Awkward Encounters with Lewis and Clark

ANNETTE ON THE ROAD Running into famous explorers at roadside restrooms. PLUS meet NBH SuperNonnie Caroline Ross!

Lewis and Clark Can Get Lost

Lewis and Clark? My non-US readers are now likely looking at me mystified. BUT my US readers are settling down for a lovely session of “Hey, I know about this! I learned about them in high school!”

“Learned”? Well, they were mentioned briefly, like everything else in the dreadful US survey classes that are inflicted again and again on young Americans, from third grade to college, like some hideous historical Groundhog Day.

So here’s how I imagine you probably recall L&C (as I shall call them), unless you’re a total L&C buff. . . .

Oh, wait. You're asking what I know about these two textbook stars?

{Cough} I meeeean . . . Technically, my PhD stretched to 1820. . . But honestly, I lose interest after the British leave.

Just kidding! Maybe. But . . Oh, for heavens sake. No, having a PhD in American history doesn't mean drilling down on everything in crappy textbooks until I master trivia like what color socks L&C wore. Not how academic history works. 🙄

Anyhow. Most people’s recollection of Lewis and Clark likely is something like this, okay, maybe less detailed than this, but hey:

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson bought a large part of what’s now the western United States from France, in what’s called the Louisiana Purchase. It should probably be called the Louisiana Supersale Bargain Blowout of the Century. Hey, Napoleon even threw in an ABSOLUTELY FREE set of steak knives!*

*Of course, the deal was actually a scam. France may have claimed it owned the big chunk of land it was selling, but the land actually belonged to and was inhabited by many, many Indigenous peoples, who would eventually realize that they had been ripped off big time.

Now, President Jefferson decided he needed someone to go check out his exciting new acquisition, to see what, exactly, he had just Louisiana Purchased. He certainly wasn't about to go himself. So he created the wonderfully-titled Corps of Discovery, and appointed his personal secretary, and former neighbor in Virginia, the delightfully named Meriwether Lewis, to lead it. Lewis was apparently happy to get the chance to exchange humdrum office work (plus living depressed in a far corner of the White House by his own choice) for a Western adventure that could make him famous. To prepare, he signed up for a bunch of crash courses with scientists, in subjects ranging from astronomy to botany.

Lewis decided he needed a co-leader for his road trip. It was a no-brainer: He hired his close friend William Clark, his senior officer from his army days, who may also have been his lover.

Wait, what?

Oh, you didn't hear that from Mrs. Grabowski in high school? Neither did the lads in the Lewis and Clark fan club, who got the vapors when historian William Benemann made a persuasive case for L&C having been partners.

UPDATE: Forgot to mention: I learned about Benemann’s article from this excellent brief piece (written for the public) by a historian who explains on behalf of the rest of us why it’s important that historians be allowed to ask awkward questions, without being attacked for doing so.

Having read the article, I'm like “Ya think?” Seriously, the lads in the L&C fan club need to grow up and get a grip, like the blue-haired Southern lady who gave tours of Thomas Jefferson’s house back in the nineties, who clutched her pearls at the vereh idea that Mistah Jefferson could have had a sexual relationship with an enslaved woman. Which he did. And my students laughed at her, as they should have. Yes, I was at Monticello to witness this.

But I digress.

So: A fine upstanding American couple (seriously, ever hear Clark mentioned without Lewis?), their chests sticking out (and this part Americans do remember) were accompanied by Sacagawea, a young Shoshone woman, who was, in American memory, some random Indian gal who just dropped whatever unimportant Indian things she was doing, and set off with these guys to show them the way aalllll across America, serving as their Knowledgeable Native Guide (not what happened, and I'll be tackling this soon).

I should mention that L&C, while absolutely worthy of being singled out for their skilled hard work, were not the only guys on the trip. A bunch of other blokes came too, including an enslaved man called York, owned by Clark, and Mr. Sacagawea. Of course there were others! Otherwise, we might remember the Corps of Discovery as the Three People and a Baby of Discovery.

Between 1804 and 1806, Lewis and Clark (and Sacagawea) (and her baby) (and the other lads) traveled all the way from Washington DC to what’s now Washington State, and back, while L&C took measurements, wrote up reports, checked out possible money-making opportunities for Americans, cooking (oh, that was Sacagawea) and snapping selfies.

Yes, of course there's a ton more to know about L&C, most of which I don't know— like almost every other historian! And for a long time, I was absolutely ok with that. I have plenty to read and think about, trust me. I don’t have to care deeply about everything. Honestly, I can’t. If you really want to know why, pop into the library of a major research university, and take an elevator to where they keep the history books. Prepare to be gobsmacked at the sheer size of it.

