just as I have a soft spot for FDR that I furiously interrogate at every turn, I have a soft spot for Peanuts . . . but I wasn’t sure I wanted to interrogate its author at all. However, to the second floor I went. Here were displays on Schulz the artist (which didn’t interest me, no artist am I) and Schulz the man.

On the second floor, I learned that Charles M. Schulz was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1922, and was a WWII veteran.

Ah.

WWII veteran . . .

I knew then that my critical thinking skills were in serious danger of going right out the window. And that matters, because let’s just say I wasn’t in the greatest frame of mind the day I walked into Charles Schulz’s world. I was vulnerable to being charmed, to enticing stories of goodness, to nostalgia for the Seventies, for the WWII generation, to wanting to believe firmly in a time when good and evil were clearly defined for all. That was the baggage I took upstairs with me.

You have been warned.

I’m hardly alone, of course, in my awe for the WWII generation, I know that. Members of it were my grandparents, my most influential teachers, my most respected role models. These were people who were not bland, not unctuously “nice”, and often very difficult. They were imperfect. But those I knew well had integrity, and many I would have unquestioningly trusted with my life. Some, this rebellious contrarian in training would have followed to the end of the earth.

As evidence, I give you the breakout star of my first novel, Don’t Know Where, Don’t Know When, a fierce fiftysomething British WWII woman I named Elizabeth Devenish, and whom I inadvertently modeled on an old teacher in England I had held in awe. She was so popular with my readers of all ages, I brought her back in the last novel of the series, this time as a complicated and difficult teenager in 1905, struggling to find a moral view of the world in the absence of a vanished father.

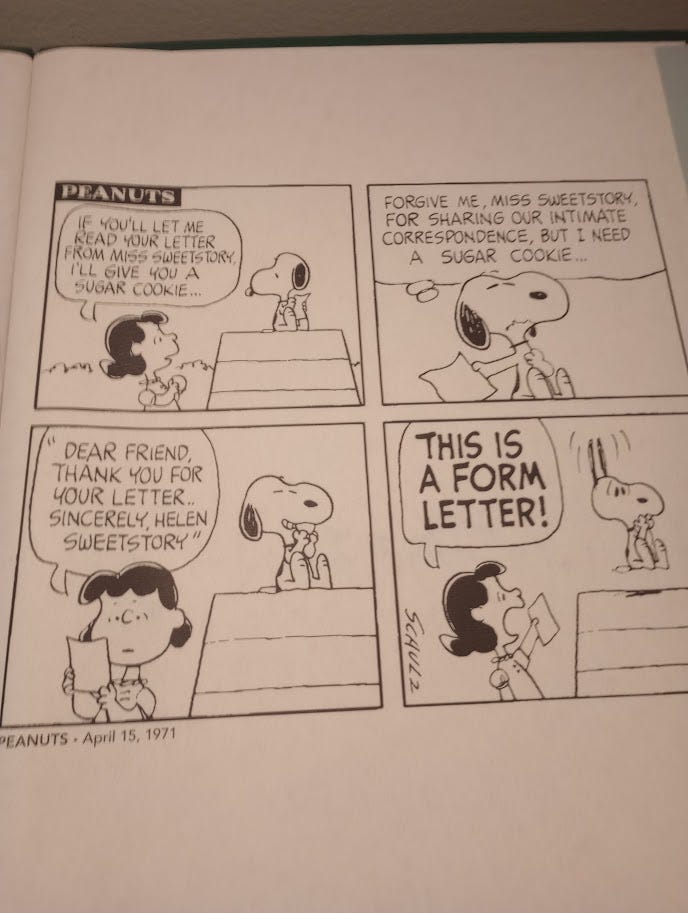

Charles Schulz would not have approved of my having outed my muse for Elizabeth Devenish, having said he regarded it as a rotten thing to do to people, to model a character on them. I’m not sure he’s wrong.

But he didn’t know my old teacher. She would never say it out loud to me, but I had it on excellent authority that she was thrilled when I flew to London to see her after 25 years, and told her she had emerged out of my subconscious and into my novel. Yet, and this is a story for another time, my connection with her really wasn’t that simple, and it turned out to be more parasocial than I had wished. How well do we know anyone to whom we're not on equal footing, who is from a different generation, no matter how hard we try?

Anyway, I didn't know Charles Schulz. I’m not sure I believe him that he didn’t model characters on real people. Check this out:

I know what it means to write fiction, that it’s never entirely about other people. No matter how much we try to see our characters as not ourselves, perhaps thinking of people on whom we hope to base those characters, we never quite succeed. Quite a bit of an author sneaks into every single character she creates. I always assumed the kind but anxious and insecure Charlie Brown was at least in part Charles M. Schulz’s alter ego, and I still do. In Schulz’s words in the Museum,

"Anyone who creates a comic strip and is doing it day after day works in the same manner as a novelist does. If you're going to survive on a daily comic strip, you must draw upon every experience and thought you've ever had. That is, if you are going to do anything with any meaning. It would be impossible in this kind of strip to create any character and not be part of it yourself."

By the time I reached the second floor of the Museum, I reckoned that Schulz's work and quotes posted on the walls of the first floor had already shown me the man. The second floor was just a chance to learn some background, some structure, for his life.

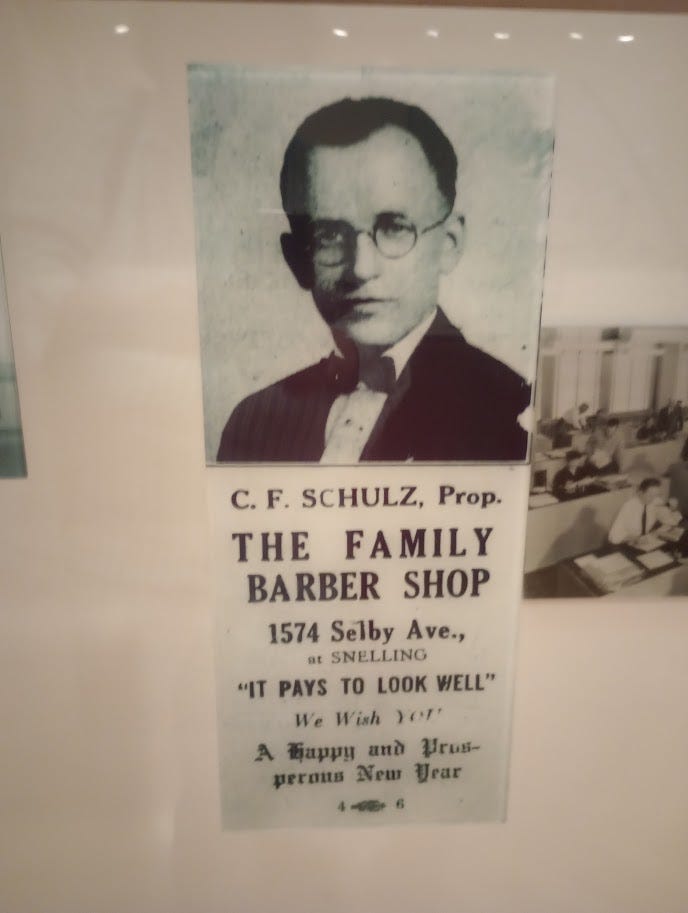

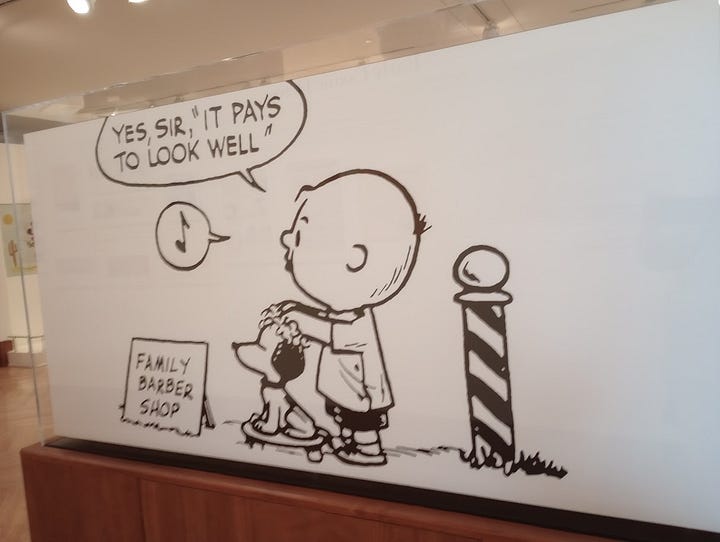

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1922, Charles Schulz was the son of working-class/lower middle-class parents. His father was a barber, and you bet the family business pops up in Peanuts:

Neither of Schulz’s parents had much formal education, which was absolutely typical of the times, and neither, again typical, had much informal education, gained through reading. Neither of them read books. According to museum text, Schulz observed that his mother was not confident she could understand anything more complex than Reader's Digest.

Yet, unlike his parents, and far too many credentialed yet poorly educated people today, Schulz was a reader. I want to emphasize that side of him, as the Museum does, from the start, on the first floor(UK ground floor):

"I find it difficult to go home without stopping in at the bookstore at night. Like an alcoholic who has to stop at the bar for a drink, I have to buy a book before I go home. I keep storing books up, thinking that even if I don't read them now, at least I have them to read. I hate the thought that I might be trapped at home without something I want to read. And yet, it's a never-ending process. You can't read everything. The more you read, the more you discover there is to read."