On my travels, I’ve stopped occasionally and briefly at Lewis and Clark historic sites, and, boy, there are a lot of them. Not a shock when you look at how far the Corps traveled. Of course, they never really had a clue where they were going. Going was their job: To find out. But hey, they had Sacagawea to show them the way, right? Not that she got credit, right?

Um, no. In a coming post, I’m going to show you why that’s nonsense. Sacagawea was as lost as L&C were. Which is not to say that she wasn’t important to the expedition, just not in the way we tend to think.

For today, let’s see how lost were Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea, and all the others in the Corps of Discovery as they crossed an alien (to them) land. And what happened on one occasion when things seemed desperate in their unfamiliar environment. And why it might matter in an age when people are starting to grasp historians' point that the past only makes sense when we stop making it all about a few famous men, and think about everyone’s perspectives. Of course, this is also a race against the forces of deliberate ignorance, who would rather we not know or talk about this. Ooh, don’t mean to sound like a conspiracy theorist: That isn’t a partisan comment either. It’s an observation about a tendency I have observed among privileged people who don’t think much of their supposed inferiors.

Annette’s Aside: Let Us Not Praise Famous Men

Biographies of “important” famous individuals (no, not just white men), rather than books focusing on people in broad context, have typically* fallen out of favor among US academic historians. Not because we’re being woke or whatever, but because we figured out that this isn’t often the best way to understand what’s going on. Early Americanists have led the way on this, I’m proud to say.

*UPDATE There are notable exceptions, especially bios of leaders we do need to hear more about, like David Blight’s terrific bio of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and Alison M. Parker’s awesome bio of women's suffragist and civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell.

I'm not saying this has always worked out well for historians’ popularity and public influence: We have farmed out most presidential bios and other narrowly-focused bios to popular historians (i.e. typically journalists), who make a lot of money writing stuff the public wants to read, because they like the comfort of thinking things about history they have thought since Mrs. Grabowski’s day.

Academic historians are generally focused on getting at what happened in the past, and why it matters. We (well, not me anymore since I became a renegade, and not the historians who have become wealthy media darlings) are most concerned with our reputation among historians. We don’t expect to become famous among the public.

At least, that’s the way it has been. I became a public historian years ago—so I write for the public. Now, with a massive jobs shortage, more scholars are turning to writing for the public . . . Or trying to. Ah, I have news for them: They had better love history so much, they're willing to starve for it, or else prepare to sell out. The only rich historians I’ve seen are cashing in on the public’s thirst for political commentary and predictions, and pushing hero worship. Just nope to that.

A Refuge at the Dismal Nitch

I wasn’t thinking of Lewis and Clark at all as Hoosen and I were driving along the northern bank of the estuary, the widest bit, of the Columbia River (I suggest having a map on your screen!) We couldn’t see the Pacific yet, but the width of the estuary suggested the ocean was straight ahead of us.

Actually, I didn’t care. I needed to find a loo.

And . . . A miracle! Lo and behold, here was a rest stop! A loo with a view! For my non-US readers, a rest stop is basically a public loo with parking, found on every freeway and many major roads. Here, unexpectedly, was a rest stop on the narrow road, crammed between estuary and cliffs. Yay! Phew!

Before hitting the road again, Hoosen and I paused to snap photos of the view:

I glanced at an info panel, which featured a map, with text urging me to plan to see a looooong list of places of interest in the immediate area, including Lewis and Clark-related sites. I didn’t even read the text, just swept my eyes across it, and took a photo.

Even if I were an L&C fangirl (I’m obviously not), we weren’t sticking around. We had somewhere to be! We were headed to the seaside hotel we had booked at a spectacularly low April rate in Seaside, Oregon, half an hour to the south of us, and the afternoon was wearing on.

Both of us were keen to get to Seaside, but especially the long-suffering Hoosen, he who gamely accompanies me to all sorts of museums. Hoosen loves loves LOVES the beaches of the Pacific Northwest.

No, not for Hoosen lazing beneath a palm tree on the warm sands of some tropical beach with a frosty drink, while azure waves lap gently at the shore!

No, Hoosen, bless him, wants to pop on a sweater, and stride purposefully down a rocky beach into the teeth of gale force winds and horizontal rain while massive dangerous waves crash onto shore!

No, much as I love him, I don’t get it either.