—Charles M. Schulz

Love of reading, encouragement of reading, is a huge part of the Museum’s message. There’s never been a more timely message, and it comes from Charles Schulz’s lifelong passion for reading for pleasure.

That’s reflected in the design of the museum, and especially on the first floor, where three-dimensional artifacts are secondary to the cartoons all around us on the walls and in books we’re invited to read. Comfy sofas with coffee tables loaded with Schulz’s books beckon us to settle in. An official Reading Nook, open to all, but aimed at families, offers cozy, snuggly spaces for reading aloud, and a collection of Schulz’s books kindly donated by fans awaits our choices in several cases. When I popped my head around the door of the Nook, a dad was reading to his two small kids. Kids love being read to: Physical closeness associates reading with love.

Asked how come he was a reader, Charles Schulz said he didn’t know. Please note: He certainly didn’t like the books he was handed in school.

Charles Schulz certainly hit on one historical reason for his reading enthusiasm: The widespread availability of portable cheap paperbacks in the 20th century, and especially during WWII, when his love a reading blossomed. Little books that could be stashed in a pocket were distributed free of charge among American troops.

This reference to cheap, portable books rang bells that whisked me back, bizarrely, to rural Kansas. It seems that cheap paperbacks did not originate with Penguin in London, as I had long been told, or with a German press which also took credit, but with a radical American press in a small Kansas town, a town that Hoosen and I stumbled upon in our random travels:

I strongly believe that a GOOD (underline that “GOOD”) formal education helps to discipline crazy thinking, to compel us to think critically in a way that's moored to respect for evidence, all of it, not just the evidence we like. But, at the end of the day, it’s up to us to educate ourselves, to read, and to read widely, not just stuff we are forced to read, or books that flatter us that we’re right about everything, or are fast food for the brain. Charles Schulz took full advantage of those cheap paperbacks.

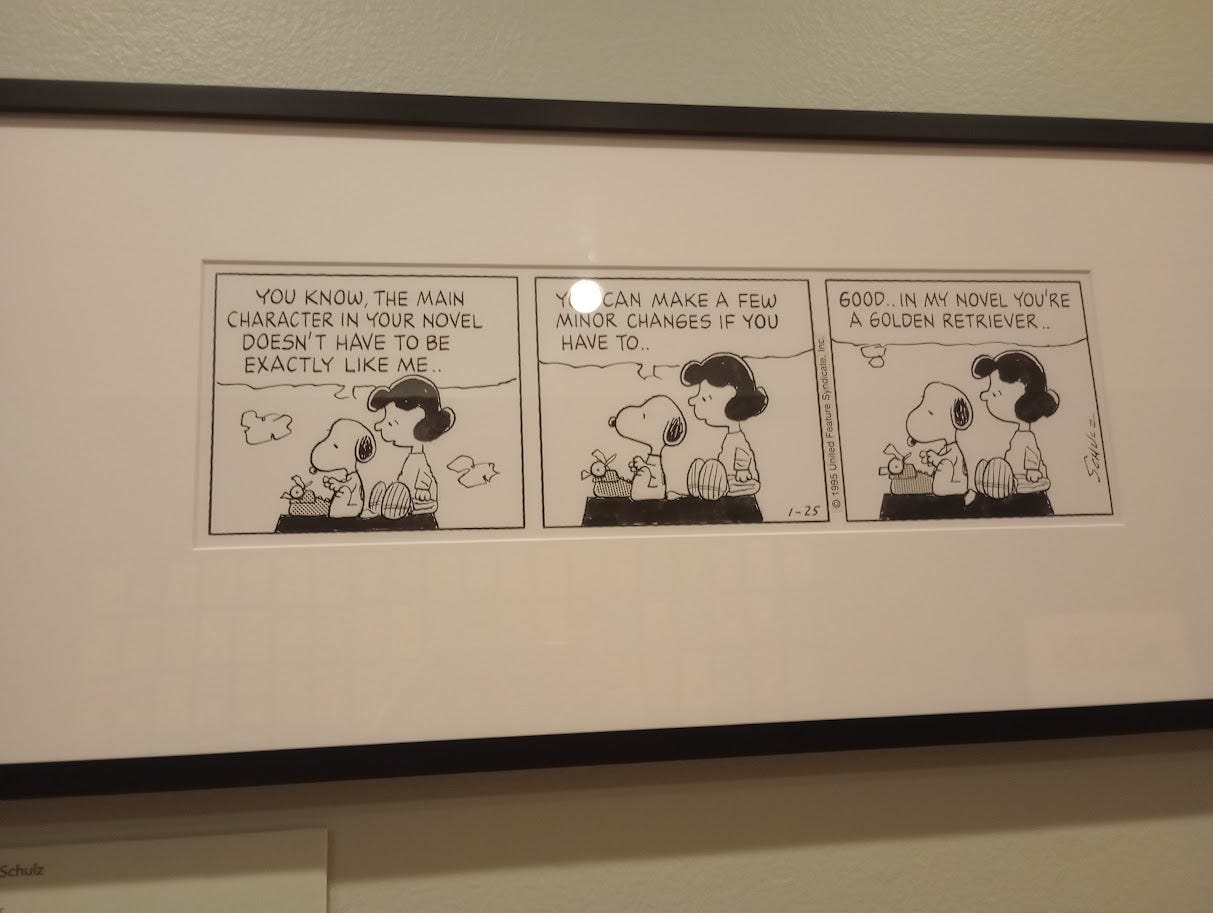

Schulz also got at least one book as a gift, from his future stepmother. This envelope contained his thank-you note, mailed to her in St. Paul, Minnesota, from Camp Campbell, Kentucky. The sketch is of his delight at opening the package containing her present:

Even a personal letter or gift is a form of fan mail. Schulz’s replies to fan mail are everywhere, cherished possessions scattered around America, in attics and the globe, on walls, in the hands of fans, and their adult children and grandchildren, treasured mementos of a parasocial relationship that people first developed with Charles Schulz through Peanuts strips:

Being a writer is lonely, and leaves us vulnerable to feeling isolated and our work unappreciated, no matter the reassurances of our nearest and dearest. Fan mail really matters, and helps soothe the soul.

Be Kind, Be Brave, Be You

Bill Watterson, a fellow cartoonist (Calvin and Hobbes) of a later generation, said it best about what Peanuts signified:

"Peanuts pretty much defines the modern comic strip, so even now it's hard to see it with fresh eyes. The clean, minimalist drawings, the sarcastic humor, the unflinching emotional honesty, the inner thoughts of a household pet, the serious treatment of children, the wild fantasies, the merchandising on an enormous scale – in countless ways, Schulz blazed the wide trail that most every cartoonist since has tried to follow.”

I have only one quibble with Watterson’s observation. I am a reader, not a cartoonist, and I do think it’s possible to see Peanuts with fresh eyes. All of us can. Schulz is remembered for being topical for a cartoonist, which could easily have dated him. But he was wily in avoiding most specific references to current events and so, somehow, his work still seems fresh, even in vastly different times.

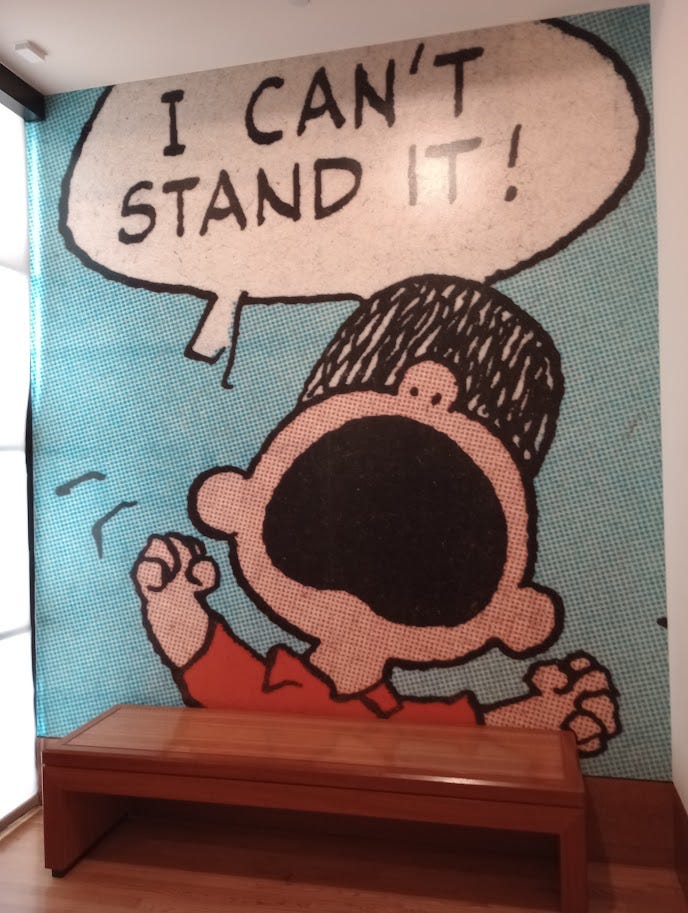

This next image, I am sorry to say, sums up my mood during much of our Western trip, loaded down with baggage of events that I cannot control, and in which I feel like a hillful of beans, with apologies to Casablanca.

Logically, I knew I was not alone, thanks to the ever-loyal and lovely Hoosen, my long-suffering spouse, and the ever-loving Hoosen, Jr. Yet I still felt alone, and afraid. I looked resentfully at strangers enjoying themselves. How are you living your lives normally, I wondered? How is that possible? Sometimes, I'm just like . . .