Anyway, Hoosen—ready for the beach!—and I were ready to cross the Columbia River on that bridge in the photo. By the time we crossed it, we would no longer be in Washington State. And no wonder we were in a hurry, eager, like L&C, to get on our way! Amazingly, the weather was cooperating in the notoriously rainy Pacific Northwest! We had an unseasonably warm day! Blue skies! Sunshine! Better get going!

An easy trip it would be. All we had to do was drive less than a mile, then turn left to cross the nearly four mile bridge to the small city of Astoria, Oregon. Then we would rush to get to Seaside on this unusually glorious day in the Pacific Northwest before the clouds come back! Sure, experiencing great crashy waves in the pouring rain worked for Hoosen, but this Brit loves a nice bit of sunshine.

Hang on. An unexpected development. Lewis and Clark had shown up at the rest stop to pester me.

“Excuse me, Dr. Laing?” Lewis (or was it Clark?) was saying. “How can you call yourself an early American historian and not be interested in us?”

“Watch me,” I said through gritted teeth. “Maybe I’ll find room for you one day, guys, but don’t bother pulling an attitude. My whole point at NBH is to show that we can’t understand American history by just focusing on a few high school history stars like you. So, enjoy the trip. Catch you later, maybe. Don’t call me. I’ll call you.”

I was not about to be guilt-tripped by tedious textbook prima donnas like Lewis and Bloody Clark.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see Sacagawea hoisting up her baby on her hip, and that gave me pause. Nope. Nope. I mean, what’s the point? We’re leaving. Heading south down the Oregon coast. Lewis and Clark looked disappointed. But they didn’t move. Just stood there. I swear that Clark (or was it Lewis?) tutted.

I looked again across the Columbia River. We must be near the Pacific, I thought, near the end of Lewis and Clark’s journey to the ocean at the end of the continent. Now I imagined the whole team, the Corps of Discovery, smoothly paddling west to the Pacific, their final destination, in canoes on the river in front of me. They were all set. They had a nice day for their journey. Blue skies! River flowing gently!

Well, whatever. I pretended not to see another info panel by the riverside. Everything was urging me back to the car. And then, as I passed the loo, I saw a map outside the building with a short bit of text above it. Of course I read it. What did the text say? This:

DISMAL NITCH

Pinned here against the rocky shore, the Lewis and Clark Expedition took shelter from the waves, strong winds, and torrential rains of a Pacific Northwest storm. It was the first time during the long journey that William Clark described the situation as "dangerous." They remained trapped here with little food and worn-out clothing from November 8-15, 1805.

Wait, this loo/car park was itself a Lewis and Clark historic site? My rest stop had been their rest stop, more than two hundred years ago?

Seriously? This loo with a view was a Lewis and Clark site?

William Clark, So Much Drama

Standing there on that sunny day, I realized the weather had not been nice, not for Lewis and Clark. I looked again at the calm river under blue skies, and tried to picture it under heavy imposing clouds, with violent rain and wind stirring up huge waves. I looked behind me, at the rocky, tree-covered cliff beyond the road. Yeah, good luck climbing that in a gale, and hoping to find shelter and food at the top.

Nope. L&C, their team, clothes falling apart, food supplies shrinking, and no real shelter, were now helplessly stuck in a tiny cove being lashed by wind and rain, in the worst moment of their entire journey. William Clark, the panel said, had never before called their situation “dangerous.” Wow.

It wasn’t rain and howling wind today. On this lovely day, we weren’t having to deal with rain, So, it really wasn’t a big deal to linger just another minute here, to take a moment and walk back and photo the info panel I had skipped, the one put there by the National Park Service.

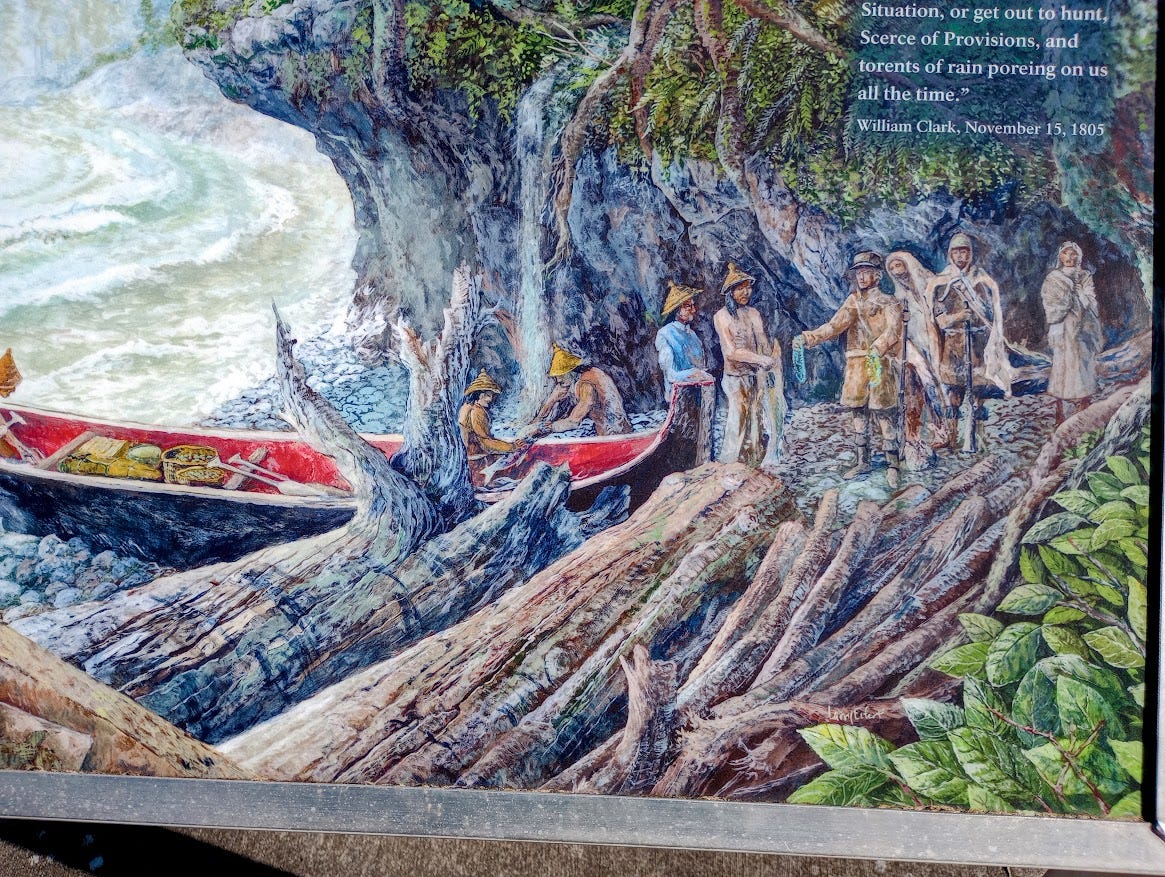

Here’s the painting from that info panel. A modern artist’s impression, and not a very good one. Some 19th century white guys in a tiny cove. meeting with Indians wearing the distinctive cedar hats of Natives in the Pacific Northwest. Lewis, or maybe Clark, or maybe someone else, offering the Indians what appeared to be a big condom, but I admitted to myself, was more likely supposed to be a fish. Which made no sense Huh.

Clark is quoted, with good old fashioned respect for spelling, meaning no respect at all.

"...This dismal nitch where we have been confined for 6 days passed, without the possibility of proceeding on, returning to a better Situation, or get out to hunt, Scerce of Provisions, and torents of rain poreing on us all the time."

—William Clark, November 15, 1805

Torrents of rain . . . Trapped . . Howling winds . . Everyone soaked to the skin . . . Clothes rotting . . Day after day after day . . . Everything feels like Death . . .

Suddenly, the National Parks Service-written text gleefully reports on the info panel, five well-dressed Native Cathlamet salespeople turn up in a canoe loaded with fish for sale. And then comes the event depicted in the picture.

I can just imagine the convo as the rainproof-hatted Indians clamber out of the canoe before the astonished eyes of L&C and the Corps.

“Hello, guys! How are you all today? Honestly, you look like drowned rats. Look, you’re new here, I see that, so me and my colleagues do regular rounds in this area, and we have some lovely fresh fish for you today, no cheap frozen stuff. What will you give me for these beauties?”

Okay, yeah, that didn’t happen. But it pretty much did, according to the info panel, just not in those words.

William Clark had for days been writing frantically in his journal of imminent doom in a disastrous storm that had not only driven the Corps’ canoes ashore, but stranded them all at this tiny cove, the “dismal nitch”. They were soaked, shivering in strong winds and rain, running out of food, cue the scary music. . .

Suddenly, these Native blokes calmly canoe in on their regular delivery rounds, sell L&C some fish, and then push off back into the Columbia River, no problem. Today, it might be a pizza delivery turning up when we are lost in the forest.