When I saw this mural in the Schulz Museum, I no longer felt alone. Why I felt this way had nothing to do with whatever Charles Schulz had in mind when he drew it. But clearly, the Museum curators predicted that when they installed it, without label or context. Years ago, they chose this panel to be a big mural , and then left it open to visitors’ interpretation. I interpreted, silently, and with gratitude.

I’m torn. Torn between telling you how soothing that day was, and looking back on it through a more critical lens, struggling not to date my post, while knowing it’s the product of a particular person, time, and place. NBH is about history, but it is not history, so I seek to entertain, but none of us are here just for entertainment. Or only for historical facts. We're also here for a relationship that's parasocial, and yet, reader, let me tell you, I'm more myself in my written words than in any other way. I'm sure the same was true of Charles Schulz.

Happiness Is A Warm Puppy

We probably wouldn’t have visited the ice rink next door to the Charles M. Schulz Museum had it not been for its cafe. We needed lunch.

The ice rink was built by Charles M. Schulz, a keen ice skater, just like his character Charlie Brown, who appears outside as a statue in ice hockey gear. This is one of the few ice rinks in Northern California. Rather than reserve the skating rink for the use of himself and rich friends, Schulz, the WWII guy, built it as a gift to the town.

The Warm Puppy Cafe serves breakfast, lunch, and snacks, and it’s nothing fancy. Charles Schulz ate here every day while in town, for breakfast, and lunch. One table was set aside for his exclusive use. Sometimes, he was joined by friends, but often, he sat alone, quietly people-watching. His regular lunch order was a tuna sandwich. I don’t know if that was a cold sandwich, or if it was the tuna melt (hot and made with cheese) on the menu now.

In tribute, Hoosen and I ordered the tuna melt, which came with fries, and split it, which turned out to be a good idea, given the portion size. It was truly the best tuna melt I’ve ever eaten. Maybe all that cheese helped. Loved the cups, too.

Through the cafe window, Hoosen and I watched the skaters as we ate. Some were seasoned veterans, like an older woman I’m still not convinced wasn’t Charles M. Schulz’s widow. Others were brave beginners, bent over and clinging to large plastic barrels as they gingerly shuffled on the ice. I was impressed: I never tried ice skating, never had the opportunity when I was young, and won’t start now. Hoosen skated a bit as a young ‘un, lucky him.

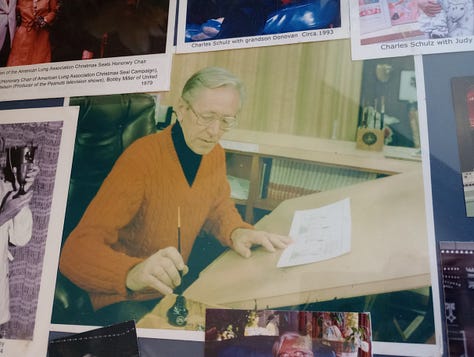

Looking back at the cafe, I glanced at the corner by the fireplace, to Charles Schulz’s table, still reserved exclusively for him, long after his death. There’s a vase of fresh flowers on top, and various photos and mementos under the glass, including photos of Schulz with President Jimmy Carter, and working on a strip at his own desk, which is now in the Museum.