Lewis and Clark must have felt like a right pair of numpties. I would. I smiled to myself.

So did William Clark exaggerate the group’s plight? Was this all-American hero a bit overly dramatic? Did he feel a bit silly when Indians showed up, business as usual? I had no idea. But it was fun to think about.

With that, Hoosen and I boarded the NBHMobile, and within the minute, we were on that very long bridge heading across the Columbia River where once canoes had plied their trade routes. Halfway across, we passed from Washington into Oregon, on our way to Seaside, far from thoughts of Lewis and Clark and Sacagawea and fish deliveries to rocky refuges. For much of the way, a seagull flew alongside the car. Lovely. Outta here, all of us.

Not So Fast

As Hoosen drove, as we approached the city of Astoria at the bridge’s end, I was reading on my phone. I learned that we were near the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (UK readers: a museum at a place where something once happened.) Oh, well. Too late now.

But then Hoosen suggested that we visit the National Historical Park the next day. How can we do that, I protested? We’ll be in Seaside. He pointed out that we were only staying one night, and that it really wasn’t a long drive back here. He had a point.

And that’s how I ended up spending the very next day in the world of Lewis and Clark.

But writing about that next day would absolutely be too much for today's Road post. The Dismal Nitch is story enough.

Join Me Down The Historian’s Rabbit Hole

Still, as I started to write this post, I thought it would be interesting to see what else Clark wrote in his journal that day. Maybe I could check out the encounter with the fish guys in his own words, rather than rely on the National Park Service info panel. This is the problem with being a historian: We're trained never to stop being curious.

So I went to Clark’s journal. which is available online from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Big mistake. I was headed down a rabbit hole. As usual. I had to climb out fast or this post would never get done. But this, THIS is why history should never, ever be taught as it is in high schools and bad college classes for freshmen: Cut, dried, end of, one bloody thing after another, told in Cliff’s Notes format.

In academic history, there is no end to the digging and thinking and reading and writing. None. When we retire or die, we pass the burden to the next generation (and no, Artificial Intelligence CANNOT do this work). That’s because times change, and although the past remains the same, history is not the past. It's the interpretation of the past, and like language and fashion and everything, history changes. We keep reading the massive supply of old documents, re-reading and re-thinking books.

That's why we know, all of us historians, that the history we write will become obsolete, and we will be forgotten. Meanwhile, most of us never really retire until the computer mouse or the book is pried from our cold dead hands. I mean, I quit my tenured job more than fifteen years ago (because horrific corporatized good old boy institution in the Deep South, you can’t imagine). I can’t make a proper living doing history otherwise, and yet I never could let go of history. So, even though I no longer write history for a scholarly audience, I now write about history for you. And sometimes, at NBH, I dabble in writing history. Like now. I go to the primary sources, the documents…and dive in, head first.

And the more I dig, there's a danger I'll be lost to you, vanishing in some archive. . .

Aiee . . . 😱

Well, here’s what I found before I cried “Enough!” for the sake of this post not turning into a book. I found that while Clark’s quote on conditions in the Dismal Nitch was indeed from his November 15th, 1805 journal entry, the encounter in the painting between L&C and the visiting Indians didn’t happen on November 15.

No, I’m not going into a tizzy about “accuracy” in info panels. It’s absolutely no big deal. There’s only so much room on an info panel for explanations, as you can see. But this did mean that if I was going to read Clark’s version of the encounter with the fish salesmen, I now had to find out when the encounter did happen.

I sighed heavily. Oh, you wonder why NBH is my full-time bloody work, and not just some crap I knock out on my coffee break? There’s one hint.

So I skim-read backward, and found the incident four days earlier, on November 11th, 1805. That was about halfway through the Corps of Discovery’s soggy, scary ordeal, trapped at the rest stop. Not that they knew they were halfway through their ordeal. Not to say that they weren’t already soaked, shivering, hungry, and frightened.

But here’s what happened, according to Clark. I’m going to jump in and tidy up/lightly translate Clark’s words for you to save you time, but the original is right here if you want to see it.

At 12 noon, the wind was very high and waves tremendous. Five Indians came down in a canoe loaded with fish of the salmon species, called Red Char. We purchased from those Indians thirteen of these fish, for which we gave them fishing hooks and some little cheap trinkets [cool imported stuff in exchange for a few boring fish— A.].

We had seen those Indians at a village behind some marshy islands a few days ago. They are on their way to trade those fish with white people which, they signed, live below round a point. Those people [the Indians, I assume, not the white guys nearby—A] are badly dressed.* One is dressed in an old sailor’s jacket and trousers, the others in elk skin robes.