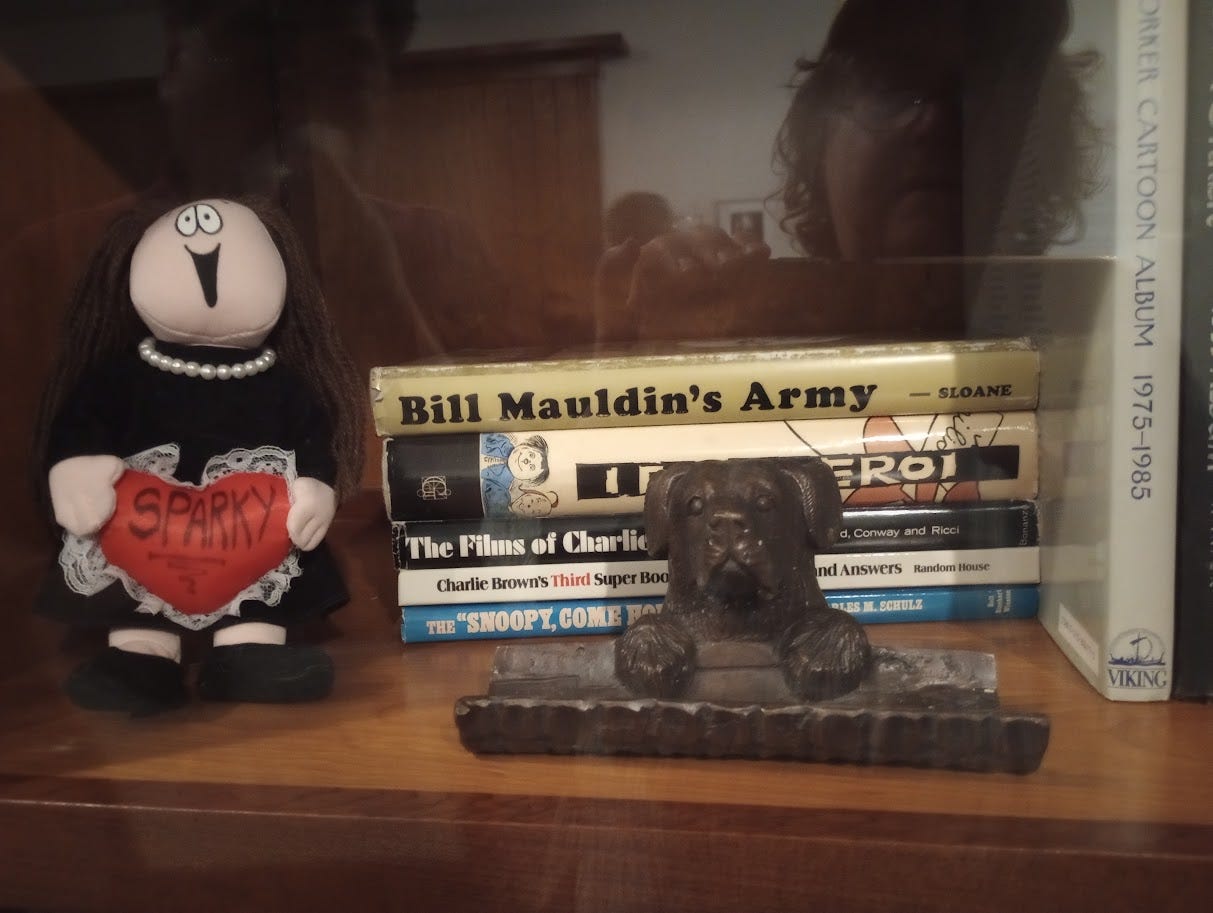

Now, from my table with Hoosen, I looked again at “Sparky’s” table, and held up my tuna sandwich. He smiled and nodded back. I know this sounds crazy, but he would have understood that I wasn’t crazy, just imaginative, so necessary to being creative. I felt a little closer toward him in that moment than I had in his recreated study in the museum, even though that space was filled with his books, mementoes, and little tokens of love from other comic artists, like Cathy Guisewite (creator of Cathy), who gave him the doll on left below:

STOP.

HOLD IT RIGHT THERE.

Good Grief, Charlie Brown

Time to touch base. To remind us all: I am a trained historian, and Non-Boring History is about history. I am a missionary, and I intend to spark your interest in my favorite subject, no matter your views or beliefs. I invite you to explore history through reading and travel, and to critically appreciate evidence-based history and the academic and public historians who write and interpret it.

But Non-Boring History is not itself history. I do not hold to the same standard as scholarly work, because it’s simply not possible, and not desirable when I need to hold your interest to reach you at all: Unlike my college students, you are not a captive audience.

There’s more. While I have a degree in journalism, and I trained to write news stories and op ed pieces, Non-Boring History isn’t news reporting, either, and, while I often insert my take in my posts, I avoid politics and punditry like the plague, and almost never do I write op-ed pieces here.

My historian side and my journalist side both weigh in at NBH, but they aren’t perfect, either. I think of a long-gone historian who dedicated his life to the biography of one great man, and who ended up imitating his views, manners, even appearance. Objectivity in pursuit of truth should always be a goal: Don’t trust historians who tell you only what you are already inclined to think, particularly about current events, and who never tell you that all historians do NOT think alike. At the heart of being a historian is not certainty, but doubt, contingency, uncertainty, except in facts that are proven by overwhelming evidence. All else is interpretation, and interpretation should be in pursuit of objective truth (no matter how elusive), and with great humility.

But objectivity is only a goal, even at the best of times, and never an achievement. However, in pursuit of that goal, I now force myself to snap out of my happy feelings of well-being from that delightful and soothing day at the Charles M. Schulz Museum. Happiness is a Warm Puppy, that’s the original saying by Schulz, so the Warm Puppy Cafe was happiness, including for me.

Like virtually all visitors to the Museum, I didn’t know Charles Schulz. Never met him. Never even read a biography. And I spent a couple of hours or so immersed in an establishment dedicated to preserving not only his work, but a relentlessly positive image of him as a person. We live in an age of highly sophisticated propaganda, and it affects us all.

I don't know this guy, I think again. Now I recall noticing, on the museum’s second floor, the timeline about Charles Schulz’s life. It was mostly a story of humble childhood, WWII military service, fame and fortune, awards and recognition. But I did notice that, in the early seventies, Charles Schulz married his much younger second wife a year after divorcing the first.

I looked this up on my phone, and learned that there was another much younger girlfriend around the same time, in the very early Seventies, while he was still married to Wife #1. Schulz apparently referred to his affair in Peanuts. It’s worth looking at this link, on Tracey Claudius’s 2012 sale of her letters from Schulz, for the very revealing cartoons he sent his mistress. Don’t worry, they’re clean, just a bit . . . needy. Possibly creepy.

In my mind’s eye, I look again at the corner table by the window and fireplace at the Warm Puppy Cafe, and it’s empty. There’s not even a chair. That’s the cold, hard reality. My relationship with Charles Schulz is entirely parasocial. In the end, my relationship is not with him, but with Peanuts, and it is not his sole work. Every reader engages with a text creatively, and on our terms as well as the author’s.

Sir, Is This Love

Since the 1990s, we’ve been told to not judge people. The origin may seem to be old and Biblical, a reference to "Judge not, lest ye be judged" from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount. But it’s not, it’s new.

I remember being surrounded by judgment in my post-WWII British childhood, by people who had confronted grotesque evil during the War, and who thought in moral absolutes, and whom I would not have dreamed of telling “don’t be judgmental.”

I first met this new anti-judgment creed in 1980s America. It did not strike me as Christian, or even religious, but it was bossily and relentlessly positive. “Don’t be judgmental!” people scolded me, with an unspoken “Or else!” A Jewish historian with whom I long ago loved to kvetch (grumble) put down that view of the world: “Hitler,” she joked grimly, “Pro or con?”

Other people scolding us to “not be judgmental” are telling us not only to be silent about what we think, but what to think about people and their dodgier actions.

Charles Schulz’s museum is dedicated to shaping his legacy as a writer and artist and WWII veteran, but also as a man. Here's where the historian and journo and person I am come together: I don't like being gaslit, being manipulated, much less threatened to force me to conform in my thoughts as well as statements. I don't like being told not to see things, not to know things, not to think things, and not to ask awkward questions. Alas, this is why historians aren’t invited to parties.

What I’m about to say may offend or trouble some of my readers. It is judgmental. I have reasons. It is not personal, if that helps. And I still have doubts. But.

I’m well aware that many marriages in America fell apart in the 1970s, and that Britain followed suit in the early 80s. Some dissolved for very good reasons, like utterly incompatible people who had married young under social pressure in the 1950s, or marriages featuring abuse of all kinds. But I also saw too much damage done to friends, too much anguish caused by philandering spouses who left behind partners, usually wives who had loved and supported, who were devastated emotionally, socially, financially, and in the most personal way.

And that's before we get to the kids whose worlds and sense of security were shattered by the departure of a (usually male, sorry) parent, and who were condemned to shuttle among “homes”, among broken parts of a family, and to pretend this was ok. Maybe this is why my central characters in my novels are young women struggling with abandonment by parents.

I’ve seen too much happen around me. I'm tired of picking up the emotional pieces into which good kind friends were shattered when partners decided that relationships weren’t fun anymore. I think of when the other party waltzed into the sunset with not a care, having lied to everyone about the real reason for the split, and those lies being unquestioningly accepted by acquaintances and admirers, by parasocial friends.

As someone with a tendency to hero-worship, it's just as well for my critical thinking skills that I trained as a historian, forcing me always to play devil's advocate. In the end, thinking about it, I realized that I wasn't interested in knowing Charles Schulz. Peanuts is all I need or want to know: The snarky undercurrents (not a bad thing, mind), the odd characters, the timeless commentary on an imperfect world, created by an imperfect and—to us strangers—unknowable man:

The strip above made me think of the people who make serious money from writing these days. Almost all are celebrities. Even President Jimmy Carter knocked out children’s books, everyone famous does, because sales of books by famous people are guaranteed, even though quality is not. At least one very famous British celeb started a newsletter, collected money from subscribers, and then abandoned his newsletter. But people want to know the famous, and forgiveness for them is infinite,so I see nobody complaining.

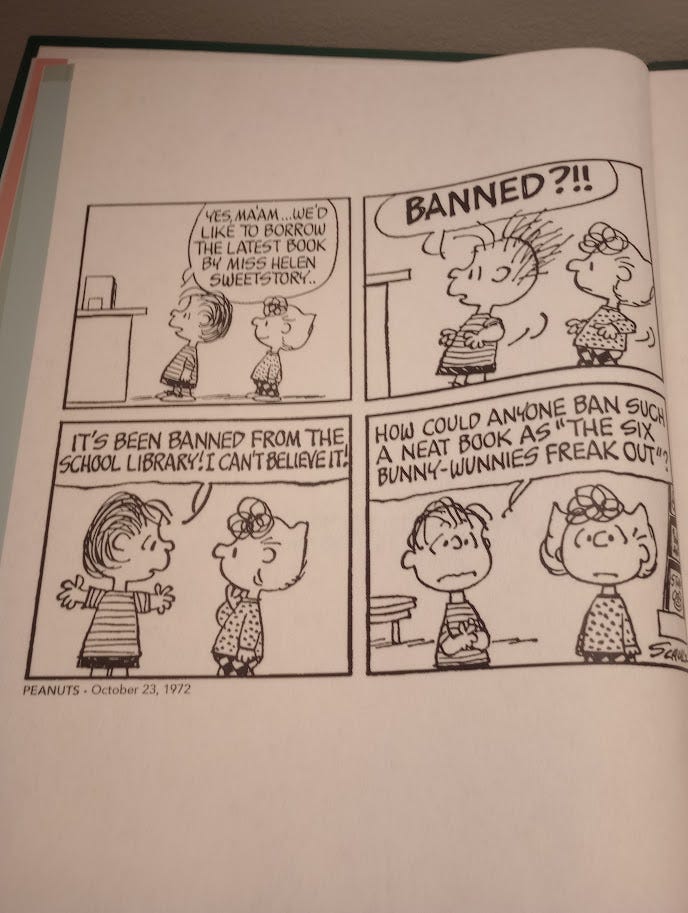

This next strip introduces a bit of nuance from 1972. I think now of the recent kerfuffle over school librarians “banning” books, which fails to note that these books are available in public libraries and bookstores, and so are not actually banned. School librarians must curate, must make decisions about which books to stock in their schools, especially when money and space are tight, and community standards are conservative. Stephen King's horror book, just one example, are not available in elementary school libraries, so far as I know. I love that Schulz understood in 1972 that librarians’ decisions are not uncomplicated decisions:

And here’s that sly humor again. Snoopy, capable of reading heavyweight novels, had fallen in love with the drivel knocked out by Helen Sweetstory, drawn in by their parasocial relationship, which was shattered when Snoopy figured out that he hadn’t known her at all:

One thing I always tell Nonnies (paying subscribers) when we meet is that I’m afraid of disappointing you when you actually meet me. Our parasocial relationship isn’t all one way. That my most supportive fans, those who actually care that I need money to do what I do, sense a connection that is more real than we understand. And it’s best done through words.

Charles Schulz gets it, even long after his death. I know, through his words:

I didn’t expect much from the Charles M. Schulz Museum, which is why I had put off visiting it. I didn’t expect or, in my heart, want dirt about Schulz, and in that, I wasn’t disappointed. This wasn’t an objective museum. And it wasn’t a history museum: While it showed the trajectory and major events and influences in Charles Schulz’s life, it did not provide much in the way of explanation of the larger historical context of his times. I would have preferred this museum be presented flat-out as an art museum, rather than as a shrine, to allow visitors to make up our own minds, to fall in love with the words and images, without the pressure to form a parasocial relationship with Charles Schulz, the man.

Yet history, in the form of thinking historically, proved inescapable for me. Despite my skepticism, and despite my normal dedication to writing critically about public history, this was one of these times when a post is more about me, you, us, than about its subject. I was moved by the first floor, the shrine to Peanuts. The Schulz Museum was nostalgic escapism, but also a reminder that something I thought I had left behind in the 80s was not as dusty as I had thought. Perhaps the flashy museum appearance helped, but what I saw in Schulz’s words spoke to me more clearly than ever before. That, I definitely did not expect.

I would like to thank the late Charles Schulz for reminding me of the therapeutic value of writing, not only for the writer, but for the reader. Truly, reading is treasured therapy that is cheap at the price, sometimes as little as five cents, or even free. We don’t have to be sickly sweet like Miss Helen Sweetstory (God forbid). Even the most rigorous and challenging academic history books often touch this historian with a deft turn of phrase, a lively character sketch, or an unexpected observation.

We should all be readers, as the museum urges and inspires us to be. We should all strive, as English novelist E.M Forster put it, to “Only Connect.” And, I would add, we should connect through reading, not only with others, but with ourselves.

Please support NBH as an annual or, if you prefer, monthly subscriber.

I LOVED every single Agatha Raisin story when I read them between 2010 and 2015, but then they made the series out of it and I hated it. My Aggie was nothing like Ashley Jensen's. Eye roll.

Anyway, from some piece I heard ages ago on NPR, I recall that Lucy based on Shultz's first wife whom he hated, and who apparently either couldn't cope with or contributed to, or both, Shultz's depression that set upon him when he returned from the war. I remember in that piece, too, thinking that his love letters to his paramour were a bit icky.

His quote about reading made me all misty. It's so dusty in here... 😉 I'd love to see that museum someday. I've always had a warm (puppy) spot in my heart for Peanuts.