*Says William Clark, the man dressed in soggy and rotting buckskins . . . —A.

Clark now carries on whining about his misery. Yet —look—he also expresses reluctant amazement at the Indians’ boating skills:

We are truly unfortunate to be compelled to lie four days nearly in the same place at a time that our days are precious to us. The wind shifted . . . the Indians left us, and crossed the river which is about five miles wide through the highest seas I ever saw a small vessel ride. Their canoe is small. Many times they were out of sight [hidden behind waves—A.] before they were two miles away. Certain it is they are the best canoe navigators I ever saw.”

Well, the local Native people were much better navigators than you, Lewis and Clark!

So, despite the romantic Thanksgiving overtones of the encounter, of Americans and Natives trading in peace, the story of magic Indians coming to the rescue of grateful white guys (think e.g. Pocahontas and John Smith), it’s clear that what is going on is complicated, that a dramatic episode featuring brave adventurers is actually just an ordinary day of catching and selling fish in crappy weather for the locals, as they have been doing for hundreds, thousands of years. And that the account is heavily tinged with Clark’s smug, unearned superiority, like I hear from Americans who think they know Scotland better than Scots, when they've just come for a week to pretend they're Scottish. Oh, did I say that aloud? Oops. Hey, if it makes you feel better, I think I did that to Canada when I was there last month. Oops.

So let’s skip forward once again to November 15, the day that Lewis and Clark decide to finally leave the “Dismal Nitch”, the rest stop where they have been camping, too inept as oarsmen to move, while Indians zip handily back and forth across the Columbia River in full view of their resentful visitors.

On this last day, Clark wrote,

“Four Indians in a canoe came down with papto roots [no clue—potatoes? A.] to sell, for which they asked blankets or robes, both of which we could not spare. I informed those Indians, all of which understood some English, that if they stole our guns, etc, the men would certainly shoot them.”

Lewis and Clark, United States diplomats, making friends and influencing their way across America! In fairness, it seems that Natives may have pinched a couple of guns while the Corps slept in the rain, but, as I have learned, the Corps wasn’t above helping themselves to Native people’s canoes. Just saying.

Wouldn’t it be great to have a Native account of these encounters? Ooh, if that exists, I’m on it. But not today. Time’s up. And if you think I went on and on and on? Welcome to history. This is why historians don’t get invited to parties. If we could get away with it, we would never, ever shut up.

Instead, we pour our thoughts into massive long books, stashed away in university libraries, in an age when we’re about to outsource thinking to machines that, really, truly, cannot think like this.

P.S. Bite me, Artificial Intelligence (AI), the College of Ed numpties who (asusual) jumped mindlessly on your bandwagon, and the scammers who are selling you. Readers, if you think computers are trustworthy, watch Mr. Bates and the Post Office on PBS (watch it anyway), the story of how thousands of decent British people had their lives ruined by faulty software led by the same lazy greedy ignorant cretins who are ruining everything.

And consider that after Amazon closed its food stores in which you could grab the food and leave without paying, it emerged that the hi-tech checkout system was actually thousands of desperately underpaid people in India, watching from cameras.

Meet NBH SuperNonnie Caroline Ross!

Caroline is a SuperNonnie, a founding patron of NBH, and (since she lets the cat out of the bag) a former student of mine at Georgia Southern University. :)

About Caroline:

I had the pleasure to be in Dr. Laing’s Public History class when she was teaching, and I’ve been following her work since then. I currently work as a Client Service Representative at an accredited service dog organization in Virginia.

When did you get interested in history, and why?

I think I’ve always been interested in history. I actually can’t remember a time I wasn’t. My father played a big role in this. His passion for history was passed onto me through renovating old houses, repairing antique family furniture, talking about family history, and visiting museums (which I’ll admit as a child weren’t also appreciated.) My high school history teacher also played a big role. Instead of regurgitating facts and dates, my teacher encouraged me to look at past events to see how it shaped my present and to think critically and not accept something at face value.

Why do you enjoy and support NBH?

I loved the way Dr. Laing engaged with us as students and challenged us. In her class I was being taught, not being lectured at. By being a Nonnie I can still continue to learn with Dr. Laing without having to worry about finding a parking space. By supporting NBH, I can travel vicariously with her learning about a variety of subjects. I also can share this with my son in hopes that one day he too will share my passion of learning new things through history.

Join Caroline as an NBH SuperNonnie, and be a founder! Details here: